Writer Pete Croatto‘s new book, From Hang Time to Prime Time, examines the NBA’s rise to the global business that it has become since the 1970s. The following is an excerpt from the book, which is currently available.

—

About Last Night, based on David Mamet’s acidic and observant play, Sexual Perversity in Chicago, and directed by Ed Zwick, is the epitome of a mediocre movie. “You’ve a right to wonder why anyone would want to work so hard—with such an expenditure of imagination—to transform a play with such a distinctive voice into a movie that sounds like any number of others,” wrote Vincent Canby in the New York Times. But in the summer of 1986, a bubbly romance starring two members of the short-lived Brat Pack was an obvious to-do that carried an unforeseen cultural impact.

Riswold and Davenport, coworkers at Portland, Oregon–based ad agency Wieden + Kennedy, were in Los Angeles to edit a Jordan spot for Nike. They decided to catch About Last Night . . . . Riswold deemed it “terrible.” The highlight came in the coming attractions, long before Rob Lowe and Demi Moore’s stylized romantic travails.

“Tube socks! Tube socks! Three for five dollars! Three for five dollars! Three for five dollars!” a slight, young African-American man bellowed to a procession of disinterested pedestrians. Then he turned to the audience, all puckish confidence.

“Hi, I’m Spike Lee and when I’m not directing, I do this. It pays the rent, puts food on the table, butter on my whole wheat bread. Anyway, I have this new comedy coming out, this very funny film: She’s Gotta Have It. Check this out.” Then the proper preview, illustrating a New York City love rectangle between the gorgeous graphic artist Nola Darling (Tracy Camilla Johns) and three very different suitors. The film was shot in sultry black and white and featured not a trace of Hollywood slickness, including expensively coiffed white folks and Sheena Easton tunes. Everybody on-screen looked and acted like a real person. It was the opposite of the high-concept misery Riswold and Davenport were doomed to endure.

Lee returned in vivid color.

“So, you’re bugging out, right? Yougonnagoyougonnagoyougonnago? If you don’t, I’ll still be here on this corner.”

This is somebody worth seeing, Riswold thought.

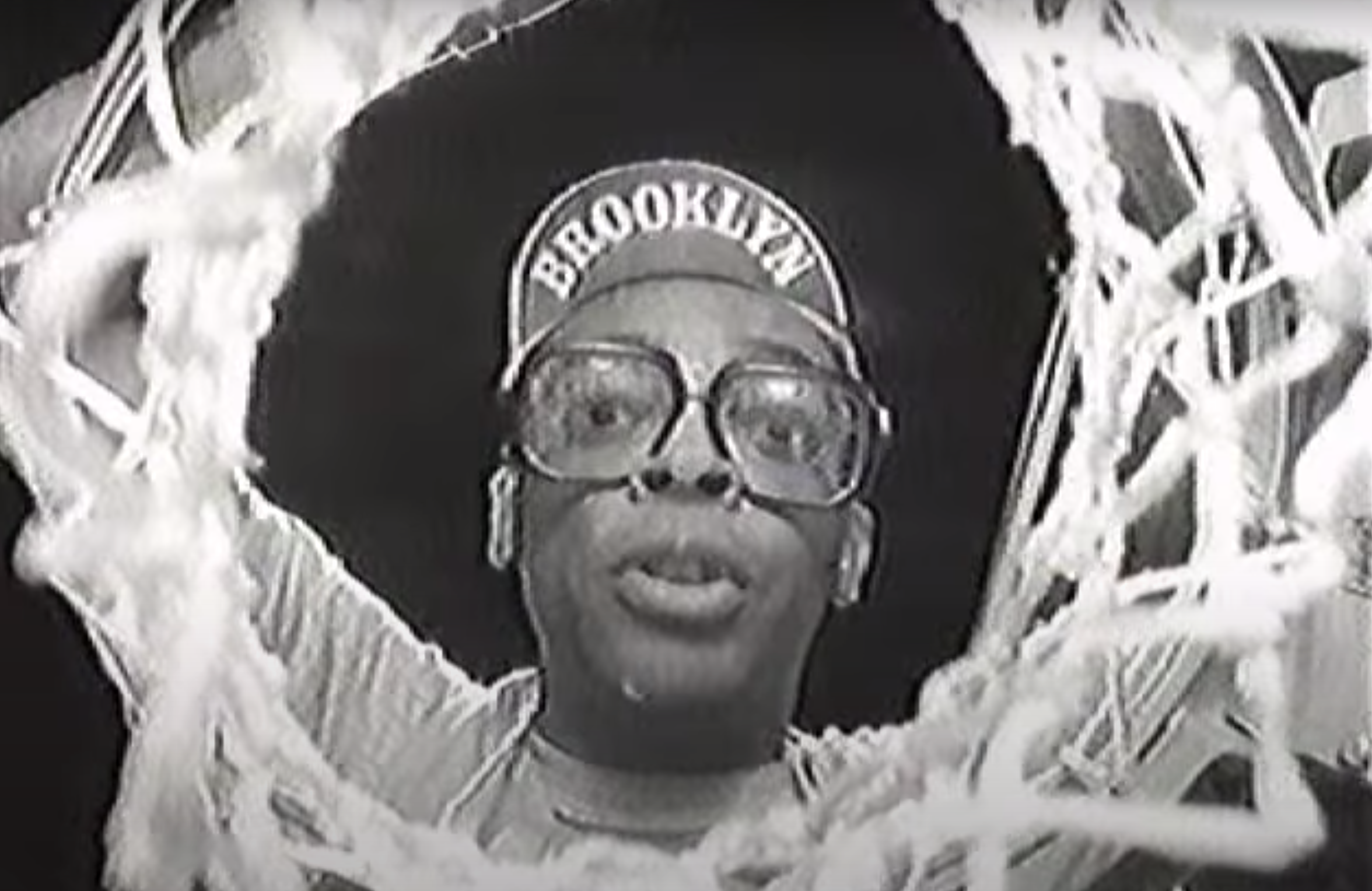

The admen answered the young filmmaker’s plea and saw his debut feature back in Portland. Lee played one of the men vying for Nola’s affections. Mars Blackmon was a motormouthed, bespectacled city kid who worshipped at the altar of Michael Jordan and Nola. It was a close race as to who was more important.

Then, said Riswold, came the “wonderful, serendipitous stubbing of the toe.” In a memorable scene, Mars has sex with his dream woman in his Air Jordans. Riswold said he and Davenport turned to each other and said, “You’d better be thinking what I’m thinking.” Davenport, in particular, loved She’s Gotta Have It. It was so different and new. Mars Blackmon popped from the screen. Davenport said Riswold saw the opportunity to unite Blackmon with his basketball infatuation. The idea was too much damn fun to pass up, especially if the hip, young director with that unapologetic style worked behind the camera.

Davenport hounded Riswold, a brilliant and prolific talent, to see if he had written the script for the commercial. In the middle of the night. The next morning at work. Then an hour later. “Once it’s on paper,” said Davenport, who didn’t recall this follow-up, “you can react to it and you can make sure everyone is on the same page.”

“Shut up!” Riswold finally said. “I’m trying to write the script!”

Wieden + Kennedy had Nike as a client; Jordan was a layup. Lee was a different story. He picked up his office phone and dialed 718-555-1212, information for Brooklyn. He asked for Spike Lee. Soon Davenport was speaking to the future director of Do the Right Thing, Malcolm X, and Black KKKlansman. Davenport couldn’t believe his luck and gave Lee the pitch.

“Bullshit,” Lee replied. “Who is this?”

Davenport finally convinced the auteur he wasn’t a film school classmate pulling an awful prank. It sounded great to Lee, who had craved this kind of exposure since graduating from film school. The lifelong Knicks fan would star and direct the commercial (a rarity for African-Americans back then), take home a $50,000 paycheck, and work with Jordan. This was sweet vindication. Nike gave Lee only a Jordan poster—which hung in Mars’s bedroom—for the film. That was it. The director had to buy two pairs of Air Jordans out of his own pocket. Now he was poised to be the face of its ad campaign alongside one of America’s most popular ath- letes. That’s the way it had to be. Lee owned the rights to the Mars Blackmon character, Davenport said, and nobody knew Mars better than the guy who created him and played him.

Nike couldn’t have asked for a better partner. Lee knew sneakers represented more than footwear. They defined a person. DJ Clark Kent believed Lee created sneaker culture. Nike played a memorable role in She’s Gotta Have It. The kicks received another stage two years later in Do the Right Thing, Lee’s brilliant drama about racial tensions boiling over on a scorching day in a Brooklyn neighborhood. When Buggin’ Out’s white, pristine Jordans—108 American dollars, with tax—are scuffed by an indifferent bicyclist, a passel of Bed-Stuy allies deem them “fucked up” and ready for the trash. A brief, potent argument on racial politics ensues.

“Yo, what you want to live in a black neighborhood for anyway, man?” the black Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito) tells the white man (JohnSavage),who owns a brownstone. “Motherfuck, gentrification.”

“As I understand, it is a free country, a man can live wherever he wants,” says the building owner, who sports a Larry Bird shirtsey.

Buggin’ Out is nonplussed. “Free country? Man, I should fuck you up for saying that stupid shit alone.”

*At that point, Kent said, the Jordans became a character.*

Riswold and Davenport didn’t feel like they were about to enter risky territory. For one thing, Davenport said, Nike had total faith. “Nike ads back then weren’t as iconic or held to such high esteem and regard as they are now because we were just starting out,” Davenport said. Phil Knight was so averse to research and marketing that Scott Bedbury, Nike’s worldwide advertising director from 1987 to 1994, was warned not to mention either to Knight. Bedbury finally asked his boss why. “Marketing?” Knight scoffed. “That’s what other companies do. We don’t do that here.” What Knight abhorred was traditional advertising, which Wieden + Kennedy avoided. Both parties believed that didn’t work anymore.

Riswold’s scripts, featuring Mars expounding on various topics, were terrific. Davenport could visualize Lee saying the lines as Mars. Riswold gave Mars and Jordan dialogue that sounded comfortable, not a thinly disguised sales pitch. And it told a story.

“Jim is the mastermind behind that, hands down” Davenport said.

“It’s not all that hard,” Riswold said. “It really isn’t. My sisters know how stupid I am. Advertising is very, very simple. It’s just populated by people who have very little to do but to make it difficult.”

Wieden + Kennedy had reservations. “We were doing Honda scooter commercials at the same time with Lou Reed and Grace Jones,” Riswold said. “There were questions: Are we pop culturing Nike? Are we turning them into Honda?” But Riswold said agency heads David Kennedy and Dan Wieden saw how excited he and Davenport were about the pairing. And if they fucked up, Riswold half-joked, they’d only lose their jobs.

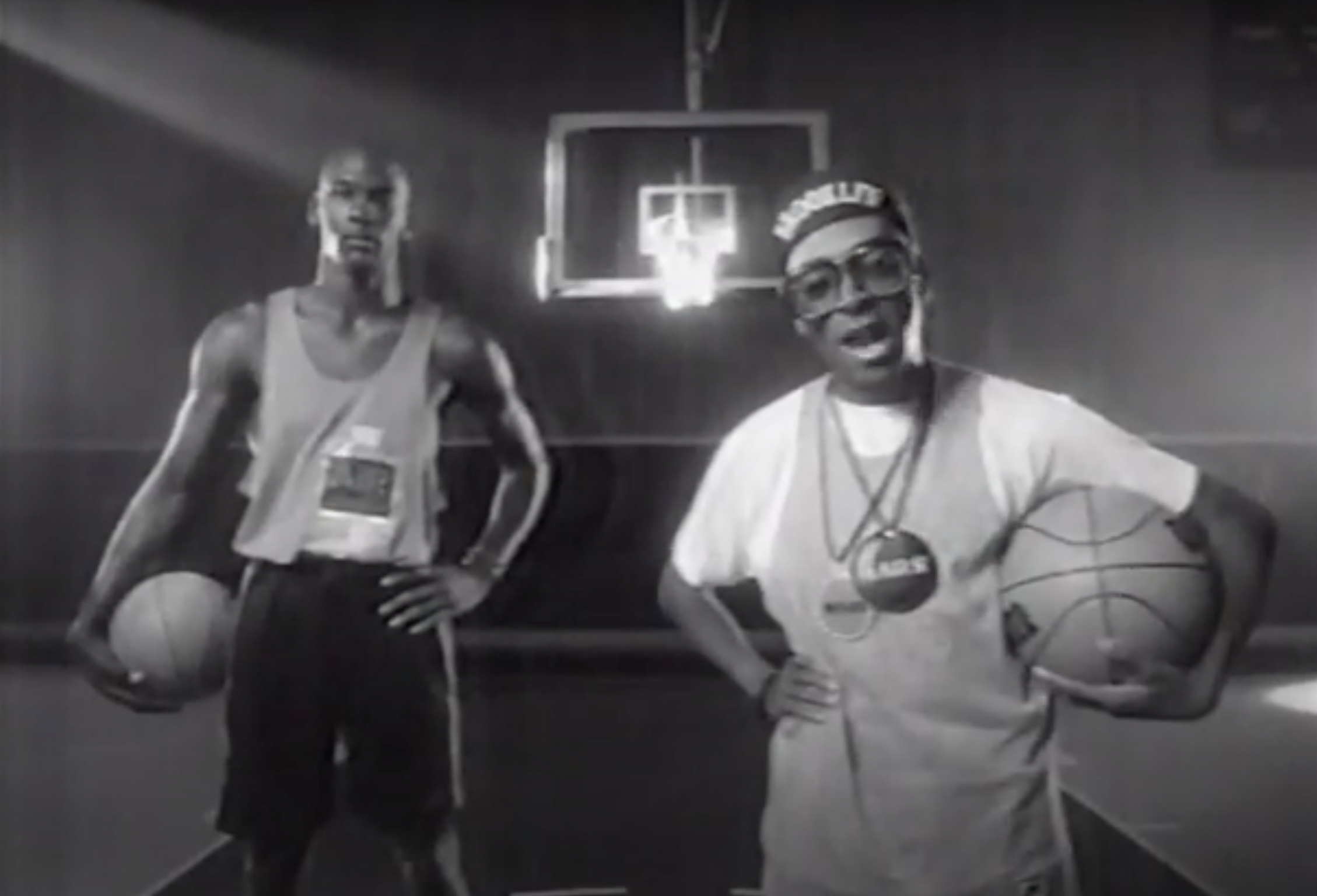

With the script having garnered the right people’s approval, the shooting began. Jordan was clearly the alpha male with nothing to prove. “He was immediately friendly,” Lee wrote, “but in a challenging kind of way.” The first time the two met, Jordan said, “Spike Lee.” Lee interpreted that sparse greeting as a challenge. Show me what you’ve got. Jordan knew. About a year before the commercials aired, Knight and Jordan were out at dinner, when Jordan unleashed “Pleasebaby- pleasebabypleasebabybabybabyplease.” He said it another two or three times.

“What the hell is that?” Knight asked.

That was Mars Blackmon’s signature line from She’s Gotta Have It, which Jordan loved.*

Davenport witnessed Lee and Jordan grow comfortable with each other. There were no problems. Lee was not like most commercial di- rectors, men with outsize egos. He worked with a small, diverse crew devoid of hangers-on and company men. Like She’s Gotta Have It, the shoot was a low-tech, simple affair. It worked.

“We knew with the first shot we had something magical,” Riswold said.

*Knight said he relayed Jordan’s love of the film to Weiden + Kennedy, who then talked to Jordan and created the spot.

Davenport thought the first spot, which ran in 1988, was perfect. Mars Blackmon came across as authentic and believable, Davenport said. Mars was the proxy for every basketball fan—“and a better actor,” Riswold said. The motormouth brought Jordan down to earth, made him human, a perfect retort to the otherworldly athleticism. Riswold’s script took the burden off Jordan to act. Jordan’s assignment was to express disapproval or approval, have fun, and dunk. He could joke at his untouchable image without risking anything. Jordan and Lee, Riswold thought, made each other look good.

“In order to have effective advertising rather than traditional advertising, you really need to know who the subject was,” Knight said. “And so we want to know who Michael was, and Michael really liked this character, so what we were showing was that something he really be- lieved in. And that’s sort of been the cornerstone ever since.”

“Nike was very fortunate to have had Wieden + Kennedy as its ad agency, because Wieden understood pop culture, it understood Nike, and it understood Nike’s messaging, and it understood how to get to that part of the athlete that the consumer wasn’t seeing,” Nike’s Mark Thomashow said.

Riswold saw the footage from the shoot. When everything was put together, he entered Dan Wieden’s office.

“Wieden,” Riswold said, “all I can tell you is, we’re blessed.”