From high school, to college, to the NBA, people were always harping on what Mark Jackson’s physical limitations prevented him from doing. Well, enlightened fans (um, such as yours truly) liked to focus on what Mark could do: pass the ball like a savant, and with flavor to boot. Just check the stats (and the sponsor of that page)! The article below, from SLAM 25, was both my first SLAM feature and the first (and only) SLAM feature Mark’s gotten. Yes, I’ll holler at him for an Old-School joint soon.

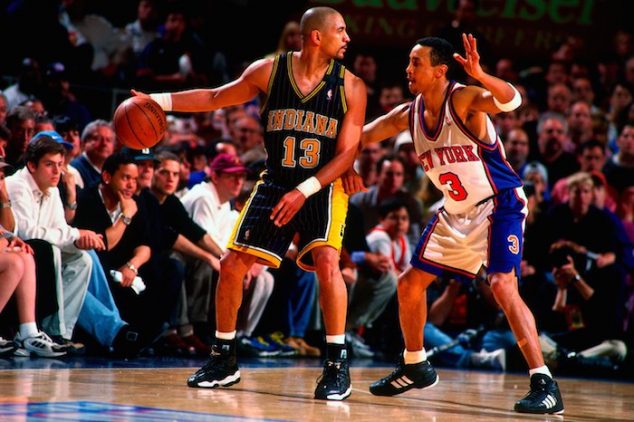

As soon as he catches the in-bounds pass, the slow and steady attack begins. He pounds the ball in an unsightly high dribble as he approaches mid-court. When a defender approaches, the high dribble gets nastier, because now his back is to the basket. There’s not much quickness and even less true speed. He stands a real-world 6-3, his 32-year-old body no harder than your average high-school baller’s. At the local playground you probably wouldn’t look twice at this guy. And on an NBA court? Hell, you wouldn’t even look once. But then…

Somehow, while facing the wrong way, Indiana Pacers’ point guard Mark Jackson sees Reggie Miller cutting along the baseline and hits him with a perfectly-placed pass. “Wow,” the non-believing fans says, “How’d he do that?”

It will continue throughout the game. There will be more blind passes. There will be perfectly-timed lobs that lead gangly center Rik Smits to the hoop, and crisp bounce passes that get Chris Mullin wide open looks. Turnovers are a fantasy of the opposing coach, because Mark doesn’t provide them. His teammates stay in the game, because they know they’ll get the ball.

“Everyone wants to play with Mark Jackson,” Mullin says in his vintage Brooklynese. “You go around the league, and people are like, ‘Man, I wanna’ play with Mark. Lemme get with Mark. I like that guy.’”

Besides flawless leadership and the usual 10 assists, by the end of the game Action Jackson will have dropped in a few eye-opening baskets and done a crowd-pleasing dance or two. And maybe he’ll have recruited a new set of believers.

Jackson is a throwback’s throwback. In an era of versatile, “do-everything” players who dabble in all facets of the game, Mark is a specialist. He’s a passer, and he does it as well as anyone ever. Don’t believe it? Before this season ends, the all-time assist leader board will read: John Stockton, Magic Johnson, Oscar Robertson, Isiah Thomas, Mark Jackson. That’s right, fifth in NBA history, ahead of such acknowledged stars as Mo Cheeks, Bob Cousy and Nate Archibald. And Pistol Pete. And Jerry West. And Clyde Frazier. And Yinka Dare. The other-other MJ has finished in the top 10 in assists seven times, and last season—his 10th in the league—Jackson became the first person not named Stockton to lead the league in assists since Magic in ’86-87. With Mark, greatness is visible on court and in the record book, but his physical attributes (or lack thereof) have always caused people to pre-judge him.

Think about it like this: Mark Jackson, assist man for the ages, who showed his game is still extra-nice when he outplayed Iverson and Steph in back-to-back mid-season wins over the Sixers and the Timberwolves, was only the fourth-rated point guard in New York City as a senior in high school.

“I am the classic case of the turtle,” Jackson says, “the turtle that beat the hare.” Um, that would be the tortoise, Mark, but never mind. After a recent Pacers’ practice, the even-mannered Jackson uses this ancient fable to define his career. It’s an apt description.

The Bishop Loughlin HS (Brooklyn) product was considered the consolation prize in a group of young point men that included future NBAers in Dwayne “Pearl” Washington and Kenny Smith, as well as Kenny Hutchinson, who went on to the University of Arkansas. “Here were four of the best senior guards in the country, and we battled year round,” Jackson says. “It was a great time, but what I can remember is being the guy that, pretty much, people didn’t give credit to.”

He was the epitome of the cerebral, passing point guard, and—even in the ’80s—that didn’t sell newspapers or get recruiters’ attention. “I wasn’t as athletically gifted or as spectacular as those guys, so I just took pride in being solid and being a quarterback,” Jackson says. “I think that at that time, no question, and throughout my career, that hasn’t been appreciated as much.”

Setting the precedent for what has been a career filled with clutch play in big games, Jackson led his undersized Loughlin squad (Mark, the point guard, was the team’s tallest player) all the way to a state title. Jackson’s high school coach, Pat Quigley, still has good things to say about Queens’ finest. “[Mark] was so easy to coach,” Quigley remembers. “He worked the hardest and stayed the longest, so he made it easy to coach everybody else, too.”

But even Quigley doubted Mark’s on-court prospects at first. “I didn’t think he was a sure shot for the NBA. But I do remember, when he was a senior, realizing he could be a pro, mostly because of his leadership and his intelligence—he was the smartest player I’d ever seen,” he says. “I did notice his lack of quickness, but I think that’s overrated.”

It was in high school that Jackson developed the parts of his game that even casual fans recognize. First, the “teardrop”. Not quite as visually pleasing as a Michael Jordan reverse lay-up, these are the shots that Mark gets off over Mike. He methodically gets into the paint, puts his left shoulder down like a running back, gets some minor air and uses his right hand to throw the ball up, over the defender and at the basket, often going glass. More often than not, the teardrop goes in. “I picked that up from day one,” Jackson says. “It’s out of necessity to get my shot off.”

Another part of Mark’s game that goes back to Loughlin is his radical approach at the free throw line. Quigley told him to “envision the ball going through the hoop on free throws,” and Jax took the idea one step further. He started lining up his free throws by sighting over his fingers, a move that has been imitated on playgrounds from NYC to Ames, IA, ever since. The Ames fact comes courtesy of Pacers’ sharpshooter Fred “the Mayor” Hoiberg, who interrupted Jackson to point out that, in deference, he lined up his free throws in the eighth grade. “No wonder you’re such a good shooter,” Jackson replied facetiously.

High school was also when people first saw Jackson’s ingenious passing, made possible by radar-like court vision that serves him as well against the Lakers and Bulls as it did against Archbishop Molloy High.

“It’s a gift,” Jackson says. “As soon as I get the ball I take a picture of where the guys are on the floor, and I pretty much play it in slow motion as I come up the floor, and expect them to be in a certain position when the frame ends. If they’re not there, it’s their fault.” He laughs. “But that was just a gift that was given me—seeing, distributing, making plays. I can’t take any credit for it, besides putting the time in and sharpening the gift.”

With most of the nation’s bigger schools treating Jackson’s “gift” like a polyester sweater at Christmas-time, Jackson stayed local after high school, taking his street-wise game just 10 minutes down the street, to St. John’s University. Jax had a remarkable four years in Jamaica, Queens, including a sophomore year trip to the Final Four when Mullin was the star.

Jackson set an NCAA record for assists in a single season (since broken) when he had 328 as a junior, and then earned second-team All-American honors after a senior year which included per game averages of 19 points, six assists and six rebounds, plus the Big East Defensive Player of the Year award. Not surprisingly, he left St. John’s as one of legendary coach Lou Carnesecca’s favorite pupils.

“People said, ‘He can’t do this and he can’t do that,’ but he kept doing it. It’s nice to see,” Carnesecca says. “He just has this mind for the game, and he’s got eyes all over his head. You can’t coach that.”

It was under Carnesecca, a liberal and trusting coach whom Jackson loves to this day, that overt flair became part of Mark’s game. A typical St. John’s possession would include Mark dribbling the ball through his legs endlessly before taking it to the rack and leaving an over-the-shoulder pass for Willie Glass. Then he’d celebrate, wagging his finger aggressively. The post-play partying has evolved in the pros, from the finger wag to the “airplane”, when he’d run down court after a nice play with his arms spread wide, to the “shimmy”, a hip-shaking dance step that follows up a nice play these days. Poor sportsmanship?

Puhleeze, says Mark. “What I try to do is show the passion and the love that I have for the game,” Jackson says. “It’s never taunting or disrespectful, it’s just out of excitement for me and my teammates.”

Jackson graduated from St.John’s in ’87. “By graduating on time, I showed my parents I was more than just an All-American point guard—that I got the job done in the classroom too.”

He’d also earned enough respect to be considered a probable first round pick in the ’87 draft. But once again his former New York rivals were more wanted. Pearl Washington, who had turned pro after his junior year, was the 13th pick in ’86, and Kenny Smith went sixth in ’87. Jackson—the turtle—went 18th. Tempering any sadness over going so low was the fact that Jackson was picked by his hometown team.

“I dreamt one day to play for the New York Knicks,” he says. “To be out on the Madison Square Garden floor, running the point guard spot, and it happened.”

Playing at a level that matched his excitement, Jackson burst on the NBA scene as a rookie, playing more minutes than anyone in the NBA besides Mike, and running Rick Pitino’s madcap offense to perfection. He broke Oscar Robertson’s 27-year-old rookie assist record by racing up 868, almost 200 more than the Big O. To top off his storybook season, Jackson was named Rookie of the Year, the second-lowest draft pick ever to win the award. He also found a huge fan in Pitino.

“I had no problem turning the ball over to Mark, since he was a true point guard from the moment he came to us,” Pitino says. “He had talent, but he was successful because he played with such a high level of intelligence.”

With Pitino on board, the Mark Jackson story was ready to develop into a full-length fantasy. “Local boy makes good in rookie year—eventually leads team to title.” But this was no fantasy. More powerful than Pitino in the Knicks organization was absurd general manager Al Bianchi, who drafted Rod Strickland in the first round following Jackson’s rookie year. Rod’s nice, no doubt, but could you imagine the Raptors drafting a point g the year after Damon Stoudamire won Rookie of the Year? Amazingly, Mark handled the slight well, and his second season turned out to be the best he’s ever had—17 points, nine assists and five rebounds per—and a trip to the All Star game. But people kept messing with him.

Disgusted with Bianchi for a number of reasons, Pitino left for Kentucky, and Stu Jackson took over. Stu lasted a year-plus before John MacLeod was brought in. Mark went from the most progressive-thinking coach ever to two by-the-bookers. And they barely played him. During Mark’s third and fourth seasons, right on the heels of an All-Star berth and at a time when he was only 25 years old, he began racking up DNP-CDs the way he racks up double-digit assist games these days. People who knew Mark’s game were incredulous, but he kept his head and even looks back with pride.

“To show people that I can smile and high-five when I was Rookie of the Year or an All-Star, and then to show ’em, when the trials and tribulations come, that I’m still smiling and clapping for my teammates when I’m not playing the minutes I’m supposed to play—I thank God for those times,” Jackson says.

After the John MacLeod disaster, which ended in the ’91 playoffs with Mark playing only 36 minutes and scoring a total of two points in an embarrassing three-game sweep by the Bulls, the Knicks brought in Pat Riley. Playing again for a coach who knew what he was doing, Jackson averaged 8.6 dimes per game and used his floor skills to help the Knicks gut their way to a seventh game against Chicago in the Eastern Conference Semifinals. Sadly for Knick fans, Garden management had a masochistic fascination with Clipper forward Charles Smith, so Jackson was part of a package that got exiled to the NBA netherworld that is the L.A. Sports Arena. “It was tough,” Jackson says. “But I will always appreciate that Coach Riley was fair to me.”

Placed with another established coach in the Clippers’ Larry Brown, Jackson responded with a season most guards can only dream about. He played every game and dropped 14 points, nine assists, five rebounds and two steals a night. They were ill numbers, but it’s tough to get respect with the Clips. Brown left after that season, and L.A. brought in sidleine mannequin Bob Weiss.

After one season with Weiss, Jackson no longer fit in the Clippers’ plans (whatever those might have been), and he was passed on like a chain letter. He spent two full seasons with the Pacers, was shipped to the Nuggets before the start of last season, and was then returned to the Pacers in February.

“Getting moved around is part of the business,” Jackson says. “As for last year, well, that’s something I’ll think about years from now, telling my kids and grandkids how I beat out the great John Stockton to lead the league in assists.” A nice thought—the passer, passing on his story.

Despite the trades, Jackson stays with his family. “We have a permanent home in New Jersey, but I’m a family guy, and where I play is where my family is at that time,” he says, thrilled to discuss his wife Desiree, his six-year-old son Mark II and his three-year-old daughter Heavyn. “It’s important for me to come home and spend time with them…I’m not a guy that’s trying to run the streets and live a hidden life.” Jackson ties his wedding ring into his shoelaces during games to show how proud he is of his marriage.

Placing your family, God and your team before yourself doesn’t jibe all that well with the selfishness and coach-beating that currently reigns in the NBA, which makes Jackson a refreshing sight to others. “He’s a great guy with a great family,” Carnesecca says. “To this day, I just love to be in his presence.”

Other players also have lots of love. “I get a vibe off certain people, and Mark’s one of them,” says Trail Blazers’ point g and fellow Queens native Kenny Anderson. “I always looked up to him for how he handled the media and how he played.”

This season, Jackson’s up to his usual tricks. As of press time, he’s fourth in the league in assists and first in the league in assist to turnover ratio, and he’s convinced another coach that he’s got game. After a 2-5 start to the season that saw Jackson play about 18 minutes a night, Larry Bird started letting him play, and Indy’s playing the best ball it has all year. “We wouldn’t be where we are without him,” Larry Legend recently told the Indianapolis Star-News.

Jackson’s passing has carried off the court as well. Passing on knowledge, that is, to the Pacers young back-up point, Travis Best. At practice, Best has been all over Jackson, laughing, talking and listening.

“We compete every day in practice and try to make one another better,” Jackson says. “He wants to improve, and he’s been listening to what I have to offer him.”

Passing the ball, passing the knowledge, passing the praise—this is what he does. As Mark “Action” Jackson begins considering what he’ll do when his record-book altering career (remember, fifth all-time in assists) comes to a close, the choices are simple. “When it’s all over, I’m just gonna sit down and say, ‘God, what do you want me to do?’ Whether it’s coaching, where I can use my knowledge of the game, or preaching the word of God, I’ll give it my all and try to have an impact on people’s lives.”

Funny. We thought that’s what he’s been doing all along.

Ben Osborne is the Editor-in-Chief of SLAM Magazine. Follow him on Twitter @bosborne17. Images via Getty.