Led by Guest Editor Carmelo Anthony, SLAM’s new magazine focuses on social justice and activism as seen through the lens of basketball. 100 percent of proceeds will be donated to charities supporting issues impacting the Black community. Grab your copy here.

—

As told to Isis Haywood:

Don’t think of me as special for what I’ve been through. A lot of African American players and people have been through the same things that I have, but anyone can affect change.

I experienced two events when I was younger that frustrated me at the time, made me feel less than any other citizen, and I did not fully understand why they could occur. These events stayed with me for a long time, but I eventually found avenues to make change the best way that I knew how.

The first event happened when I was in high school in Indianapolis. I attended Crispus Attucks HS, which was an all-African American school. Crispus Attucks was known as the first African American person to be killed in the Boston Massacre uprising for demonstrating against the British.

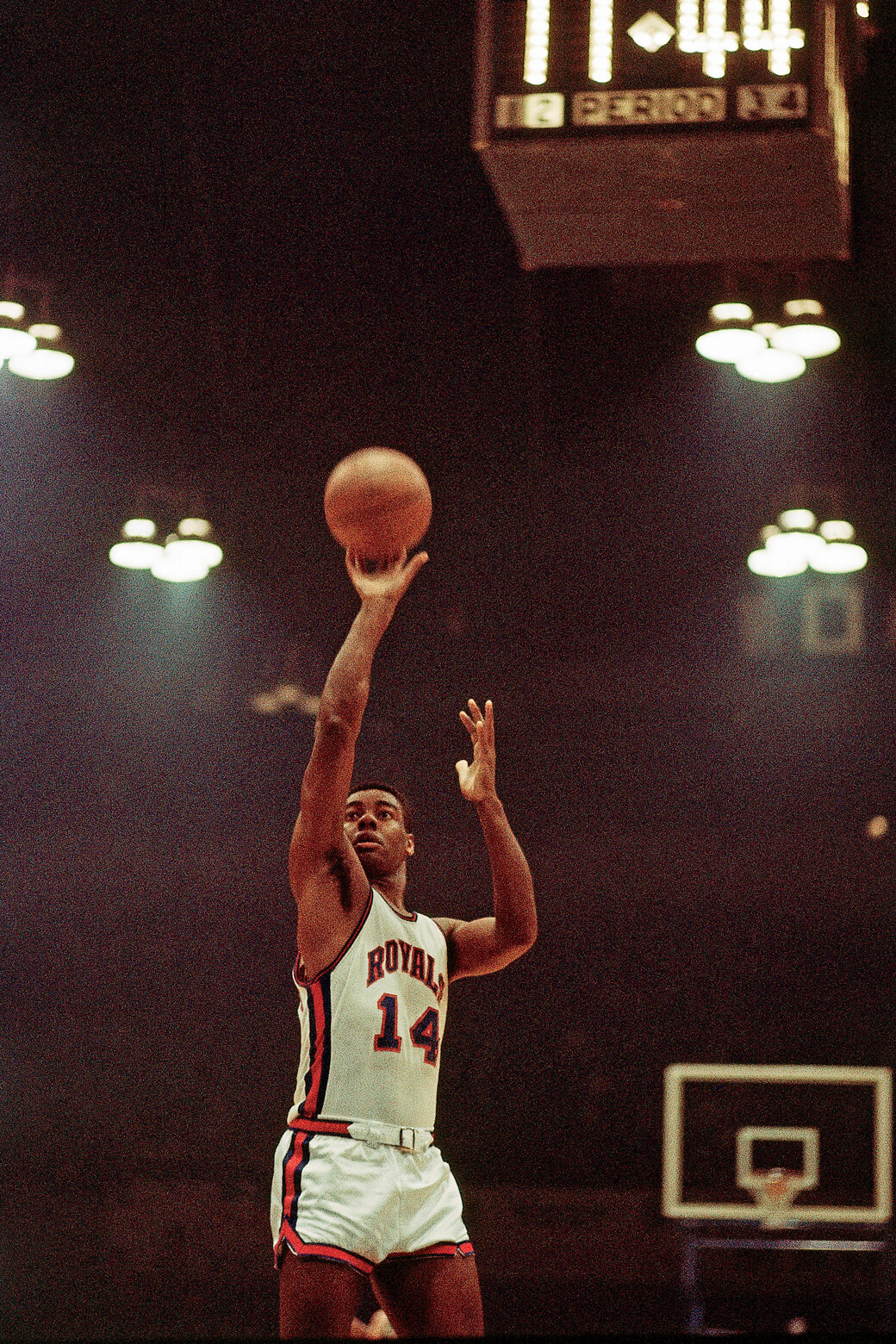

At that time, during the 1950s in Indianapolis, high school basketball was mostly segregated, and Crispus Attucks did not compete against predominately white schools until the charter for the high schools was enforced so that everybody got to play in the city tournament. To some people’s surprise, an all-African American high school won the state championship in 1955. We were all just excited kids, getting to enjoy something that we were good at, and won statewide recognition. Of course, as a teenager, we did not know at the time, but we were the first all-African American team in the United States to win a championship like that and the first team from the city of Indianapolis to win a state championship.

I was so naïve back then. Similar to the predominately white schools that won in previous years, I thought that the city would have a parade that would take us from the Fieldhouse about 50 blocks downtown and let us off at Monument Circle at the center of Indianapolis. Usually, teams would be able to celebrate around the Circle all night until they got ready to go home. The winning Crispus Attucks team, however, was not allowed to celebrate in this tradition. We did get to travel downtown, but we could not celebrate at the Circle. Instead, the parade organizers went around the Circle one time, took us away from the site to a mostly African American neighborhood called Northwestern Park, and we celebrated with a bonfire there. We had no idea what was going to happen when we got on the firetruck. I was just stunned and started to think, Why did they do this to us? I just could not believe it at the time that you could be treated as less than any other high school champion just because we were Black.

The Monument Circle incident did not dull our enthusiasm for basketball or our ability to play. We were just as excited to go undefeated the next season in 1956 and win another state championship. This time, I did not want to take part in a celebration at Northwestern Park and stayed home, because it was not offered to every other city champion. I was a really shy person in high school and didn’t say too much. I didn’t know how to express my frustration with something that was important to me as a teenager. The only opportunity to express how I felt around that time was when some officials asked me during my college years to come back to Indianapolis. I refused and said, “No, I don’t want to come back because you treated us terribly.” Several decades later, in 2015, the city of Indianapolis gave the remaining members of the 1955 Crispus Attucks team the parade and celebration at Monument Circle that we had previously been denied. And I appreciated the chance for our team to celebrate as others had.

The second incident that had a tremendous impact on my life occurred when I was attending the University of Cincinnati. I was eligible to play varsity as a sophomore (freshmen could not play varsity at that time) and had an away game in Houston, TX. After arriving at the hotel with the rest of the team and coaches, who were all white, I was told, “You have to leave.” I said, “Where are we going?” I thought the whole team had to leave. No coach or representative from the University of Cincinnati told me that I would not be able to stay at the Shamrock Hilton Hotel because I was African American. I was taken to Texas Southern University, where I met their African American basketball coach who arranged for me to sleep in a dorm room.

I was so upset but didn’t know what to do. At the game, I didn’t take a single shot during warm-ups. I just stood at half-court while people were literally throwing things at me. It was one of the roughest games in which I ever played, but I had learned to play against very physical opponents back in Indianapolis when I used to tag along with my older brothers to pick-up games. I got through the game emotionally by channeling my frustration into effective basketball on the court. But still being shy, frustrated and not knowing what to say, I refused to do any interviews after the game.

Upon returning to Cincinnati, I asked for a meeting with the coach. After asking, “Why am I being treated like this?” he claimed that he didn’t know that was going to happen down in Houston. I responded by not participating in any banquets or alumni events. I led the nation in scoring for three years in a row, was the NCAA Basketball Player of the Year and made the Dean’s List, thanks to the wonderful preparation from my teachers at Crispus Attucks. My contribution to progressive change at that time was being the right college student-athlete to forge paths for others.

I became involved with the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), the union for the players, when I joined the League. At first, I was merely a member and paid my dues. It was important for me to participate in some way because I thought that the NBPA was a way to try to get improvements for players. I had no idea how powerful the organization was going to become, but I believed it was a vehicle for some type of change. The NBPA was the first organized union in sports.

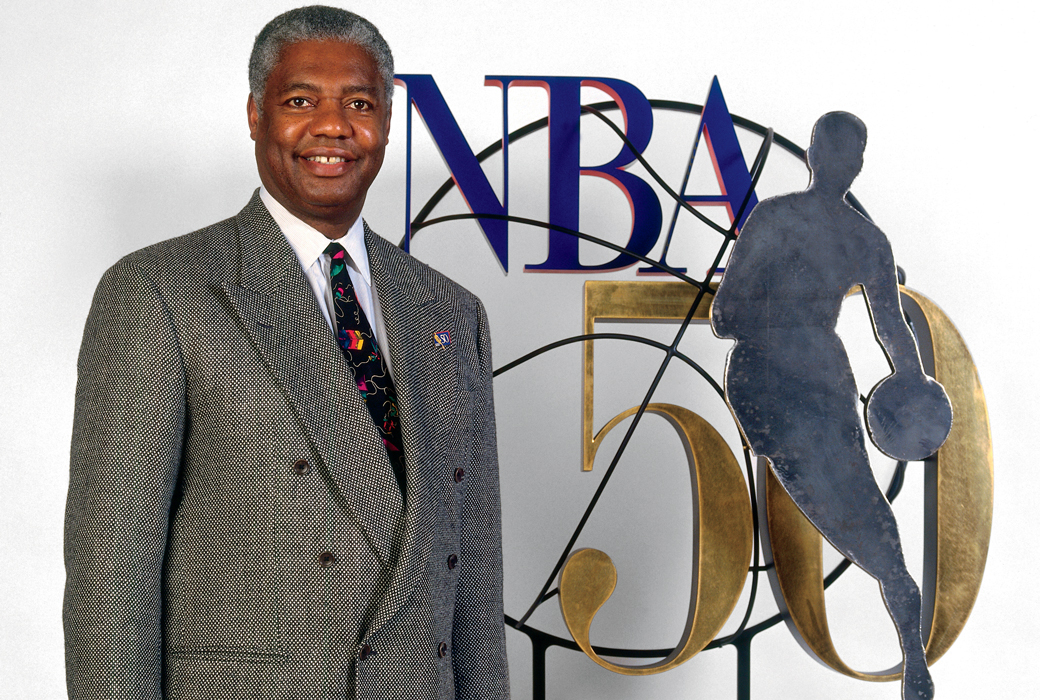

I ended up in this position of power as head of the NBPA. Jack Twyman, one of the original leaders of the union and a teammate on the Cincinnati Royals, was going to retire in about a year and also needed time to care for Maurice Stokes, a teammate of his who was paralyzed. He felt, I believe, that I would be an effective leader because of my ability on the court, meaning that the owners would not retaliate. You see, some other team representatives for the NBPA were, in fact, retaliated against by owners by being traded. In some cases, you did put your career on the line by being a player representative to the NBPA. When I took this role, I became the first African American president of any national sports or entertainment labor union and was also the longest-serving president—for nine years until my retirement in 1974.

At that time when I became the president, players had very few rights. We didn’t have a trainer on the road. We all flew coach. We didn’t have an orthopedic doctor at the game in case you got hurt, and we were limited to $8 a day for meal money. And as for contracts, few were guaranteed. This meant that an owner could end your stay with a team for the smallest of reasons and possibly never allow you to play professional basketball again. They had the power to do that. Moreover, the owners had perpetual rights over players. There was no free agency.

The NBPA fought for what we believed was right and fair. We fought to improve all of the situations that I just described. When the American Basketball Association was formed in 1967 and there were talks of a merger with the NBA, the NBPA filed the first anti-trust suit in professional sports in 1970. We were able to get certified for class action and sued to improve salaries and working conditions. What was important was for each player to have the right to earn according to his ability in a fair market. We needed to end the reserve clause to allow a player to play out his contract and end some other practices limiting player movement in our fight for free agency.

I did not know if we would be successful. I thought our chances were 50-50. The owners had a lot of power and political influence and tried at every turn to stop us. They asked for Congress to pass a special exemption for them regarding their anti-trust status. However, we were fighting for what was right, and I found a voice testifying in front of Congress about what the NBPA thought was just. Also, new teams with new owners were entering the League that perhaps wanted things to be more fair so that they could also compete. After a long six-year legal battle, the NBPA won in 1976 after the reserve clause was ruled illegal and replaced with an option clause, allowing players to change teams without the original team retaining rights. The historic settlement became known as the Oscar Robertson Rule. The ruling led to free agency in other professional sports and a new era of growth for nearly all sports. Despite the personal and professional risk of taking on the sports establishment, I would have done it again in a heartbeat because basketball players, athletes and African Americans should be treated as any other person in American life.

What I realized as I grew up professionally and personally is that you have to fight for just causes and speak up for yourself and others. I hope that people will do so this November.

—

100 percent of proceeds from SLAM’s new issue will be donated to charities supporting issues impacting the Black community. Grab your copy here.

Photos via Getty.