Bill Russell passed away on Sunday at the age of 88. Our condolences are with his loved ones during this time. Back in August of 2020, the NBA legend contributed a powerful essay in SLAM’s special issue devoted to social justice, where he detailed his fight against racism throughout his life.

A little more than a hundred years ago, when my dad was born in Louisiana, there wasn’t a school for Black children to go to. So, my grandfather got some people together to raise money to buy lumber to build a school along with the $53 needed to hire a teacher for a year. They bought the lumber and then went to get the wagon and the mules to pick it up and take it to the building site, and the white guy at the lumberyard asked what they were going to do with all that lumber. One of the men told him they were going to build a schoolhouse, to which he replied, “Those kids don’t need to know how to read to pick cotton,” and he refused to give them the lumber and further, he refused to give them their money back. Now my grandfather wasn’t going to accept that, and he said, “Well, if you aren’t going to give us the lumber and you aren’t going to give us our money back, then I suppose the third option is that I’m going to have to kill you,” and he went to get his shotgun. Well, the guy at the lumberyard changed his mind pretty quickly after that and decided to go ahead and give them the lumber.

Years later, in the early ’40s, when I was 7 or 8 years old, my father drove us to the icehouse to get some ice, and the white attendant ignored us while he visited with another white man. We waited for 20 minutes or so, and then the white man drove off. I thought the attendant would come to serve us as we were next in line, but another white man drove up and the attendant went to serve him instead. My father started to drive off, but the attendant ran toward the car and shouted at my father, whom he had the audacity to call “a boy,” and said that he better stay put or he’d shoot him. My father wasn’t going to be spoken to or treated like that, and he calmly picked up the tire iron that was laying on the floor on the passenger side and got out of the car. That attendant turned and ran into the icehouse as fast as he could. My father got back in the car, cool as could be, like nothing had happened.

What I learned from these events and the many other events that I saw or experienced like them was twofold: First, that you must make the price of injustice too high to pay, and second, that such events are not reflective of your character, but of the character of the perpetrator. I was also lucky enough to have parents who loved me. Their love was formative because I figured if they loved me, I must be worth loving, and as a result, I’ve never cared about being liked––only respected. It is their love that allowed me to set my own standard, to disentangle my self-esteem from the beliefs of others. This skill would prove invaluable throughout my life, and especially my career as a professional basketball player.

I have long maintained that it is more important to understand than to be understood. What I understood was that in my junior year of college in 1955 at the University of San Francisco, my team went 28-1. We won the Final Four, I was a First Team All-American, I averaged 20 points and 20 rebounds (and a lot of blocked shots, which they didn’t count at the time), and was named the NCAA Tournament Most Outstanding Player. Yet, at the Northern California sports banquet, they picked another player, a white center with a less impressive set of accomplishments, as Player of the Year. I could’ve been hurt by that but rather, I simply dismissed that award.

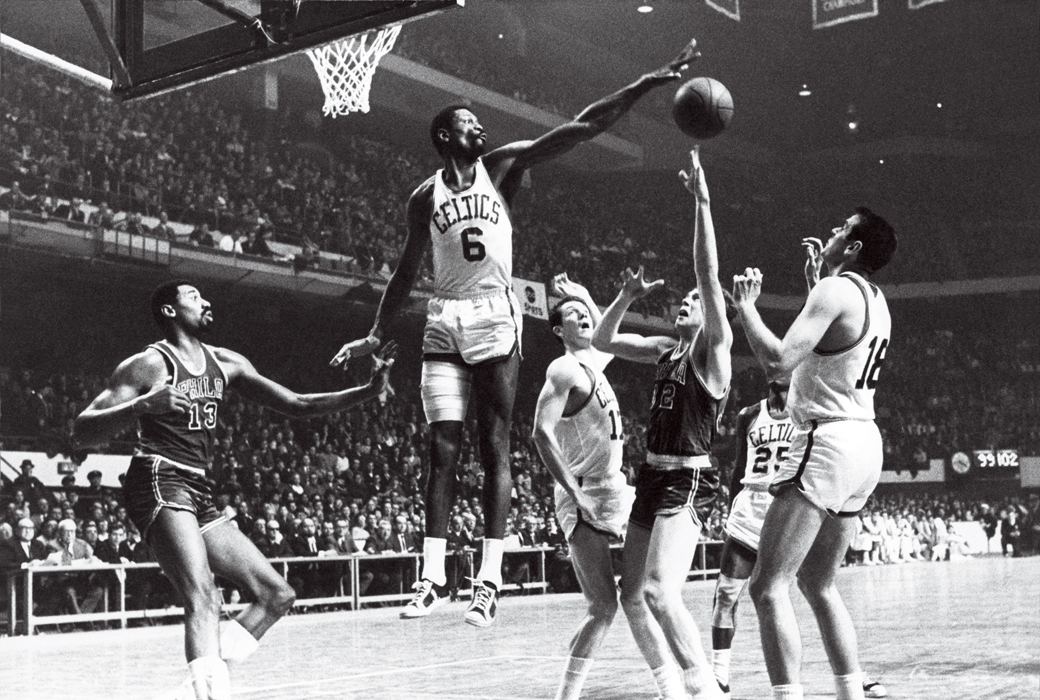

In December of 1956, already two months into the season because I was competing in the Olympics, I began my career as a Boston Celtic. The team had had a Black player before me, Chuck Cooper, but when I arrived, I was the only Black person on a team of white guys. The Boston Celtics proved to be an organization of good people––from Walter Brown to Red Auerbach, to most of my teammates. I cannot say the same about the fans or the city. During games people yelled hateful, indecent things: “Go back to Africa,” “Baboon,” “Coon,” “Nigger.” I used their unkindness as energy to fuel me, to work myself into a rage, a rage I used to win. A few years later we had a handful of Black men on the team. There were still only about 15 Black men playing in the League, so I complained about there being a quota, a cap to how many Black players could be on the team. That complaint led to change. The Celtics also ran a poll asking fans how they could increase attendance. More than 50 percent of the fans polled answered, “Have fewer Black guys on the team.” I refused to let the “fans’” bigotry, evidence of their lack of character, harm me. As far as I was concerned, I played for the Boston Celtics, the institution, and the Boston Celtics, my teammates. I did not play for the city or for the fans.

Playing basketball during Jim Crow meant there were many times when bigots wouldn’t serve us. In 1961, before we played an exhibition game in Lexington, KY, some of my teammates and I were refused service because of the proprietor’s bigotry. We walked out and boycotted the game. But such injustices took a toll. I’ll never forget having to drive through the day and night to get some place, ignoring the cries of my still young children, because there was no place to stop to eat or rest, no hotel or restaurant that would accept our Blackness. None of my medals or championships could shield my children from White Supremacy. All I could do was try to instill in them the love and pride my parents instilled in me and hope it would be enough.

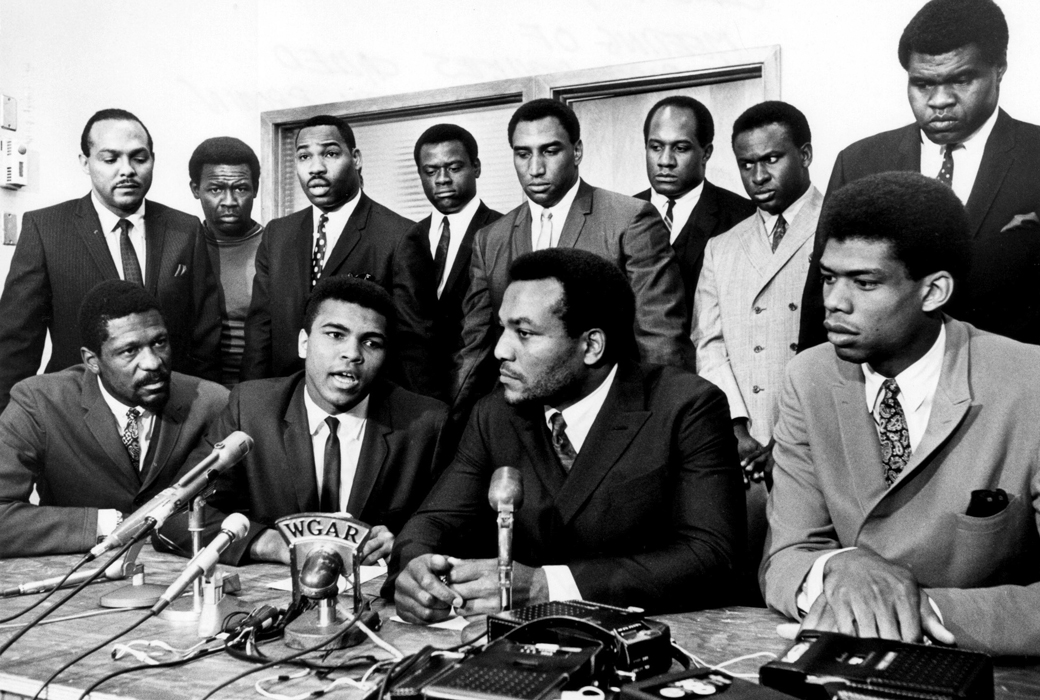

In the 1960s, I tried to move to Wilmington, MA, but nobody would sell me a house. So, I moved my family to Reading, a predominantly white town 16 miles north of Boston. Bigots broke into the house, spray-painted “Nigga” on the walls, shit in our bed. Police cars followed me often. I looked into buying a different house in a different neighborhood, but people in that neighborhood started a petition to persuade the seller not to sell to me. Around this same time Medgar Evars was murdered by the KKK. His brother, Charlie, asked me if I would do a series of integrated basketball clinics for children, which I did. I marched in Washington, supported Ali. After that, the death threats started coming. I said then that I wasn’t scared of the kind of men who come in the dark of night. The fact is, I’ve never found fear to be useful.

Way back in 1942, when I was 9 years old, five guys ran by me while I was sitting on the steps outside the projects in West Oakland, where my family had just moved to from Monroe, LA. One of these guys slapped me, so I did what any 9-year-old would and I went and told my mother. My mother said, “They did what?” and grabbed me and grabbed the keys to the apartment and we set out to find them. I didn’t know what my mother was going to do exactly, but I was confident that she was going to take care of it.

Eventually we found the guys and my mother turned to me and said, “OK, now you’re going to fight every one of these boys––all five of them––one at a time.” I don’t know what I was expecting her to do, but it surely wasn’t that. I wasn’t exactly scared of these boys, but I wasn’t particularly eager to fight them. However, I knew better than to argue with my mother, so I fought. Many years later people would talk about how I should’ve been a fighter, but I never really was good at it. That day was no different and I lost three of the fights and won two.

On the way home, my mother told me that it didn’t matter whether I won or lost those fights, but what mattered was that I stood up for myself. Maybe I lost my sense of fear when I fought those boys that day, maybe fear isn’t something a Black kid in the projects could afford to pay attention to. My mother went on to tell me that I should never pick a fight with anyone, but that I should always finish the fight I was in. I’m 86 years old now and I figure I’ve got another fight to finish.

Yet another Black man, George Floyd, has been added to the list of the thousands of Black people killed by police brutality, yet another life stolen by a country broken by prejudice and bigotry. When I was a kid, I learned to run away from the police because they’d arrest you, or kick you, or kill you if you were Black. I remember when my brother Charlie started a little shoe shining business. He was 12 years old and lots of kids shined shoes for money at the time. The police arrested Charlie, I think for not having a peddler’s license, and I was struck by the unfairness of it. The white boys were never arrested for shining shoes, but the Black boys were. My brother had a record because of it, and that record could be used later to show he was a troublemaker and to excuse the behavior of a police officer who chose to abuse his or her authority.

As an adult, the police would follow me around Boston, Reading, Mercer Island, Los Angeles. Early in the 1970s, I was pulled over by two cops while driving down Sunset Boulevard in a Lamborghini. I asked why they pulled me over. One of the officers said they had a report of a stolen car that looked like mine. I asked the officer exactly what kind of car was reported stolen. He looked almost panicked as his eyes rapidly searched my car, looking for a clue. He couldn’t find one because the car only had a small emblem on the front of the hood. I again asked what kind of car was reported. Fumbling, the officer then told me that I looked like an armored car robber and told me to get out of the car.

I raised my hands, both of them, as high as I could. One of the cops told me to put my hands down. I refused. Again, he asked me to put my hands down. A crowd formed on the sidewalk, because it’s difficult to ignore a very tall man standing with his arms straight in the air. I refused. I said something like, “No, I’m not going to put my hands down because if I do you’ll say I went for a gun and shoot me.” I wasn’t wrong. I turned toward the crowd and yelled, “Don’t shoot,” as I began to, very slowly, reach for my wallet. I gently dropped the wallet on the car and shot my arm back in the sky.

The officer again asked me to lower my hands and I refused again, and shouted, “It’s stop-the-nigger-in-the-expensive-car time.” The police officers rifled through my wallet. Then the other officer asked, “Are you the same Bill Russell who played for the Celtics?” as the crowd began to murmur. The officers’ tone shifted at the realization. They laughed and apologized. All of a sudden, it was a “routine mistake.” All of sudden, I didn’t look like a thief. All of a sudden, my Blackness was excused.

You don’t need me to tell you that racist police officers are a problem, and you don’t need me to tell you that such racism is pervasive throughout not just police departments, but every American institution because every American institution was built on the backs of Black and Brown people. I recently wrote an article for the Boston Globe referencing “Strange Fruit,” the song Billie Holiday made famous. This week, reports of Black bodies hanging from trees have begun to surface. History must not repeat itself.

But what can we do about it? Racism cannot just be shaken out of the fabric of society because, like dust from a rug, it dissipates into the air for a bit and then settles right back where it was, growing thicker with time.

Police reform is a start, but it is not enough. We need to dismantle broken systems and start over. We need to make our voices heard, through multiple organizations, using many different tactics. We need to demand that America gets a new rug.

In many ways, I owe my happiness to the love my parents gave me. Their love gave me the confidence to simply be me: a proud Black man, fair, and I believe, dignified.

Of course, as too many Black and Brown mothers will tell you, all the love in the world can’t keep a Black child from being murdered.

More dust in the rug.

Our children deserve better.

All of them.

100 percent of proceeds from SLAM’s new issue will be donated to charities supporting issues impacting the Black community. Grab your copy here.

Photos via Getty Images.