Led by Guest Editor Carmelo Anthony, SLAM’s new magazine (below) focuses on social justice and activism as seen through the lens of basketball. 100 percent of proceeds will be donated to the Social Change Fund. Grab your copy here.

—

Words by Kazeem Famuyide / Portraits by Johnny Lewis

With heavy congestion on the New Jersey Turnpike, there was no need for speed. Keshon Moore, a point guard, known for always being aware of his surroundings, noticed a police cruiser ahead of him as he drove in the middle lane with his friend Danny Reyes riding shotgun. Jarmaine Grant and Rayshawn Brown, two friends of Moore’s, had fallen asleep in the back. The police cruiser slowed until it was nearly parallel to the minivan, making its presence unavoidable. The two white officers in the cop car looked over at Moore and Reyes as they drove alongside the van.

The cruiser pulled behind the van. Red and blue lights turned on.

Moore brought the car to a stop on the shoulder. As he began to slowly reach for his wallet, his foot came off of the brake and the car started slowly moving backward toward the front of the police cruiser—he had unknowingly put the van in “reverse” instead of “park.” The two troopers ran up and immediately broke the windows of the rented van with their batons.

And then they started shooting.

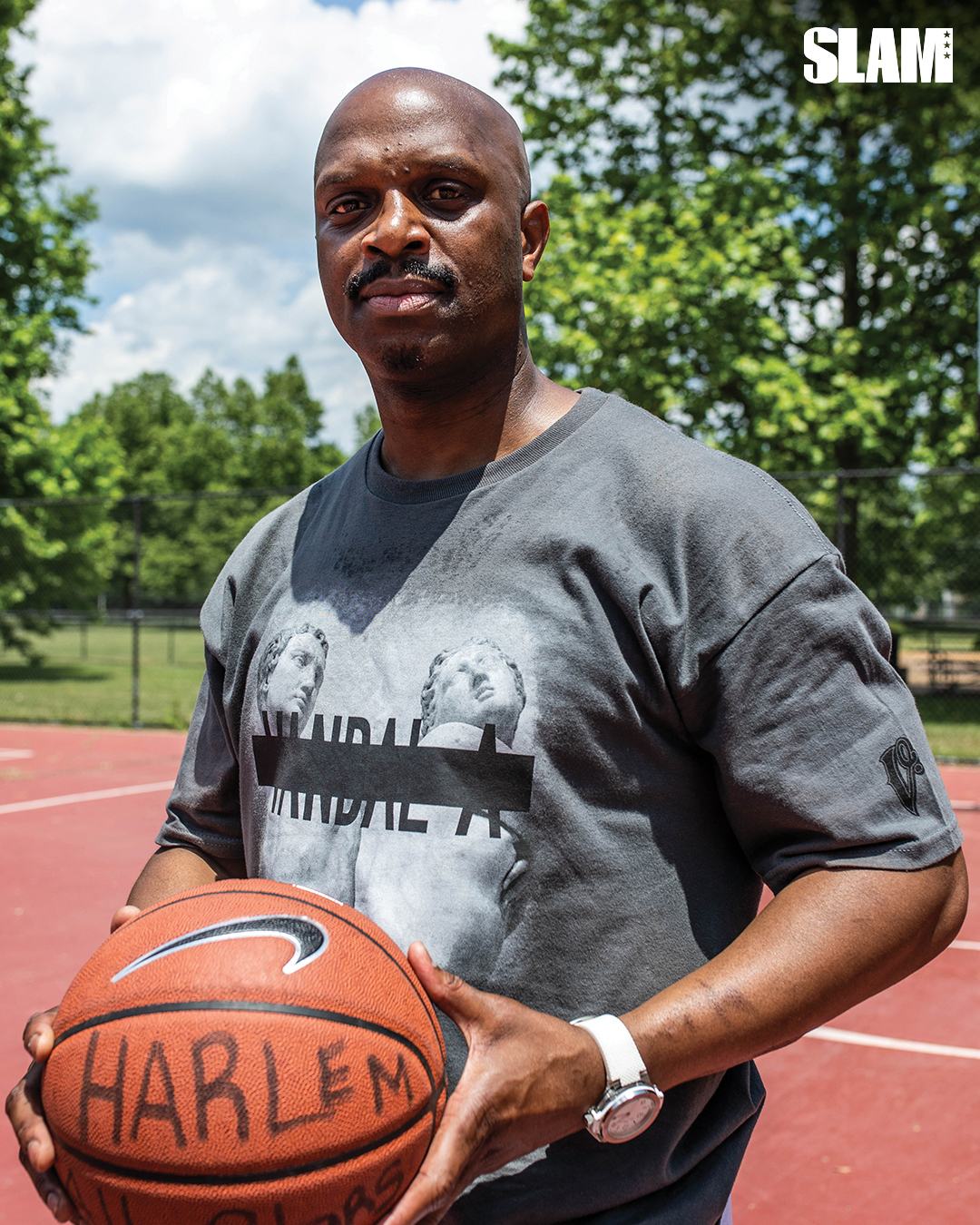

REYES & MOORE

There was always something special about a Curtis vs St. Peter’s matchup. About a 12-hour drive away in North Carolina was the true greatest rivalry in basketball—Duke vs North Carolina—and this was Staten Island’s version.

“That Curtis-St. Peter’s game was the first time I played against Danny [Reyes],” says Keshon Moore, who played for Curtis High School in the early ’90s. “There were like 2,000 people there, and it was a JV game. It was beyond what I even expected.”

“I remember because I hit the winning shot,” the 6-7 Reyes, who played for the Eagles as a freshman, says. “And those are the facts!”

Reyes would transfer from Peter’s to Curtis the following season and Moore’s playmaking abilities assured that success would continue, as the two went on to win the 1994 Staten Island High School League Tournament.

GRANT

Up in Harlem, a young Jarmaine Grant carried himself as a self-proclaimed “knucklehead.” “I wasn’t a future jailbird. [But] I was always in mischief,” Grant says.

A fight in seventh grade and a trip to the principal’s office changed his life course forever.

“As I’m sitting in the principal’s office, I saw some guy walk in and he’s kind of looking me up and down, and me being the knucklehead I am, I look back at him like, What is he looking at?” Grant says. “The man asked me straight up, ‘Do you like basketball?’ and I remember vividly saying, ‘Man, fuck basketball. I don’t care about sports.’”

The principal beckoned to the man trying to get Grant’s attention and said that the kid was basically a lost cause. Don’t even waste your time. He was done with that school.

But the man—a former pro and all-around legend named Nate “Tiny” Archibald—refused to take no for an answer.

“‘Why don’t you want to play basketball? You’ve got the height and you’ve got the frame,’” Jarmaine recalls Tiny asking him after he pulled him out of the principal’s office and into the gym. “Growing up in Harlem, I never knew the history of basketball there. I was the tallest out of my friends, but whenever I played ball [with them], I was just the stretch dummy.”

When you’re relegated to being target practice for the many rim-attackers that New York City produces, an NBA Hall of Famer handing you a basketball can be a form of divine intervention.

“If you want to know what this basketball can do for you, meet me here tomorrow morning,” the Bronx OG said to Grant before taking him back to his classroom. Grant bailed on a fight that was supposed to happen after school. His interest was piqued.

Under Tiny’s watch, Grant’s game began to blossom. He was a talented scorer who eventually enrolled at the legendary Rice High School in Harlem, NY.

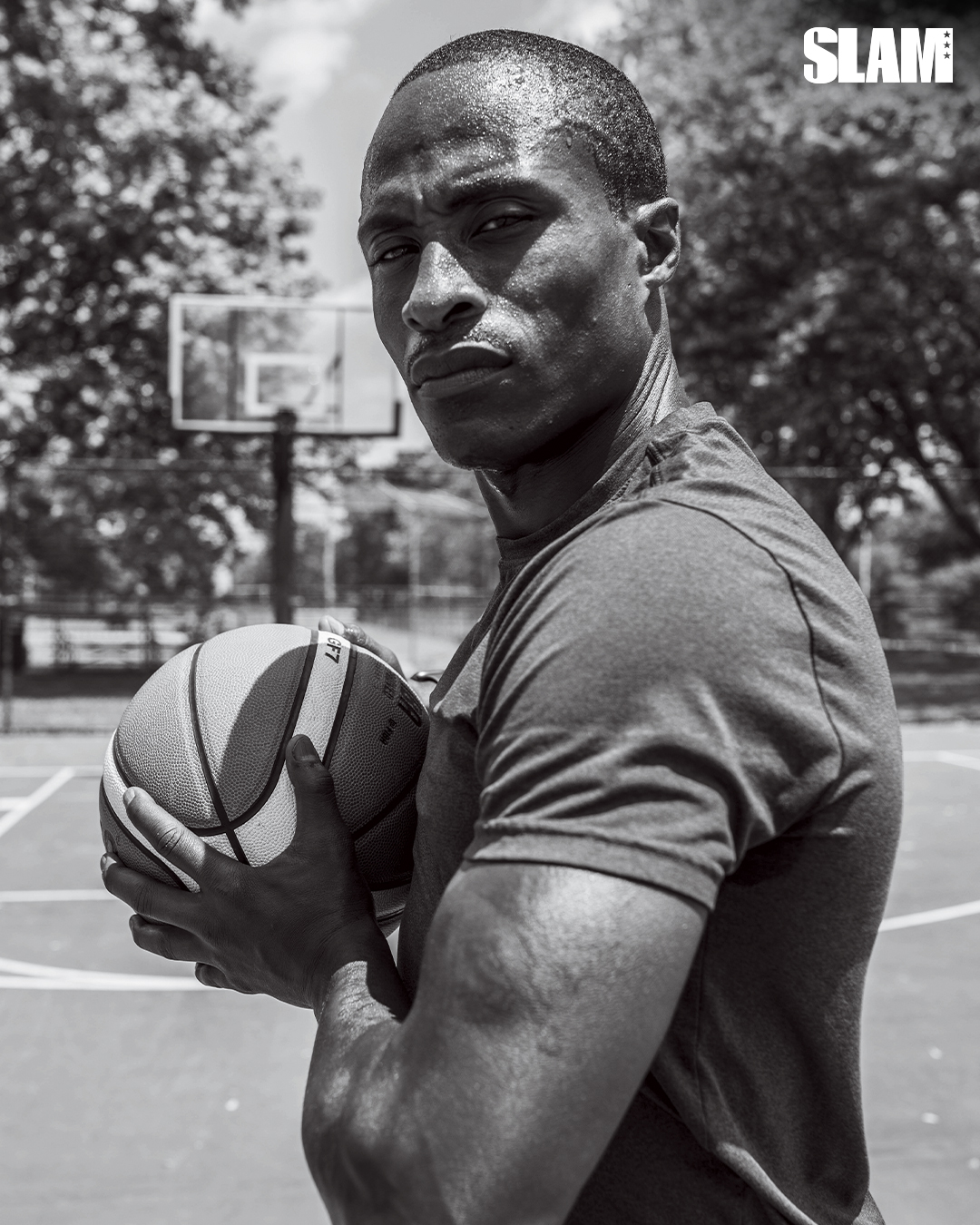

BROWN

For Rayshawn Brown, junior high school was a little different. He was busy putting on a show, but it wasn’t happening anywhere near a basketball court. By age 13, he was performing in the Big Apple Circus while attending a performing arts school on a dance scholarship. “My whole upbringing from elementary school, middle school and even high school was performing,” Brown says. “I danced. I performed at Alvin Ailey. I performed at the Dance Theater of Harlem. I did countless shows from African dance, modern, hip-hop, jazz, breakdancing.

“That was more amazing to me than just being able to dance and foot movements,” Brown adds. He only scratched the surface of his athletic ability. At the age of 15, the height of Rayshawn’s tumbles caught the eye of coach Frank Sellitto.

“Oh my God, Ray, watch out,” the coach yelled, as Ray was practicing round-off back handsprings on the basketball court. He easily landed on his feet and was caught by surprise when Coach Sellitto asked if he knew how close his head was to the rim while he was in the air. Clueless, Ray went to try again to see how high he could get.

“I did it again, and once I realized how I jumped to do my back tuck, I said, Holy shit, I could jump really high,” Brown says about his first time meeting a basketball rim at eye level. His intrigue would turn to passion after meeting former NBA pro Steve Burtt, who took Brown under his wing as a mentor.

The tie that bound the “Jersey Four” of Danny Reyes, Keshon Moore, Rayshawn Brown and Jarmaine Grant together before the night of April 23, 1998, was the game that we love. For many Black and Brown kids, the sport of basketball is that of circumstance. Without it, there’s no reason for many to stay on the straight and narrow. Without it, there’s no reason to try and go to college and beyond to create better opportunities for the generations that follow. It’s the reason you chase the game.

After a two-year stint at Westchester Community College in Valhalla, NY, Moore enrolled at North Carolina Central to play DII ball. The stay didn’t last long—he returned back to Manhattan after a redshirt season. His place on the depth chart dealt a steady blow to his confidence.

Under the mentorship of a Hall of Famer and after leading one of Rice High School’s two varsity squads in scoring, Grant was surprised when major scholarship offers weren’t on the table upon his graduation in 1993. Instead, he enrolled in Westchester Community College, where he met his roommate and teammate: Keshon Moore.

Reyes’ hoops journey sent him on an odyssey that included stops at Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College in GA, New York City Technical College and a league in Puerto Rico. A bone bruise to his knee in 1997 didn’t help.

Brown, at the behest of Burtt, became a mainstay at Manhattan’s Basketball City: an indoor facility with some of the best open runs in the city. Knicks stars like Allan Houston, Charles Oakley and Anthony Mason were all regulars. A late bloomer to the game with no high school hoops record to reference, Brown trained with Indiana Pacers point guard Travis Best and AND1 Mixtape star Tim “Headache” Gittens, and he made a name for himself at local showcases in an attempt to achieve an athletic scholarship. At age 19, Brown crossed paths with Moore in NYC and struck up a friendship. The two would meet for workouts and pickup games across the city; it was a bond that revitalized Moore after his stint at North Carolina Central.

Moore, who wanted to get his scholarship back, decided to give the 12-hour drive one more shot and attend an informal tryout at North Carolina Central. And he made plans to bring Grant, Brown and Reyes with him.

“North Carolina Central was the epicenter of everyone’s workout,” Grant says. “You would see Vince Carter work out there, Rodney Rodgers, Tracy McGrady work out there—it was the school to go to just run. Scouts would always be there, and we knew we weren’t going there just to work out for North Carolina Central.”

Eyes from surrounding colleges, HBCUs and professional leagues in China and Europe were expected to be there. This would be a chance for all four of the guys to play in front of highly influential members of the basketball community.

But the Jersey Four never made it to the gym.

Moore had taken the trip to North Carolina Central plenty of times on a Greyhound bus, but this time he called in a favor from his girlfriend’s mother, who rented a van in her name for Moore since he wasn’t of legal age to do so. Excited and optimistic about the journey, Moore picked up Brown, and the two booked it uptown to scoop up Grant. Then they grabbed Reyes, who had just picked up a fresh pair of Nike Air Pippens and the new DJ Clue mixtape. They began the drive with Jay-Z and Jermaine Dupri’s “Money Ain’t A Thang” on repeat. Times were good.

“I was away at school, but I knew my license was dirty,” Moore says. “It was suspended [for unpaid parking tickets], so I made sure I was going the speed limit. I’d never even been pulled over before, so I’m not even thinking about police officers.”

“There was no conversation, no dialogue. All I saw was a gun in my face,” Moore recalls. “It took about three seconds from the time I stopped the car and after that, I saw the sparks fly.”

The quickness that helped him so much during his basketball journey possibly saved his life, as Moore quickly jumped into the back of the van and ducked his head to avoid the gunfire. Grant, passed out in the back seat, awoke from his sleep to a kneecap shattered by a bullet.

“I woke up in a state of shock, because dreams don’t hurt,” Grant says. “All I see is chaos. I couldn’t see Rayshawn or Keshon. I could only see Danny. So any time I tried to move, I got hit with another bullet. Eventually I stopped moving, and by that time I couldn’t move. I was already shot four times.”

Slumped over to the side of the van, Grant could now see a clear vision of the police officer shooting at him. Confused as to why he was being shot at, Grant watched as a cop pointed his handgun at a defenseless Reyes, who put his hands up and pleaded with the state trooper to stop shooting.

“I kept yelling, Yo, the car is not in park! I tried to show him my hands to let him know I’m not trying anything funny,” Reyes says. “He looked at me, cocked his pistol and started firing. I got shot twice in my arm, twice in my hip, and one of the bullets that’s still in my stomach today came from those initial shots. Point-blank range.”

In the midst of the chaos of gunfire, screaming and glass shattering, the car was still on the reverse gear and heading toward something even more catastrophic: oncoming traffic.

Reyes grabbed the steering wheel to try and get out of the way, but with the lights off and moving southbound, a Honda Civic collided with the van, then went left and slammed into a concrete barrier. Rayshawn lost grip of the sliding door that he tried to exit out of as a bullet shot at him from the side hit his chest, went through him and lodged into his forearm. Danny made one last gasp to guide the group to safety, and as the car began to move forward, another shot blasted Reyes right in the middle of his back, an inch from his spine.

As the van came to a stop in a ditch, the Civic burst into flames. (The two people in the Civic had jumped out before the car caught on fire and were OK.) The four guys were taken to different hospitals after several hours of arguments between the paramedics, fire department and the police, who seemed almost determined to delay the time needed to get the group medical attention.

Reyes, who took the brunt of the onslaught, was removed from the passenger side of the van and then handcuffed, despite having been shot twice in the arm. His face was put in the mud as he continued to lose a lot of blood. Paramedics arrived and an argument ensued about releasing Reyes’ cuffs so he could be loaded onto a stretcher and receive proper treatment. The two troopers—John Hogan and James Kenna—refused, stating that the four hadn’t been searched yet. “One lady paramedic just got tired of the back and forth, so she brought out a razor and just cut my clothes off,” Reyes says. “So now I’m just butt-ass naked on the muddy grass, and once they didn’t find anything, I was finally put in the ambulance.” He was airlifted to a trauma unit in Camden, NJ.

The only difference between the Jersey Four and the endless amount of Black lives lost at the hands of those sworn to protect and serve is that they somehow survived. Their survival is key to spreading the message in 2020 that enough is enough. Too many times have we seen officers discard Black bodies and not face justice. Too many times have there been Black men and women who’ve pleaded for protection and service only to be met with silence. But because these four survived, they have a voice. These aren’t isolated incidents. The system is fucked up. They can tell you the reason they were shot that day was simply because they were Black and Brown and the people who shot them enforce a system of oppression that would keep them from being punished for it.

Police tried everything to get them to fold. Brown woke up to see that the incident was all over the news and being referred to as a “shootout.” Interrogators tried to coerce Moore into second-guessing the character of his friends; they also tried to piece together a case accusing the four of carrying drugs (in actuality, all they had was the over-the-counter creatine you can get at GNC). Kenna and Hogan maintained that their lives were in danger from a van rolling backward; forensic tests showed that the van couldn’t have been moving faster than 4 mph, a fact corroborated by the people in the Honda Civic that crashed into the van, who saw it rolling very slowly.

The cops tried everything to make it look like what happened to these four men was justified. All bullshit.

Reyes, Grant, Brown and Moore received a settlement of close to $13 million in February of 2001 after hiring the inimitable Johnnie Cochran to file suit in April of 1999. The state of New Jersey didn’t accept nor deny any admission of guilt. The two officers were indicted for attempted murder and aggravated assault, charges that were eventually dropped, though they were both forced to resign after pleading guilty to lying to investigators and falsifying documents to hide the fact that they had stopped minority drivers because of their race, according to the New York Times. Hogan testified that 75 officers told him to lie and that some of them brought him back to the scene of the incident to help him prep a more believable story.

These four men are remembered mostly by the incompetence of a broken police force. They should be remembered for their love of the game. They should be remembered for all of the endless nights and hours they put into that roundball and what it can do for you.

The guys are now using the experience for good—Moore and Grant are working on a new product with UC~Entelligence—a Black-owned start-up that specializes in mobile app and software development—that is being designed to help people in situations like the one they were in, facing police brutality and social injustice.

Meanwhile, the Jersey Four remain a miracle because they’re still here to tell their story. For the sake of those who can no longer speak after being silenced by police violence, do one thing when a Black person tells you about their experience with law enforcement: Listen.

—

100 percent of proceeds from SLAM’s new issue will be donated to the Social Change Fund. Grab your copy here.