History gets a bad rap. It’s easy to think of history from the perspective of a student in a classroom, nothing more than a collection of boring stories and irrelevant facts. But that misses the point. History is really just another word for perspective. History is a tool. History is useful as hell.

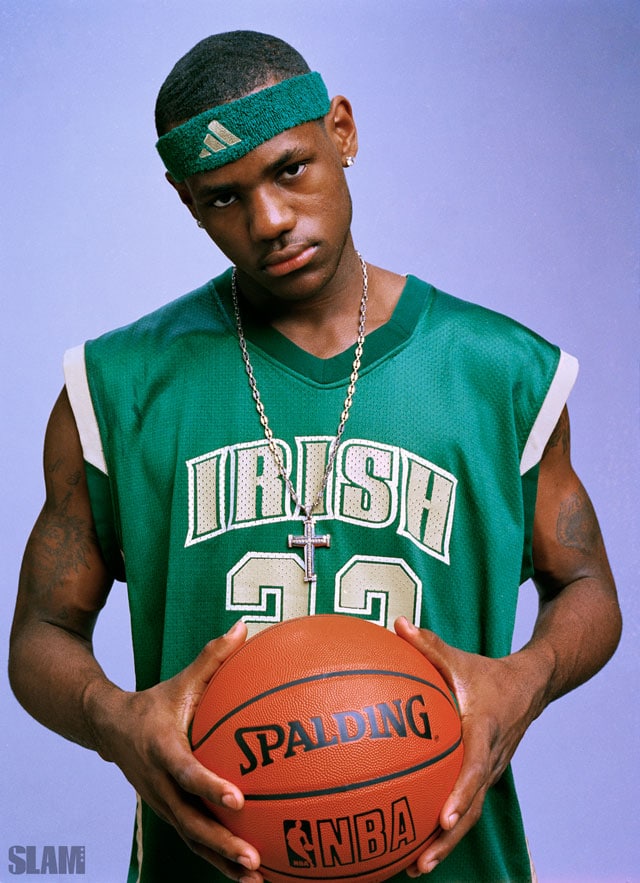

Where SLAM and LeBron James are concerned, history is something else: essential. We cannot talk or think about this 32-year-old, four-time NBA MVP without thinking of the 16-year-old high school sophomore we met and wrote about before almost anyone outside of northeast Ohio knew who he was. There were exceptions, of course—even then, the college coaches, potential agents and sneaker company reps were already in the mix—but for the most part, LeBron was still an unknown.

That changed, for us, in the spring of 2001. That was when our history with LeBron James began. Everything since—the numbers and trophies and championship rings, the growing political and social justice impact, the staggering cultural and economic influence that reaches from his hard-nosed hometown to Hollywood and beyond—we are obliged to view through the lens of that early access. In the 16 years since, we’ve had a better seat than just about anyone to watch LeBron evolve and mature—and more times than we can count, we’ve been lucky enough to get behind the scenes with him and his people, to better grasp his work ethic and motivation, and the support system that has helped him defy expectations on and off the court.

So, pardon our habit of checking the rearview where the King is concerned. We enjoy the nostalgia, no doubt, but it’s deeper than that. No great journey can be understood without an appreciation for its origins. LeBron has reached a level of fame that makes his story accessible to everyone, as it should be; there’s so much there that inspires. But on this one, our perspective—our history—remains unique.

***

Me? I always remember the sign.

When I pulled my rental car onto North Maple Street on that spring day in 2001, the sign was the first thing I saw. It was one of those standup, marquee letter boards you can spell things out on, and someone on the staff at St. Vincent-St. Mary High School had taken the time to post a simple message: WELCOME SLAM MAGAZINE. We were used to warm receptions from young ballplayers excited to get in their favorite magazine, but even for us, this was a first.

But LeBron himself? LeBron played it cool. That first impression lingers: Already pushing 6-7, a rangy, broad-shouldered kid with a slightly unkempt afro, his hair longer than it has been ever since. He talked fast, and he was funny, a bit of a smart ass, and about as cocky as you’d expect of a sophomore who had recently been named Mr. Basketball for the state of Ohio.

It’s semantics, perhaps, but there’s a difference between cockiness and arrogance—the former implies supreme confidence, a certainty of how good you are, while the latter diminishes those around you as somehow less. With LeBron, it was something different. Even then, on that first day, it was clear this was not a kid who separated himself from his friends and teammates. He was a leader, no doubt, but a leader who craved camaraderie, and who was most comfortable with his boys in close proximity.

Not that he didn’t occasionally have some fun with his alpha-dog status. That April day of our initial visit happened to coincide with the delivery of a few FedEx boxes addressed to the St. V athletics department. The boxes were scattered about the bleachers in the school’s small gymnasium that afternoon, when LeBron and his teammates turned out for a lightly organized pickup run. The boxes held the school’s 2001 OHSAA state championship rings, their second haul of jewelry in as many years.

After the game, an ugly fullcourt run in which LeBron looked mostly disinterested, the players made their way to the bleachers, where they noticed the FedEx boxes. One of them began digging into the cardboard container and eventually pulled out the small jewelry box he was looking for. Seeing this, LeBron barked, “Put it back.”

Defiant, his teammate barked right back. “Why are you worried about my business? This ain’t your team.”

“Yes it is my team,” LeBron replied. “Put it back.”

None of it was serious, but it nonetheless spoke to an obvious truth: This was LeBron’s team, in as much as his innate ability, even as a sophomore, was far superior to everyone else in the gym. (This on a roster that would produce a half dozen college players and a couple of overseas pros.) At 16, he was the best player in the state, and quite possibly the nation. How could it not be his team?

Given all that, it’s not hard to imagine what a headache this kid might have been to coach. The reality, of course, was just the opposite. “LeBron doesn’t have a selfish bone in his body,” Keith Dambrot said that afternoon. An Akron native and former Division I college coach, Dambrot had returned to his hometown a few years earlier and found himself running some skill sessions for local middle-school kids on Sunday nights at the local Jewish Community Center. LeBron was among them.

Basketball-wise, from those Sunday night runs through the previous two seasons at St. V, Dambrot knew LeBron as well as anyone. To hear the coach talk about him—praising his potential with a calm, almost casual certainty—was to be convinced that this kid’s future was brighter than the sun. And it started with just how coachable he already was.

“If your best player’s not a hard worker and doesn’t share the ball, it creates issues,” Dambrot said. “When your best player gets off on passing, that helps. He’ll go through games where it doesn’t matter to him how much he scores.”

It’s wild in retrospect, but of course there was no way of knowing then the narrative that would develop over the course of LeBron’s career: that of the “pass-first superstar” who allegedly lacked the killer instinct of guys like Kobe and Mike. Even Dambrot admitted that, at 16, LeBron “liked” to win, but perhaps wasn’t obsessed with winning in a way that seemed to define the game’s true elite. But the coach wasn’t worried, and certainly didn’t see it as a weakness—in fact, where LeBron was concerned, he wasn’t sure he saw any weaknesses at all.

“He does everything,” Dambrot said. “He just needs to fine-tune. Sometimes he doesn’t defend, but he can defend. Sometimes he doesn’t rebound, but he can rebound. He’s a good shooter—a little streaky, but I think if he spends a lot of time at it, he’ll be a great shooter. Most guys that dominate at this age do it athletically, but LeBron has done it with skills and knowledge. He just understands the game. In order to get better at this game, you’ve got to be able to learn. This guy is amazing from that perspective.”

It was enough to make you forget about the skill part—almost. At that point, Dambrot said, LeBron was “getting bigger, stronger and better almost every month.” All of which led, inevitably, to the question of comparisons: LeBron could be the next _______? Again, this was 2001, so it made sense that Kobe Bryant and Tracy McGrady were the names most often mentioned. But neither was quite the perfect fit. Nor was Michael Jordan, who was then the consensus GOAT and LeBron’s favorite player. But again, their games differed in too many ways.

As his coach, Dambrot had every reason to push back against any such comparisons, lest a player already overwhelmed with praise get another reason to believe the hype. Only Dambrot didn’t push back. He doubled down with a comparison of his own.

“LeBron’s a unique player,” he said. “He’s a little like Magic Johnson, in that he can really pass. Then he’s a little like Kobe, and he’s got some Tracy McGrady in him. He’s such a great player, the hype doesn’t bother me at all.”

Twelve years later, as LeBron was coming off his second NBA championship, I reminded Keith Dambrot of that conversation, and asked if anything LeBron had done since had surprised him. Dambrot was blunt: “I can honestly say that he hasn’t exceeded what I thought he could do.”

***

There are more memories from that day: dinner with LeBron and his mom at an old steakhouse around the corner from the high school, where he signed an autograph for one of the cooks. We worked out the details of a photo shoot to accompany our story, and an agreement that he’d take over our monthly high school Basketball Diary for his junior season—the first non-senior to hold down that spot. He was up for all of it—as that sign out front of the school made clear, this was all new, both to LeBron and to St. V. The attention was a thrill, and it was welcome.

Before his prep career was done, St. V would institute a strict policy barring media from campus. That’s just how crazy things got.

Long before everything around LeBron seemed to spin out of control, we established relationships and trust—not only with LeBron, but also with his family, friends, teammates, coaches and the adults whose presence in his tumultuous early years helped keep him focused and out of trouble. This magazine’s mission from Day One has been to tell the players’ stories—and, whenever possible, help the players tell their own. With LeBron more than most, loyalty mattered, and still does.

As we shadowed LeBron over the next two seasons, the people he trusted and relied on were almost always nearby. When I stood in the back of an overcrowded arena pressroom in Trenton, NJ, in the winter of 2003, listening to LeBron field questions from national reporters after a 52-point outing against a top-10 opponent—so much for lacking that killer instinct—his mother, Gloria, stood next to me. When we hooked up a visit to the old Mitchell & Ness store in downtown Philadelphia, at the height of the throwback craze, LeBron insisted on bringing his entire team along.

By the final portion of his senior year, of course, it all got absurd: showcase games on ESPN, and his sold-out home games on local cable pay-per-view; media coverage that hinted at TMZ before the celebrity gossip site even existed; suspensions by the Ohio high school governing body that, in the age of Big Baller Brand, look even more ridiculous now than they did at the time. It was a circus, fully unprecedented and, to the extent it all centered on one kid, unlikely ever to be replicated.

Looking back, there’s no doubt the madness of LeBron’s high school career prepared him for the glare of the spotlight that has shined on him ever since. He never really asked for it, and he’s had minor stumbles along the way, but mostly, he has excelled. For those of us who were there at the time, little that he’s done on the court has come as a surprise. His off-court prominence is another story. We can’t say we predicted his rise to mogul status, his relentless efforts to lift up his community, his loud, clear voice on issues of social justice. In that, our memories of that funny, cocky 16-year-old kid perhaps made it difficult to imagine the man he has become.

But in another way, the perspective we earned back then remains invaluable. He’s still that dude who’s intensely loyal to his people, the family, friends and teammates who remain among his closest connections. He still dominates on the court with that unsurpassed mix of skill, instinct and work ethic. He still amazes, and he shows no signs of letting up. LeBron is still writing his history, but for us, those early, unforgettable chapters will forever inform our view. Lucky us.

SLAM Presents LEBRON is available now! Buy it here.

—

Portrait by Clay Patrck McBride

Action shots via Getty Images