The King of Queen City: LaMelo Ball’s Ascension to the Top is Only a Matter of Time

It’s June 24, 2019. The beginning of the last “normal” summer that Americans—and the world—will experience in a long time. Nothing will be the same.

But on this night, many die-hard hoops fans are glued to their television screens and phones while the NBA celebrates the culmination of the 2018-19 season. The third annual NBA Awards, live from the Barker Hangar in Los Angeles and airing on TNT, will reveal the winners of some of the League’s most prestigious accolades. Giannis Antetokounmpo is about to earn his first of back-to-back MVPs. Luka Doncic is picking up his ROY hardware. Superstar hoopers aside, though, the night also features celebrity presenters. Samuel L. Jackson. Tiffany Haddish. Issa Rae. Shaquille O’Neal. And then there is actor and comedian Hasan Minhaj, who takes the stage to let off a few jokes. One joke in particular is about to become a trending topic on Twitter.

“In the past two months, AD got traded, Zion went first and LaMelo Ball got shipped to boarding school in Australia. I can say that joke—neither of us will ever make the NBA,” says Minhaj, as some laughs break through the crowd.

Comedians crack jokes. That’s the point. But whether Minhaj actually believed what he said, only he knows.

The irony of it all (aside from the fact that Melo went on to become the third overall pick in the draft the following year and won ROY a few months later) is that here was a 17-year-old kid who had become such a staple of hoops culture that he was the subject of a joke on a night meant to celebrate the game’s current greatest.

About 50 miles east from where the awards were taking place, it didn’t take long before LaMelo, at home in Chino Hills, reacted online. He posted a comment, which was later deleted, that essentially questioned if Minhaj would say that to his face. Normal teenager reaction. All harmless.

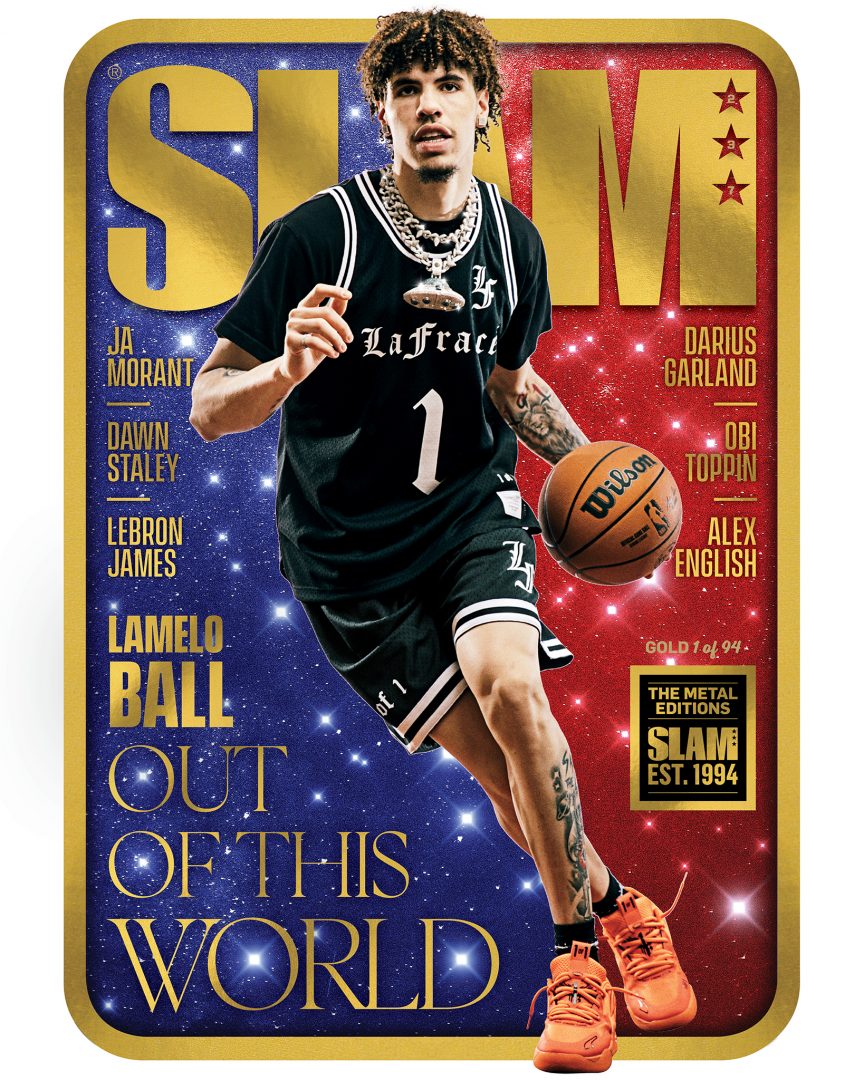

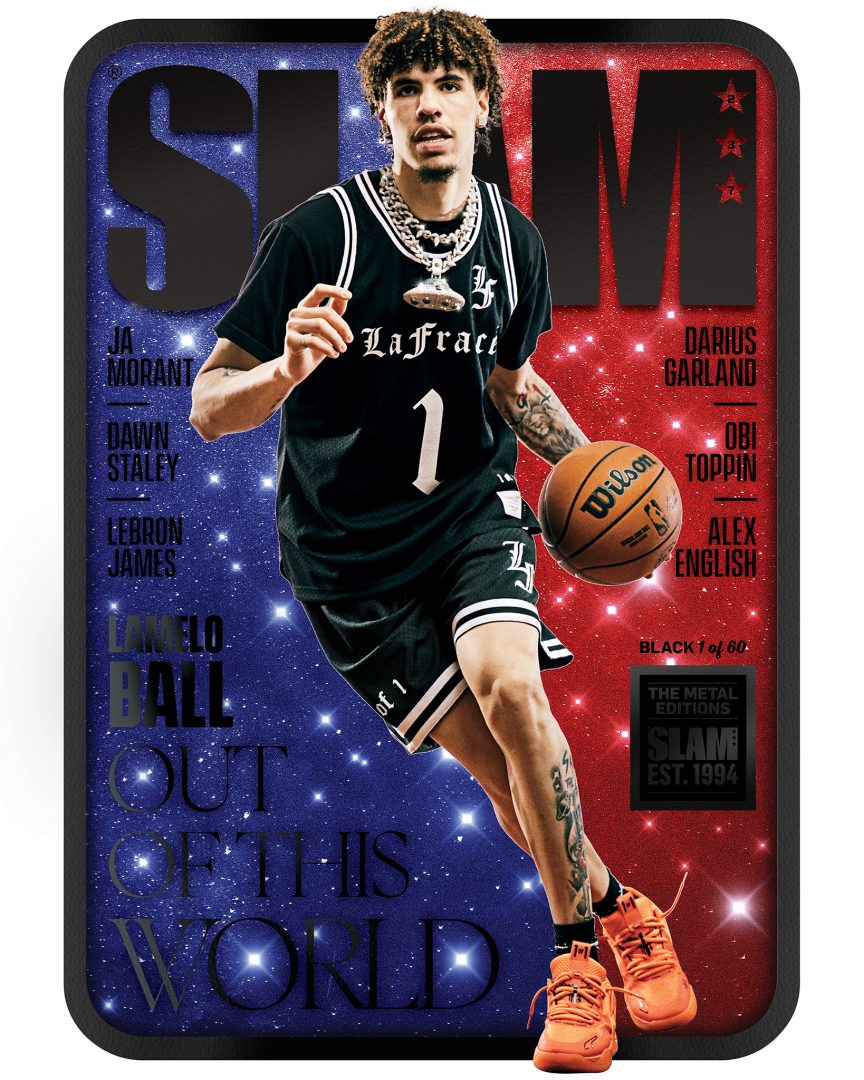

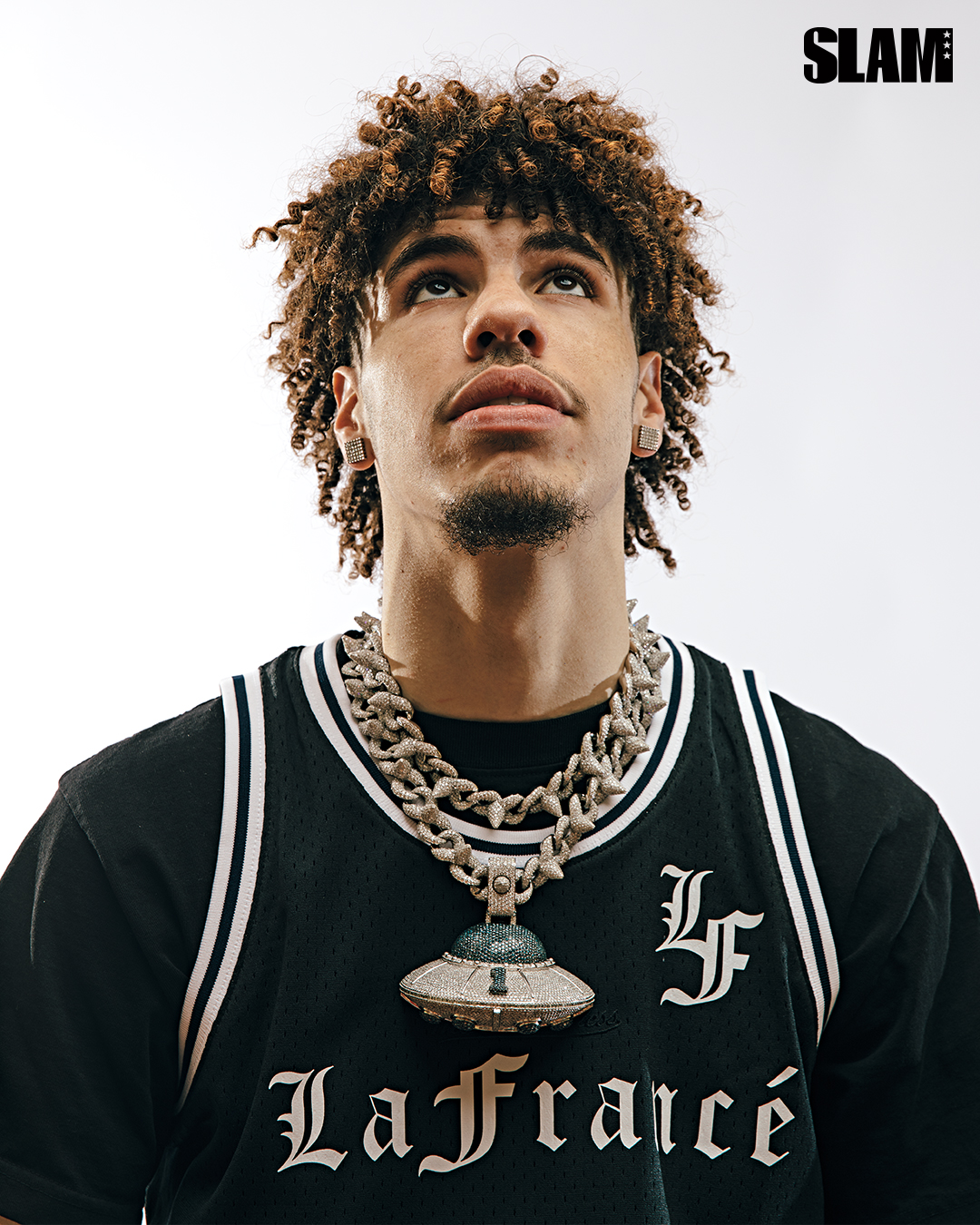

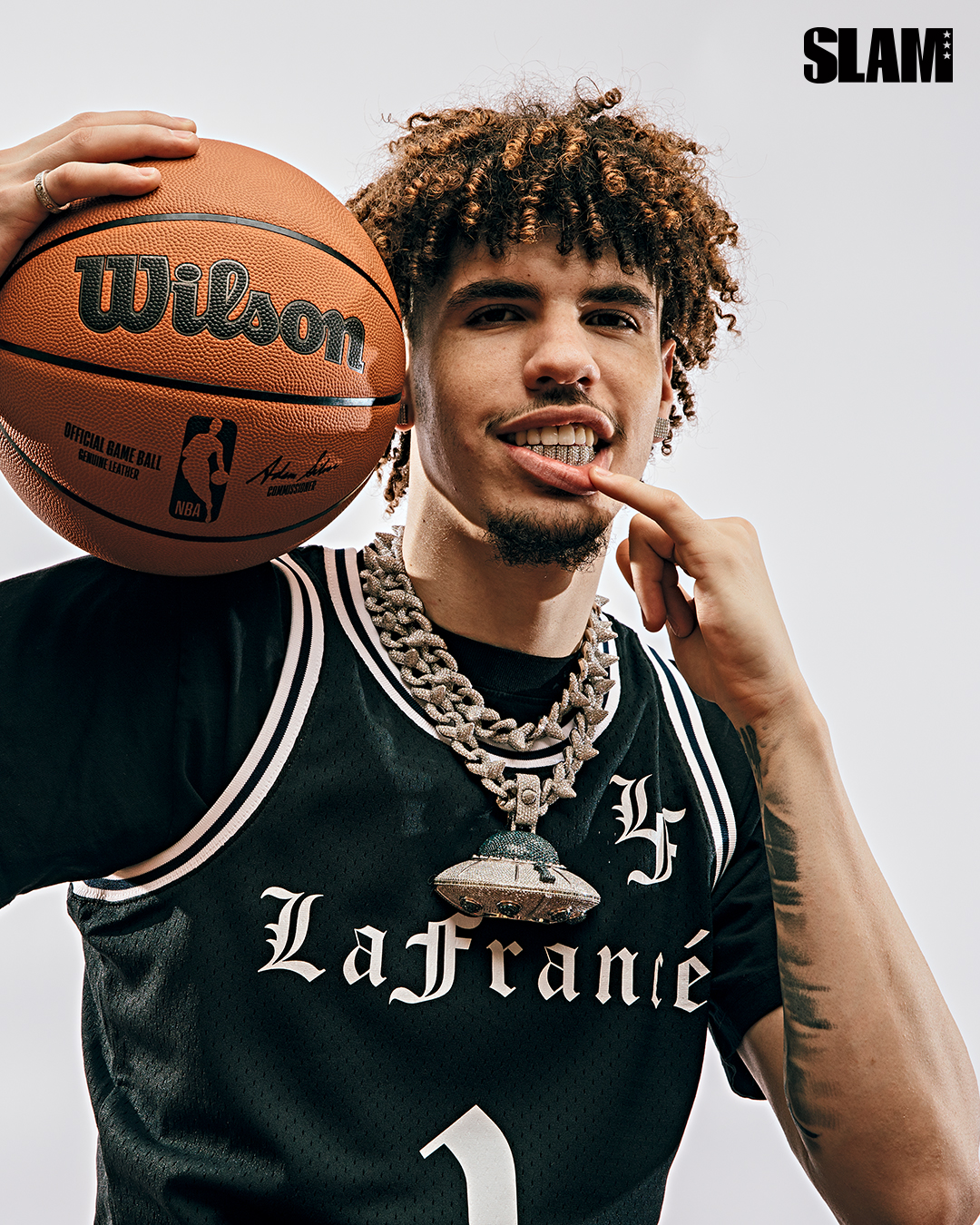

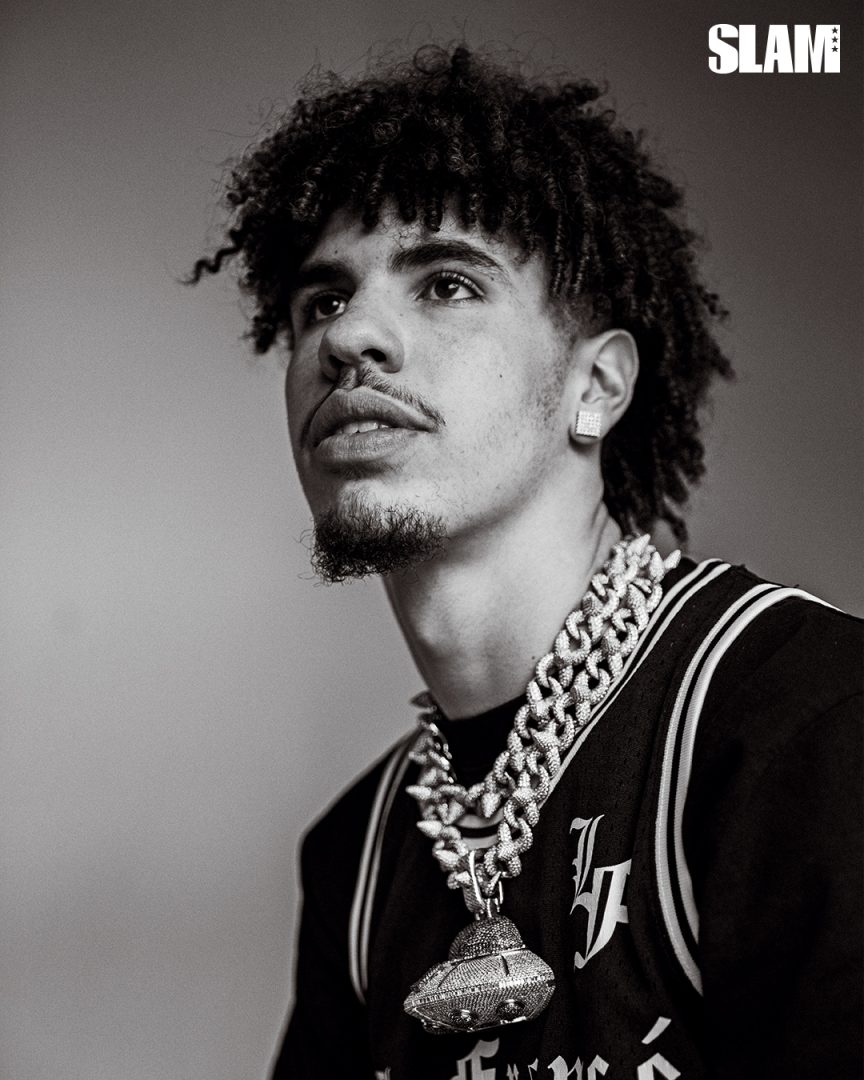

Almost three years later, LaMelo is now sitting on a table in a Charlotte hotel conference room on a late February afternoon. He’s wearing a custom 1-of-1 LaFrancé-branded basketball uniform (his personal lifestyle brand, named as a nod to his middle name) while rocking a No. 1 jersey, which he says he expects to be his new number starting next season. And then there’s the humongous iced out double chain around his neck with a 3D UFO spaceship. Casual.

We just wrapped up his cover shoot and he is comfortably lounging as he reminisces on his journey so far.

SLAM 237 featuring LaMelo Ball is available now!

He’s no longer that bubble gum teenager who many predicted was all internet hype and would eventually fade into obscurity. To be fair to Minhaj, he was probably just repeating what he had heard others say—some who even consider themselves basketball experts repeated those same sentiments back then, too. On the night of the 2019 awards ceremony, ESPN had Melo projected as a second rounder in the draft. The 32nd pick, to be exact.

As Melo is reminded of the days when many doubted him, and specifically the night of the awards, he begins cheesing hard. It’s the smile of someone who knows he’s had the last laugh. He always knew he would. And he enjoys every bit of it these days. But as I remind him of his deleted comment from that night, he can no longer control his laughter.

“Oh, I said that?! That was probably me on some young shit. I’ll smack that n—a, for real!” he says before breaking out into more laughs.

“Nah, I don’t really give a fuck when people said stuff like that. It’s all jokes to me, for real. When you say something, I’m gonna say something back. You mean it? Eh, I don’t mean it. Could mean it. Probably don’t. Probably do. It’s whatever.”

Melo ain’t really sweating it. He never has. His nonchalant demeanor has lowkey played a big role in getting him here. If anything, it’s probably what kept him sane when his notoriety was exploding in high school, and yet media outlets and online trolls alike refused to acknowledge him as a legitimate high-level NBA prospect. Talent is obviously needed to get here. But ask all of the cautionary tales and highly touted high school players who never panned out about their voyage, and the importance of mental strength will be a common theme. Goes without saying that being under a microscope and the type of spotlight that Melo grew up in is not for the faint of heart.

Melo, though, shrugs and scoffs at the thought (technically, the question) that there was ever even the smallest of chances that all that noise was ever hard on him. That lowlight mixtape that accumulated millions of views online when he was only 15 years old? He’s practically offended at the thought that he would ever be offended by it.

“I ain’t gonna lie, everything was just normal to me. I give a lot of credit to my pops, just the way he had us. Pretty much saying, If they not talking about y’all and they not hating on you, you’re pretty much not doing nothing. You feel me? If they not hating on you, you obviously not doing something. If they talking about you good, if they talking about you bad, they’re still talking about you,” says Melo. “I never really looked at it like, Oh, why are they talking about me like that? If you not really in my household, I don’t really care what you got to say. No disrespect, but it’s like that.”

Continuing to look back on his father’s words: “He said, Y’all destined for the League, type-shit. Made us really believe it. I came out the womb believing it. When you got that factor and really believe it, that’s really it. All you could do is make it, for real. That’s what our mindset was…I felt like I could play in the League when I was 14, 15. I probably couldn’t have, but that’s just how I thought. I was like, It’s just basketball. He could shoot, I could shoot. He dribbles, I dribble. From the beginning, I thought I was always—no one could really f**k with me. I just always had that attitude.”

In late 2017, when Melo left Chino Hills High School at the beginning of his junior year and turned pro in Lithuania, he says that’s when he received his big affirmation—or rather, revelation—that there was nothing that could stop him. At the time, people criticized the move, saying it would hinder his growth and development, and ultimately obliterate any probabilities of him making the NBA.

“Honestly, after Lithuania, I didn’t give a fuck where I got drafted to. The beds? You roll off to the left, you fall off. You roll off to the right, you fall off. Motherfucking calves hanging off the bed—not feet, calves hanging off the bed! It was bad, bro. Once you get through that, it was like, I don’t care where y’all put me in. As long as I’m in the States and I got water, I’m good,” Melo says confidently. “That whole shit, bruh—it felt like one big ass night! That shit was crazy. Food was hard to eat out there. Hella cold. Nobody around. That’s pretty much when I just locked in. I’m like, Yeah, I don’t really need too much. Just get it done and grind. That right there was big, I feel like. Sacrifice—you feel me? That’s what I looked at it as.

“The mental shit goes back to Lithuania. Ever since all that, I aint gon’ lie, my mental has been straight. It ain’t nothing you can do. I even sat the bench there. I literally did everything out there.”

LaVar still remembers Melo getting in trouble in preschool as if it was yesterday. One day, the teacher had asked the class what their favorite song was. Every kid took turns as the teacher went around the room. When it was finally Melo’s turn to speak, he excitedly shared with the class his favorite lyrics.

“This dude starts reciting a DMX song with all the cuss words in it! His teachers said, Hold up, wait a minute! He had never been [in a situation] where someone would say, Hey, don’t say those cuss words! ’Cause I let him listen to rap when getting ready for the games. So he was always listening to DMX and what his older brothers were listening to,” recalls LaVar. In 2016, Zo did say that his five favorite rappers of all time were Lil Wayne, Future, DMX, 50 Cent and Tupac, so it’s easy to see where that came from.

LaVar shares the childhood story to get to a bigger point. Being the youngest, Melo would always hang around his older brothers. Wherever Zo and Gelo went, Melo was there. That included the basketball court. Melo felt he could hang with them on the court, but then also invited himself to hang off the court, too. It got to the point where Melo was practically hanging with Zo’s and Gelo’s friends more than kids in his own grade. It was really just an extension of what was happening on the hardwood. LaVar had his boys playing up in age in AAU. Do some Googles and you’ll find videos of an 11-year-old Melo playing against high school kids next to his brothers at AAU events. Not just playing against high school kids at 11, giving them buckets.

“We used to have movie night every weekend. I used to say, Each of you guys invite a couple of your friends. And Melo never invited his. He always invited Lonzo’s and Gelo’s. The older guys. Melo never wanted to hang out with no little guys,” LaVar says. “By the time we were playing in the high school leagues, and the boys were super young, I always had a couple of guys on the team that were 17 to balance that stuff out—needed some big boys to rebound. These dudes had tattoos and goatees and my dudes were barely in elementary. But they looked at [Melo, Gelo and Zo] as little brothers and protected them. [Melo] always talked crazy. He talked like them. You’d hear a little kid’s voice talking, and then you hear him talking about stuff that grown folks talking about. He was always like that.”

But on-court development was only part of the plan. There was a whole other social aspect to it. LaVar decided to raise the family in the relatively affluent Chino Hills enclave, far away from the South Central L.A. streets he grew up in. He and his wife Tina would end up taking the boys back to W. Slauson and S. Van Ness all the time, though. After all, their grandparents still lived in the neighborhood. And aside from visiting family, he also wanted the boys to build up that same inner-city grit and toughness he had mastered. He wanted the boys to appreciate the unique situation they were in back in Chino Hills, and to also be cognizant and understanding of the different social conditions others less fortunate were born into. The routine trips to South Central ultimately became a major part of the boys’ development.

Still, part of that preparation was also about making sure that Melo and his brothers wouldn’t get caught up in the glitz and glamour when they finally made it to the League. That the transition would be as seamless as possible because their lifestyle would be no different when that day came. Growing up around gated communities in Chino Hills was one thing. But Zo pulling up to high school in a new white BMW 7 Series and Gelo pulling up in a separate one—yes, to the same school parking lot—was just as much about preparing for the League as any drill was. When Melo finally turned 16, he famously got a Lamborghini gifted to him. Not many outside of the family understood the purpose of it all at the time.

“If I wanted my sons to live the NBA lifestyle, you can’t dangle no fucking shoe in front of them, like you can do with the other superstars. You offered them some shoes, they were gonna be like, What am I supposed to do with these shoes when I got a BMW outside? You get to the League and now you can finally buy that BMW or Escalade you always wanted. [Melo, Gelo, and Zo] already had that in high school,” says LaVar. “Just like with Melo, when the media asked him if he was happy to have his own signature shoe [with Puma], he told them he’s had that since he was 16. He’s not gonna feel any different if we made sure that he felt those experiences at 16. Guys are out there breaking their neck trying to get a signature shoe. He’s been through all of that. You can’t re-do it. You can only have that feeling one time.”

Adds Melo: “Right when I hit that age, everything started making sense. I had been through everything. Even with the whole playing on teams—I really started to see what my pops was doing. Even when we were younger, we always used to play on our own team under him, with just local kids. We wouldn’t go find the best teams. Then you look back at it and it’s like, Damn, that’s ’cause he wanted me to pass, shoot, rebound, steal. Damn near do everything. So, when you do get on those types of teams and you got that [NBA] talent around you [now], it’s way easier.”

So here we are today. Melo is now the face of an NBA franchise at only 20 years old. A franchise and a city that didn’t have much to cheer about prior to his arrival in 2020. The impact is evident in the significant increase of new season ticket holders that the team has reported since he touched down in the Queen City. In the fact that they’ve been in contention for a playoff spot the last two seasons after finishing almost 20 games under .500 right before he got to town.

Some of his early accolades make his trajectory scary—in the best way. He’s already joined some elite company in his short time in the League. Fourth-youngest ever to be an NBA All-Star, behind only Kobe Bryant, LeBron James and Magic Johnson. He finished with 18 points off the bench that night. There was a period earlier this season when he was the team’s leader in points, rebounds, assists and steals per game (Mason Plumlee has since taken over the rebounds category). The only other player in the League who was leading his team across all four categories at the same time this season was reigning MVP Nikola Jokic. Melo became the second youngest player in NBA history to reach 700 career assists in February, behind only LeBron. There’s a bunch of other similar milestones, where his name sits next to some of the best.

But it hasn’t all been peaches and cream. As we headed to press, the team had dropped 13 of its last 17 games. The Hornets are fighting tooth and nail to hold on to one of the last remaining play-in game spots. And while Melo is focused on securing a postseason opportunity, he’s also aware that it’s all just a process. Just like his road to the NBA. From Lithuania to LaVar’s JBA world tour (which took him across Europe) to Australia, he’s become confident in knowing that not much in his life has been a matter of if, only when.

“When they really put them keys in my hand, I feel like it’s gonna be a whole new situation. But until then, I’m gonna keep doing what I need to do, just try to get these wins,” says Melo. “I ain’t gonna lie, every game I feel like I can do more than what I’m doing. It’s just [about] reading the whole game and reading the whole situation. And everybody being on the same page. The consistency part. Once all that clears, I feel like we’ll be straight.

“The season isn’t successful until you win a championship. But it’s [also] pretty much always about being better than the last year. So, last year we were in the play-in. This year hopefully we get in the playoffs, win a first round, something like that. Just keep going up from there. I just feel we’re like a big away. One that can clog up the whole paint, rebound. Put that bitch in my hands [and] let me rock! That’s how I be feeling. And then we’re gonna be straight.”

Portraits Diwang Valdez.