The New York Rens could really hoop. The team’s all-time record was 2,588-539. They won 88 straight games in 86 days during the 1932-33 season, finishing that year with a 120-8 record. They won the first pro basketball championship in 1939, beating the Oshkosh All-Stars.

But what they started in Harlem, on 138th Street and Adam Clayton Powell Jr Boulevard, is much bigger than just what happened on the court. The Rens were the first all-black professional basketball team. They were brave pioneers, busting down doors in the face of racism and adversity to lead the way for African-American athletes across the country for generations to come.

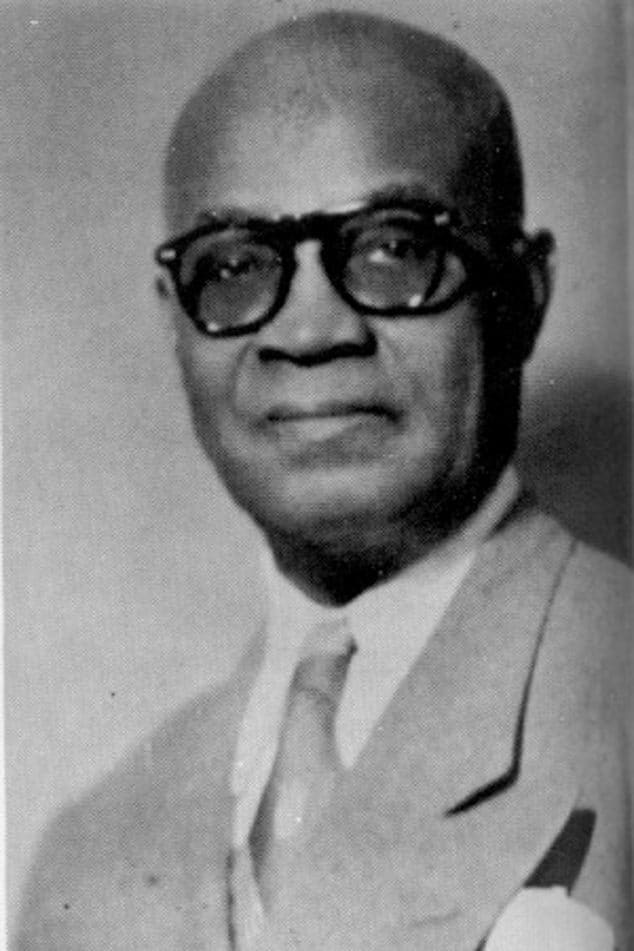

Bob L. Douglas founded the Rens in 1923 and eventually became the first African-American inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. But before that happened, he set in motion a visionary plan, one predicated on total on-court domination. By striking a deal with the owners of the Harlem Renaissance Casino, Douglas was able to create his own team with a place to play (The Renaissance Ballroom). By thriving on the floor, Douglas knew how much of an impact that team could have on young people.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was only two years old when Douglas’ ownership of the Rens ended in 1949, but he’s always understood the importance of the program and Douglas’ contributions to basketball.

“Bob Douglas was the first black man to own a basketball team,” he said, via The Undefeated. “Not just any team, but the greatest team of the time. The early rivalry with the Original Celtics and Harlem Globetrotters gave basketball exciting teams to support. The possibilities for business success as owners of professional sports franchises is the heart of Bob Douglas’ story.

“Douglas was ahead of his time because as a black man, he was not allowed to own a major sports franchise. He and his team faced so many challenges, mostly with racism against his team. His courage in keeping the team together while at the same time running his club places him ahead of this time.”

Douglas and the Rens toured the United States, overcoming constant racism and poor traveling conditions to continually destroy anyone they matched up against. They played the game together, working in concert on defense and whipping the ball around the perimeter. No matter what was thrown at them, Douglas and his team just couldn’t lose.

“To this day, I have never seen a team play better team basketball,” said Hall of Fame coach John Wooden, who played against the Rens when he was a member of the barnstorming Indianapolis Kautskys during the ’30s. “They had great athletes, but they weren’t as impressive as their team play. The way they handled and passed the ball was just amazing to me then, and I believe it would be today.”

“I tried to spread the word [about Douglas] with my book and documentary, On the Shoulder of Giants,” said Abdul-Jabbar. “I did both to make people aware of the Rens’ contribution to basketball because it’s important that we honor those pioneers who made this billion-dollar industry possible. It’s also important that we recognize the people of color who did so much but that history deliberately ignored. The best way to do this is to keep their names in front of the public in textbooks, basketball events, and with sports memorabilia the way we do with other pioneers in sports history.”

In order to fully respect the Rens, their legacy has to be looked at both on and off the court. 88 consecutive wins is impressive, there’s no question. But 88 straight wins in the face of unwavering discrimination is a miracle.

The Rens conquered race riots. They were courageous when they faced threats of violence. They held firm when white businessmen denied them the right to play in the American Basketball League in 1925. They just kept winning.

They monopolized the game for nearly two decades before finally getting a chance to put everything together. Their win against the Oshkosh All-Stars, an all-white team, in 1939 gave them the distinction of capturing the first-ever professional basketball championship—proving yet again that there was nothing that could stop them.

The Rens program was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1963, as a final tribute to one of the greatest squads to ever play. The team re-formed in 2012 as an AAU program and has been a home for players like Rawle Alkins and Hamidou Diallo, both of whom made it to the NBA. The Rens’ current star is point guard Jalen Lecque, a four-star recruit that’s committed to play at NC State in the fall.

Douglas and the original Rens, according to Abdul-Jabbar, would be happy about their legacy and how far the game has come.

“Bob Douglas would be very pleased with not only how much the game has developed athletically but also with the number of African-Americans involved in the sport,” said Abdul-Jabbar. “He would be delighted with the status of black athletes, not just the money they are making but with their influence on our culture.”

—

Max Resetar is an Associate Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Photos via Black Fives Foundation.