I963, two Boston dynasties met up in Washington, DC, when President John F. Kennedy hosted the NBA Champion Celtics at the White House. With names such as Russell, Cousy and Auerbach in the room, it was an underrated forward who stole the moment.

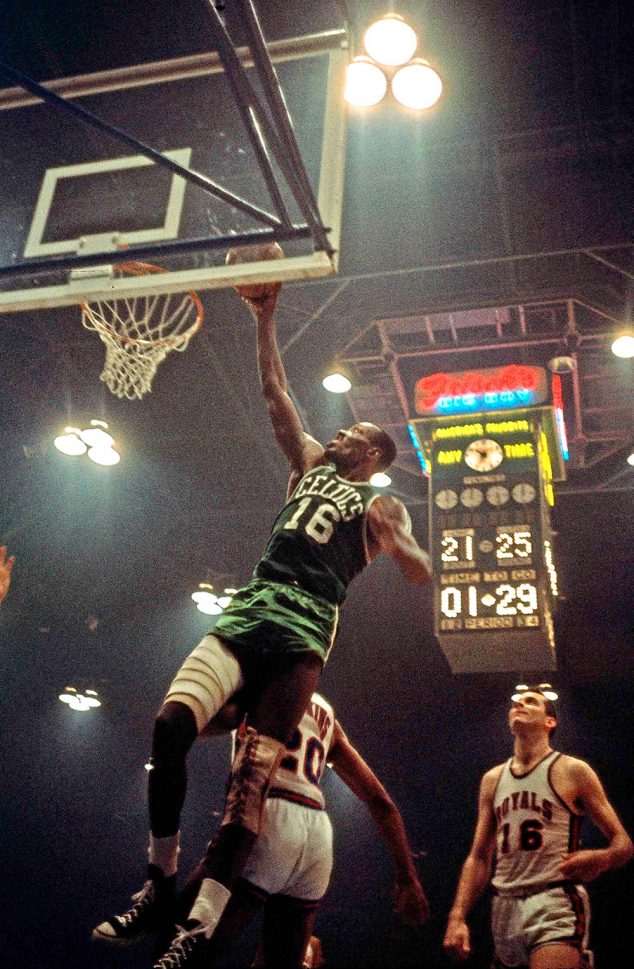

Satch Sanders—born Thomas but known by his nickname—wasn’t the most publicized of the 1960s Celtics, but he was an indispensable part of their dominance. Sanders exploded onto the NBA scene as a rookie in Game 4 of the 1961 Finals when he scored a season-high 22 points and provided pivotal defense and rebounding to beat Boston’s archrival, St. Louis Hawks.

Between 1960 and 1973, Sanders played 916 games and averaged 9.6 points and 6.3 rebounds. He was the League’s Iron Man, playing in a then-record 450 straight games. Before there was an All-Defensive team, Sanders was a stopper who defended future HOFers Dolph Schayes, Bob Pettit, Oscar Robertson, Elgin Baylor and Chet Walker. His eight NBA Championships as a player are tied for third most all-time.

In today’s game, Sanders would be comparable to Andre Iguodala—that is, if Iguodala regularly defended 7-foot centers. Tall Tales by Terry Pluto is an authoritative oral history of the Russell-Wilt years—just a quick scan of the book’s passages on the Celtics dynasty make it clear that, among his peers, Sanders was considered the premier defensive forward in the league: a wiry 6-6, 210-pound defensive menace.

“To forwards, Satch was a nightmare. He covered you like a blanket. I never faced a forward who played the defense Satch did,” said Jack Twyman.

The premier scorer at the time, Elgin Baylor, told Pluto, “When I think of the Boston defense, I think of Satch Sanders. He was about my size (6-6). He was aggressive but not dirty, and he lived to play defense. He was totally unselfish and the toughest player I ever went against.”

Also in Tall Tales, Sanders described his breakthrough this way: “When I came to the Celtics [Jim] Loscutoff was coming off a back injury and there was a chance for me to play immediately if I could show I played very stern defense. I was there to guard people, to pass to my teammates and do only a minimum of shooting. If I stepped out of that role, I’d hear abuse from Red the likes of which I never heard before.…At times, sacrificing my offense was frustrating. But I also knew that my teammates appreciated me, and I took tremendous satisfaction in the winning.”

Sanders was rarely the leading scorer but he was always the consummate teammate—the consummate Celtic. That day in the White House, though, Satch wouldn’t be stopped from making an individual move—a smooth exit from the leader of the free world.

“We spent over 35 minutes with the President. Usually you might just get a handshake and a picture and you’re gone. But because he was a Massachusetts guy and a Celtics fan, we had a lot of laughs—he had a great sense of humor,” said Sanders. “Kennedy was a fan and a nice man so when it came time to say goodbye it was nothing to say, ‘Hey, take it easy, baby.’”

Satch wasn’t just on the front line of the Celtics—he was on the front lines of change taking place in the US. In 1961, Sanders and his black teammates, including Bill Russell, boycotted an exhibition game in Lexington, KY, after he and Sam Jones were denied service in a coffee shop. On December 26, 1964, Sanders was among the first all-black lineup to start an NBA game.

After he retired, Sanders continued to contribute to the game. In 1973 he became the first African-American head coach in any Ivy League sport when he took over Harvard basketball. In 1987—when John Lucas’ rehab center could field as good a starting five as some NBA teams—Sanders inaugurated the player programs department and developed the rookie transition program, the first of its kind that was later adopted by each of the other major sports leagues. In 2011, the Hall of Fame inducted Sanders as a contributor, recognizing his overall impact on the game.

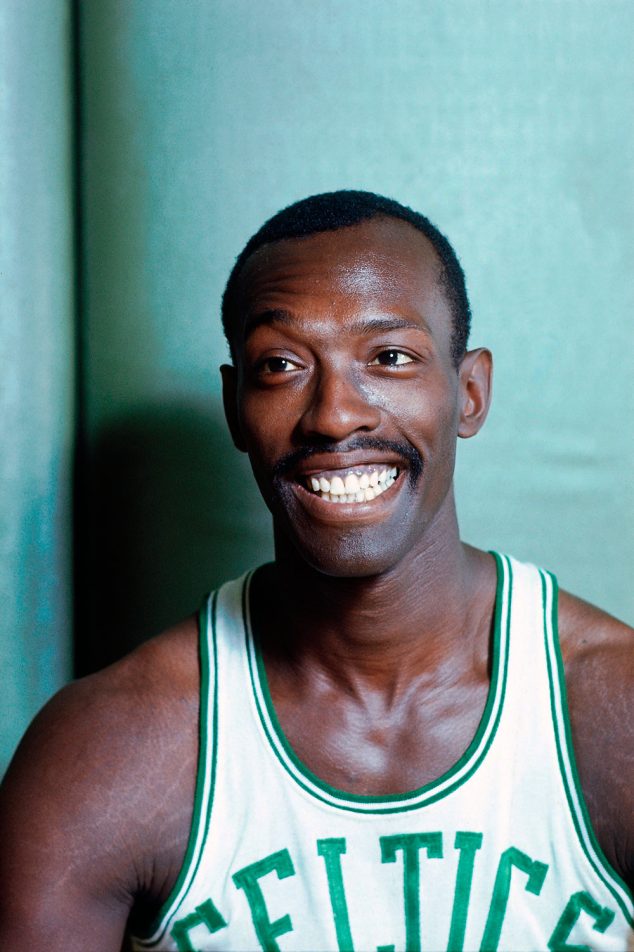

In addition to his many accomplishments, Sanders is known around Boston for being an engaging, perceptive conversationalist—his book of short stories, Satch’s Commuter Moments, reveals Sanders’ wry perceptions of the human condition.

Given what an amazing career this great man has had, we were thrilled to sit with the 77-year-old in downtown Boston recently and discuss it.

SLAM: You were the top defensive forward in the League. Who was your toughest match-up?

Satch Sanders: Elgin Baylor was the best in the world. There were times I could hold him scoreless for two minutes or two plays. But if he was going to play 40 minutes I can enjoy those two minutes but rest assured I was getting my ass kicked the rest of the time. He was the best I ever played against. I think he was the best all-around player I ever saw—bar none.

SLAM: In your Hall of Fame speech, you mentioned your early mentors were on the Harlem Rens teams of the 1930s. How did you meet those guys, like William “Pop” Gates?

SS: Many of the former Renaissance players lived in Harlem. Pop Gates was one but there were five or six guys—Charlie Isles, numerous others. When they saw kids out there playing, they would call you over and if you were open to criticism they would help you and if you were not, they would tell you what to do with yourself. We all knew who the older guys were and it was great to be out there with them. Some were still playing with us at 40 or 50. They taught me a lot. I learned from guys who could really play.

A lot of people were concerned about young people and how they carried themselves. If they saw you treat people with disrespect in the street, a lady might strike you and then tell your parents why she struck you. Then perhaps there would be another whipping. You were respectful to adults because they were all looking out for you.

SLAM: You played in some Rucker tournaments in the ’50s. Your battles against Cal Ramsey are legendary. Did you know Holcombe Rucker?

SS: Yes, Holcombe was a nice man. He was a park director and his interest was trying to get guys to use basketball to get college educations. Most of the guys did go down south to the black colleges since they could not go to the majority of colleges. By 1952-53, there were only four or five black guys in the NBA by then—including Nat Clifton, Chuck Cooper, Earl Lloyd. At the Rucker, you had guys from the Globetrotters and the Eastern League—all the places where black guys could play. Guys with local reputations—guys who should’ve been in the NBA.

I played at Rucker through the 1960s when I was a professional. To the best of our knowledge, this is where people came to play. Even Oscar Robertson when he visited New York wanted to play at the Rucker. Philadelphia guys would come up. Brooklyn was a rivalry and definitely New Jersey.

There were lots of legends—guys touching the top of the backboard. If the basket is 10 feet, top of the backboard you’re talking about 14 feet, so you tell me, how could anyone get up there? The only guy I saw who might be able to reach those tremendous heights was Wilt Chamberlain, who I played with and against at the Rucker—mostly against. As a 7-3 high-jumper, if anyone could get to the top of the backboard, it would have been Wilt.

SLAM: You even defended Wilt in the NBA.

SS: I played against Wilt when Russell was hurt for three games. My performance was forgettable and he was not tested: he scored 48, 50 and 50-something points. I scored well, too—I scored close to 30 a game by bringing him outside.

SLAM: Did you employ any of Bill Russell’s secrets in defending Wilt?

SS: There weren’t any secrets, just a lot of different approaches and hard work. Front him or force him outside.

SLAM: You’ve had a great impact on playground basketball in Boston, too. As a co-founder of the Boston Neighborhood Basketball League, you helped develop generations of Boston’s inner-city talent, including Shabazz Napier, who is in the NBA now. One of your co-founders was Ken Hudson, the first African-American full time NBA referee.

SS: Well, I won’t talk about his refereeing skills.

SLAM: He was short.

SS: Yes, but I would question his vision, his decision, his judgment as a referee. He was a real good guy though, a great guy, and we got together and were talking about how Boston had some good basketball competition, some good kids. When Boston teams came to play in New York, Boston had always represented themselves well. So when I came to Boston to play for the Celtics I thought, Hey, why can’t we start a league? There was a circle of strong players in Boston.

SLAM: The Celtics of the 1960s are remembered as possibly the greatest team in sports history. But you faced obstacles such as discrimination, jeers and racist attacks on the road and in Boston.

SS: There are always opportunities to check out American racism—when you’re traveling, looking for transportation, food or hotel lodging. It was all part of being black in America—far more than one incident. Situations in Lexington, Indiana, L.A.—this is America. In Kentucky the black players refused to play in the exhibition game for the service situation. That was the times. Martin Luther King Jr and other outstanding people were making changes about how America looked at the relationship between black and white. But if you were trying to go places, rest assured you would run into racism and bigotry.

SLAM: In December 1964, the Celtics made NBA history when they put an all-black starting five on the floor. Was it commented upon?

SS: The first substitute for Tommy Heinsohn was Willie Naulls—it was automatic. When Bob Cousy came out, KC Jones went in; when Bill Sharman came out, Sam Jones went in. These were the natural order of things for our team. So when Heinsohn got hurt, Naulls came in. [Cousy and Sharman had retired the year before.—Ed.] Nothing unusual about that—it just turned out everybody on the starting five was black. History is interesting, a lot of things grow, a lot of yeast comes out of things that happen just naturally.

SLAM: Did you know you were making history?

SS: Now think about what you just said: Did you know you were making history? We knew we had a game to win—Heinsohn was a high scorer but Naulls was, too. We knew we didn’t lose any offensive power, that’s what we knew. History? Things become landmarks based on people looking back and saying that was history. They grow as time passes.

In 1964, Ali won the championship—guys were stepping up, doing things, saying things, trying to get stuff to change. No one was trying to make a historical moment, just even the playing field. That’s what it was all about. Were slaves making history when they were hung or killed? When slaves stood up and said, No, you can’t do this, you can’t take my wife and kids, was that historical? Of course, but if the bright lights and publicity weren’t there it was just another important moment. Who really writes history?

—

Photos via Getty Images