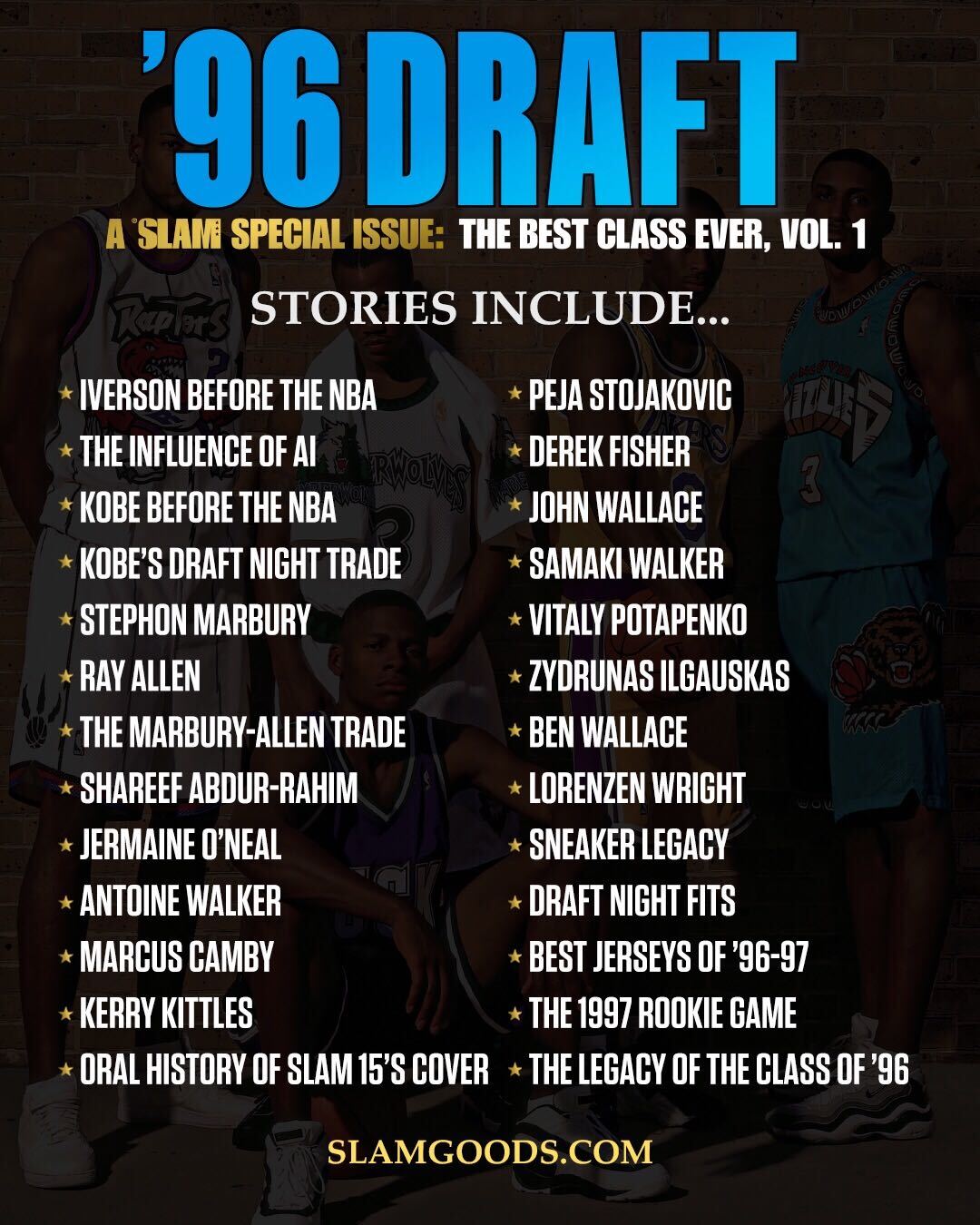

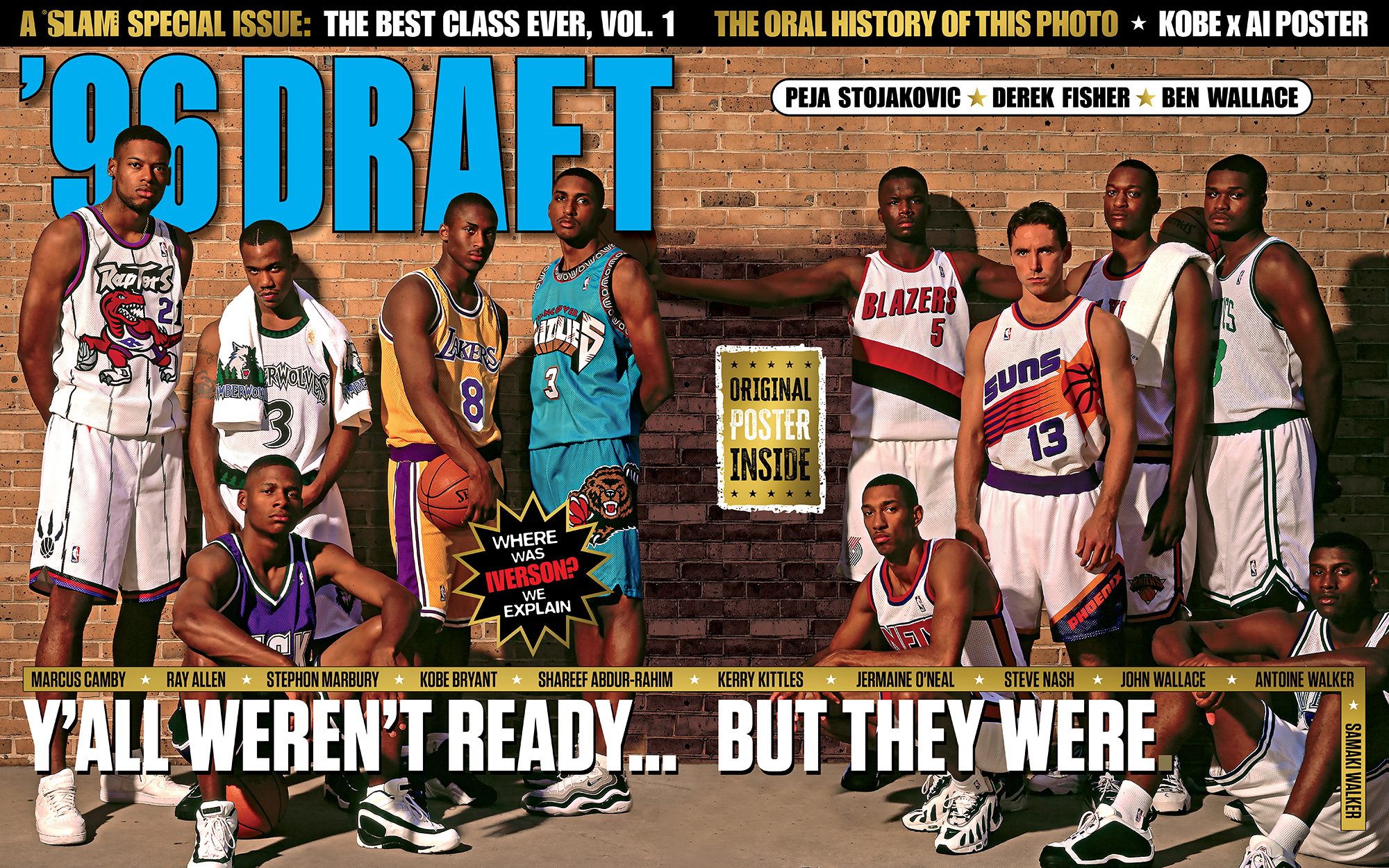

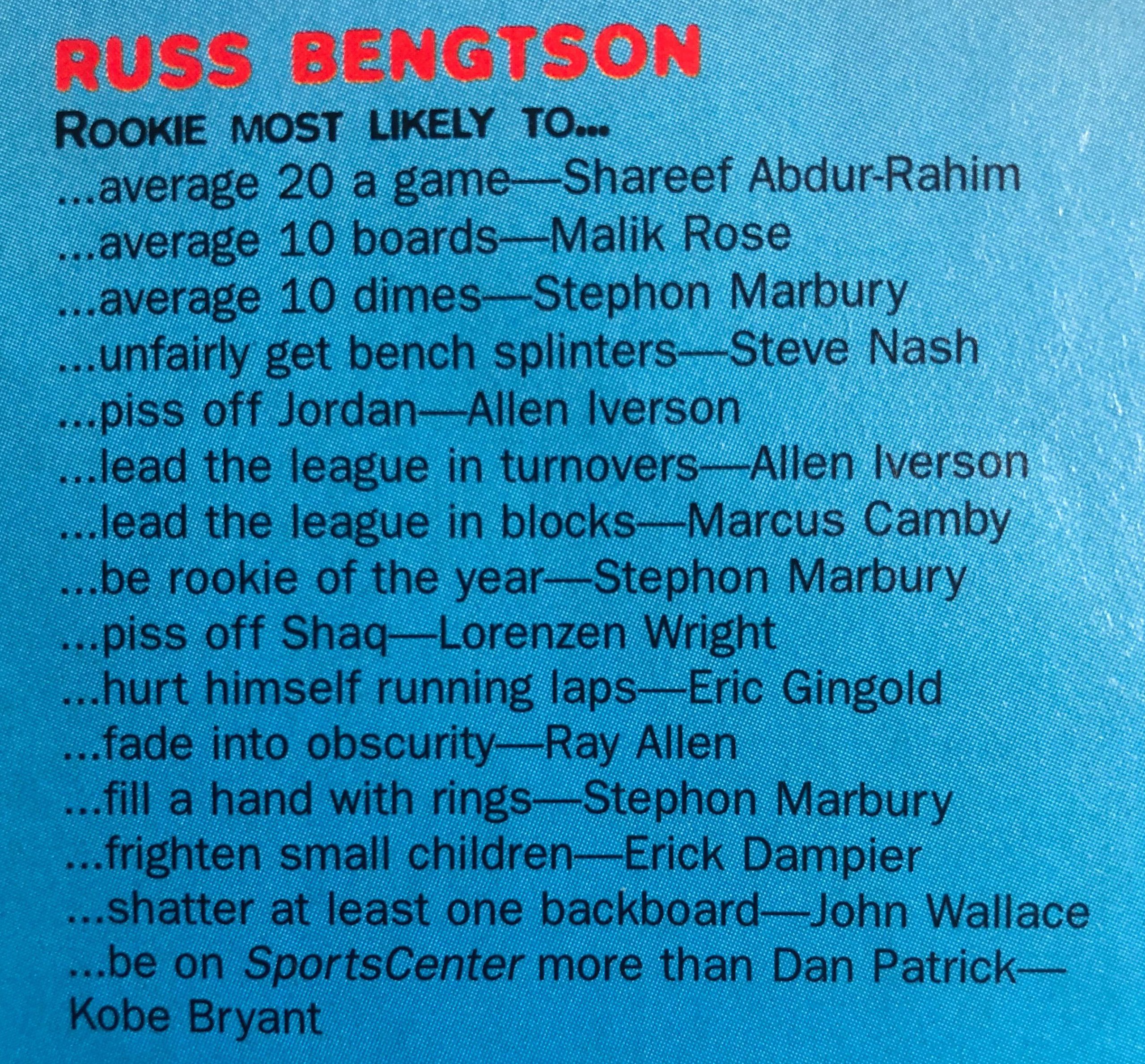

In the entire 70-plus year history of the NBA, just 135 players played 1,000 games or more in their careers. (Glen Rice is 135th, with exactly 1,000—Paul Millsap, who has played 996, will become the 136th early next season.) Ray Allen currently ranks 22nd, with exactly 1,300. Next year he’ll drop to 23rd, as LeBron James—currently at 1,265—continues to rampage his way up the all-time lists. Allen played in more career games than John Havlicek (1,270), Hakeem Olajuwon (1,238), and Shaquille O’Neal (1,207). Of his celebrated 1996 draftmates, only Kobe Bryant (1,346) played in more, and not by much. Allen’s career lasted 5.78 Todd Fullers or 2.56 Kerry Kittles. All of this is a roundabout way of saying that when I picked Ray Allen as the 1996 rookie who was “Most Likely to Fade into Obscurity,” I could not have been more wrong.

Twenty-four years later, I am hard pressed to remember why I selected Allen for such a dubious distinction. Maybe there was a little backwards praise in there—after all, to fade into obscurity you have to be non-obscure to start. And Allen certainly was that. He’d been a high school star in South Carolina, played in Nike’s summer camps, and spent three years at UConn battling the likes of Kittles and Allen Iverson in Big East tournaments. He entered the draft as a no-doubt lottery pick and Michael Jordan picked him to be one of the faces of the new Jordan Brand. Did I pick him because he landed on the Bucks? Maybe that was part of it.

Here is something I certainly did not consider when I put his name down—how Ray Allen, 20-year-old NBA rookie, would feel when he saw it. It seems obvious now, in these days of Twitter and the like, but back then everything seemed at a further remove. Yes, I distinctly remember getting a huge—and entirely unexpected—hug from Allen Iverson when I gave him copies of the “Who’s Afraid of Allen Iverson?” issue in the dingy visitor’s locker room at Madison Square Garden, but that was a COVER. Who read all the little stuff? Well, Ray Allen did.

“I remember being excited because this was probably one of the first magazines I was ever on the cover of.” It’s September and Ray Allen is speaking over Zoom from Connecticut. Ready or not, here it comes: “And then just seeing the accolades on the inside cover, you look for any recognition whatsoever. I know so much was said about Allen and even Shareef, because he was a prodigy at such a young age, and Camby being 6-11, and having so much upside for the NBA, so I was just curious what people thought about me. And then all of a sudden you see this list and my shoulders drop, because it really bothered me. Even though at the time I knew what ‘obscurity’ meant I had to look it up in the dictionary because I wanted to make sure that I had it right.”

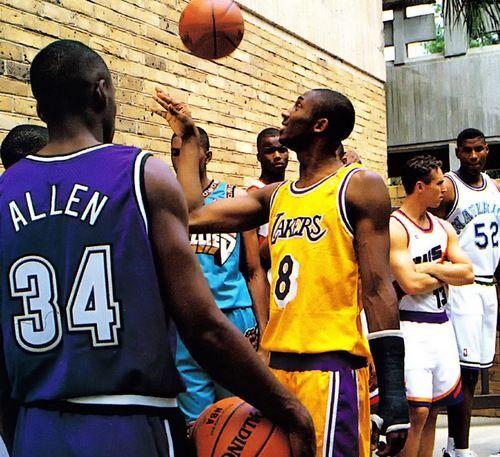

Let’s rewind a bit to the draft itself. Allen had worked out for the Sixers and the Raptors and the Grizzlies and the Bucks, and felt sure he was going to be a top-four pick. So when the Timberwolves, picking fifth, called shortly before draft day and wanted him to come in, he brushed them off. Then, right before the draft, he got a call in his room from ML Carr and Red Auerbach, informing him that if he somehow fell to sixth, he’d become a Boston Celtic. For Allen, who’d spent three years in the Northeast, this was a dream scenario. And when Milwaukee selected Stephon Marbury, he thought that dream was about to come true.

“So bam, Minnesota is on the clock and the cameras come over to my table,” he says. “And I was so confused. I couldn’t believe what was happening, I was angry. Why would you pick me and you got JR Rider already on your roster?” So Allen shakes hands with David Stern, goes to the back, dutifully does his interviews with the media. “I’m having a conversation with people from Minnesota, their local news stations, and I’m over here filibustering on what it’s gonna be like with JR Rider.” And five minutes later he’s pulled aside. There’s been a trade.

“When I look back on that draft class,” he says, “I just remember one of the things that stood out to me the most was how much I had no clue what was taking place. I didn’t know about trades, I didn’t know about manipulating your position.”

Swapped from Minnesota to Milwaukee for Marbury, Allen then endures a number of indignities in rapid succession. First, he’s traded before he can even celebrate being an NBA player. Second, his family gives the Marburys the Wolves draft hats and don’t get the Bucks ones back. Third, he’s put on the phone with Milwaukee media, who helpfully tell him that the fans gathered at the Bradley Center are booing the trade. And fourth, in the first draft where salary slots are based on selection, he’s picked fifth but goes to the team picking fourth. “To this day I tell Stephon that he owes me 200 grand, because that was the difference in salary from the fourth to the fifth pick,” he says. I can’t help but laugh. “Yeah, laugh about it, but I never seen my money though.”

That’s just additional context to why that “fade into obscurity” thing may have hit so hard—context I certainly didn’t have. (To be fair, it probably wouldn’t have mattered either way.) And it helps explain his immediate reaction. “The first five or six years in the NBA I didn’t want to talk to SLAM Magazine at all because I felt like they had said something against me or stained my name or whatever that may be,” Allen says. “But then as I started to grow and mature I realized how good and how important it was—you had no idea who I was, you had no idea what my heart was or what my desires or intentions were in professional sports, and so it made me have to dig inside who I am and who I was. That was so important to me and it helped me kind of focus in and do what I needed to do to be successful.”

Allen played all 82 games as a rookie, starting in 81. He started every single game the Bucks played the following season, and the next three seasons after that. He was named second-team All-Rookie, and in his fourth season, made the first of three consecutive All-Star appearances. He’d eventually be a 10-time All-Star, win two rings and be inducted into the Hall of Fame. Allen’s career was defined by his meticulous preparation and his flawless jumper—the first which honed the second and enabled him to consistently perform at a high level from the first minute of the first game to the final seconds of the last every single year. He was a student of the game and a student of everything else, always bringing a book or books on every road trip. My most common question to him over the years, once he resumed talking to us, was: “What are you reading?”

After that 1996 cover, I participated in plenty more “Rookie Most Likely To…” lists, picked more “fade into obscurity” guys. Without looking them up, I couldn’t tell you who any of them were. The only reason I remember I picked Allen is because Allen himself reminded me. It’s come up in our conversations before, and he cites it as one of the reasons he worked as hard as he did. “Those types of mentalities of not accepting mediocrity and not fading into obscurity are so important for people who think that they are good,” Allen says. “Being the best sometimes allows you to be mediocre because you don’t work and get better, and I think reading that in the magazine, not understanding the lesson in the beginning—you didn’t [write] it because you knew me, you just did it because you were figuring out how to place or rank this class, and me after understanding this, I said, You know what, this was a godsend for me. I needed to hear this. I needed somebody to tell me I wasn’t what I thought or hoped to be and I need to work on this forever.”

Here’s what I think. I think this is who Allen was the whole time. If I didn’t say it, if I didn’t provide the impetus, someone or something else would have. It’s like Michael Jordan—sure, there was the “that’s when it became personal to me” moment, but if it wasn’t this, it would have been something else. “Fade into obscurity” may have sent the charge, but the wiring? That was already there.

GRAB YOUR COPY OF SLAM PRESENTS ’96 DRAFT FOR EVEN MORE GOODIES FROM THE ISSUE

“Some players in every sport, when they make it, when they get drafted, they think that they made it, but making it is not just getting there—now the real work begins,” he says. “You don’t ever think that you’re good. If you think that you’re good, then that’s as good as you’re ever going to be.”

This is all starting to feel very Terminator 2, “the future is not set” and all of that, floppy-haired Edward Furlong firing up a dirt bike as Guns N’ Roses blares. But there is a time travel aspect to all of this, predictions being made in the past by GMs as well as writers that wouldn’t be proven out for 20 years on, putting stardom expectations on a bunch of 20-somethings—and in some cases teenagers—who had yet to step foot on an NBA floor. It’s kind of a “you make your own luck” thing, too, and now that I have mixed up Terminator and Titanic, I should find a way to wrap this up before things get really out of hand.

But the hell with it, let’s let things get out of hand. Allen himself brings up the movie Midway—one I haven’t seen—as a way of illustrating the difference between living through something and the way the story is told afterward. When you’re going through it, it looks different. “We get that because of history, because of historians,” he says, “and I think that’s what the great thing about what you do, what the magazine does, because it records all the events that have taken place—the games that have been played, the players that have played in them, but now we have to have the stories that take place in between each one of these moments to bridge the gaps and tell the human side of these statistics.

“We shared a journey together and hopefully our stories help people live better, not only in the athletic world but in life in general.”

You hope to get closure but sometimes you don’t. This year started out like most any other, and then Kobe Bryant died in January, and a global pandemic hit, and it was all one giant reminder that no one really knows what the future holds. “With Kobe passing, it really shed light on just the idea of how you don’t have enough time,” Allen says. “I thought at some point, some day, we’d be sitting around talking about everything that we went through and what it was like. And as Kobe is no longer with us, God rest his soul, that’s one part of the human side that we no longer can appreciate or experience because a lot of his stories, if he didn’t have it written down somewhere or he didn’t share it with another player, then it’s part of our history, part of basketball culture that we lost forever.”

I thought the same thing. So I finally take the opportunity to apologize to Allen for the long-ago slight, the prediction that thankfully didn’t come true, that in fact became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy in reverse. Allen rejects the apology, because that’s who he is. It’s who he always was. And of course, had I known this, I never would have made the damn prediction to begin with.

—

SLAM PRESENTS ’96 DRAFT IS AVAILABLE NOW.