Representation matters. That holds true for everyone, but especially so for the misrepresented.

Call it a sense of duty to champion his people’s story, history and identity. Call it a lean toward making the mundane mystical or nostalgia fantastical.

Just make sure to call Tyler Deauvea (@tylerdeauvea) an artist who is a burgeoning incubator of his time, earnestly burdened with the clarity of significance.

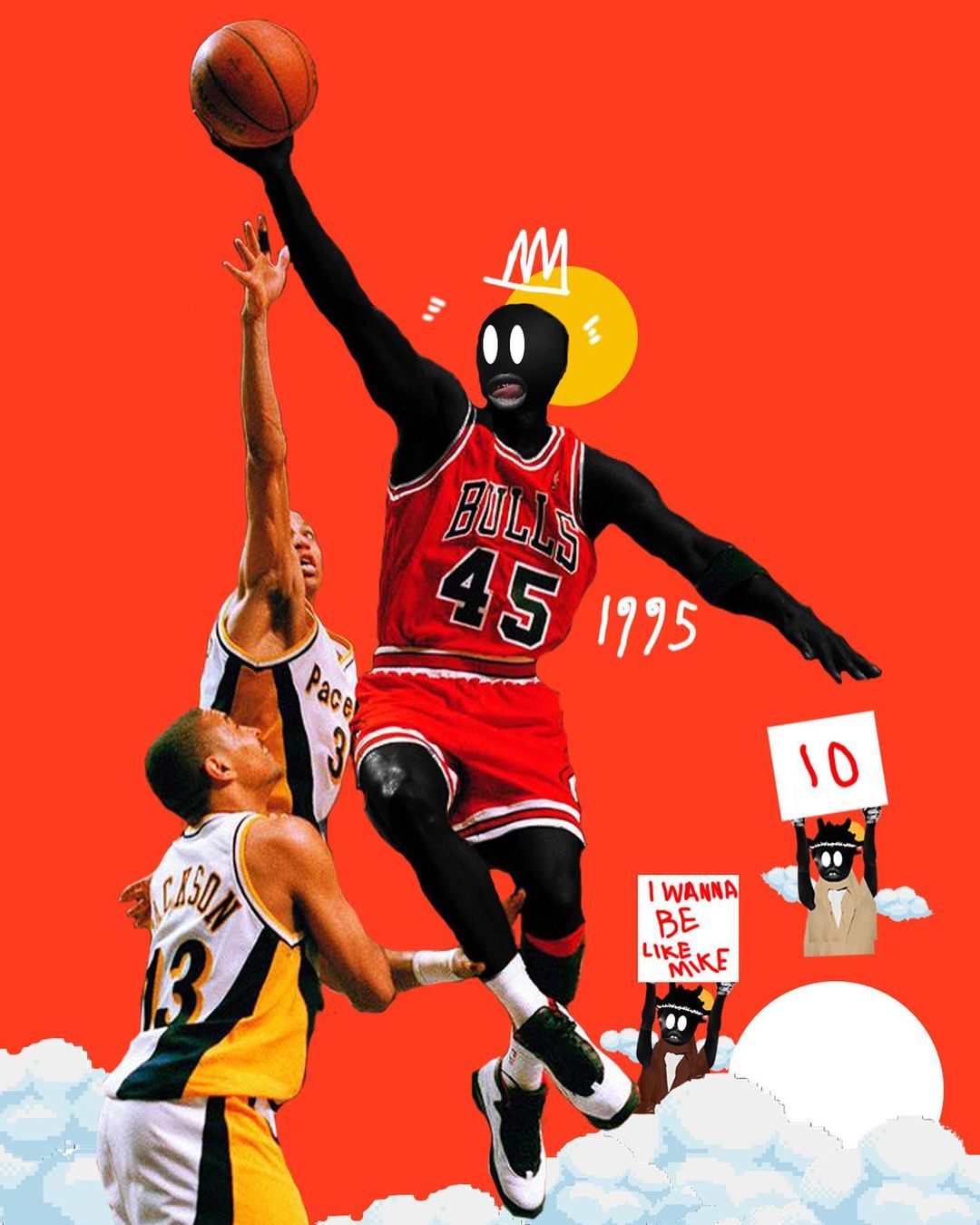

The Houston native’s reverential look at basketball, “For the Luv of the Game,” was sparked by the tragic death of Kobe Bryant, and the indelible imprint the future Hall of Fame guard left on his life.

“I really only make work that I feel,” says Deauvea, who started out in photography and film before opting for collages and other multimedia. “I’ve always loved basketball and I’ve always had in mind that I would do a basketball series, but I really didn’t know in what way I would do it and how I would do it. Then Kobe Bryant died. I was a huge fan of Kobe Bryant. I still am.”

The Black Mamba’s passing led the diehard Los Angeles Lakers fan down several YouTube rabbit holes, where he discovered a treasure trove of his favorite player’s classic NBA games, buzzer-beaters, dunks and interviews.

“I made my first piece because he passed and I was really affected by it just as a fan,” Deauvea says. “I had realized just how much of an impact he had in my life. I realized that he was a hero to me, and I took a lot of what he said, and I use it in my everyday life, subconsciously and consciously. So that’s how it started off.”

Then it was on to Michael Jordan’s Emmy-winning documentary, The Last Dance, and a litany of memorable All-Star games. Basketball fans were all in the throes of the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic and desperately missing the game during the hiatus, so Deauvea started basking in the nostalgia, prompting him to honor the generation of players that inspired him to chase greatness.

“I just wanted to really honor those men who were on my television screen when I was a kid,” Deauvea says. “I want to celebrate them because these are my childhood heroes and they could pass one day. My favorite player passed, so we should honor these men for how they inspired us. Anyone that’s publicly doing well in their craft should inspire you, and for me that’s my big takeaway, but especially basketball because I love it so much.”

The 30-year-old social commentator’s series features pieces on Tracy McGrady, Shaquille O’Neal, Steve Francis, Allen Iverson, Hakeem Olajuwon, Jordan and of course, Bryant, whose “Mamba Mentality” lives on in everything Deauvea creates.

“There’s always people better than you,” Deauvea says. “There’s always people hungrier than you, at times may be more dedicated than you, so you always got to be in the gym, like constantly. There’s no reason to like rest on your laurels, because once your moment is done and you celebrate it, it’s over with. Now you got to get back to work. To celebrate more, you got to get back to work. That’s what the Mamba Mentality is, dedicating yourself to the craft and not being swayed by anything outside of you.

“That’s the same teaching of Taoism and Bruce Lee spoke on that, so it’s definitely a lot of Eastern philosophy behind the Mamba Mentality. I was already studying it before in different aspects, but once Kobe was doing interviews and explaining what it was, I was like, This is so much of what I already like to do. The Mamba Mentality is being a student to whatever you’re trying to do, so I definitely buy into it.”

Edgar Degas was onto something when he said, “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.”

Deauvea’s work, aptly dubbed AFROPOP, takes Degas’ principle to the next level, switching the culture code of negative African-American imagery from its Jim Crow era origins on its head, making the indefensible something entirely new and worth appreciating.

“For me, when I create my characters, I make them that way so that every Black person can identify that this is a Black person,” Deauvea says. “Every Black person can put themselves in those shoes. There’s a book that I read by Dr. Francis Cress Welsing called, [The Isis Papers:] The Keys to the Colors, and it was a whole book about how white supremacy used the color black against Black people and made it a negative thing. So, for me, I’m not going to let you make me feel bad about my black features. When I decided to create characters, I made him as symbolic of a Black person as possible, there’s no way to cut across it.”

Embedded in his work is the idea that everyone can identify with his images of a Black person, not just in normal environments and normal situations, but in a wondrously weird and exaggerated world like those depicted by Asian characters in anime or Takashi Murakami’s Superflat work.

“I just wanted to have Black people in these imaginative spaces,” Deauvea says. “I feel that’s important for kids to see. Even when it came to making the basketball players, I didn’t find the reason to differentiate from what I would do normally because I feel like in basketball, we place ourselves in the feet of these athletes when we watch the game.

“It’s not just the athletes themselves that’s being portrayed, it’s my character in their jersey doing what they would do. It’s anybody who loves basketball and loves that player and remembers that dunk from this game. That’s the concept behind it. My concept is truly a visual inclusion of all Black people. I want Black people to look at Black images, no matter how Black images look, from Black people and be like, ‘Yes, Black.’”

—

Maurice Bobb is a contributor to SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @ReeseReport.

Photo courtesy of David “Odiwams” Wright