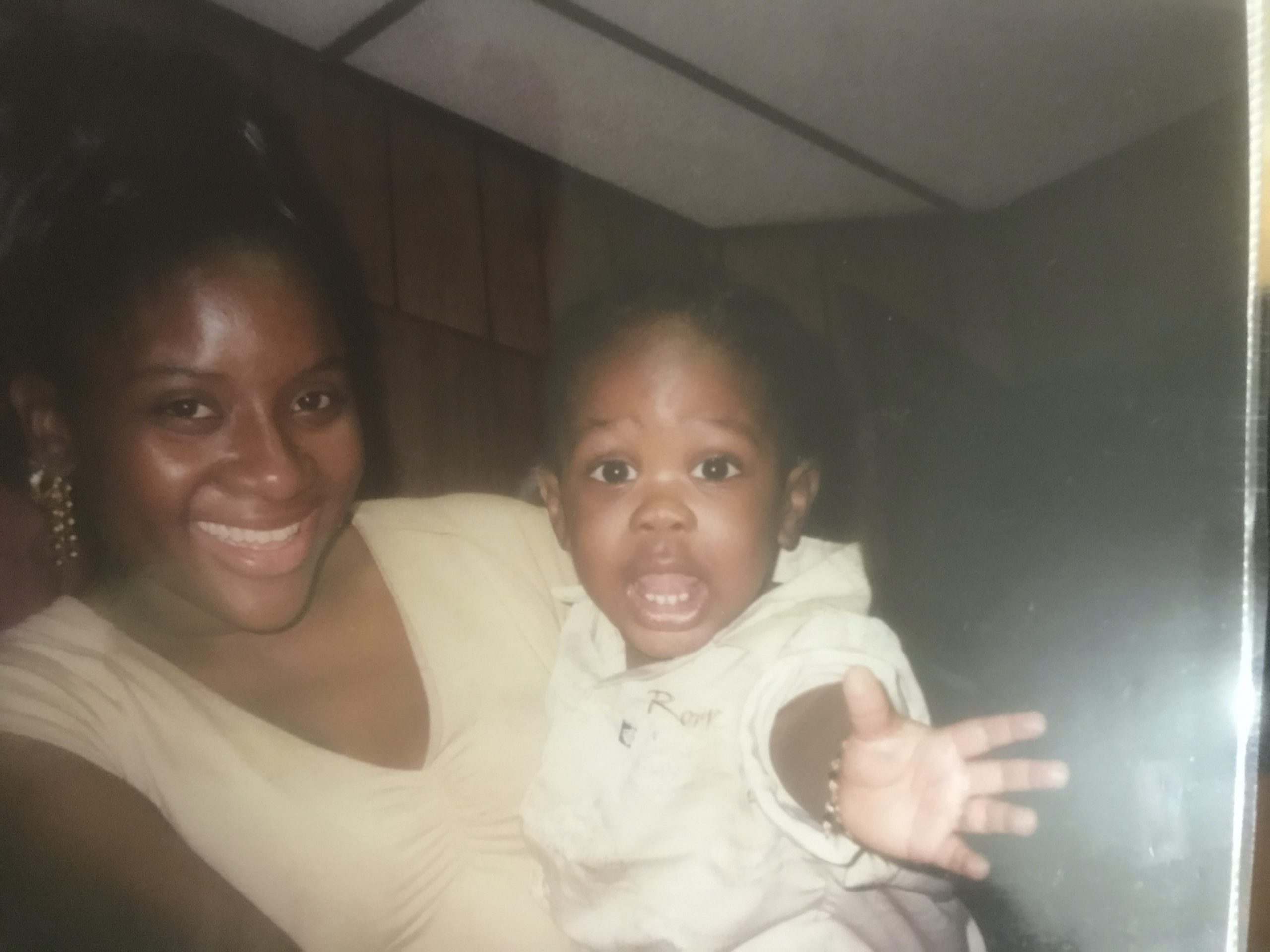

It was the light that he had. That’s what stood out to her most in the photo of her son. How angelic he looked. How happy he looked. How the light not only radiated onto his face but shined through him. It’s one of Osmine Clarke’s favorite memories of her 19-year-old son, Terrence, who tragically passed away in a motor vehicle collision in Los Angeles on April 22, 2021.

“We called Terrence and said, Terrence, is that a filter? And he was like, Mommy, that’s just me! Like, he just had this beautiful light,” Osmine recalls on a rainy afternoon in August, exactly four months since Terrence passed. She’s sitting down on a plush grey loveseat inside the dimly lit, yellow-painted living room at her mother’s house in Boston, telling the story.

She remembers she was at an IHOP in Brockton with her daughter Tatyana when she saw the photo on March 19. That same day, Terrence had declared for the 2021 NBA Draft, and in what appears to be a screenshot of a Face Time call, Terrence is looking slightly away from the camera and smiling a wide, cheeky grin as the sun beams down on him. The words, “Guess who just declared for the draft! Congrats broo I’m so proud of you” are written in the caption.

“His melanin was definitely poppin’,” says Taty, who is standing behind the couch while entertaining her 4-year-old brother Gavin.

“He had this beautiful light,” Osmine adds, gently smiling at the memory. “It just looked so beautiful. I thought it was amazing, as if it was an angel. There’s so many things leading up to now and Terrence passing that, it’s almost like, I don’t want to say a premonition but it’s like, this is an angel but eventually we have to take him.”

Her voice breaks and the emotions start to overcome her. Gavin, who has just climbed up onto her lap, reaches over to a box of tissues on the wooden table beside them and hands one to her.

Here you go, Mommy.

“I think that everything leading up to the accident were, like, signs,” Osmine repeats. “But we could have never known that [then].”

SLAM 234 featuring the late-Terrence Clarke is available now. All proceeds from the sale of this issue will go directly to his Terrence’s family and the TClarke5 Foundation.

Terrence Adrian Clarke was born on September 6, 2001, a month after his expected due date, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. Even during the early years of his life, he always knew that he wanted to go to the League.

His father Adrian would often take him to Boston Celtics games as a kid, and at 8 years old, Terrence met his favorite player, Rajon Rondo, who told him to “keep working.” There’s a photo, Osmine recalls, from one of the games where Terrence is on the court and looking up at the basketball. The look on his face says, I’m going to be here.

“When he came back from the games he said, Mom, I’m going to be in the NBA. He just spoke it into existence, like, This is what I want to do.”

Brandon Watson, Terrence’s gym teacher at Young Achievers Academy in Mattapan, recalled a young boy who picked up the sport in second grade, showing a serious commitment to the game even back then, so much so that he’d cry whenever he had to finally leave the gym.

Growing up, Terrence spent most of his time at the Vine Street Community Center in Roxbury, where he trained with his mentor Dexter Foy, whom he met when he was entering fifth grade. Terrence was playing at Tobin Community Center in Roxbury when Dex and AAU coach Maurice Smith first noticed him for his height. They were looking for someone tall to join their team, the Titans, and that’s when Dex went up to Terrence and asked for his mother’s phone number.

That was the beginning. Not long after, Dex started taking his two sons, Jamari and Keon, and TC to work out at Vine Street, where he’d set up ballhandling and shooting drills. Even then, Terrence’s passion for the game was undeniable, and he showed a deep, innate desire to want to get things right. To want to do things the right way, regardless of what others think.

It made him emotional at times, both on and off the court. Osmine and Dex both remember the time when Dex took the boys to see one of the Fast and the Furious films at the Randolph movie theater. The other kids didn’t want to go, but T refused to do what the majority wanted. He was set on something happening, and like any kid would do, he threw a fit to get his way.

“He was like, Do you know everybody else didn’t want to go to the movies? And I still told Dex, I want to go regardless!” Osmine recalls, laughing. “And I was like, Terrence, you can’t be selfish! That’s typical Terrence. Have you ever seen him when he’s playing?” Osmine then gets up and starts mimicking Terrence pouting up and down the court, arms waving. “When you [saw] him go like this, that means he’s in his funk.”

Dexter says that during those moments, Terrence was just misunderstood. “He had so much passion on the court. He just wanted things to be right. I think that [came] from his training. You know, Terrence put in a lot of work. He was training so much that he just wanted everything to be right. And when it wasn’t right, I think it came off differently to people. But they don’t know what he’s gone through to get to that point.”

SLAM 234 featuring the late-Terrence Clarke is available now.

Terrence once said that he didn’t get much of a childhood because he was always playing basketball. He didn’t even learn how to ride a bike until ninth grade, Dexter later reveals. Terrence was in the gym, committing himself to workouts with his trainer Brandon Ball.

At first, Ball only trained the athletic shooting guard once a week, but that soon progressed into twice-a-week sessions. As Terrence got older, the two of them started working out every day, even twice a day. Ball would later pick Terrence up from his grandmother’s house at 5 am to train before school.

“You [didn’t] have to tell him things twice. He [got] it right away,” Ball says. “To the point where he could see something right away and go act it out in terms of every step that was in the movement, the rhythm of it. If you [taught] him a read, he [was] going to be able to pick that read up right away in the game, in live action. He’d get things so fast.”

After attending a camp at Syracuse University and heading into his sophomore year, Terrence told Ball how everything was starting to click for him on the court. All of his hard work was coming together. “He was like, B, it’s easy, now. I’ll never forget that. It was one of the moments when I really started seeing things turn for him. The confidence.”

Terrence brought that energy with him to the NBPA Top 100 Camp in 2018, where he averaged 10.4 ppg. Dexter went with him, and it was there that he saw Terrence hold his own against the other top prospects in the country.

“You heard rumblings of him having chances to make the NBA,” Dexter says. “But after we left that camp, [I remember] him and I talking and realizing that this is obtainable.”

That July, Terrence announced his decision to transfer to Brewster Academy. Doing so meant leaving his neighborhood, his friends and the familiarity of the city to live in rural Wolfeboro, NH. He once said that he made that sacrifice for not only his own future, but for his family.

While the adjustment was difficult at times, Terrence powered through to average a solid 15.9 points his first season. He then went on to average 16.2 ppg playing for Expressions Elite on the EYBL circuit that summer and earned an invite to Chris Brickley’s exclusive Black Ops runs. There, he trained with 10x NBA All-Star Carmelo Anthony and soon-to-be All-Stars Donovan Mitchell and Trae Young.

“The main thing I learned is that I could play with anybody—in the country, in the world,” Clarke told SLAM in 2019. “It doesn’t matter who it is, I feel like I can play with ’em. That built my confidence a lot.”

He then showed out that August at the SLAM Summer Classic Vol. 2 in NYC, where he joined a stacked roster full of elite high school prospects and future pros, from Jalen Green and Sharife Cooper to Jonathan Kuminga and Josh Christopher.

Following the grind of the summer, Terrence popped off his junior year, averaging 18.5 points, 5.8 rebounds and 3 assists in 37 games. He was ranked No. 4 in the class of 2021 by ESPN. He often said he aspired to “put Boston on the map” and prove that top-level talent can come out of the 617.

Osmine loved watching her son do his thing on the basketball court, and she’d always be at his home games at Brewster with a satchel purse made out of a basketball on one side of her, Gavin on the other. Her favorite hoop memory of T is from that season, when Brewster played against Catholic Prep in November 2019. She remembers it well, the way that her son soared to the basket after a fast break, effortlessly dishing the ball between his legs and jamming down a dunk. By the time he got his footing and landed to the ground, he blew a kiss to the cameras as if it was a performance. To him, it was. Terrence was always putting on a show.

As he continued to ascend, the hype followed in the form of thousands of followers and a blue checkmark on IG. “I think for him to get recognized for the hard work he put in, I think that was a good thing for him,” Dexter says. “I remember the first time he got verified. He was on cloud nine. [He called me] and was like, I got it. I didn’t even know what it [was]! I think that’s when he recognized that, you know, this is different.”

Terrence once said that he wanted to go to a school that would help get him “ready for the NBA.” After fielding offers from powerhouse programs including Duke, Boston College, UCLA and Kentucky, he finally held his college announcement ceremony in September 2019 at Vine Street.

With Osmine sitting by his side, a video played as Terrence stood up and unzipped his green-camo printed jacket to unveil a grey t-shirt with the words KENTUCKY WILDCATS printed in blue on the front. He would be reclassifying to the Class of 2020 and heading there in the fall.

Head coach John Calipari says that we didn’t get to truly see Terrence at his fullest during his lone season at Kentucky. After dropping 22 points against Georgia Tech and another 14 in a matchup against Notre Dame, Terrence injured his ankle on December 19 against North Carolina. Coach Cal says that he shouldn’t have played Terrence after that, despite the fact that doctors said he was OK and MRI results didn’t show any significant damage. And yet, after Terrence continued to let Cal know that his leg hurt, the team sent him to get an MRI/X-ray, which revealed a “stress reaction” in his leg.

“At that point, I thought the season was over. He and I were in the office. He cried. I cried,” Cal tells SLAM. “Can you imagine being 19 and your career flashing before your eyes? You had aspirations and opportunity, and you come to Kentucky, you’re one of the top 10 players in the country. But he did stay positive. He would tell the team, I’m coming back next week.”

Three months later, on March 11, Coach Cal let Terrence get on the floor for the last game of the season against Mississippi State. He scored 2 points and had 3 assists in nine minutes. “Even then you could see just a glimpse, and you’d look and say, He made plays normal guys couldn’t make,” Cal says.

After his charismatic freshman signed a deal with Klutch Sports in April, Cal had heard that Terrence was getting stronger and better. “They said it was off the chain, how he was playing, what he was doing, how he was training. His athleticism. His leg was better and he was back. He was on that path.”

Terrence’s life ended too soon for him to see the dream he spoke of being manifested into a reality. On July 29, the NBA selected him at the 2021 NBA Draft as an honorary draft pick, with Osmine, Taty and Gavin on hand at Barclays Center to accept the recognition on his behalf.

Later this fall, with the support of Mayor Kim Janey and the city of Boston, the Celtics and New Balance plan to unveil a newly renovated home court at Vine Street that will be renamed and dedicated to honor his legacy.

Terrence’s memory will live on there, and through his family, especially Gavin. The similarities between the brothers are undeniable, from the magnetic personality to the height: at 4 years old, Gavin is already four feet tall. He’s also starting to develop a love for the game and can dribble two basketballs at one time. Osmine has started taking him to the gym on Saturdays to train with Brandon Ball.

There, Ball has noticed that Gavin has Terrence’s same energy. Just as T would cheer and clap his hands out of excitement, Gavin is a little hype man. “He’ll watch other guys working out and when they make shots, he’ll go crazy,” Ball says. “Like Terrence, he’s a big motivator.”

During the final moments of his life, Osmine and Dex say that Terrence was happy. Truly happy. The light in him was shining brighter than ever. On the day he passed in April, he was laughing and smiling with them outside of the training facility. He was hyped about a full-court run that was scheduled for the next day. He was ready to show what he could do out there.

After finishing up his workout, they both remember Terrence excitedly going up for a dunk, the first time he’d been able to do so in about a month. His confidence was sky high.

“He was like, Mommy, I’m so much stronger,” Osmine says. “I’m saying this now, but I would have never said this if Terrence was alive: I think that God put us through that moment to be there for him, and to see his last smile.”

SLAM 234 is available now in black and gold metal editions, as well as these exclusive cover tees. Shop here.

All proceeds from the sale of the regular issue, metal editions and the cover tee will go directly to his family and the TClarke5 Foundation, which you can donate to here.

Photos via Getty Images, University of Kentucky Athletics and the Clarke family.