This story appears in KICKS 25. Shop now.

Way up in Oregon, raindrops fall through big branches of cedars, maples and firs, blanketing their vivid green leaves in layers of water. See, the Gulf of Alaska brings in low pressure systems to the Oregon coast, mixing it along with moist air from the Pacific Ocean. By the time it all hits Oregon’s mountain ranges, it settles as big, gray clouds and heavy showers.

Storms as the main character of an entire region can be gloomy for the uninitiated. The flip side, though, is rain’s renewal. After all other audio distractions fade, the landscape provides alternating tempos, sometimes emphatically pounding against car roofs, sometimes gently tapping the sidewalks. But no matter the natural soundtrack, the water washes away the old and leaves room for the new.

Away from the blistering noise of Portland, among the rain’s starring role, there’s been another sound. Pencils have been moving ferociously against stacks and stacks of paper for more than 30 years. Tinker Hatfield has been up here for all this time, sketching, sketching, sketching.

Thinking. Dreaming. Trying. Failing. Thinking. Trying. Trying. Trying.

Succeeding.

Hatfield has been the designer who has made the basketball world spin since the late 1980s. His ideas have traveled from the rain-ridden Pacific Northwest to the Windy City to Tokyo. His triumphant career can of course be credited to, in part, working with Michael Jordan on the Air Jordan III-XV and a smattering of others later in the line, the Air Jordan XX probably among the most notable. But to write off Hatfield’s legacy as only being connected to Mike is a disservice to the tinkerer.

A pair of other factors are at play here. His mind and his eyes work together uniquely. What he sees when looking at a building is completely different than what an everyday human would see when looking at the same structure. He sees dimensions that those on the ground can’t comprehend. His capacity for observation, and then processing, functions at a higher level. And he has no interest in staying stagnant. He is the renewal.

The Nike Air Max 1 and the Air Jordan III, his first two projects as a footwear designer in Beaverton, scared his coworkers so much that people wanted him fired. Exposed Nike Air bubbles and elephant print were too radical.

Phil Knight didn’t fire him, though, and Hatfield has been observing, processing and creating ever since.

So the obvious question to the man who has found solace in the scary for coming up on 40 years is:

How has he trained his mind to break beyond the limitations that most people can’t let go of?

Hatfield, in general, is modest. Conversations with him would give no clues to the fact that the entirety of modern basketball footwear can be traced back to his notebooks. The reservation in his answer says just as much as the actual words.

“Yeah, that’s a great question,” he begins, measuring what’s to follow. “I’m not sure there’s a point to point to point to point process,” he continues, with more measuring. “But I do believe that you have to think about, well, what’s really happening when you’re designing something?”

Now he’s found it.

“I think that it’s a culmination. I think to design or to do art, it’s kind of a culmination. It’s a culmination of everything that you’ve seen and done and experienced in your life up to that point. That’s really what really good design and really good art is, an expression coming from someone. And hopefully in the case of Nike products, there’s a performance about the whole thing which helps somebody achieve their goals. So that’s kind of how I think about, you know, where my heart lives and how I’ve used kind of that sense about product performance and also even fashion and style. Just sort of have a fairly smooth connection to all of those things.”

He uses the word “culmination” three times. Referencing a building in the example of how Hatfield’s mind works differently wasn’t random. The Air Max 1, one of the most legendary sneakers ever, was directly inspired by a building. A mid-’80s trip to the Centre Pompidou in Paris gave Hatfield the spark to expose the Nike Air bubble on the AM1. The idea clicked when he saw how the Centre Pompidou’s lead architects, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, exposed the interior piping of the building. The AM1 was the culmination of everything that Hatfield had seen up to that point.

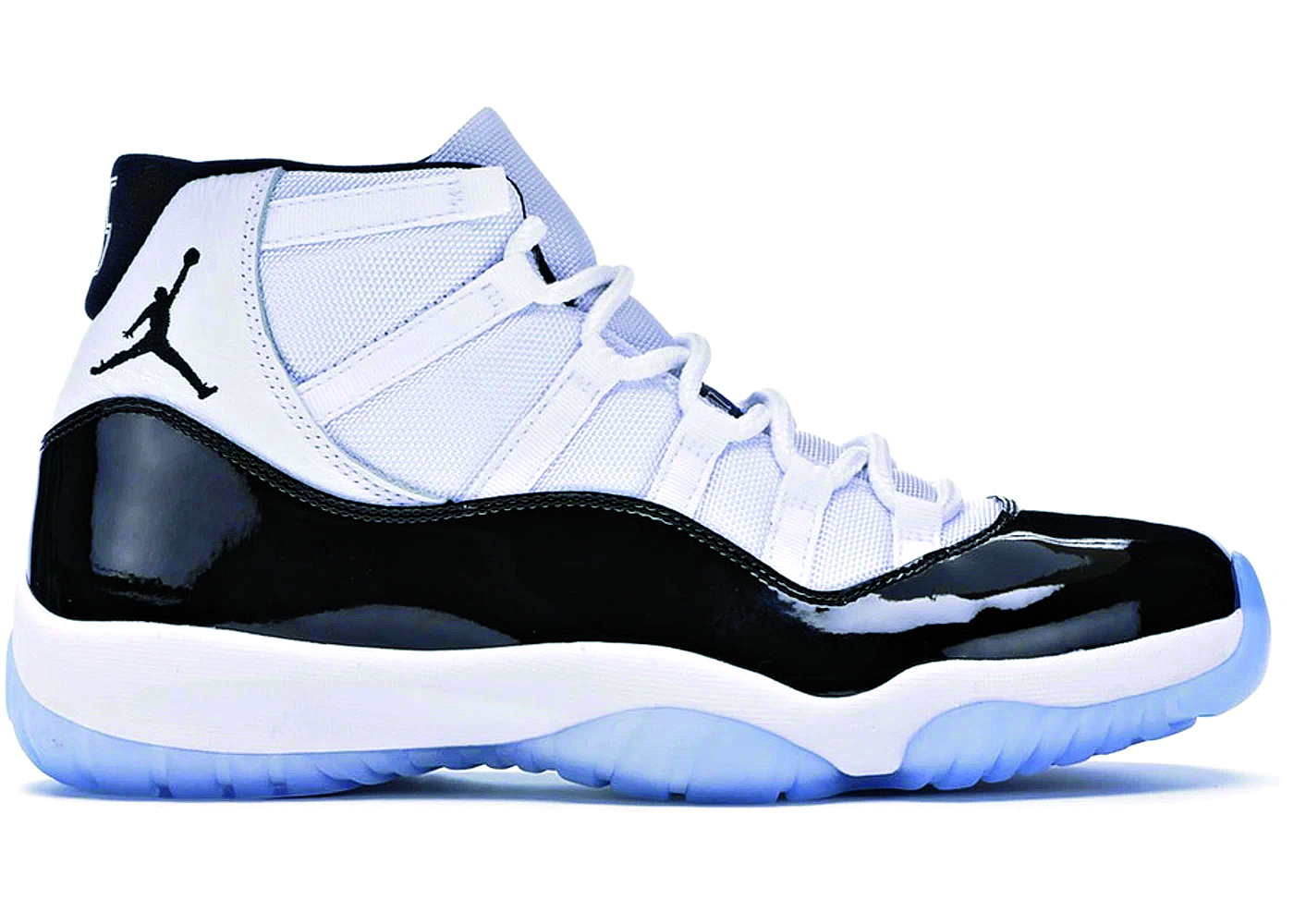

As was the Air Jordan XI, the Air Tech Challenge, the Air Mowabb, the Air Huarache, the Air Max 180, the Air Trainer SC, the Air Trainer 1, the Nike MAG and so many other silhouettes that Hatfield has crafted over the years.

Included in those pairs are kicks made for hoops, running, training, tennis, hiking and walking around. Hatfield says that even among all of those different fields of function, there’s a similar sensation he begins to feel when he knows he’s on the right path.

“I’m really critical when I draw something,” he says. “But I know within a few minutes if it’s the right direction. I mean, it’s very, maybe, bombastic of me to talk about it like that. But I guess I had the right kind of background to kind of do this job.”

He laughs almost nervously at the end, right after saying it’s bombastic to speak about himself like that. There goes that modesty again, like he doesn’t want the world to know how many rainy days and nights he’s spent in the studio, listening to the water coming down, both calmly and forcefully.

The background he mentions is very well known by now. Hatfield was a high-level athlete in his younger days, a star in track and field and a monster in pole vaulting. During his time at the University of Oregon, his coach (though he hated to be called coach) was Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman. Bill would have young Tinker test track spikes and report his findings.

“I learned a lot from those experiences because I was a wear-tester,” Hatfield says. “I was always trying some crazy new shoes that he had come up with. And I was one of the preferred wear-testers because I could draw some suggestions. But anyway, that was all good, good training for me. Just basically not just do the work, but also just have a natural feel. And I think that natural feel maybe comes from just being curious and out and about a lot.”

When he was effectively told by Nike brass that they were converting his role from corporate architect to sneaker designer, all that time and all of his natural feel caught up to his opportunity. His output was machine-like, but his designs were extraordinary, something only a special human could create.

The more he did, the more he learned. And even though the feeling he got when he knew he had something was consistent, the actual physical motions his right hand made while drawing varied from project to project, whether the moment called for footwear, apparel, architecture or something else. The studying he’s done of his own process is another window into the distance he created long ago from any other peers. Even with modesty in his voice, he answers the question about how his hands move differently without any hesitation. An observation he’s already made.

“Depending on the nature of the design and possibly the performance of a shoe, it could be a bit thicker and blockier,” Hatfield says. “And it could be maybe more mechanical, but not necessarily in a bad way. But it’s just different than, say, the very simple flowing lines that we do a lot. And so some understanding of the performance has to sort of fit in. But the reality is, once you have established this direction in your brain about whether or not it’s going to be kind of chunky and more masculine and powerful, or maybe it’s going to be sleek, slender, beautiful, you can draw differently to it to help sell that idea. So I can be real loose and just, you know, kind of, like, tail it off and it looks like it’s blowing in the wind, or I can make something look more mechanical and more, like, [robotic], if you will. So that’s a part of, I guess, a communication strategy, you know, to try to get across what was in your brain all along.”

Hatfield used to be in the public eye with regularity. His relationship with Mike and many other world-class athletes meant that he was Nike’s voice for the biggest moments in sports. Recent years have seen him take a step back into the storms of Oregon. He’s still active up there, even at 70 years old, surfing or skating when the weather allows it.

He’s become a sneakerized Yoda, keeping secrets of the craft earned through decades up there in the silence of his solitude. But he’s not holding on to those secrets. He hands them out to the seekers, to those who understand that without his brilliant combination of art, science, engineering and dreaming, a magazine like KICKS wouldn’t exist and neither would the current fascination with athletic footwear.

He’s not done yet, either. The showers will continue to fall way up there in Oregon, continue to wash away the old and make room for the new, for the kind of new that scares people. There will be more coming from his pencils among the pouring rain.

“You know, I find that there’s just no limit to how easy it is to scare people,” he says with a big laugh. He says that because he’s noticed people becoming more nervous in general, the artistic process can add to those feelings.

Before he goes back to the silence of the storms, he offers one last thought.

“A lot of what we do in general, maybe [SLAM does] it with a written word and I do it with a picture, but we’re telling stories in very nuanced ways or very large and impactful ways.”

Photos via Getty Images and courtesy of Nike.