Long before the Thunder touched down in Oklahoma City, before KD, Brodie, and the Beard ever donned the blue and orange, it was Chris Paul who was the face of OKC sports.

Just two months after the New Orleans Hornets made the 6-1, All-American point guard from Wake Forest the fourth overall pick in the draft, Hurricane Katrina swept through New Orleans and the Gulf Coast on August 29, 2005, causing catastrophic damage and mass casualties.

“I’ll never forget being home in North Carolina and waking up and looking at the news,” Paul recalled in an interview on the Knuckleheads podcast in 2020. “We ended up relocating to Oklahoma for two years.”

Chance, misfortune and—some might argue—fate opened the door for a city that nobody thought could support something that otherwise seemed so out of their league.

“It is one thing to sort of dream and hope for major league status, but we really didn’t do a whole lot of that,” said Berry Tramel, a long-time sports columnist for The Oklahoman. “It just sort of landed in our laps.”

“We were all homeless.”

Michael Thompson, the former New Orleans Hornets Director of Corporate Communications, remembers the time vividly. “My home was under 10 feet of water.”

While the majority of players were not in Louisiana when the storm hit (training camp wasn’t scheduled to start for another month), many of their and the Hornets staff’s homes were destroyed, like tens of thousands of other New Orleans residents’ homes.

As staff members dispersed across the country for safety, the immediate future of the franchise was uncertain. With training camp set to open five weeks after the storm, and the regular season a month after that, decisions had to be made, and made swiftly.

Candidates for temporary relocation destinations spanned coast to coast, even spilling internationally. Kansas City, Las Vegas, San Diego, Vancouver, Montreal, Tampa, Nashville, Anaheim, Pittsburgh, St. Louis and even San Juan, Puerto Rico, were all reportedly considered.

Oklahoma City (pop. 550,000 in 2005) didn’t initially fit the profile. Sure, college sports were colossal in the state, but other than triple-A baseball, there was no major sports team at the time. In the late ’90s, the city submitted a failed bid to acquire an NHL expansion franchise. But OKC already had a turnkey arena in the Ford Center (now Chesapeake Energy Arena), a $90 million modern venue built in 2002 specifically to attract an NBA or NHL franchise. OKC was also within relative distance (700 miles) of New Orleans and teams within the Southwest Division.

“We never even sniffed the NBA or thought of the NBA as a possibility until the hurricane,” said Tramel. “A couple of civic and city leaders with some foresight hatched the idea and made it work really quick.”

By September 21, 2005, eight days out from training camp, the franchise held a press conference announcing they would play 35 of their home games in OKC and the remaining six in Baton Rouge. The New Orleans/OKC Hornets were official.

The first meeting of the day would start at 6 am. A group of team officials would attend an event like a rotary club breakfast, make a pitch and walk out with 50 Hornets season tickets sold. They would repeat this five or six times at different organizations. At 11 pm, 60 Hornets employees would have their daily staff meeting from a ballroom at the downtown Sheraton that would spill into the next morning. This routine went on seven days a week for a month.

“Those four weeks, we had to accomplish in every 24-hour period what a normal expansion franchise would do in a month,” Thompson said. “The season was going to start whether we’re ready or not.”

The players also rushed to get situated. Unlike playing in New York City or Los Angeles, players took advantage of mid-sized city pricing. Chris Paul paid $750 in rent to share a home in Edmond with his brother, while JR Smith, his closest friend on the team, lived down the street. Desmond Mason, who had starred at Oklahoma State in the late ’90s, served as the official ambassador to the city for the team, helping them get acclimated to the nuances of Midwestern living.

“I was the guy that kind of kept everybody comfortable when all the tornado sirens went off or when there was golf-sized hail and guys were freaking out not knowing what to do,” said Mason, who was traded to the Hornets right before the season.

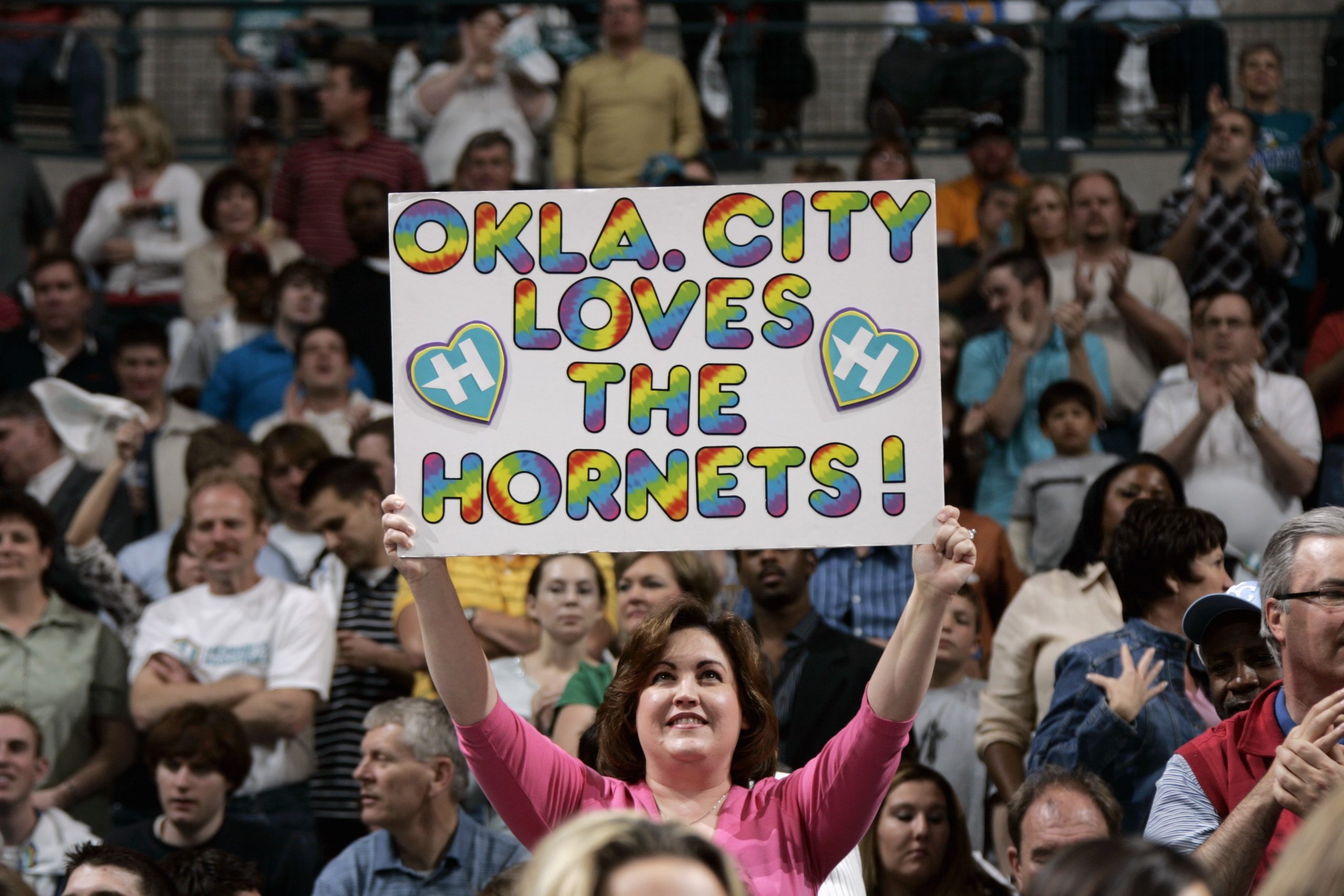

Easing the transition for the Hornets organization was the immediate support from the basketball thirsty community.

“The thing I remember most was just the excitement that the Oklahoma City Hornets brought to town,” said Trae Young, who grew up in Norman, OK. “I was already in love with the game prior to their arrival in OKC, but that definitely added fuel to the fire.”

Young was just 7 years old when the Hornets arrived, but for older locals, the presence of the team was an opportunity to bring joy and a fresh identity to an area that endured horrific tragedy themselves. In 1995, the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City was bombed by a domestic terrorist, killing 168 people, including children.

For a franchise that was in the process of healing from Katrina and a city that could relate, basketball became another common bond between the Hornets and OKC.

“The least we could do is go out and play as hard as we can,” Paul told reporters after the team’s first game, a sold-out home victory over the Sacramento Kings. “We feel like we owe a lot to this city and the state of Oklahoma for accepting us.”

18 and 64.

That was the record (second-worst in the League) of the Hornets the season before. They played to half-empty stands (literally, the Hornets were dead last in attendance) at the New Orleans Arena. Only eight players from that 2004-05 team returned.

“We thought they would stink,” said Tramel. “A lot of people speculated that because the Hornets were billed as a temporary team, that people would really come out just to watch the other teams and their stars.

“But within no later than two or three games, the whole city just went ga-ga over the Hornets themselves.”

The team turnaround started in training camp. Coach Byron Scott had his blend of misfits do military-type conditioning drills, ensuring effort could compensate for a lack of talent. They stuck as a unit. At home they bowled together, on the road they ate together. It was a college-team atmosphere.

Donning Hornets jerseys with an “OKC” patch on the upper right shoulder, that camaraderie extended onto the court. Even though the team hovered around .500 most of the season, they were suddenly competitive, particularly at home where they had a 24-17 record.

“We caught a lot of teams off guard,” said Mason. “They thought that we were just gonna roll over and die.”

All of sudden the team started to forge that identity. There was that tenacious defense. There was Chris “Birdman” Andersen, who would thrill the crowd with his dunks. David West’s toughness and methodical mid-range game. Speedy Claxton, the emerging sixth man. And, Smith, who showed flashes of brilliance, with high flying dunks and deep threes—but often in Scott’s doghouse.

But the catalyst and leader of the team was the diminutive but tough-as-nails rookie who was putting up Jason Kidd-esque numbers.

“Chris had that leadership quality from the jump,” said Mason, who called Paul the best point guard he had ever played with. “He was always a guy that was vocal but also had respect because he had veterans on the team. He could see everything on the court, he was so beyond his years.”

Also fueling the team, perhaps in a greater way than even Paul could, were Oklahomans in the stands. They treated even preseason games like Game 7s.

“Crowd was crazy the first time we went there,” said Quentin Richardson, who played for the Knicks at the time. “[The OKC fans were] at the game early and visible during warmups. But once the game got going, we saw that they were more like a rowdy college crowd as opposed to most arenas in the NBA.”

The Hornets were also the biggest show in town off the court. They were rockstars. Players received free meals at upscale steakhouses and loaner cars from luxury dealerships. Coach Scott got free rounds of golf around town. Fans wore Paul jerseys and kids got haircuts like Birdman.

The Hornets also had a responsibility to the city and state that they left. On top of the games in Baton Rouge, they would return a few times per season to play in New Orleans. They would help build homes and raise money for Habitat for Humanity to help rebuild their city. Everybody, including fans in OKC, knew that they would eventually return to Louisiana.

Despite a strong start that inaugural season, the Hornets went on a freefall the last two months, losing 15 of their last 22 games.

“I think we lost to Utah the last week or two of the season when we were [mathematically] eliminated [from the playoffs],” said Claxton. “I remember in a locker room feeling crushed and I actually think I shed a tear or two.”

The Hornets finished 38-44, a 20-win improvement from the season before. The next season, a team that now featured Tyson Chandler, Bobby Jackson and Peja Stojakovic, OKC was on the fringe of an 8-seed, but again, fell a few games short.

After two years, it was time to return to New Orleans.

The success of the Hornets in town (they generated $65 million in revenue for the city in year one) encouraged the inception of the Thunder in 2008, when the Seattle SuperSonics were moved to OKC. In 12 seasons, the Thunder have reached the playoffs 10 times, the conference finals four times and made their sole NBA Finals appearance in 2012.

Paul’s own Hall of Fame résumé is also well chronicled: Rookie of the Year; 11-time All-Star; Gold medal in Beijing; Lob City; and as we went to press, he was in the process of making a deep run with the Phoenix Suns in the 2021 postseason. In 2019-20, of course, Paul’s career went full circle, as he went back (and thrived) in the city where it all started, this time for the Thunder.

“I think it’s truly special that CP [was] able to return to the city that he helped put on the map basketball-wise,” said Young. “It’s only right.”

Paul became an All-Star and led the Thunder to the playoffs. Two months after the Thunder were eliminated by the Rockets in the bubble, Paul was traded to the Suns.

Although Paul’s return to his OKC roots in 2019 undoubtedly brought nostalgia, there are limited proof points of their existence around town or even in the official books (literally, the NO/OKC official records aren’t recognized in the Thunder, Pelicans or Hornets’ media guides). However, those who lived it will tell you that the Oklahoma City Hornets were pioneers.

“It’s a great feeling to know that I was part of something special,” said Mason, who also played for the Thunder in 2009 and currently lives in Oklahoma City. “It was a tragedy that made that happen. Without Hurricane Katrina, the Hornets never leave New Orleans. And if that never happens, the Thunder never show up, in my personal opinion.”

But beyond business and what ifs, the OG Oklahoma City team conjures up a more humanistic legacy for Mason.

“I always get these little snippets that come across my social media that have the hashtag #OKCHornets. It just kind of sparks all those feelings of great times all over again.”

Gerald Narciso is a Vancouver-based freelance writer, whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Bleacher Report, and Sports Illustrated. A native of Salt Lake City, Utah, Gerald was cut from his high school varsity basketball team despite being able to effortlessly dunk a tennis ball. He now plays in corporate leagues where 20-year olds run circles around him. Follow him on Twitter @geraldnarciso.

Photos via Getty Images.