Led by Guest Editor Carmelo Anthony, SLAM’s new magazine (below) focuses on social justice and activism as seen through the lens of basketball. 100 percent of proceeds will be donated to the Social Change Fund. Grab your copy here.

—

I grew up in a small town, roughly five blocks from the Gulf of Mexico. But we were on the other side of the cut. We were in the ghetto.

I grew up in a single-parent home. My mother raised me with two of my brothers. She had the equivalent of an eighth-grade public education and was our sole provider yet provided for us in ways that astound me to this day. How she did it—making it all work and distracting us from the devastation of it all—is nothing short of amazing.

I grew up never knowing who my father was. As a child, that was something that periodically disturbed me—just not knowing that information. Oftentimes growing up, you’re looking for that male figure to help take the load off you. But, for me, it never came.

Growing up in Gulfport, MS, I remember walking to the beach one day. I can vividly remember, as if it was yesterday, watching the KKK casually marching down the beach; I couldn’t help but wonder who was under those white hoods and if I knew them. Even at that time, they signified something evil.

As a young man, I struggled with my identity, especially when it came to academics and feeling like I wasn’t smart. So, I grew up with an inferiority complex and not having confidence in my abilities.

But I found basketball. Basketball was something I felt I could do and so I gravitated toward it. And in some crazy way, part of why I trained so hard was because I was hoping that if I became super great and well-known, then whoever this man was—my father—would re-enter my life. But it never happened.

I began waking up at 4 o’clock in the morning because I knew I had to give myself the best opportunity to succeed if I wanted to get my family out of the ghetto. I didn’t see a future for myself academically. I didn’t know statistically at that age that I had a better chance of becoming a doctor or a lawyer than a basketball player. Even if I did, I probably wouldn’t have pursued it because my mother had an eighth-grade education and so we didn’t grow up with books in our house or with the push for critical-thinking skills and problem-solving. It became an issue of life or death for me—getting up early in the morning and training like my life was literally on the line. At 9 or 10, that was my mindset.

Growing up with Tourette syndrome, not knowing that it was Tourette syndrome, I was misdiagnosed all the way up to the 11th grade. You get taken to the doctor and you’re told that you got habits that come and go. To this day, I don’t think there is any medical diagnosis where you give a child a pill and the medical diagnosis is “habits.” My mother would take me in and they would prescribe me these huge pills. I took them to the point that I would gag and eventually I just started hiding them in a cinder block in the part of the house that wasn’t finished.

As a child, not being able to keep your body still is tough. You’re twitching and you’re trying to control your body while it’s forcing you to do things you don’t necessarily want to do. You go into school and you’re trying to listen to a teacher while at the same time trying to stay still. I can’t even hear what the teacher is saying because I’m so busy trying to stay still. And then children can be cold-blooded; they see a potential flaw in you and they’re going to take you till no end.

When I went to LSU, from a social and academic standpoint, it was brutal.

Having Tourette syndrome but then also having this notoriety as an athlete on campus, I would still try to keep it under wraps. I would try to camouflage it as much as possible. Socially, that became challenging.

Academically, my first day, they brought me into this class—I can’t remember what it was called but it’s like they were assessing my knowledge to see where to place me. As a child, I could read well and I could spell well but my comprehension skills were terrible. I memorized my way through school. So at LSU they put me in this class and they had me reading something. If they would have left it at that, they would have probably thought I was super intelligent. But then they go, “What does this word mean?” I don’t know. They said, “Well, what is this?” I don’t know. They then said, “Well, what did you get out of the story?” I don’t know. I went through it. I could write and spell words, but in terms of defining them, I couldn’t.

They ended up putting me in a remedial reading class. A lot of people didn’t know. You look at this guy who is breaking records and is on the cover of Sports Illustrated, but he’s at a level where he can’t even identify the moral of a story or describe a concept. When I went through that, it took me to another level. I was having an identity crisis.

But that experience made me want to study hard. After games sometimes, we would be up at 2 or 3 in the morning with a tutor to be able to turn in my assignments. It was a challenge.

Along the way, I found Islam. It started for me at LSU when head coach Dale Brown handed me the autobiography of Malcolm X. I had never heard of Malcolm at the time. The day before I left LSU is when he handed me that book. He would always give us quotes and things to read because he’s an avid reader.

That’s when I was like, Wow, this is an extraordinary individual! So, when I got drafted by the Denver Nuggets, even though I wasn’t saying anything publicly, Malcolm’s life story and all of what he stood for was in my head. I began to have questions about my own faith, about my own existence and about how I wanted my life to speak for itself when I would be dead and gone. I wanted to be recognized as an athlete. But then I wanted to be recognized as much more.

I did some soul searching and it just so happens that I met a guy named Marc James out of New York. I was still a Christian at the time. I grew up as a Baptist, but he was a Catholic priest.

One day, Islam came up in conversation. We were interested in learning more. We met this brother and went to pick up the Quran. We went back to my house and two or three pages in, I looked across the table at him and was like, I don’t know about you, but I’m going to be a Muslim. And he said, “Well, I’m going to be a Muslim, too.”

I started going to the mosque. Every time I picked up the Quran, it never ceased to satisfy my curiosity. That led to me embracing it.

In the NBA, you travel a lot. And once people knew I became a Muslim, I don’t know how people would find out what hotels we were staying in, but I’d be in the lobby and hear people say, “As-salamu Alaykum!”

I’m a people’s person. I had a habit of inviting people up to the room. All you had to do to have access to my room was to tell me “As-salamu Alaykum.” You could’ve been a criminal or anything. But it became a tradition on the road. Everywhere I went, people would meet me. And as a habit of mine, I would invite them upstairs to the room even after games, and we would stay up until 3 or 4 in the morning if we didn’t have to leave for the next city. From professionals to students, they’d introduce me to concepts and things I had never heard of—history, politics, sociology and religion. Then Ramadan came, and we were encouraged to read through the entire Quran during Ramadan. I wasn’t an avid reader so that was my first time ever finishing a whole book—the Quran.

My curiosity grew and I started having dialogue and reading more. On the road, it became these private study groups for me. That education I got from city to city was the best education I ever got and was the best thing that could ever happen to me. It took me to a place where I was like, I got to make a choice. There’s no such thing as being neutral. I have to take positions in life.

And those things led to the 1995-96 season.

The more I began to read, study and learn about the system, the more I realized things weren’t right. After learning all these things, now I’m pissed off. There’s a system behind all of this that I’m reading about.

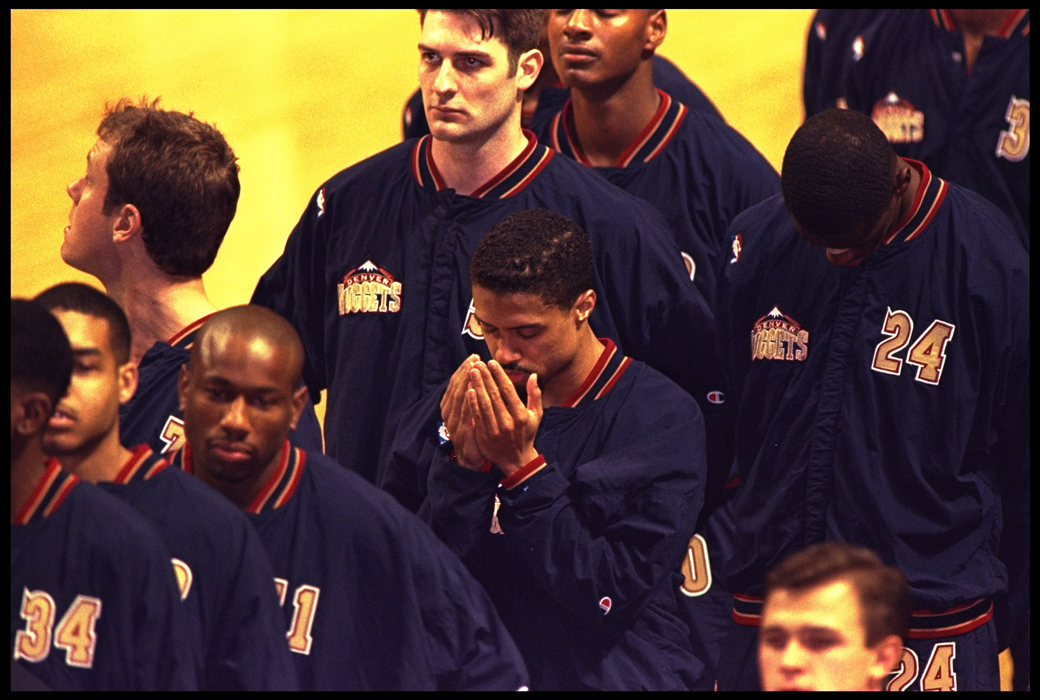

And so, I decided to stop standing for the national anthem.

I had been doing it for about four months the previous year before the media noticed and said something. I knew in my heart I was no longer for this—the systematic oppression.

I wasn’t out there promoting it but then someone in the media realized that I had not been standing. He asked me about it and then he published the story.

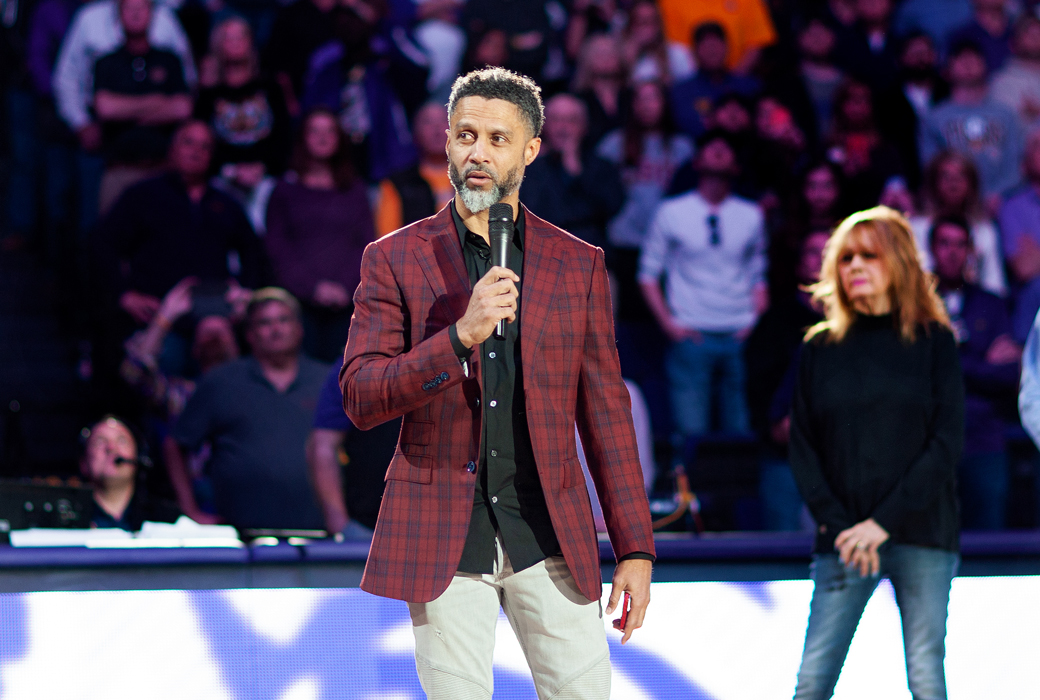

The next day, we were playing Shaquille O’Neal and the Orlando Magic. After shootaround, there were a bunch of reporters. The very first question was, “What do you think about the flag?” I spoke my conscious and I haven’t looked back since. It opened the floodgates.

After shootaround, I went home before coming back for the game. I got to the locker room and before I could take my clothes off, I’m told that Bernie Bickerstaff, our head coach at the time, wanted to speak with me. I go to the office and he says, “We got a call from the League and they’re going to suspend you if you don’t stand.” I said, I can’t do it. And so, I was suspended.

He then said, “Well, there’s a couple of guys from the NBA office that want to talk to you.” We got on the phone. It wasn’t David Stern. I never spoke with David Stern—even though the media said that I went up there to meet him in New York. That was a lie. On the phone, I said, “This was my decision. This is what I have to do. You do what you have to do.”

They didn’t even want me on the premises. So I had to leave the arena before the game.

After, I ended up talking to a mentor of mine. He told me a story about the Prophet once standing when a Jewish funeral procession was passing by. If it wasn’t for that story, my career would’ve been over. I was prepared to not come back.

He told me, “If you decide to not come back, that’s a noble decision and you’re not wrong for doing that at all. But if you decide to come back, and not for their cause but for a higher cause, then that’s also not wrong. So, you can come back and stand for those who are oppressed, you can pray for those, you can take positions for those, you can use your platform.”

When he told me that, I was so angry at him because I knew no matter what I did and what position I took, people would say, “Oh, he compromised!”

As soon as I came back, reporters would come up to me and say, “Oh, you made a compromise!”

I would tell them, No, I still feel the same way. I still feel there’s systemic oppression. I still feel the flag is this way. I wanted to make a point that my outlook wasn’t going to change. But this is the route I’m going to take. I will stand but with my head down in prayer during the anthem.

At the end of that season, I got traded. I saw my minutes drop. I saw the interview requests drop. And by 1998, teams weren’t looking to give me any offers. There was actually only one team that gave me an offer, but I felt like it was an insulting offer because I was still in my prime.

It became obvious to me that me not playing anymore was a setup. I was trying not to be the type saying, Oh, they’re doing me wrong! After games, though, reporters were asking me why I wasn’t playing. It became obvious to everyone.

It felt like they were saying, OK, he just did this. He’s still in his prime. But we’re not going to show him. We’re not going to mention him. It almost felt like they were trying to erase my playing memory. It was the same playbook they used with Colin Kaepernick. And so, I ended up going to play in Turkey.

It wasn’t something that I didn’t understand, especially as a young Black man. There were death threats and the burning down of my house in Mississippi in 2001. When we were building it, I remember coming there one morning and seeing these huge tire tracks. Someone had run their vehicle into the garage, tearing the garage down, and then they came back out through it. Then another time I came back and saw there was the Ku Klux Klan initials written on there.

Then one day, it was like 4 o’clock in the morning, I was asleep and the phone rang. It was a sister in the community calling and saying, “Mahmoud, turn on the television! Your house is burning!” I turn on the TV and I’m looking at images of the house on fire. I drove down there. I told the community to come down. I put down targets, brought our guns and started shooting on the property. I was basically saying at the time, It is what it is, but I’m not going anywhere.

I was trying to buy property there and section it off and then sell so that other people could buy property and we could develop a community because we had a huge lake and huge farm land. We were like, Let’s build and establish our own community. It was 53 acres.

But then I thought about it. I didn’t feel comfortable leaving my children and my family there, and so that’s what made me sell it. Now, if it was just me alone, it’d be a different story.

Looking back at everything, I’d rather live and die with a free conscience.

This is definitely a critical time in our history, and I just pray that we don’t take our foot off the gas. The young people are not having it. Everybody has to get on board with them.

—

100 percent of proceeds from SLAM’s new issue will be donated to the Social Change Fund. Grab your copy here.

Photos via Getty.