1950. Harlem.

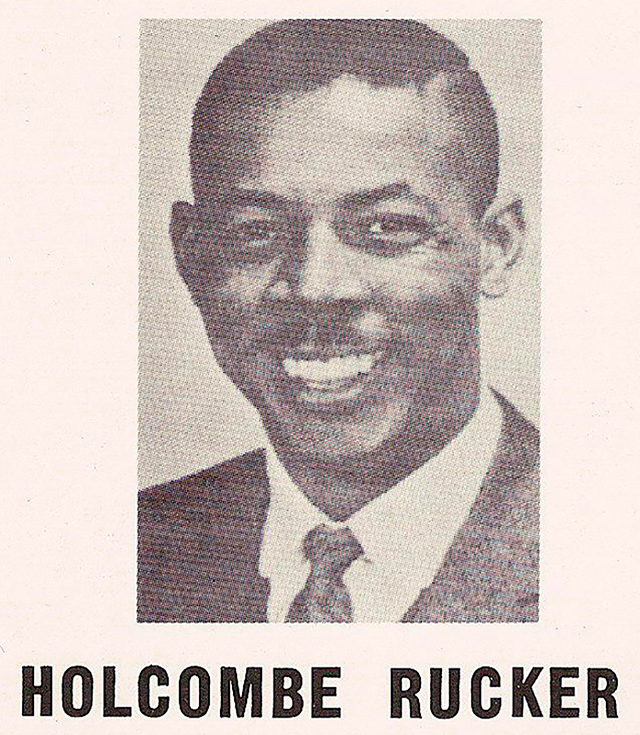

Fourth grader Bob McCullough, a pre-teen gang member of the Politicians, was raiding places at lunchtime, getting in fights every day and got arrested. His Saint Phillips Community Center (aka St. C) basketball coach, Holcombe Rucker, went to the 32nd Precinct…

“Hey Ruck, what you doing here?” young McCullough inquired.

“Checking up on knuckleheads like you!”

McCullough started doing his homework, became St. C’s top scorer, and in 1965 was the second leading scorer in the nation (right behind future Hall of Famer Rick Barry) with 36.4 ppg while at Benedict College.

“Rucker changed my life,” McCullough says.

In his years as an educator, coach and community activist, Holcombe Rucker helped hundreds of other Harlem youth get into better schools, using basketball as a tool for social change. Rucker’s most lasting legacy though was to invent the idea in 1946 of producing an outdoor youth league during the summer.

Believe it or not, one had never before existed—anywhere in the world.

During the 1950s, Rucker added college and pro divisions, and the very best ballplayers around participated: Ed Warner, the 1950 NIT Championship MVP for City College (CCNY) who weeks later led his squad to the NCAA Championship as well (the only team in history to win both in the same season); Sihugo Green from Duquesne, the 1955 NIT Championship MVP and No. 1 pick of the 1956 NBA Draft (ahead of Bill Russell); and future Hall of Fame inductees Connie Hawkins from Brooklyn and Wilt Chamberlain from Philly, just to name a few.

What Holcombe Rucker achieved was unprecedented and incomparable in any era. Ruck kept the game clock on his watch, score on a sheet of paper in his hand, and tournament schedule folded up in his back pocket. Oh, he also reffed! Meanwhile, traffic jams would form outside the court on 128th Street and 7th Avenue, which everyone in the hood affectionately called “Rucker Park,” to see playground legend Isaac “The Rab” Walthour dominate all the household names that tried to stand in his way.

Mr. Rucker laid down the blueprint for every organized outdoor summer basketball tournament/event/league, on any competition level that has ever been done since. He is The Godfather. The “Grand Daddy.” Not only did he create a platform for his community to enjoy the purest bball imaginable—for free—he also inspired generations moving forward to this day to want, or even better, dream, of one day playing in New York, outdoors, at the Rucker.

Unfortunately, Holcombe Rucker died of cancer in 1965. He was just 38.

A committee was formed to keep Rucker’s youth league moving forward, but without a pro division. McCullough, fresh out of college, had a different plan. “The creator of the Rucker was my surrogate father,” McCullough says. “I went to college and was drafted by the NBA [Cincinnati Royals—Ed.], all because I was a product of his guidance. He changed my whole life. And the pro division wasn’t going to be. I told [former St. C teammate] Freddie Crawford I will run the pro tournament.”

Crawford, the 26th pick in the 1964 NBA Draft who went on to play for the Knicks and Lakers, joined forces with McCullough. Imagine a tournament being run by two NBA-caliber players? What top talent would think twice about getting down with that level of co-sign?

In 1967, Crawford brought down fellow Knick Willis Reed, who was named Pro Rucker MVP. In ’69, half the Knicks’ squad, including starters Walt Frazier and Bill Bradley, played in the Pro Rucker. That very next NBA season, the franchise won its first league championship. Coincidence? Hardly.

In 1970, sportswriter Pete Axthelm published his book The City Game, which detailed for the first time to the rest of the world what exactly was going on up in Harlem, including the high-jumping legends of Earl “The Goat” Manigault and “Helicopter” Herman Knowings. The Rucker was no longer a treasured weekly community event. It was now on worldwide radar, and the stage was set for the ultimate explosion that took place the following summer.

In 1971, Julius Erving finished his college season at UMass averaging 26.9 points and 19.5 rebounds a game, but no one in New York had ever seen him play or had even heard about him. That is, until his first appearance at the Rucker…

In the immortal words of United Brooklyn coach Sid Jones (RIP): “My friend told me, ‘There’s a Rucker player who is better than Connie Hawkins and Elgin Baylor and can jump from the corner and dunk. They call him ‘The Claw.’”

Erving told the announcer that his nickname was “The Doctor,” and a playground legend, as big as there ever was or will be, was born. The NCAA didn’t allow dunking in that era, so with the crowd oohing and aahing to Erving’s above-the-rim assault on every play, even in the pre-game lay-up line, the Doc kept elevating his creativity to heights unseen in that day and age.

Erving went on to win championships, MVPs, scoring titles and dunk contests in both the ABA and NBA, and is generally considered one of the most influential basketball players ever. Basically, Erving was the Michael Jordan of the ’70s. And he completely credits his summers spent at the Rucker as the catalyst to his style of play.

How tough was the Pro Rucker in 1971? Erving’s teammate was Charlie Scott, who in ’71-72 led the ABA in scoring with 34.6 ppg, and eventually won an NBA chip in ’76 with the Celtics. With all that firepower, Erving and Scott couldn’t even win the ’71 Rucker Championship. The league MVP that season was Nate “Tiny” Archibald, who in ’72-73 led the NBA in both scoring (34.0 ppg) and assists (11.4), a feat never accomplished before or since.

Erving, Scott and Archibald all got buckets in the NBA, but in 1971, the high scorer at the Rucker was Richard “Pee Wee” Kirkland, a Chicago Bulls draftee who never played in the league but wrecked havoc while talking plenty smack at 155th Street and 8th Avenue. And the most notable scorer Uptown was Kirkland’s backcourt partner, Joe Hammond.

Nicknamed “The Destroyer,” Hammond’s rep at Rucker in 1971 earned him a try-out with the L.A. Lakers. According to legend, Hammond destroyed a young Pat Riley in a one-on-one, impressed Wilt Chamberlain during a shooting drill and was offered a contract, which he subsequently turned down.

That next season, the Lakers set the record for most consecutive wins (33) during the regular season (which still stands), went 69-13 (a record that wouldn’t be broken for 24 years) and won the NBA Championship. That’s how good they were. And they wanted Joe Hammond. That’s how good he was.

In 1978, Hammond scored 73 points at a Rucker game. Not even four-time NBA scoring champion Kevin Durant, who in 2011 dropped 66 at an EBC Tournament match, could break Hammond’s park record. Something special occurred in the ’70s…

“It can never be duplicated,” Butch Purcell declared. Purcell coached Erving, Scott and other Rucker legends in the ‘70s alongside future NBA analyst Peter Vecsey, and they won multiple championships. “Rucker came before West 4th, the Sonny Hill/Baker League in Philly, the Drew League in L.A. It was the only tournament in town. People came from all over the country to see.”

The influence of the Pro Rucker under McCullough’s direction post-1965 had layers that went way beyond what Holcombe had started innocently in the ’40s. The summer tournament produced future NBA referees and scorekeepers (some of whom are still active to this day), and became the first outdoor league that major corporate sponsors sought out. Major media outlets followed suit, including ESPN, who in 1980, their first year as a cable network, televised the championship.

The Pro Rucker even impacted street culture beyond basketball. “If you were involved in hip-hop or if you were involved with playing basketball, you had to come across each other,” Crazy Legs, the most recognizable b-boy the world has ever known, recounts. “Whether it be Dyckman, The Goat or The Rucker, there were always hip- hop jams going on.”

The Pro Rucker was also the first ever target for sneaker brands’ summer basketball marketing, loooong before AAU squads were bopping around the country. In 1977, PONY started handing out free sneakers from a car trunk, to the top players at ’55th. The strategy worked, as they earned quick relevance in the toughest city to crack for kicks. Rucker was the weekly showcase, the hypebeast.com platform but live, for hot releases people weren’t up on yet.

In honor of Holcombe Rucker’s contributions to Harlem’s youth as well as the global basketball community, the NYC Parks & Recreation Department officially dedicated the playground on 155th Street and 8th Avenue in his name. In Rucker’s physical absence, his loyal student Bob McCullough cemented his mentor’s legacy into the hallowed asphalt from 1965 until 1987, when McCullough ended the Pro Rucker and passed the torch, and park permit, to a young Greg Marius, tournament director of the EBC, which still holds court today. It was a kind gesture, one that would have made Mr. Rucker proud, since one of his favorite sayings was, “Each one, teach one.”

“It’s the 50th Anniversary of the Pro Rucker, but more importantly, it’s the 50th anniversary of Rucker’s death,” shared Butch Purcell. “Rucker brought the pro game to the youngsters in Harlem who could not afford to buy a ticket to see the Knicks at the Garden. And he did it for free.”

Holcombe Rucker is not enshrined in the Naismith Hall of Fame, yet his name is as recognizable across generations as any other in the sport. The game was birthed in Springfield but bball was raised in New York. Outdoors. In Harlem. At the Rucker. The NBA Vegas Summer League should pay tribute. So should any and every tournament, anywhere in the world.

images courtesy of Rucker Pro Legends