Tracy McGrady has a sprawling estate hidden away somewhere in Texas. The drive to it leaves city skyscrapers far behind in rearview mirrors. The drive to it presents signs to be careful of passing deer. The drive to it goes through grass flatlands.

Today’s Texas sun is becoming increasingly unobstructed on the trip to Mac’s spot. On the roll, with the wind blowing through and the rental car’s engine roaring, the Texas sun is most definitely keeping the warmth. Early January doesn’t feel like early January.

Cerulean and cloudless above.

Slow and steady pace.

More ease than worry.

Not late.

Not early.

Right…on…time.

Then it appears, a huge spot where one of the game’s most unstoppable individual talents lays his head.

Black gates keep Mac’s home safe. There’s no answer to the exterior intercom’s inquiry, but the gates open sesame. They don’t reveal 40 thieves like in the famous tale. Instead, Mac suddenly appears just to the left of the front door of the main house. Calm as always. His pace is slow and steady, with more ease than worry. His hands are in the pockets of his personalized black adidas sweatpants, which he’s styled to rest stationary above his white adidas socks, which then lead down to a pair of adidas Forum Lows that shine and sparkle with their first wear.

He introduces himself with all the reserved yet knowing energy of the coolest kid in high school.

He was that. Still is.

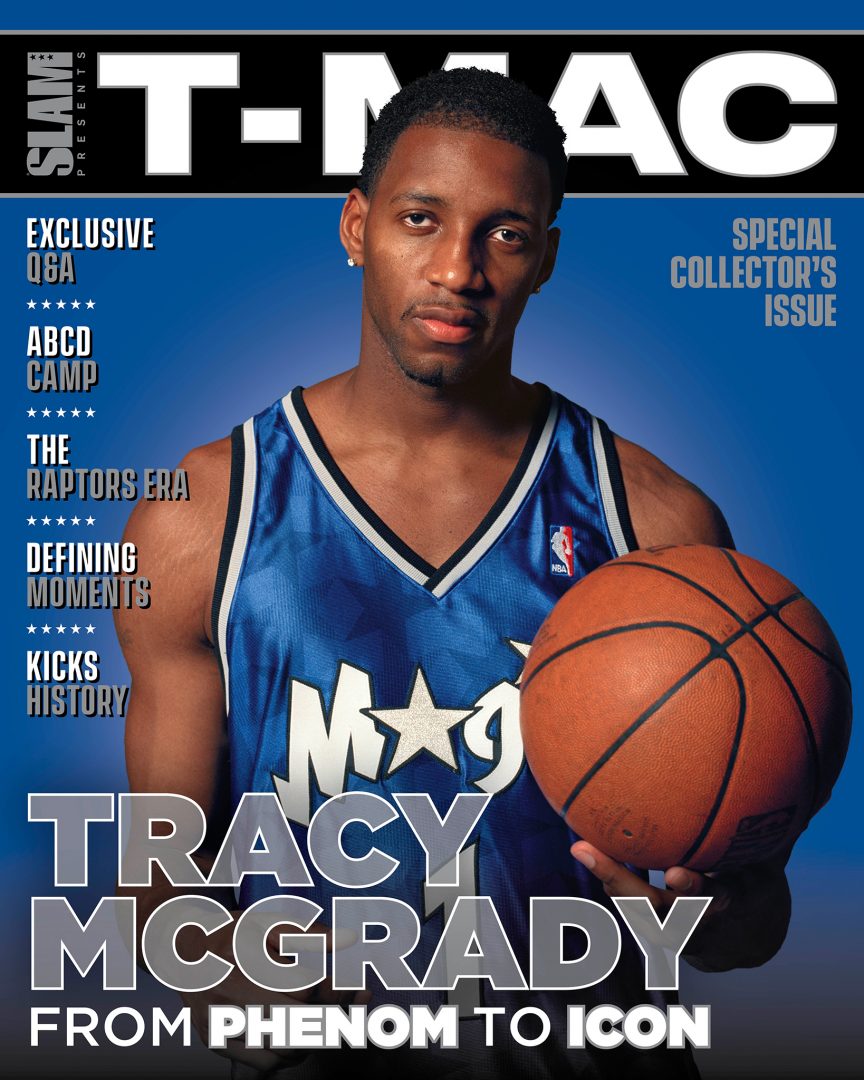

An entire special issue dedicated to T-Mac’s unmatched creativity.

It takes just a beat for Mac to turn and saunter over off to the side of the main house. The Texas sun that was coming out to play during the drive is dropping out of sight behind the tall building that we’re being led to. Sturdy double doors open, Mac hits a light switch and it all comes to life. An NBA-sized court is the star, flanked by a weight room to the right and a kitchen, along with a hallway that leads to an office and a separate room with a barber’s chair, to the left. Moving at this slow and steady pace allows for more to be seen. So when the light flicks on, it’s cinematic, and all that’s missing is a rising orchestral piece to accentuate the grandeur of the one and only T-Mac Arena.

But, if that music were to be playing, it’d make it more difficult to hear all the late-night swishes that have rang out in here, or all the weights that have clanked together, or all the times that his signature adidas sneakers have squeaked against the hardwood. There are ghosts in this building. Not bad, scary ghosts, but rather the ghosts of T-Mac’s greatness as an NBA player. Ghosts of T-Mac helping the local youth who get to come into this gym and learn from one of the coldest to ever play. To see everything that’s here, but not here at the same time, is an exercise in thinking like Mac, in imagining like Mac. He’s one of the few whose claim of changing the game isn’t just a claim—he did things on the court that nobody had seen before. As a ballplayer, he was a mind-opening inspiration, someone who laughed at previously-perceived boundaries on his way to breaking new ground, or, most often, soaring to new heights.

The rims in the Arena are soft and forgiving, and their nets offer a serenade when swishes sustain enough to stick in the soul. Treasures, both physical and otherwise, wait here.

Some of those treasures sit just to the right of the main entrance in the form of a duffle bag overflowing with T-Macs made just for T-Mac. They’re all adorned with the “sample” tag, in his size 16, and they range from 1s to 2s to 3s to Millenniums. Black paint runs the length of the baseline underneath the duffy. “T-Mac Arena” is stenciled in big italics, joined by solid black italics on both sides of the floor, near the half court line, that read “HOF17.” Self-explanatory. The court itself is bouncy under-foot and accented by all the goodies that any ballplayer could ever want. Shooting guns, d-fenders and medicine balls dot the sidelines. A giant T-Mac logo is at halfcourt, directly underneath the highest point of the A-framed building, where the white ceiling slopes all the way up before coming back down again.

Mac gets the music going on the loudspeakers and we hear Hov, Jada and a bunch of others while he poses with his kicks in celebration of being Striped out for 25 years.

Before time feels like time, it turns out that nearly four hours have passed us by. We got lost in conversation and in photo shoots and in the confirmations of stories that have long been rumored (the game at Rucker Park on August 14, 2003 would have been the best ever, if not for that blackout). See, what happened was we time traveled, melded the past, present and future, and forgot about the Texas sun. It had gone from high in the sky to closer to the earth. Slow and steady pace.

The first stop we made was high school, back to Mount Zion Christian Academy, back when he did something he would become famous for.

“I always wanted to be creative,” Mac says. “You know, I’m a creative thinker, and I want to be the first to do something. I want to do something that nobody’s done, especially on the NBA level. And when I was in high school, a team was playing a 2-3 zone, and I just got tired of the two guys [at the top] stopping me from penetrating to the basket. So I got pissed and I said, I’m gonna split these two dudes, I’m gonna throw it off the glass and I’m gonna catch this off the glass and dunk it.”

He pauses for just a moment to grin.

“So when I get to the NBA, I wanna throw it off the glass against the best players in the world,” he continues. “I would love to do that. I’ve never seen this in an NBA game, right? Never seen this. We’re in Boston, preseason. Score is 2-0, us. Ball coming down. Kenny Anderson, Paul Pierce, right there. Throw it up. I come out of nowhere. Bahhhh.”

He mimics the throwdown with the animation in his voice sounding like he’s wrapped in the moment all over again.

“Preseason,” he goes on. “I see my teammates Troy Hudson, Pat Garrity, all of them going crazy. Man, wouldn’t that be dope to do that at the All-Star Game with all the best players, with all the celebrities? Philadelphia. So to do this, right, you got to have supreme confidence within your ability. At this point in 2003, I feel like nobody can touch me. In 2002 to 2003, feel like nobody can touch me at this time. I’m highly skilled, I’m confident. I feel great. I’m quick, fast, like, I am at my best. We’re at All-Star Weekend. Jermaine O’Neal gives me the ball coming down on the left side. I see Dirk [Nowitzki] standing right there, I see GP [Gary Payton]. Got the ball in the left hand. Left hand coming around. Everybody do this. Just come out of nowhere. Boom. Boom. Go crazy, everybody go crazy, it was legendary. And I’m like, That’s the moment I’ve been waiting on. Because that, what I just did, I know that’s going to be around for years, for decades. Right? So I was the first one to do that. And that was the creative mind that I had. I just wanted to try different stuff, man. Why not? I worked too hard, bro. I put in a lot of work. You know, waking up 5 in the morning, three workouts a day. I put that in, you know what I’m saying? And that gave me the utmost confidence to be able to try anything on the basketball court because I believed in my ability and I wasn’t afraid to do that.”

There seemed to be two different versions of McGrady on the court. There was the calmer guy, the one who would accept double-teams and snap crisp cross-court passes to the open man. Then there was the superpower version. That version was able to easily traverse the unseen and narrow bridge between knowing and flowing. That’s a bridge where all the conscious years of skills training, physical training and mental training lead to a disconnection from all of that intention and into a state of complete instinctual expression. Off-the-board tosses and 62-point outbursts and the otherworldly 13 points in 33 seconds, for example.

And while Mac confirms that there were moments where he slowed down as an individual to get touches for his teammates, he says that he was never disconnected from his mind or body. It was the opposite.

“I’m aware. I’m aware,” he says again for emphasis about those moments that look like unfiltered genius. “When I could tell one of my teammates ahead of time, Yo, I’m about to throw this off the glass, bro. Chris Whitney, when we was playing against Toronto in Orlando, Chris, watch this, I’m about to throw this off the glass. I know how the flow of the game is going, right? I know there’s nobody out here that can touch me on this basketball court, right? And the moment’s going to present itself. I know it, right? I’ve played too many games, I worked too hard to get that feeling, right? To get that feeling and to be that confident. When you got control, when you know you in control, just play ball, man, and the defense will be at your mercy. I think when you are solely confident in your ability and you know the temperature of the game, the Florida game, when you’re highly skilled, you can pull these things off. That’s all it was. I just, I knew I could go behind my back because when you create this persona, guys know us. It’s real. Guys know you’re the shit. They know this is T-Mac they’re guarding. I’m not saying this is everybody, but some of the guys that are guarding you, you can tell they’re a little timid. That’s what I mean, I’ve got control of the situation because I know these guys [and] they know there’s nothing that they can do with me.”

He credits all that to waking up before the daylight would wash over Toronto, Orlando, Houston and everywhere else he played. It looked easy because it wasn’t. He acknowledges that there was a lot of natural ability at his disposal, but he also emphasizes, multiple times, that he worked as hard as he could.

There’s this thing that keeps happening with Mac during all this time traveling. His body language and the cadence of his voice keep on illustrating how much this all means to him. Those same hands that used to shoot from anywhere or fling passes from his hip are waving throughout the air. He’s using them as instruments to further add to all the life in his spirited speech. Given the space and time to speak and reminisce, he’s an artist sharing the secrets of his craft. And given that we’re in the physical space of T-Mac Arena, his artist studio as it were, he seems to be somewhere in between then and now, physically sitting in a chair at his home while spiritually floating through memories.

What that craft did was expand the minds of all the kids who watched him. He introduced possibilities, thought to be just fantasies, into reality. There aren’t many who have been able to accomplish that.

SLAM Presents T-MAC is OUT NOW! Shop here.

McGrady even surprised himself. He points out the behind-the-back dribble move against Shaun Livingston (salute to the three-time champ) from the left post. It was 2006. Out of that move came a fadeaway to the baseline. The shot lofted into a net-ringing swish. Hall of Famer Clyde Drexler was on the mic for the broadcast. He used the word “creativity” in his astonished call of the moment.

It’s just a snapshot of the brilliance. The snapshots add up to make the mosaic that adidas, all the way back in 1997, was aware would one day be painted.

This marks the 25th year of the Tracy McGrady and adidas relationship. It’s rare air for one player to be with one brand for that amount of time.

“It’s unheard of,” Mac says of the longevity. “I think Mike [Jordan] and AI [Allen Iverson] are the only ones that are still doing that at this rate. It’s because of that reason, because we built something that is still relevant to today. When you announced some T-Macs are coming out, they’re still selling out. Why go anywhere else? We’re still doing good things. And you got to understand, I’m still one of the only guys that is selling shoes 25 years later. It’s not many. It’s not many. And I’m talking about guys [in] my era that was superstars. I’m one of those guys that are fortunate enough to still be doing it. So you gotta keep going.”

The line has kept going with the recently released T-Mac Millennium 1s and 2s. The Stripes have retroed his line with the Restomod versions of the 1s, 2s and 3s. That’s where it stands today, after 25 long years. But how did the line start?

“I knew in my third season with adidas that I was going to be a signature guy,” Mac remembers. “Through conversations, through my play and how I was making a name for myself. People saw the talent and the skill level and having that coming out party against New York in the playoffs, where, first game I think I had 25, 26 points in my first-ever playoffs [It was 25 at MSG against the Knicks.—Ed]. And I averaged, like, 16 [points per game] that whole playoff series against a tough Knicks team. I knew I was going to get it, it was just a matter of time. And God bless, he did. My brother Kobe turned down adidas. Kobe was about to sign a $200 million deal with adidas. Who was next in line? I was like, Kob, thank you, brother, thank you, brother. I’m glad you turned down that $200 million because you left me a $100 million, bro!”

T-Mac ended up being the sole face of adidas Basketball throughout the early and mid-2000s. The Stripes didn’t push out other designers alongside of him and they made him the star of some amazing and memorable commercials. He says there wasn’t a discussion about that. It was just natural. He was in the moment and that moment called for him to be the Stripes’ star.

Like everything he did, from his sneakers to his scoring, No. 1 was No. 1.

But it’s not like Mac is done accomplishing. The Ones Basketball League will be touring the country this summer, bringing his idea of a one-on-one league to life. He also just started a sports agency with six-time All-Star Jermaine O’Neal. And as we start to wrap up our shoot for the day, a team of elementary school-aged kids start to file into T-Mac Arena. They work on form shooting and ballhandling. Even at that young age, they’re learning the fundamentals. They’ll be next in line, at some point, after the current crop of high school sophomores that Mac has been mentoring through his AAU program. That group of 10th graders, Mac says, has been with him for six or seven years.

“I put in a lot of effort, energy, money behind the youth,” he goes on. “I don’t broadcast that, I don’t show that off a lot. But it’s what I do because I want these kids to win. I know how tough it is to make it and what they’re trying to accomplish. But it’s my job to really give them the tools and information so they can be successful and help them understand that if basketball doesn’t work out, it’s OK, you can win at other things. It’s not everything. There is life for us. We would love to make it to the mountaintop, but when you got an AAU program, maybe one or two of those guys make it. What about the other guys? Like, what are you instilling in them to keep them confident? And I think for me that’s what I really thrive on, is building up the confidence of the kids so when they leave my program and leave me, they’re extremely confident and they know where they’re going, they know the journey that they’re on. And if basketball doesn’t work out for them, there’s still this confidence to feel like they could be successful in life because I gave them the tools in life to be successful.”

That’s the last thing Mac says before standing up out of his chair and walking across the bouncy hardwood floor of the Arena. He’s left the treasures of his sneakers behind him. The patent leather of the 2s and the faux croc skin of the 3s are the ghosts of the past in the present. There’s also the treasures of everything he just said and didn’t say. The ghosts of the future for the kids reading this somewhere who got to see the love and care for craft, the pride in passion, even the way that the old can be experienced anew.

He exits through those sturdy double doors, revealing that the Texas sun has become the Texas moon. It’s glowing high above a sprawling estate hidden away, where deer roam across guarded grass flatlands that lay behind black gates.

Portraits Jon Lopez, action photo via Getty Images.