It’s the eve of what will be his first MVP season. The one where he will regain his claim to the throne he lost last year. He knows this, but will never say anything. He’s been trained not to. Understand, he has a degree in psychology. That’s the foundation. He’s smart. He’s cunning. He’s cold as the ice he sits on.

It’s been said that no one has gotten inside the head of Tim Duncan. That he’s been impossible to break down, that no one has gotten him to open up. In that, he’s the closest thing to Michael Jordan and Bill Clinton we’ve seen. Slick like arbitration, crafty like a Beastie Boy classic, coy like the end of a House of Games. Read his bio and you’ll discover more. But still you will come up empty. He planned it all that way. Inside his handshake is a welcome mat followed by a “Do Not Enter” sign. It’s all the brilliant, cognitive contradiction of a 24-year-old man who was born to be different from the norm and superior to the average. He’s become both.

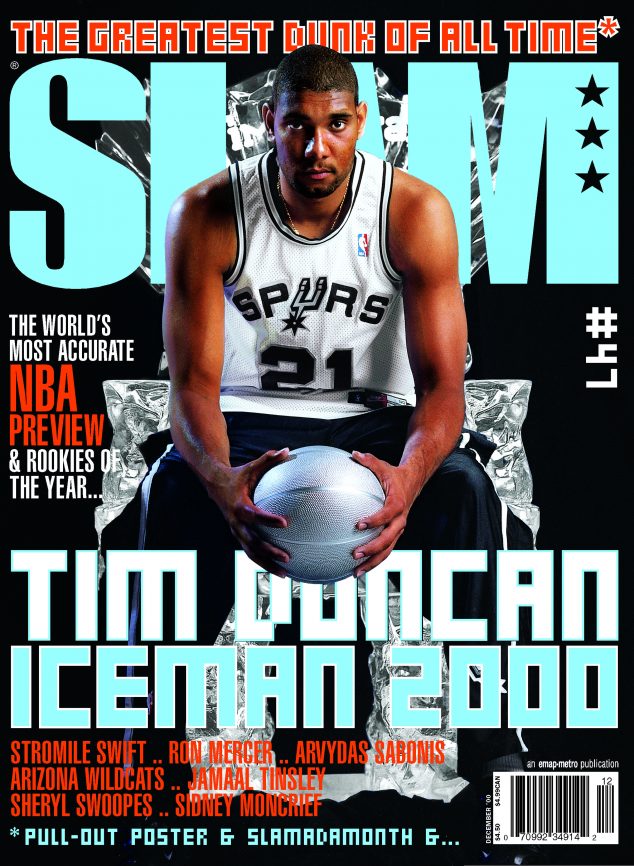

But to get inside of Tim Duncan, we set him up. Played the same mind trick on him that he plays on everyone else. “Tell Tim we want to recreate the Iceman poster from back in the day,” we pitched to Tom James, the Spurs media cat who was in on the fix. “Yeah, yeah, tell him it was Gervin’s idea.” The lie worked. It was only a matter of whether we could out-master the master. Get the interview no one else has been able to get. And though Tim bit, his game recognized our game in the end. The first thing they teach you in Psychology 101 is “never put yourself in a position of weakness, because the payback can be a bitch.” For this story though– just this one story– the real Tim Duncan got got.

“Was I scared? Yes.” This is Tim Duncan’s voice. It’s not cracking, it’s not an extremely high pitch, but it is with emphasis. He has not balled in two months, he’s had major surgery on his left knee, he’s missed the Olympics. There is uncertainty that comes with fear, especially if it affects your mental as well as your physical. The injury, the surgery, the rehab. The fear existed in Duncan through all three. But it was in his mind where the fear manifested most. This was not a faux, Wes Craven-induced dream. Duncan’s being scared is for real. To the point where he thought, well…

“I wondered if I’d be able to play again. My fear was that this was the longest period of time I’d ever gone without touching a basketball. And I really didn’t know when I was going to be able to.”

“And that scared you?”

The calmness comes back to his voice, “Yes it did.”

But to look into his eyes and in his face, you could never tell. He’d never let you there. Not to focus so much on the injury, but the impact of it cannot be denied. Beyond a slight bit of confidence lost and skepticism gained. His status/title/rep as the “best ballplayer in the league” got passed around last season to all who came crawlin’ up his mountain. One week it was Vince, the next it was AI, then Kobe, then KG, then anyone else who wanted it. “That didn’t bother me a bit,” he says of his lost pound-for-pound crown. “I’ve heard everything. I think, no doubt, last year Shaq was the best player. I also think Vince is an amazing player. And you’ve got to give some props to Allen [Iverson]. And KG, that kid’s incredible. He’s as good as anybody but he doesn’t get as much [credit] as he should get because his team right now doesn’t do as well as it’s going to… ” Tim pauses and thinks about exactly what he’s saying. The analytic in him ekes out. “Well, hopefully it will stay that way as long as I’m around,” he continues with a Western-Conference-rivalry-with-the-Timberwolves laugh.

“To me, there are a lot of players who can be given that title at one point or another during the year, but the one who’s going to carry [the “best” title] through for that year is the one who takes his team to the top,” he adds. “I was given that title the season we won [’98-99]. Shaq got it last season. Was it due, did I deserve it when I supposedly had it? Yeah, I think so, a little bit. But I can’t really worry about it, because there’s going to be arguments about every year. You know what they say, ‘You’re only as good as your last game.’ And that is so true.”

So true to the point that one “unnamed” (OK, Lindy’s) pre-season basketball magazine had Duncan ranked No. 3 in the League—not among players, among forwards! Rated behind KG and the person who really should have replaced Duncan on the Sydney Squad (no disrespect Antonio McDyess), Chris Webber. When told of this, Duncan laughs in hesitated breath. It’s as if the split personality that he doesn’t have separates: part of him agrees, part of him doesn’t.

But after about 20 seconds of thought, the conclusion is made. The left hemisphere overrides the right. “Chris had a great year, he’s an incredible player. He had some great games against us, that’s for sure. And he did a helluvalot for that team. So who am I to argue? I won’t dispute [the ranking] at all.” Then the right hemisphere emerges. “But when we go head-to-head, it’s a different story. He’s gotta play, I gotta play. So it doesn’t matter what [the magazine] says.”

Still, nothing sweats him. Even when he’s being pushed for answers of anguish and being personally challenged. Doesn’t he understand we’re trying to piss him off, get him rattled? He’s fucking up the plan. Damn you, Duncan.

If you follow him over time (especially during the season), what you find is illuminating. Tim Duncan is not a brooder. He’s not boring, stiff, or flat. He isn’t slow, either; he moves at what is called “island speed,” an “irie pace” that is indicative of his St. Croix, Virgin Island, roots.

“People think he’s all shy, buy he’s sly.” Scott Duncan is Tim’s half-brother. Maybe more than anyone, he knows the Tim Duncan we are in Leonard Nimoy of. “Many people don’t get him, they think he’s boring, but he’s really opposite. He has this cool intensity, and the deepest running sense of humor. He catches everything. Nothing gets by him.”

He says the family is proud of Tim and that he’s on the path he set for himself as a child. “[Tim] knows his destiny and has been knowing of it for a very long time. He’s always been true to his inner self and totally trusts his instincts and feelings, which is why he is so cool. That’s why giving him the name ‘Ice’ is so perfect,” he continues. “It fits him. In his personality, it’s like he always keeps the ice flowing.”

If you get to know him, he’ll surprise you with his quick wit and sarcastic sense of humor. He’ll say the illest things, but only under his breath so no one except the person he’s talking to can hear. He’s a computer-head, specifically on the galaxy game StarCraft, where he attacks the program as if it were Rasheed Wallace. On laptops, he, David Robinson, Malik Rose, and Sean Elliot will battle for hours, especially when on the road. He’s a film buff and critic, the black Roger Ebert. He can also spit some Nas or DMX lyrics if anyone claims he “ain’t ghetto enough.”

He’s a playground legend by default (“Growing up where I did,” he says, “all we had was outside courts.”). He’s an icon of Ian-Thorpe-in-Australia proportions in his hometown, to the point that he can’t go back without getting mobbed with the deepness of Havoc and Prodigy. Even he admits, “I don’t get back [home] as much as I should.” His clique consists of his two sisters, Tricia and Cheryl, Scott, and his long-time girlfriend Amy.

He plays the crib a lot, meaning: He likes to spend time at home. Not that he’s shy, but he doesn’t invite distractions in his life. The brotha who grew up in the neighborhood who never came out of the house to floss, but wound up with the flyest whip because he saved his allowance by not hitting all of the parties? That’s Tim. The rumor (one explains a lot about Duncan) is that he’s so laid-back that during the weekend of his first All-Star Game (in ’98 in New York), he didn’t do anything. Never went to one of Puffy’s 300 parties. Instead, he and Amy room-serviced. Understand that everyone doesn’t need the spotlight to shine. Some gleam on their own.

Most important, though, in this search for the inner Tim Duncan, is the discovery that no one in the League will say anything bad about him. There are no enemies who pray and pray for his downfall, even though he may slay them and lay down law on court. Around the NBA, Duncan and Vince Carter seem to receive the most universal and unconditional love. And in a League filled with literal “player hating,” that the truth speaks more than volumes about Duncan. It soundbombs.

The phone rings once in his spacious San Antonio crib before he picks it up. It’s one day after he had eye surgery to help him “never lose sight of the rim.” He laughs at this, as he does at most everything. He’s just cool like that. After a few “wassup young fella,” it’s the business. “Tim Duncan? Let’s talk about Tim Duncan…”

George Gervin is the second installment of the Iceman moniker originally given to Jerry Butler, who used to sing with Curtis Mayfield. But Gervin took it to a level beyond resurrection—until now. When he blessed neighborhood sports store windows in the ‘80s with that unforgettable image for Nike, the understatement could be made that he “redefined what cool is supposed to look like forever.” Like Clyde Frazier before him, Gervin was on some other shit that no other athlete could pull off. No one had the character, no one exemplified the persona, no one else had the game. When told of the concept for this cover, Gervin had one thing to say: “Am I mad? Hell naw! I’d be mad if you called somebody else that. That’s a compliment to me.”

It’s not just the “iceness” that connects these two, but something deeper. It’s what occurs when they touch a basketball and bless the floor. It goes beyond the eerie coincidence of both playing in Spurs uniforms. As Gervin attests, “The things he can do at his size remind me of a guy named “Ice.”

They share the cashmere-soft, Victoria’s Secret-smooth jumpers from angles Willie Mosconi would love; the footwork reminiscent of Bill Robinson and Maurice Hines, unmatched by players their size; the effortlessness with which they perform and their ability to become instantly undefendable in (big) game situations, never “playing outside of themselves;” the finger roll.

The Original sees it in Duncan, probably more than he does in his own son, Gee. “There are players you pay to see. Tim Duncan is a player I’ll stand in line and pay to see,” he says. But in conversation with Gervin, it’s clear the love he holds for Duncan is far more important than what Tim has done on the court—even more important than the ring Tim brought the city last year and the one he’s planning to bring back this season (Duncan: “Don’t forget we are the same team swept the Lakers and Portland in the playoffs two years ago. We just need to be healthy and consistent, not necessarily better.”). It’s about the person Tim Duncan is, the one we are trying to expose in this story. Gervin gives us an answer.

“Whenever a guy of his stature still asks me for an autograph, that says something to me. I love that. See, don’t nobody want to be forgotten. I did my thing, you know. But every time I see him, he makes me feel as if I meant something. Meant something to the game, meant something to him personally. And he’s done that without even saying it to me. That’s class. You want to know what type of cat Tim Duncan is?” Another signature laugh comes out. “The young fella is a beautiful person.”

The first true encounter of “the individual that is Tim Duncan” came at a Nike Camp about four years ago when he was a summer counselor following junior year at Wake Forest. Somehow the rumor had gotten around that Tim’s nickname was “Cookie Monster” (A joke started by another counselor named Todd Harris). Tim hated the name. For the entire week, he got grilled with the name, never even knowing why he was being called that. “I hated that shit,” Tim would say. But did he say anything about it then? No. He never gave it power. His shell would not be cracked, not by that. He even read it in print before he entered his senior year, but still he gave SLAM love.

But it was after hours at that Nike camp where “Tim Duncan the ballplayer” emerged to our eyes. For two to three hours after the “invitees” night sessions were over, Tim got his freak on. He was often teamed with then-Eastern Michigan 5-6 point guard Earl Boykins. For an entire week, every night against other college All-Americans including Vince Carter and Miles Simon, Duncan and Boykins played something that looked a lot like 2-on-5 basketball. And they were winning. No one had any idea that Duncan could play transition basketball like that. As fast as Boykins was, there were times when Tim was beating him down the court, waiting for the oop. He was freaking smaller players with spin moves that gave him the baseline so open Monique from The Parkers could have slid right on through. He wasn’t just the “post-up” player we had labeled him; in all honesty he wasn’t even a center. But he wasn’t going to say anything. He let the secret about his game get out all by itself. And here’s the funny thing: by the end of that camp, no one was calling him “Cookie Monster” anymore.

This was the first lesson of understanding the psyche of Tim Duncan and how it works against others to his advantage. But still there are depths that remain untapped by anyone. The game continues. Tim seems to be getting mad comfortable with the tape recorder rolling. Our plan is working.

“What makes you laugh?”

He laughs. “Stupid humor. Jim Carrey movies, the Three Stooges, Friday, things like that. Who makes me laugh? Man, Antonio [Daniels] and Malik [Rose], those guys make me laugh more than anyone because they are silly, stupid for no reason.”

“Just like you, right?”

“Exactly,” he says.

“What’s the worst thing you ever did as a kid? We know you quiet and humble, but you had to do something scandalous coming up.”

He laughs big. “Uh, shit, I can’t think of anything big, but I got in trouble a lot…”

And just when he gets comfy, we change the pitch up. Hit him like we’re interested in basketball.

“Are you ready to do this solo?”

“What do you mean?” he says.

“Are you ready for the day that DR [David Robinson] stops playing?”

“Oooo…good question. No,” he says. “David is a big part of the reason I didn’t go anywhere.”

“You said that in the press conference, but tell us the real reason.”

“That is it,” he confirms. “And I love the area. I love playing with David and I think we have a chance to win another championship here. Plus, I like playing for Pops [S.A. head coach Greg Popovich]. I love the way he motivates the team and the direction we’re going.”

“Then why’d you only sign a three-year deal instead of signing for the long money?”

“Always keep your options open,” he says, being totally candid. “I’m not sure that I’ll even want to be in San Antonio in four years. DR may not be here, Avery may not be here. I’m protected, I’ve got four years of really good money. But after that time, I gotta be able to do what I want to do.”

“Did it piss you off when you heard the Spurs were trying to trade Avery Johnson last season?”

“You know what, the one thing I learned from day one in this game is that it’s a business, it’s not about friends,” he continues. “Ever since the day I got here, all of my best friends got traded or they weren’t re-signed. Chuck Person, Monty Williams, Cory Alexander, none of those names are still here. And those were my best friends in the world. But it doesn’t take away from the fun of the game. And I’ve been able to separate that. When we’re on the floor. Out there, basketball is basketball.”

“What scares you?”

He stands up. “Heights. Yeah, heights and sharks.”

“What about on the basketball court?”

“Not being able to play anymore,” he says as we relive the opening of our conversation. “Being injured again, that scares me. That scares the hell out of me.”

“Nice.” He says this while looking at his name iced in the chair he just finished sitting in. Then it hit him, the whole scam. He figured it out without expressing that he knew. If you play poker, you can see it in someone’s expression, there’s a small glisten in the eyes. But maybe it’s just a sparkle of what Tim sees in himself. No, he know. He figures he’s just been played. He figures that SLAM did all of this to “get me to open up, say something that I normally won’t say in an interview—they were trying to get to know me.” He mentally acknowledged that we’d done a good job. He appreciated the skills. Like we said, game recognizes game. But if you’re a psychologist with a superlative b-ball game, you don’t settle for that. Instead, you get even.

“Who do you see in you?” Tim asks, flipping the interview, setting up the set up. The question is posed after a discussion about who he identifies with. “There’s always one person,” I say. “That one person we see ourselves in.” It’s fantasy versus reality. “I see Sidney Poitier in you,” is what Tim Duncan hears. He relates. “I always saw him in my father,” is his response. It’s the epitome of that dignity thing that white Americans see in Cary Grant that we both see. I see it in Tim, Tim sees it in his father. Many mistake Tim’s quiet for something that it is necessarily not. It’s like “whatever” when his name is mentioned. “Man, people think you’re boring but you’re far from it.”

“I’m fun to myself,” he says.

The conclusion: Yes, Tim Duncan is quiet, but not uninteresting. Too few see that.

I answer Duncan’s question by saying, “Spike Lee.” Tim’s head shakes in agreement, he can see that too. “What about you?” I ask him. “What other individual do you see in you? Who does Tim Duncan see?” It’s the deepest and most personal question I asked him on this day. It’s the one answer that will complete the story, the answer none outside of the people around him has ever gotten. Instead, for the first time, except for when the photos are being shot, he’s silent. Five minutes pass. Then 10. He’s still quiet, says he’s “thinking.” I see that famous smirk of his. He just played us back. By the time you read this story, Tim Duncan will still have not given us an answer. He purposely did this, That was ice cold. Payback is a bitch, ain’t it?

—

Portrait by Atiba Jefferson