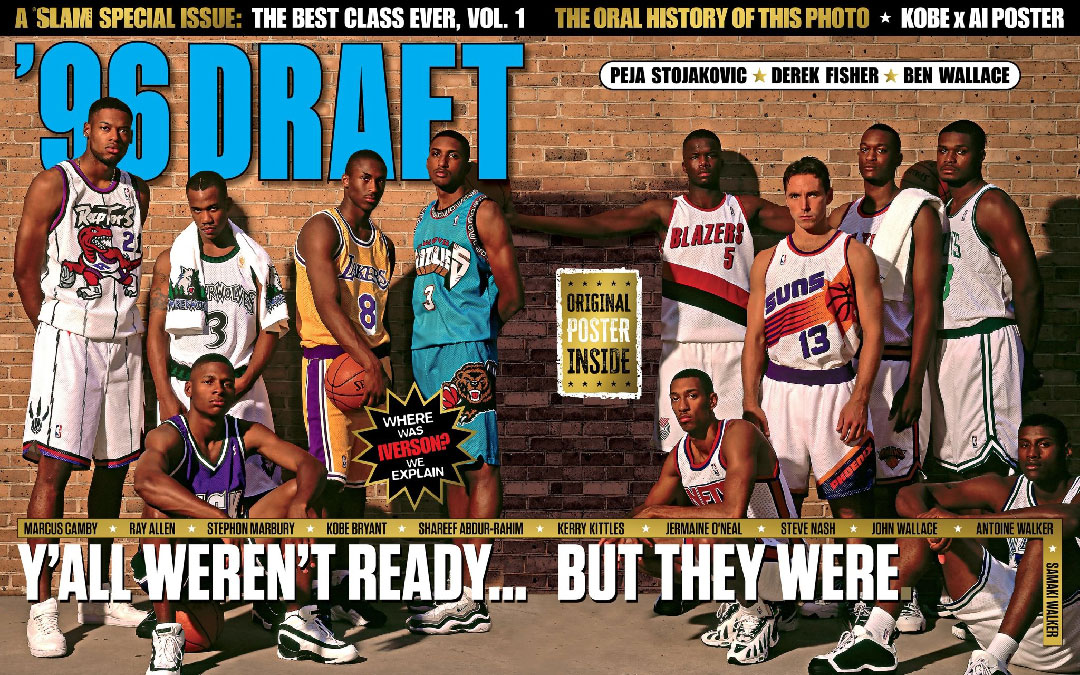

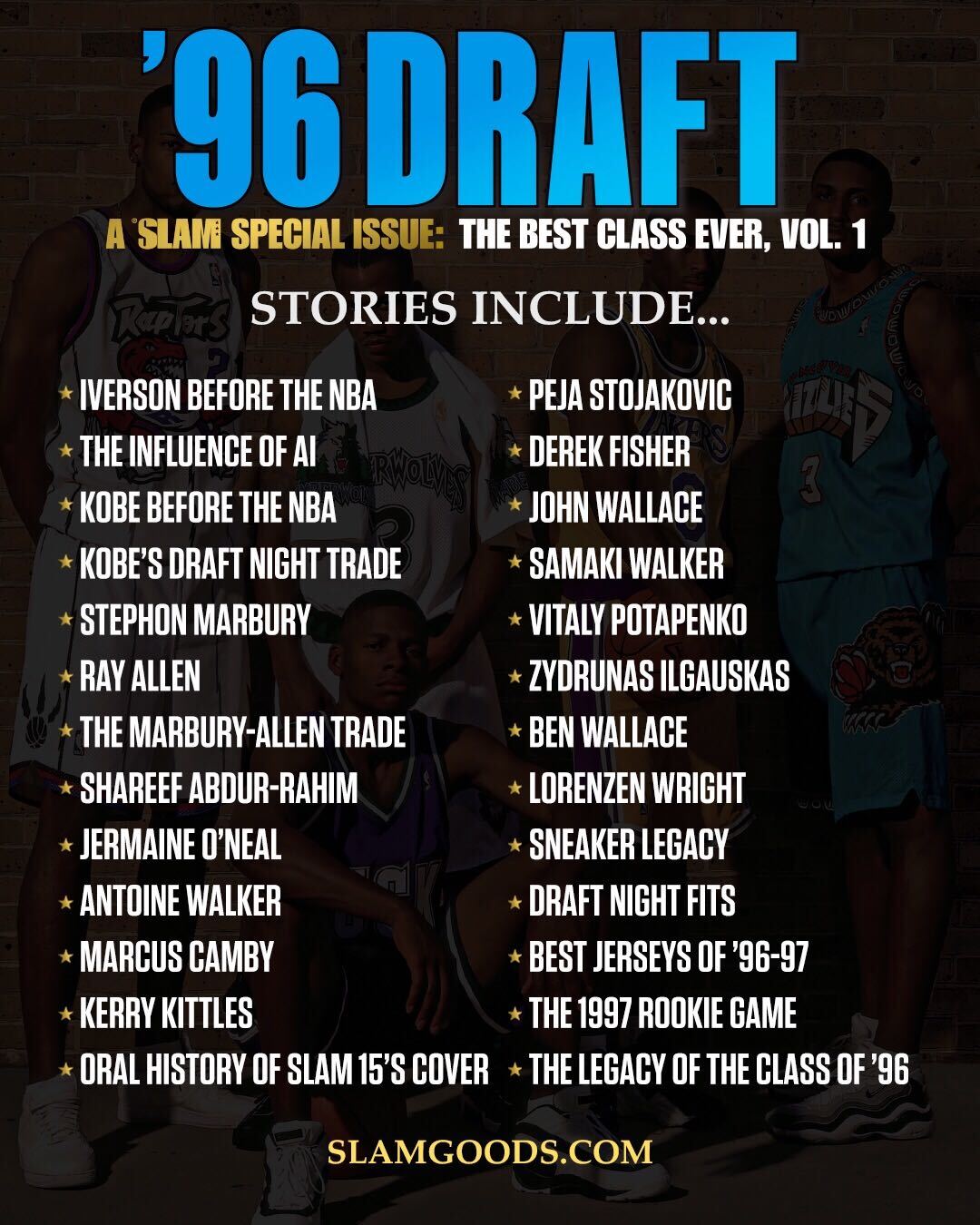

GRAB YOUR COPY OF SLAM PRESENTS ’96 DRAFT

He might have been in the twilight of his career, but 36-year-old Dominique Wilkins could still play. During the ’95-96 season, the nine-time NBA All-Star went to Athens to hoop for the Greek powerhouse Panathinaikos.

Wilkins would go on to lead the team to the coveted EuroLeague championship that season. But it was during Greek League play that an 18-year-old forward by the name of Petros Kinis caught his attention. Standing a sturdy 6-9, he played with a confidence and swagger that belied his years.

His shot, although unconventional, was quick and pure and always seemed to find the bottom of the net. Whether he was moving off screens, spotting up or getting open in transition, his shot was almost impossible to contest.

“I was like, Whoa, this kid can play! He was a helluva shooter,” Wilkins recalls. “He was young, though, but you could see that he had potential.”

Long before he became a Greek citizen (with a Hellenized name and surname, the aforementioned Petros Kinis), before he signed with PAOK, Peja Stojakovic had dreams of making it to the NBA. Not only because he grew up idolizing the greats, including Nique, but to help provide for his refugee family. When the Yugoslav Wars broke out in 1991, 13-year-old Peja fled his town of Pozega in east Croatia along with his parents and older brother.

They had lost everything—their house, business, possessions—and struggled to make ends meet in their new home of Belgrade. But now living in the basketball mecca of Southeastern Europe, Peja quickly found out that he had a talent for the game. Standing 6-4 at age 14, Peja made the tryout for Red Star Belgrade’s junior team and went from playing twice a week to twice a day.

“I just kind of stopped fooling around with basketball and started to take it a little more seriously,” Peja said in SLAM 59. “The coaches who saw me kept encouraging me, saying I was a natural and all that. So I started playing a lot.”

GRAB YOUR COPY OF SLAM PRESENTS ’96 DRAFT

A year later, Stojakovic began playing with Red Star’s senior team. During his first pro season in ’92-93, Peja played sparingly over 39 contests but helped Red Star win its 13th national championship (and first in 21 years). By the age of 15, Peja was making good money playing basketball. Being able to provide for his family drove him to work even harder and maximize his talents.

Stojakovic turned down a contract with Red Star for a five-year deal with PAOK in the Greek League. The decision was a surprise to some, but it afforded his family the opportunity to get out of war-torn Yugoslavia during a deadly conflict that would eventually claim over 130,000 lives.

After waiting a year to obtain his Greek citizenship, Peja was activated during the ’94-95 season. In his first full season in Greece, Peja helped PAOK win the Greek Cup, placing himself firmly on the radar of NBA front offices.

“Everybody in Europe knew who Peja was, and even here [in the States] I knew,” said Vlade Divac, who was playing with the Lakers at the time, in SLAM 59. “I knew that as a young guy he had tremendous skills, and he was going to get better the more polished he got.”

The next season, PAOK signed American big men Lawrence Funderburke and Dean Garrett. Kings GM Geoff Petrie, who had drafted Funderburke in the second round a year earlier, was keeping close tabs on the 18-year-old Serbian scorer.

“I remember when the Kings were recruiting Peja, they asked me what I think about him—his work ethic, his practice habits, etc,” Funderburke says. “And I said, This kid is going to be a special player. Not only does he work hard, but he wants to be great. He doesn’t just want to play in the NBA, he wants to be a great player in the NBA.”

Divac, the late Drazen Petrovic, Toni Kukoc and Dino Radja had already proved that players from Stojakovic’s region could make an impact in the NBA. While known for being highly skilled, European players—unjustly or justly—were labeled as “soft” in NBA circles at the time.

The Greek League featured a number of former NBA stars, including Wilkins, Xavier McDaniel and Rolando Blackman, all of whom were considered anything but soft. Whenever Peja got the chance to match up against an American player, he never backed down from the challenge.

“Peja never backed down from anybody. If it was somebody that was an American, he was ready to go,” Garrett says. “He was always ready to go against that person because he looked at Americans as being the best.”

From the time he was young, Stojakovic would study film of Michael Jordan and other greats. He loved the NBA game. He undoubtedly had a lot of respect for a player like Wilkins, who had a Hall of Fame résumé. But when it was time to match up with the legend, Peja took the challenge head-on.

“[Dominique was] still able to run and jump, still had his shot, but he couldn’t keep up with Peja,” Funderburke says. “I remember his facial expressions, too, like, This kid right here can play. Sometimes you don’t have to say anything, it’s just the body language.”

“I can remember Dominique during the game asking me who this kid was,” Garrett says. “Who is this kid? And I was like, Hey, this guy is pretty good.”

“He showed a lot of respect, but yeah, he did [go at me],” Wilkins remembers. “That’s the thing about real competitors. You might idolize a certain person, but at the end of the day when it’s all said and done, hey, we’re out here trying to win, we’re out here competing. So yeah, he competed.”

“He just had a lot of confidence,” Garrett says. “He shot the ball with confidence during the games, and pretty soon you start looking at this kid and you’re like, Man, he’s probably the best player on this team.” The NBA rumblings were getting louder and louder. Peja’s dream was about to become one step closer to reality.

“I knew, the way things were going, that I might have a chance to play in the NBA,” Peja said in 2002. “I knew a little about it, and of course it was a dream. But I didn’t know when it would happen.”

***

Samaki Walker. Erick Dampier. Todd Fuller. Vitaly Potapenko. Then at pick No. 13, the Hornets selected a 17-year-old kid from Lower Merion High School named Kobe Bryant. With the draft lottery finished, Peja Stojakovic was still sitting in the green room, waiting for his name to be called. Outside of the NBA war rooms that night, very few Americans knew who Peja was, much less could pronounce his name.

The pundits were pushing for the Kings to select John Wallace, who led Syracuse to the NCAA championship game a couple months prior. They touted Wallace as a known talent who could contribute in the NBA immediately. But Petrie had his mind made up on selecting the rising star from Europe. The Kings had worked out Stojakovic twice in Sacramento before the draft.

When commissioner David Stern announced Stojakovic’s name as the No. 14 overall pick, Kings fans and players alike were scratching their heads.

“We didn’t have social media back then. We couldn’t go on the computer and pull up a game and watch him play to have a feel for what he was,” says Corliss Williamson, who had just finished his rookie season with the Kings. “So in the back of your mind, you’re like, OK, what are we doing?”

Not exactly helping matters, Peja couldn’t get his hat to fit his head correctly as he walked up nervously to shake the commissioner’s hand. While he spoke good English, Peja fumbled through an interview with Craig Sager as he tried to keep his composure. And then there was word that he wouldn’t be coming over to the NBA immediately.

He couldn’t get out of his Greek contract, and Peja’s father also felt that he needed more seasoning overseas before joining the NBA. Peja, however, insisted that he wanted to play for the Kings right away.

“The owner kept making problems for me—he didn’t want any money, he just wanted me to keep playing for him,” Peja has said. “It was very frustrating for me, because I felt I was ready.”

Stuck with no other option but to play out the remaining two years on his contract, Stojakovic returned to Greece and thrived as the No. 1 option for a very good PAOK team. During the 1997-98 season, Peja scored 23.9 points per game and won Greek League MVP. He drilled a memorable three-pointer at the buzzer to defeat reigning Greek League champion Olympiacos. And he would go on to lead the EuroLeague in scoring.

Duty fulfilled to his team in Greece, Peja finally arrived in Sacramento in 1998 for a lockout-shortened rookie season. The Kings hadn’t enjoyed a winning season in 15 years, but the team had overhauled the roster, bringing in Stojakovic, Divac and Chris Webber, drafting Jason Williams and hiring Rick Adelman as head coach.

Things began to click almost immediately. “The Greatest Show on Earth” became the talk of the League, featuring a motion-heavy offense that played at a supercharged pace. But Stojakovic, who had been the man in Europe, was relegated to a bench role his first two seasons in Sacramento.

Leaning on his fellow countryman Divac for support, Peja stayed confident and made the most of his minutes. He relied on the work ethic that helped bring him to the NBA and bring his family to America. He stayed in the gym—always the first to arrive and last to leave. Quickly, it became clear that Peja was the team’s best offensive weapon and needed more playing time.

“We were playing the same position, so I’m fighting to save my job,” says Williamson with a laugh. “But I could tell that this guy was going to be special, and I was happy to have him as a teammate.”

Prior to the ’00-01 season, Petrie would trade Williamson to Toronto for Doug Christie, opening up a full-time starter role for Stojakovic. He would start every game he played that season, averaging 20.4 points and finishing second in Most Improved Player voting.

From ’01-04, Stojakovic was one of the most potent offensive players in the League. He became the only player during that span to average at least 19 points on 59 true shooting percentage for three straight seasons (no other player did it more than once). He became the first European-born player to win an All-Star competition—winning the Three-Point Contest not once, but twice. He was named an All-Star three straight seasons, and finished top-four in MVP voting in 2003-04.

He went on to finish his career as a champion with the Dallas Mavericks in 2011. Not only was Peja able to achieve his dream of playing in the NBA, he surpassed all expectations once he got there. He helped take his family from a war-torn country to a life of prosperity. And his jersey now hangs in the rafters of the Golden 1 Center.

Not bad for a kid by the name of Petros Kinis.

—

GRAB YOUR COPY OF SLAM PRESENTS ’96 DRAFT

Ryne Nelson is a Senior Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @slaman10.

Photos via Getty