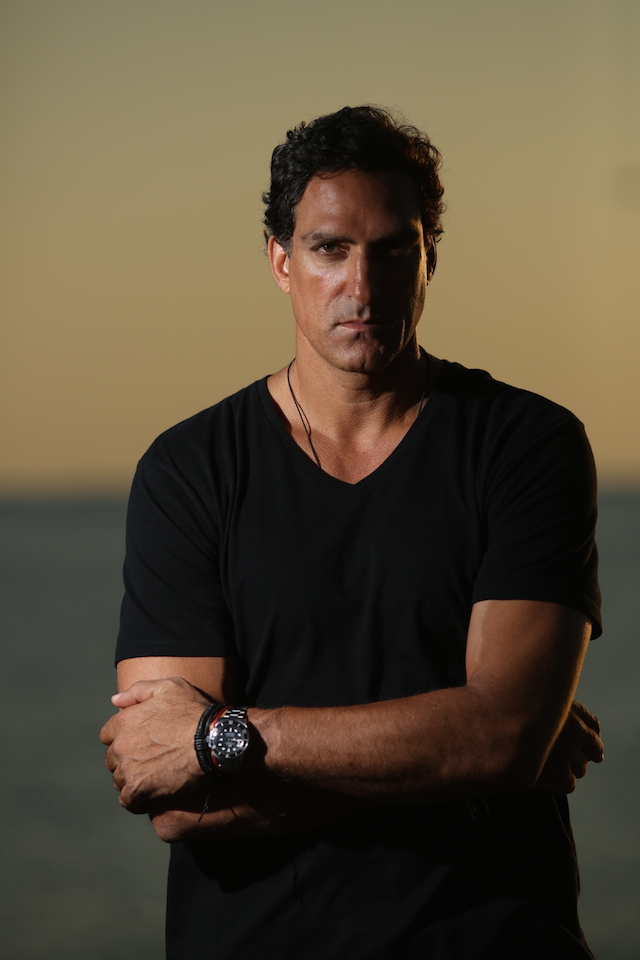

The first thing Rony Seikaly wants you to know is that this—being a DJ, a good one—is hard work. But he also knows you might not see it that way. He knows you might assume he’s just plugging in an iPhone, sliding a pair of Beats headphones over one ear while leaving the other uncovered. He knows that upon hearing that he’s a DJ, your mind might immediately wander to past maestros like Paris Hilton and that Pauly D guy from Jersey Shore and to the myriad other music-ignorant celebrities who at one point or another have turned the DJ booth into a joke.

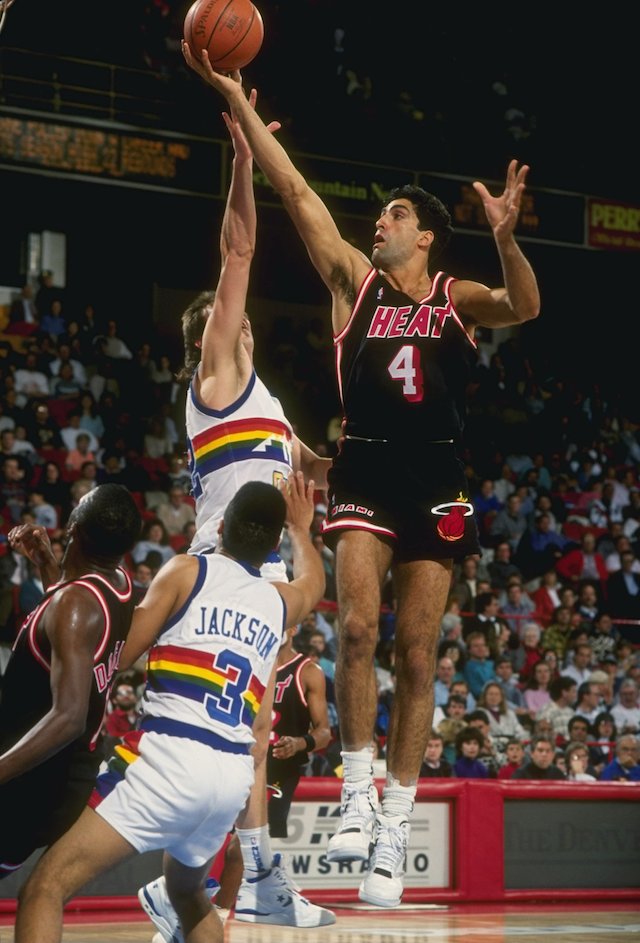

Rony Seikaly knows all this, and he knows that your initial reaction to learning that a former NBA veteran and ’89-90’s Most Improved Player is now a “world-famous DJ” is likely laughter. Which is why he wants you to know how wrong this line of thinking is.

“I come from the underground school where the object of the game is to play music nobody else is playing,” he says one fall afternoon over the phone from Miami. “Commercial DJs—they’re pretty much like jukeboxes. They play the hits, what people want to hear.

“Me, I’m trying to give someone the experience they’ve never had before.”

This is where all that hard work comes in. It takes new music to create that new experience, and to find that new music—what he refers to as “gems”—in an age where everyone has access to the same seemingly infinite music sharing platforms, Seikaly must parse through thousands of songs. Literally. By his own estimation he listens to around 3,000 new tracks every month, each lasting somewhere between five and 10 minutes. He spends between two and three hours every day alone in his home studio scouring the catalog of the meticulously organized folders he has saved on various hard drives. Some songs are pulled in full. Others—say, for example, one with a drop he likes but a weak rhythm—are skinned.

Eventually, all that music gets trimmed down. For his weekly SiriusXM radio show, he’ll put together somewhere between 20 and 30 tightly woven tracks. For his live sets, around 15.

“Being a good DJ is about your ear more than anything else, and that’s where the work comes in,” he says. “You could teach a monkey to mix music or play hits. It’s not hard. To me the hardest part is creating your own sound, your own vibe, so that any time you’re playing, people know, Oh, this is Rony’s style. That’s why, to do this, you have to love it. This hobby is a labor of love.”

So now you know: Rony Seikaly is not a stereotype. He’s a man following his passion. Or at least that was the plan. Then he lost sight of what had drawn him to this second career in the first place. That’s the funny thing about passion projects.

The project part is easy. Preserving the passion is hard.

Rony Seikaly has always loved house music. Want proof? How about the disco he built in his parents’ garage as a 14-year-old? He removed all their junk, painted the room black and lined the walls with foil paper because he couldn’t afford mirrors. Then he strung up a disco ball and installed two record players.

That was back in Athens, where he was raised after his parents moved to Greece from his native country of Lebanon. He and his friends were too young for the local nightlife so they spent evenings in the Seikaly garage instead. Students from visiting basketball teams were invited, too—and they were charged a $20 cover, which would be reinvested into upgrading the homemade disco.

Seikaly brought his love for house music across the Atlantic with him, first to Syracuse University and then the NBA, where he played 11 seasons and averaged 14.7 points and 9.5 rebounds per game. The first six of those seasons came for the then-expansion Heat, in Miami, which is where he makes his home today. MIA is also where his ear and burgeoning skills were refined, though at the time his NBA brethren had no idea.

“That’s the funny thing, I don’t remember him ever playing that music,” says Glen Rice, who played five years with Seikaly in Miami. “I don’t even remember him wearing headphones on the plane.” (Another memory Rice has of Seikaly: “The ladies loved him.” Adds another former teammate, Keith Askins: “Rony kept beauty around him. I’ll leave it at that.”)

Seikaly, now 51, says he tried introducing his music to teammates a few times but was always rebuffed and told to “turn that Euro shit off.” So he played for friends instead. They’d file into the mini-club he built in his new Miami Beach home that housed Seikaly’s late-night after-parties. One night, or, rather, early morning, sitting there with Sean “P Diddy” Combs and Erick Morillo, one of the world’s more popular house music DJs, Seikaly began playing one of his new mixes. This was back in 2005, five years after his retirement and right around the time of his divorce from his first wife, Mexican model Elsa Benítez.

Morillo, enjoying the beat, turned to Seikaly. “Whose music is this?” he asked. Seikaly told him. “That’s impossible,” Morillo said. Seikaly responded that it wasn’t. “What does a basketball player know about house music?” Morillo replied.

“Believe me,” Seikaly answered, “I’ve been listening to this music as long as you have.”

Over the next few months, Morillo brought more and more friends by the house. “Come on, Rony, play for them,” he’d plead. The gatherings continued to swell. Still, Seikaly remained hesitant.

“I didn’t want people to think that I was into this so that I could become a DJ,” Seikaly says today. “It was never about that, that was never the goal. It was always just about the music.”

But, eventually, he relented. He owned a club in South Beach and figured that’d be the perfect place for a test run, which turned out to be a resounding success.

Soon after he was playing at all the top clubs in the world. There were trips to New York and Las Vegas and Dubai. Around a year later he was invited to play on the island of Ibiza at a club called Amnesia, one of the most famous house music spots in the world. More than 5,000 fans came out to hear him play.

“It was just a surreal moment,” Seikaly says. “After that it really took on a life of its own.”

Seikaly compares music to all sorts of different hobbies, from meditation and yoga to reading and art. He uses the word “melodic” a lot. It’s soothing, hearing him talk about what music does for him, how he’s able to lose himself in the beat. It’s like listening to the voice on one of those pre-sleep relaxation tapes.

But all that grueling touring was hacking away at the love. Retirement from the NBA was supposed to bring about less travel—suddenly he was back to spending weekends running through airports and cramming his 6-10 frame into tiny seats on 5 a.m. flights. Sometimes he’d wake in his hotel bed unsure of what city he was in. He also had a new wife and a 13-year-old daughter (from his first marriage) waiting for him at home.

“It got to the point where it was feeling like a job,” Seikaly says. “For me, that’s not what I set out to do.”

He didn’t need the money. He had made north of $27 million in the NBA (per basketball-reference.com) and dabbled in real estate, too. And yet the more famous he got the more he got paid, and the more he got paid the more difficult he found it to turn down offers. He just hated saying no.

Then, this past October, he boarded a Wednesday flight from Miami for a New York show that night. On Thursday he played in Chicago. Friday in Montreal. On Saturday morning he went through customs again to do a gig in Detroit. He finished the stretch with a Sunday night show back in Miami.

Mentally drained and physically exhausted, Seikaly returned home. He collapsed into the warmth of his house and took stock of the long weekend. It wasn’t just that he was no longer enjoying himself. He was struggling to match the room’s energy. At times he’d catch himself growing frustrated by the audience’s lack of appreciation for the rhythmic sounds and stories he was sharing with them. It was time, he realized, to make a change.

“I don’t want to be on three different continents in three days,” Seikaly says. “It was taking a toll—I don’t need that. It was time to go back to doing what I had originally set out to do, which is share my music with the people who love it.”

Seikaly decided he’d limit his public gigs to around five a year. He still has the radio show, and there are still the private concerts, reserved solely for those exceedingly familiar with him and his music, which he loves.

But there was also more to his decision to slow down. It just takes a few follow-up questions to pry it out.

“I was feeling guilty,” Seikaly adds, finally. “If I was single and didn’t have a family to take care of, I’d probably be on the road all the time. But I have a daughter and a wife and I was missing time with them.”

Then comes the kicker.

“I’m 1,000 percent happier than I was before.”

Yaron Weitzman is a Senior Writer for SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @YaronWeitzman.

Photos: Courtesy of Rony Seikaly, Suzy Allman/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images, Tim de Frisco/Allsport