The streetlights have already been turned on, but it doesn’t matter. Classic Jay-Z songs blare from a cheap speaker and a group of old heads sit on a bench, angrily debating something about hoops. A few 5-year-olds run around behind them, dribbling with mini basketballs, while another pickup game keeps rolling along. From eastern Queens to the top of the Bronx, this is how it goes every day—New York City basketball never stops.

It starts early, around 10. That’s when the older players get there, nailing bank shots while wearing beat-up sneaks. There’s still shade in the morning and the breeze will saunter through the air every few moments. Parents stroll by with their kids, dogs get to galloping with wild grins. The smell of bacon, egg and cheeses mixes with the scent of the asphalt.

The vets calmly keep shooting, getting their reps in before games start in a few hours, before they sit to watch the action. They were the main attraction at one point, when the game was different but the park was the same.

The ballplayers arrive around noon. They take their time when they get there, making sure everyone knows they’ve pulled up. They give daps to just about everyone. It’s a lock that at least one person is about to make fun of them—hairstyles, sneakers, clothes, lack of on-court skills are the usual points of emphasis. That trash talk lasts all day.

The sun’s fully breaking through when the day’s first game tips off. It doesn’t take long for that trash talk to hit the court.

“He can’t guard me.”

“This dude’s feeb.”

“Get that shit outta here.”

And then the yelling. Foul calls, who touched the ball last, who actually called next. The weather gets hotter and the arguments get louder. On and off the court, a day at the park is about proving you belong and sticking up for yourself. There are people coming to take your spot, your reputation and your dignity.

From sun-up to sun-down, it’s time to perform. Basketball is more than a game here. It’s the soul of the city.

One time for Holcombe Rucker. He wanted to give the youth an environment to play ball and to improve their academics. “Each one, teach one” was his motto. He started a basketball tournament in 1950, played at a handful of courts around Harlem. The tourney blew up damn near instantly, and by the ’60s, Wilt Chamberlain, Julius Erving and Earl Monroe were among the players coming from out of town to do battle against NYC’s best.

Rucker started the wave, creating the idea of outdoor tournaments. It wasn’t long before the rest of the city caught on. Soul in the Hole in Brooklyn, West 4th Street in downtown Manhattan, Dyckman and Kingdome uptown, Hoops in the Sun in the Bronx and a whole bunch of other famous tournaments owe Rucker for changing the game.

Rucker’s the reason that New York City parks have become so important. Without his emphasis on going to the park, it wouldn’t have become a haven. In its heyday the Rucker tournament had people sitting on top of fences and watching from rooftops to see Erving, Connie Hawkins and Earl Manigault soar through the air.

And to keep it a buck, New York becoming the Mecca of Basketball can be traced back to Rucker’s vision to use the park as a way to improve lives and underline the influence of schooling. Players flocked to his tournament because they understood New York had the toughest ballplayers and that the park was the game’s realest stage.

Dyckman has taken over in the past few years, with up-and-comers like Isaiah Washington and Hamidou Diallo keeping the park all the way live. Appearances by numerous NBA players, including D’Angelo Russell, Kevin Durant and Kyrie Irving, whose game was cancelled because fans wouldn’t get off the court, have only bolstered Dyckman’s standing as NY’s current top court. Instead of sitting on fences, though, Dyckman crowds light up social media, posting the park’s one-on-one battles for the whole world to see.

There are over 500 outdoor basketball courts in the five boroughs. These blacktops have been the starting point for some of the game’s most influential talents. Kareem Abdul- Jabbar. Tiny Archibald. Chris Mullin. Kemba Walker. Rafer Alston. Bernard King. Lance Stephenson. Fly Williams. Joe Hammond. Pee Wee Kirkland. Tyron “Alimoe” Evans. Earl Manigault. Connie Hawkins. Long before they were dominating the NBA or crafting stories that would be passed down like basketball fables, they were just kids going to the park. Whether or not they knew it, they were on the fast-track.

These courts are about way more than just the game. They’re teachers, geared up in overdrive, putting people in positions to rapidly grow. They present real-life situations for all ages. More often than not, kids all around the city had a bunch of their firsts at the park. First kiss, first fight, first dunk, first time facing adversity without the help of their parents.

The park is a centralized spot, a place where the neighborhood gets scaled down in size and everything happens at once. There’s constant communication. Laughing with friends, talking to strangers, buying water bottles from buddy trying to make a couple of dollars. Adults reminisce on the good days, teenagers cause trouble and the little kids try desperately to get in on the fun.

Because the park is more than fun—it’s addicting. When summer comes, hands are permanently stained by the asphalt and the park’s aroma lingers on every piece of clothing. Life becomes a constant loop of wins and losses, of makes and misses, of sunshine and hoops.

—

RELATED

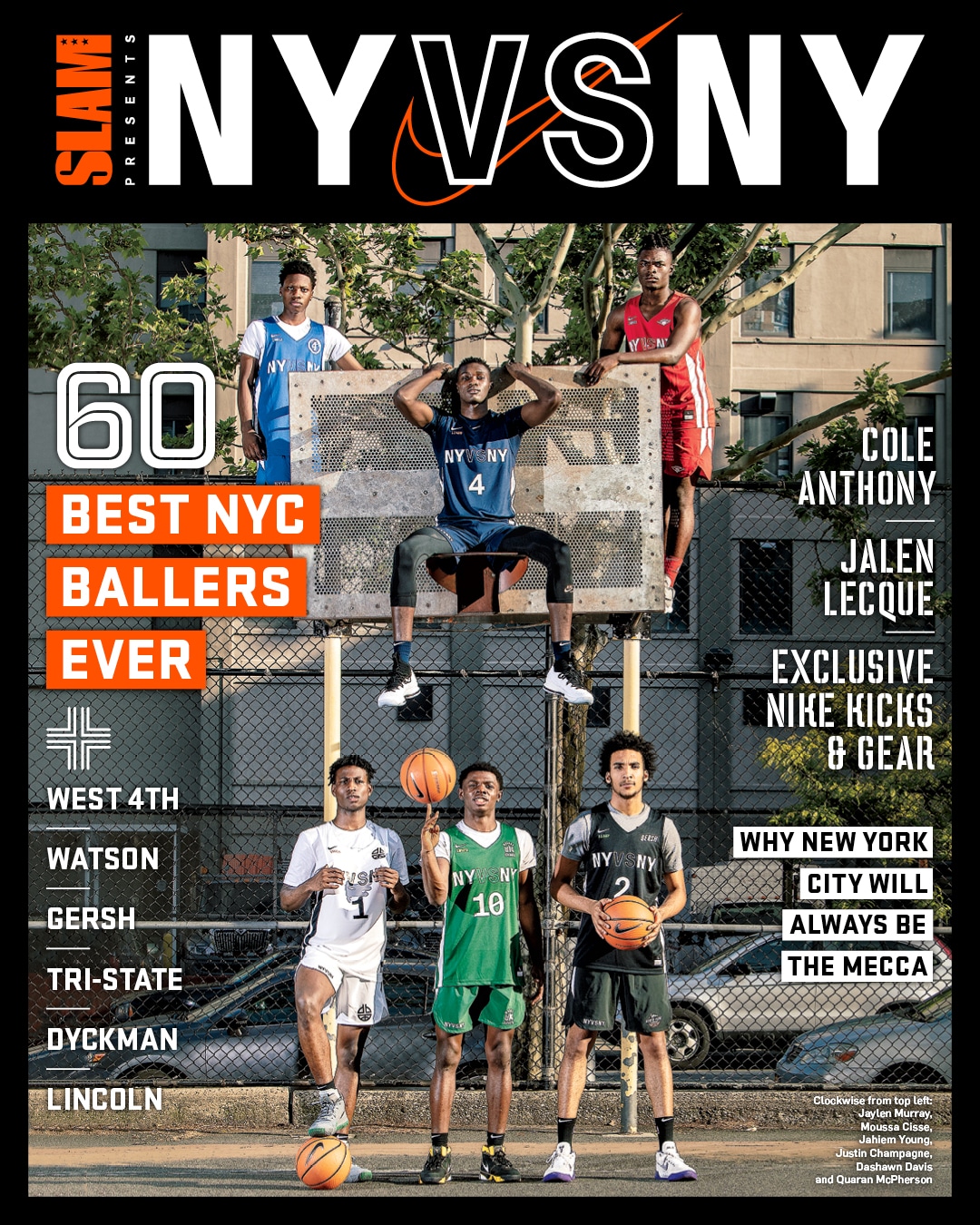

NY vs. NY Brings the Best High School Ballers in the City Together

Max Resetar is an Associate Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Photos by Jon Lopez.