As basketball’s all-time scoring leader, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar knows a thing or two about breaking and owning records.

The records Abdul-Jabbar has set—in addition to the 19 NBA All-Star appearances, six championships and six MVP awards—are certainly important to him, but the main reason they are important doesn’t connect directly to basketball. In an essay written for The Guardian last summer, he noted a Muhammad Ali quote that has always stuck with him:

“When you saw me in the boxing ring fighting, it wasn’t just so I could beat my opponent. My fighting had a purpose. I had to be successful in order to get people to listen to the things I had to say.”

For Abdul-Jabbar, another motivation to become an all-time great on the hardwood was to build a platform for himself off of it. Most of his records will eventually be broken, and he’s OK with that.

“All sports records will inevitably be broken, but the day after they are, the world won’t have changed,” he wrote. “But every day you speak up about injustice, the next day the world may be just a little better for someone.”

Witnessing the Harlem race riots as a child, Abdul-Jabbar was exposed firsthand to the prevalence of police brutality and racial inequality in the United States and became determined to do something about it.

Just as athletes like Ali, Jim Brown and Bill Russell inspired him to take a stand, so did the likes of non-athletes like Malcolm X.

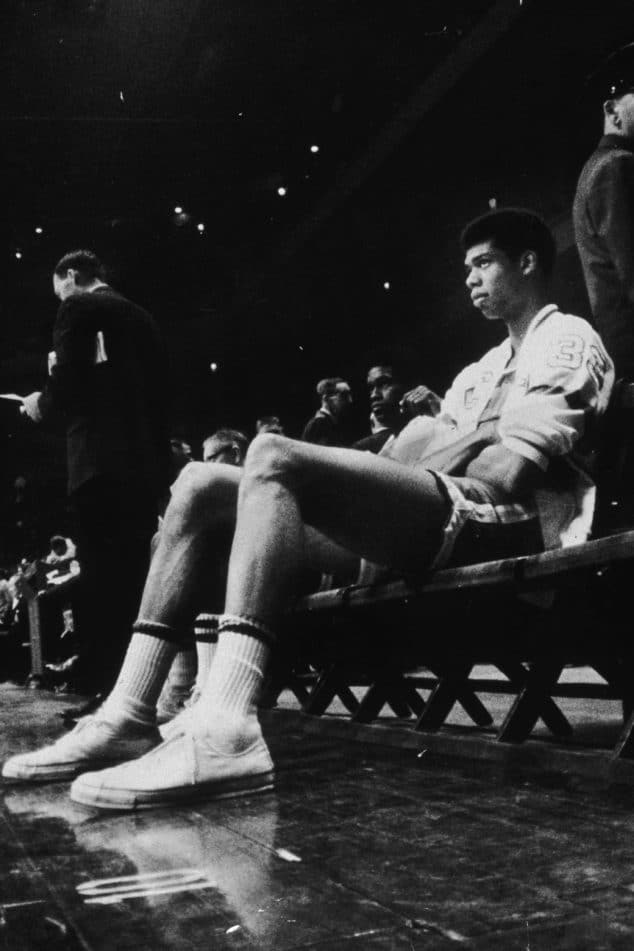

Abdul-Jabbar protested inequality when he boycotted the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City—he didn’t want to win a gold medal abroad only to be refused service at a restaurant in his hometown.

“Somewhere each of us has got to take a stand against this kind of thing,” he stated. “This is how I make my stand—using what I have. And I take my stand here.”

He held firm in his decision not to play, also citing the fact that he would have to miss class as rationale.

“I was torn because I knew that joining the team would signal that I supported the way people of color were being treated in America—which I didn’t,” Abdul-Jabbar said. “But not joining the team could look like I didn’t love America—which I did.”

A college student and dominant star on the UCLA basketball team at the time, Abdul-Jabbar received backlash in the form of hate mail and vicious threats.

Through the years, the NBA veteran has remained heavily focused on outreach. Knowing the path to professional sports is slim, he’s encouraged young African-Americans to also pursue more conventional, education-based passions.

In 2012, he published a children’s book highlighting African-American greats that made names for themselves off the hardwood called, What Color Is My World?: The Lost History of African-American Inventors. It became a New York Times best-seller.

A large pillar he’s had to topple has been dispelling deep-rooted stereotypes that he believes have led many African-Americans to feel more obligated to seek out the playing field than the classroom.

“The whole idea Europeans had that Africans could not give anything worthwhile to the scientific disciplines got a foothold in people’s imaginations,” he said, in a discussion hosted by Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation. “It’s applied to every generation of young black Americans, and we have to change that.

“When they get heroes more like George Washington Carver and Thomas Edison, we have achieved ultimate success.”

Abdul-Jabbar has been writing books since the 1980s, but his efforts haven’t been limited to that. He’s spoken at panels and run events with the goal of helping children discover passions in STEM-related areas: science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

The Skyhook Foundation, named after Adbul-Jabbar’s signature basketball move, holds a free, week-long camp each year for fourth and fifth graders. Students from Los Angeles-area public schools go to the Clear Creek Outdoor Education Center in Angeles National Forest. While there, the curriculum allows inner-city kids to experience the outdoors in ways they’ve never been able to before.

“All the good jobs in the 21st century are going to be centered around science, technology, engineering and math. There’s no way around it,” Abdul-Jabbar told NPR. “If we can give kids an idea of where the jobs are and what they have to do to get those jobs, they can adjust right now.”

It’s important to Abdul-Jabbar that the camp also serves as a way to show kids that they don’t have to become entertainment icons to contribute to the world.

“So many of these kids, they want to be LeBron James or Beyonce or Denzel Washington,” he said. “They think that unless they’re a star, they don’t have anything to offer. That’s not true.”

The classroom was always an area of emphasis for Abdul-Jabbar; despite being one of the most heralded high school recruits of all time, he spent three years at UCLA and graduated with a degree in history before making his move to professional basketball.

A statue of Abdul-Jabbar was put up outside the iconic STAPLES Center in Los Angeles not too long ago, recognizing his accomplishments as an NBA legend. But to Abdul-Jabbar, what those accomplishments have enabled him to do beyond the court is the most important thing.

—

Ian Pierno is an Associate Social Media Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter.

Photos via Getty.