In the middle of January of 1999, Madison Square Garden President Dave Checketts, New York Knicks General Manager Ernie Grunfeld, Knicks Assistant GM Ed Tapscott and Knicks Head Coach Jeff Van Gundy traveled to Milwaukee to meet with Latrell Sprewell, who was in the middle of serving out a 68-game suspension from the NBA after choking his previous coach, the Warriors’ PJ Carlesimo. It was one of the biggest meetings of Sprewell’s life—the result of which could lead to the Knicks trading for the then-29-year-old, giving him a second chance and changing the course of his career—and Van Gundy expected the Wisconsin native to be dressed to the nines, ready to court his newest suitors.

Sprewell wore red basketball shorts and a wife beater.

“I was immediately impressed by that, in an odd way,” Van Gundy says now. “I immediately knew that this guy is who he is. He was never trying to impress somebody else by what he did or what he said—he was being himself.”

If nothing else, Latrell Sprewell was always himself. This cost him relationships with both teammates and coaches and damaged his reputation more than a little bit, but he never seemed to mind—he was unapologetically himself both in and out of the spotlight, though he’s made it abundantly clear he’s always preferred the latter.

We wanted to speak with Latrell about his playing career and his post-NBA life. He had no interest in doing so, which shouldn’t come as much of a surprise; Latrell never much enjoyed interacting with reporters of any sort. Which is unfortunate, because, from what we do know of the time leading up to his disappearance from the public eye, it really was quite the journey.

Sprewell was born in Milwaukee, spent a chunk of his childhood in Flint, MI, then returned to Milwaukee after his father was arrested for possession with intent to distribute in Michigan. During his junior year at Washington High School on the north side of Milwaukee, basketball coach James Gordon spotted a gangly Latrell—all 6-4, 170 pounds of him—walking down the hallway and asked if he’d have any interest in playing basketball. Sprewell had been cut from the team as a freshman back in Flint, but, under the guidance of Gordon, he decided to give it a go once again.

He was good. Like, really good: Long, athletic, a lock-down defender with a solid mid-range shot and in-your-face intensity to boot. Gordon, through a friend named John Hammond (then an assistant at Southwest Missouri State, now the General Manager of the Milwaukee Bucks), set Sprewell up with Gene Bess, head coach at Three Rivers Community College, a local junior college. Spree grew to 6-5, filled out a little, and played with a mean streak that had him shutting down wings on one end and driving past them on the other. “The thing that impressed me most with him was that he was so coachable,” Bess says. “You didn’t have to tell him every mistake he made—he learned from other players. You only had to tell him [instructions] once.”

He did a couple years at Three Rivers, then a couple years at the University of Alabama, where he live inside the basketball team’s arena one summer as he worked meticulously on his game with one of the program’s managers every day. “Spree could run,” says Wimp Sanderson, his coach at Alabama. “He got a lot of cheap baskets, and he could take the ball to the basket. The more he played, the better he got.”

Sprewell was drafted 24th overall by the Golden State Warriors in 1992. The Warriors had just traded away Mitch Richmond, ending the fast-paced Run-TMC era, though Chris Mullin and Tim Hardaway Sr remained with the organization. They finished a rough 34-48 during Spree’s rookie campaign, but got better in ’93-94, winning 50 games with a roster that housed the likes of Chris Webber, Billy Owens and Chris Gatling. Sprewell, per reports at the time, felt that they had a solid foundation of individuals to move forward with.

Management didn’t agree. In 1994 they flipped Webber and Owens—leading Sprewell and Gatling to write their traded friends’ numbers on the back of their sneakers—and Nelson left in early 1995 with Golden State’s locker room still furious with him for his unnecessarily contentious relationship with Webber, who was the ’93-94 Rookie of the Year and pretty obviously a future many-time All-Star.

“At that particular time, the whole organization was going different ways,” Hardaway Sr says. “New ownership. New management. New GM. Don Nelson was out, and now you had Rick Adelman coming in. [Adelman’s style] suited us, but we had to change everything around.”

Adelman and Hardaway didn’t get along—the perpetual theme with the 90s Warriors is just about every group following the Run-TMC era had some sort of player-coach or player-player infighting—but Adelman and Sprewell bonded just fine, and despite the team’s mediocrity, Latrell played well, establishing himself as an elite NBA guard. He made All-Star games in ’94, ’95 and ’97 and the All-NBA First Team and All-Defensive Second Team in ’94. The high-energy Sprewell was named Team Captain in 1996, then was gifted a four-year, $32 million contract that summer. In ’96-97 he averaged 24.2 points (his career-high), good for fifth in the NBA.

But despite the on-court success, the off-court confrontations were…aplenty. In 1993 Spree fought with teammate Byron Houston, who clocked in at 250 pounds and looked more defensive lineman than small forward. In ‘95 Spree went at it with Jerome Kersey at a practice; he then left the practice, only to return minutes later holding a two-by-four.

And then there was the incident. The Warriors replaced Rick Adelman with PJ Carlesimo in 1997. Then the ’97-98 Warriors began the season 1-13. Then on December 1, 1997, a frustrated Latrell Sprewell snapped on Carlesimo during a practice. Carlesimo reportedly told Spree to “put a little mustard” on a pass, leading Spree to tell Carlesimo to back off, leading Carlesimo to do the exact opposite, leading to Spree’s hands winding up around Carlesimo’s neck.

(The strangest part of the incident, which was detailed in a report by an independent arbitrator named John Feerick and later relayed by New York Magazine, came courtesy of Warriors role player Bimbo Coles, who was on the court putting up jumpers while this all went down across the gym. Coles turned around at exactly the moment Spree had Carlesimo’s neck in his grip, but was so baffled by what he was seeing, his brain simply didn’t register it—so he turned around and took another shot. Shout out to Bimbo Coles.)

Sprewell would soon get slapped with a one-year suspension, becoming arguably the most vilified NBA player of his era in the process. He was the late 90s Ron Artest—post-Malice, pre-Metta.

“I never saw him ever lose his temper in practice or in a game,” Bess says. “I had to do some correcting, just he and I, and I was always impressed that he didn’t ever try to retaliate in any way, shape or form. [The incident] was a shock, honestly.”

After the penalty was handed down—following arbitration, the punishment became a 68-game, rest-of-the-season suspension—Sprewell did what anyone else in his shoes would do: He went home. In Milwaukee, he trained his cousin, Ceso Sprewell, a then-16-year-old student at Washington High School. And he waited. Eventually the NBA, stuck in a lockout, granted two teams permission to speak with Spree: New York and Miami.

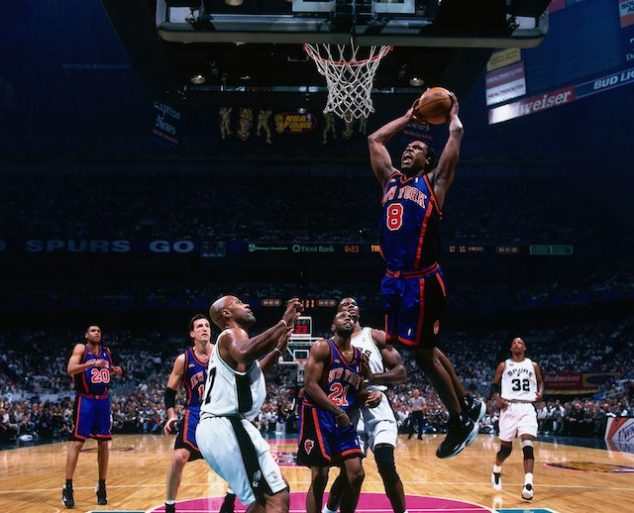

The Knicks brass’ trip to Milwaukee was a success, as was so much of what followed it. Sprewell helped the franchise leave behind its mid-90s core of John Starks and Charles Oakley (Patrick Ewing remained, though), and, along with Ewing, Allan Houston and Larry Johnson, he brought the 8-seeded Knicks to the 1999 Finals. “Latrell, because of his competitiveness, intelligence and athletic ability, really gave us a boost defensively,” Van Gundy says. “Offensively, he and Houston, after they grew together and learned how to play together, they really complemented each other extremely well.”

They lost those Finals to the San Antonio Spurs, but no matter—Sprewell 2.0 had arrived. He proudly stated, “I’m the American dream,” in an AND 1 commercial. He was featured on the cover of this magazine. The following season he slid into the starting lineup as the Knicks’ premier small forward, averaging 18.6 ppg and 4.3 rpg in ’99-00. He became an All-Star in ’00-01. And he was so, so fun to watch; his fierce two-handed slams would remind the modern NBA fan of a certain Oklahoma City guard.

“He came to New York and the Knicks at the right time for himself, and the right time for the Knicks, and the city embraced him,” JVG says. “That run from when he came, those first couple of years—tremendous. When he was running the left wing and we advanced it to him, and he was running full speed and his brakes were flying and he was attacking, it was a sight to behold. The athleticism, the flare, the tenacity—it was a beautiful thing.”

Sprewell also became a cultural force. He started a rims company that helped popularize spinning rims, which were the car-accessory of the moment for the better half of the early 00s. Then after helping AND 1 sell a heap of sneakers, he linked with DaDa, who introduced a sneaker with a spinning rim inside of it. Outside of the great Allen Iverson, you can’t find a basketball player of the late 90s/early 2000s with an equal amount of credibility in the hip-hop community as Spree had. Not a one.

Things in New York were really great—until they weren’t. He arrived at training camp in 2002 with a broken hand, which the New York Post reported was from a fight he had on his yacht. (Sprewell denied that.) His scoring dipped slightly that season to 16.4 ppg, and the team finished 37-45, missing the Playoffs. Sprewell was traded to Minnesota that following summer for Keith Van Horn in a four-team deal.

The 2003-04 Timberwolves were guided by a three-headed beast comprised of Spree, Kevin Garnett and Sam Cassell. By all accounts, that should’ve been their year. They finished 58-24, first in a tough Western Conference. But the Lakers still had Shaq and Kobe, who knocked out the Wolves in the 2004 Conference Finals. And that was as close as that group would ever come to a ring.

For Latrell, that was basically it. He played one more year in Minnesota, then entered a contract stalemate with the Wolves—he infamously told the press he wouldn’t take a minimum contract because he had children to feed—and despite some reported interest in later years from the Dallas Mavericks and San Antonio Spurs, he never played another NBA game after ‘04.

To this day, Sprewell’s name pops into headlines every so often, and as of yet it’s been for almost exclusively unfortunate reasons. All reported: His yacht was repossessed. He foreclosed on multiple homes. He owed $3.5 million in back taxes to the state of Wisconsin. He was sued by his ex-girlfriend. He was arrested for disorderly conduct.

It’s tough to know what of this is true and what were minor issues embellished by the media. He certainly doesn’t want to speak about it. It is true that Wisconsin makes public the names of anyone who owes the state more than $25,000 each year, and Latrell’s name is not currently in that database. His name is publicly listed on 14 court cases in Milwaukee since 2006, but most of them appear to be closed.

This much we know, too: As he did through the year he resided in pro basketball exile in between his Warriors and Knicks tenures, Latrell has spent the majority of his post-NBA life in Milwaukee. He went right back to playing ball at the YMCA in the mid-2000s, the same place he honed his skills in the winter of 1997. More recently he’s been frequently spotted in local bars, most notably Jo Cat’s Pub, a tiny bar in Milwaukee’s Lower East Side overtly designed for college-aged kids, with blaring pop music, some big-screen TVs, a bunch of Christmas lights and almost literally nothing else. Ask any random 20- or 30-strolling through Milwaukee’s Lower East Side if they’ve seen Latrell Sprewell around at all—as I did to a bunch in early April—and you’ll hear plenty of stories about seeing Spree around town, in Jo Cat’s or Ugly’s or Apartment 720 or Mi-Key’s. A Twitter search for “sprewell bar” results in dozens and dozens of people boasting about hanging at the same watering hole as Sprewell. The Kenny Powers vibes are perhaps a little too real.

That said, it’s evident, on the surface at least, that Latrell does not lack for self-awareness. He accepted some public attention for the first time in years in early 2016, starring in a Priceline commercial in which he jokingly gives terrible life advice to a little girl. It’s impossible to watch the ad without squirming at how on-the-nose the whole thing feels.

https://youtu.be/YvjWCAa7kO0

But if Latrell is particularly offended by his reputation, he seems willing to laugh it off, or at the minimum accept a nice-sized check to do so.

I mention to Van Gundy that if Spree really wanted to (and really needed the money), he could easily take one quick trip to New York City and pull in a ton of loot making appearances, doing meet-and-greets, autograph signings, all that. “I’ll say this: Even if he needed the money, he wouldn’t do it,” Van Gundy replies. “That’s just not who he is. He never tried to apologize for who he was. He was just a real guy.”

When he hears Sprewell’s name, Van Gundy doesn’t think about any negativity, though. He remembers the good times. There were lots of them, but a specific instance stands out:

One afternoon JVG walked into the SUNY Purchase gym—where the Knicks used to practice—and found Latrell shooting around with one of his young children. The Knicks’ coach stood around for a while, watching from a distance. “And in that interaction with his child, he was kind, and he was sweet, and he was patient,” Van Gundy says. “I think he had a lot more of that in him than people from the outside would ever begin to know.”

That is, at least in part, Latrell’s fault. But maybe it’s ours, too.

—

Adam Figman is the Editor-in-Chief of SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @afigman.

Photos via Getty Images.