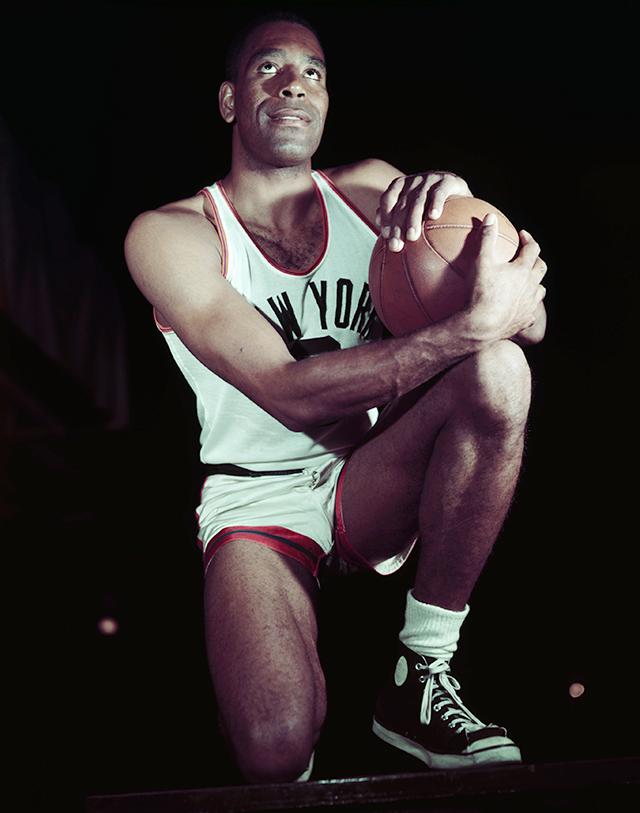

Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton didn’t get his due.

In the late 1940s, the all-white Lakers had a widespread reputation as the nation’s best basketball team. George Mikan, a 6-11 big man as dominant in his time as Anthony Davis is in ours, was on the cusp of leading Minneapolis to five of six titles in the NBA and its predecessor league. Yet the 6-7 Clifton almost shut Mikan down while matching him on the boards when the two battled one-on-one in the pro basketball event of the decade.

Clifton was a headliner for the Harlem Globetrotters, which then attracted the nation’s best black players—not the NBA. The extremely talented Globetrotters were good, so good that on a single night in 1949 against a short-handed Lakers team, they rolled out to a lead so large that as the game wound down they started to clown around. Stuffing balls down jerseys and all that jazz. The win was filmed—still a rarity at the time—and shown to millions of Americans who soon realized the best black basketball players were just as good as the whites who would make up the entire NBA in its inaugural game in 1946.

Yet as accomplished as Clifton was, he wasn’t compensated at anything near the level of the League’s best white players. While among the highest-paid black basketball players of the time, his earnings paled in comparison to even the collegiate stars that the Globetrotters took on.

“We played an all-star game [in 1949] against a team Bob Cousy was on,” Clifton told the Chicago Sun-Times in 1986. “After the game, Cousy, who got to be a pretty good friend, asked what [owner] Abe Saperstein paid us. He showed me his check for $3,000. I was ashamed to show him mine. It was for $500.”

By 1950, New York Knicks president Ned Irish was ready to give Sweetwater a chance. He purchased his contract from the Globetrotters in May 1950 for $10,000, Clifton later recalled. Clifton became the first black player to sign an NBA contract. (He was technically the second to sign an NBA contract, but Harold Hunter, who did so beforehand, never played in an NBA game.) He followed Earl Lloyd as the second African-American to play in the League.

Sweets, as he was best known, had immediate impact. He helped lead the Knicks to three straight NBA Finals appearances while practically averaging a double-double. His long-time affinity for any kind of sweetened drink led to him becoming an ad pitchman for Coca-Cola, a nascent sign of the vast cross-cultural influence black NBA players would accrue in later decades, according to Martin Guigui, a director who has researched Clifton’s life for nearly two decades.

By all accounts, Sweetwater was a soft-spoken, hard working man whose professional conduct helped open the doors of opportunity for great black players like Elgin Baylor and Bill Russell who would follow him. “He was a pioneer for me and a lot of other African-Americans,” Oscar Robertson said in a tribute at the 2014 Naismith Hall of Fame enshrinement ceremony.

While Clifton, who passed away in 1990, was comfortable with his role as a trailblazer, he wished he could have done more. He regretted not having a shot at more stardom in his own right. “I feel like I was the best player in the League in my day,” he told the Sun-Times. But “I was only allowed to shoot about six or seven times a game…Only when it was late in a tight game would they turn to me for scoring.”

The coaches didn’t design offensive plays for him despite the fact he occasionally chipped in more than 30 points a game. “All I was really allowed to do was to rebound, hand the ball over to my teammates and guard the toughest players on the other teams.”

The rare opportunities in which he showed his stuff left jaws dropped. “He could cross the court in five strides,” and had what today would be a three-point shot, Guigui says. Sweets also handled the rock better than most other players at his position. Guigui says he has footage of him bounding downcourt, throwing the ball off the backboard and slamming it down, à la the Tracy McGrady self alley-oops of the early 2000s. Such displays were generally not welcome by coaches and other players, as Clifton recounted to the Sun-Times: “I realized that, being the first black, I couldn’t do anything people’d notice. So I had to play their type of game—straight, nothing fancy. No back-hand passes. It kept me from doing things people might enjoy.”

Restraints notwithstanding, in 16 total years in the NBA, the Globetrotters and touring team spinoffs, Clifton secured a legacy as a critical figure in the evolution of basketball from brutal, floor-bound East Coast roots to the high-flying global phenomenon it is now. “More so than being one of the first African-Americans, along with Chuck Cooper and Earl Lloyd, he really shifted the game,” Guigui says.

Clifton developed his innovative style alongside basketball geniuses like Marques Haynes and Goose Tatum, who were his Globetrotter teammates. That franchise’s beginnings trace not in Harlem, but to the South Side neighborhood in Chicago where he grew up.

***

Since the age of 6, when his family moved from Arkansas, Clifton saw some of the finest basketball players of the Depression Era play in and around the South Side Boys Club.

Al “Runt” Pullins, a prodigiously gifted 5-8 scorer with the original Globetrotters, “was about the greatest I had ever seen. That’s who I copied most of my style from,” Clifton said on a 1985 episode of Once a Star.

Clifton took to heart what he watched the young men do, and became a star at DuSable High School and Xavier University in Louisiana. Not just in basketball, either. Sweets was considered an even better baseball player, so good that in the late 1940s, he was on the cusp of the majors after leading a minor league in home runs, total bases and batting about .350, according to Chicago sportswriter Sam Smith. He was even more intriguing to the likes of Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck after success in a higher minor league, batting over .300 and again leading in homers and RBIs.

Afraid he’d lose one of his star players, Globetrotters owner Abe Saperstein quickly arranged for Sweets to play on a world tour, Smith wrote in the 2014 Hall of Fame enshrinement guide.

Clifton’s life changed forever in 1950, a year holding the same importance in basketball annals as 1947 when Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s major league color barrier. Yet for decades, Hollywood has largely ignored this monumental turning point.

That changes soon.

Sweetwater, the first major motion picture focusing on the NBA’s first years—is now in production and is scheduled to come out next year, according to director Martin Guigui and IMDb.com. The plot centers on two eventful stints in 1950—the NBA Draft and signing of Clifton, as well as the week around Halloween when Lloyd, Cooper and Clifton “were sort of pitted against each other in a race to see who would be the first black NBA player,” Guigui says.

The roughly $20-million film will star the 6-3 Wood Harris, who’s perhaps best known as Avon Barksdale from The Wire and made his film debut in the 1994 drama Above the Rim with Tupac Shakur. The ensemble also includes Nathan Lane (Saperstein), James Caan (Ned Irish) and Ludacris (musician Louis Jordan).

Sweetwater will draw inevitable comparisons to the 2013 Jackie Robinson biopic 42. Clifton, like Robinson, had to deal with persistent, vile streams of racism that could make even Donald Sterling blush. Yet both pioneers overcame the adversity. Robinson played in six All-Star games while Clifton played in the NBA All-Star Game in 1957 at the age of 34—to this day that remains the oldest age of a first-time All-Star.

“Sweetwater’s fight for acceptance in the basketball world is an example of the struggle faced by so many African-Americans at that time,” NBA Commissioner Adam Silver says. “As one of the NBA’s first African-American stars, he not only laid the groundwork for the League to become the diverse institution it is today but also help drive social progress across the country.”

But Clifton and Robinson got to this end in different ways. Robinson was famously stoic in the face of opponents’ taunts, especially in public and during games. Clifton usually was, too. Except when too much was too much.

Once, during an exhibition game against Boston, Sweets threw a dazzling pass past Celtic Bob Harrison. Harrison didn’t appreciate the style points at all, Clifton told the Sun-Times in 1986. “He said, ‘No nigger do that to me,’” recalled Clifton. “It was a one-lick fight. I was lucky enough to knock him out.”

Clifton was not only a fighter, but a lover who enjoyed the New York nightlife. Sweetwater will depict his affair with a high-society orchestra vocalist who aspired to sing the blues. “She’s a white woman who wants to live in a black man’s world and Sweetwater was a black man wanting to live in what was then a white man’s world,” Guigui says.

Clifton played in the NBA for eight seasons with the Knicks and then the Pistons. He spent much of the last 30 years of his life driving a yellow cab around Chicago, sometimes picking up the NBA stars for whom he’d help pave the road to millions. More than a few times, an older passenger would peer at him for a minute, seeing something familiar in his pronounced chin and massive hands.

They would ask, “Have you got a brother or something like that playing ball?’” Sweetwater told Once a Star documentarians while driving his taxi. Clifton would then tell the passenger who he was. They’d respond “No, you’re not Sweetwater.”

“I’ll say, Well, I guess I’m not then, if you say so.”

Sweetwater had reasons to be bitter but was not.

After decades of travel, he relished being back home, able to care for his ailing mother, his three children and later their children. Sometimes, he’d drive by Carter Playground, lift his overweight frame from the black seat cushion and play three-on-three with neighborhood kids.

Money was tight—he never made more than $12,500 in a year of pro ball and he didn’t receive the pension that NBA players who retired after 1964 would get—but he had family, he had a community and he had a craft. “I’m the best cab driver in Chicago and if I’m not, I’m at least the fourth or fifth best,” he told the Sun-Times in 1988, two years before he died from a heart attack while behind the wheel.

It wasn’t a life to which today’s NBA stars aspire, but it still held vast riches. Perhaps nothing shows this better than the end of the Once a Star episode. Sweetwater sits on his wooden front porch, beaming at his two young grandchildren as he holds them on his knees. Soon, his daughter, his mother and a small army of neighborhood children join them.

Clifton never got what he deserved while he was alive.

Yet he had what he wanted.

—

Photos via AP