“My earliest memories are going to playgrounds in Queens and realizing that basketball was a real big deal in New York City.”

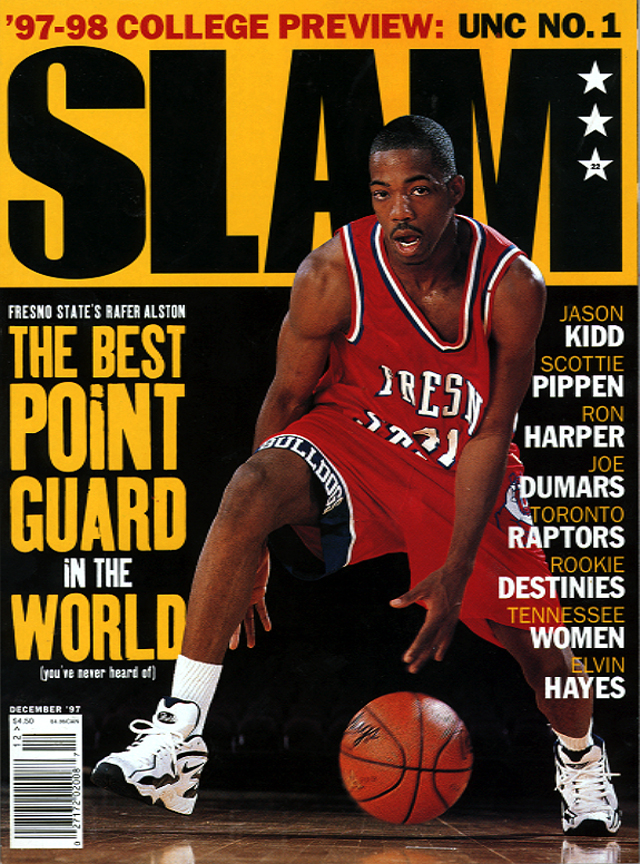

After scores of texts and an inability to schedule a face-to-face interview in New York, current Houston resident Rafer Alston and I are talking on the phone. And, as ever, the born leader out of South Jamaica, Queens who got his first dose of national fame after appearing on the cover of SLAM in 1997, has a lot to say.

Between the SLAM cover, which proclaimed the incoming Fresno State junior “the best point guard in the world (you’ve never heard of),” the AND 1 Mixtapes and Tours and the NBA career that lasted from 1999-2010, Alston’s story was oft-told. But with the demise of streetball as a crowd- and television audience-drawing branch of the sport, and Alston’s somewhat-rushed disappearance from the League, it’s a story that has already been forgotten by many. And, given the fast-paced media world of today and the millions of new young fans basketball gains each year, Rafer’s is a story many may not know at all.

So, with the help of the 37-year-old Alston and a couple of the folks he impressed along the way, we’ll re-tell it.

“The handles and the passing that I became known for, that developed from playing a lot. And also watching a lot,” he says. “Bouncing around the city, going to different playgrounds, different parks and noticing all the stuff that gets fans out of their seats. I watched local guys that made it big like Pearl Washington, Rod Strickland, Mark Jackson and Kenny Anderson. Plus local guys that didn’t make it out, like ‘Master Rob’ [Robert Hockett] and ‘Dancing Doogie’ [Gerald Thomas]. Doogie was tough. There were so many kids who were so gifted that never made it to college or the NBA.”

Continues Alston, “I played most of my pick-up games in South Jamaica, but I played in tournaments all over the city. I was known in every borough by the time I was 11 or 12 years old.”

Long-time Queens (NY) Cardozo coach Ron Naclerio, who was also teaching and coaching at local middle school IS8 when he met the 10-year-old budding baller, remembers what he was like. “Rafer came to me and said I should watch out for him when he got to IS8 in 6th grade,” Naclerio says. “And sure enough, he showed up and we’d work out every morning for all three of his years there. He was a really good young player and a knowledgable kid.”

Between Alston’s willingness to go anywhere for a run, and Naclerio having a team that played in the EBC at Rucker Park in Harlem, a logical next step for young Rafer appeared. “He was 12, but they let him play after I told them he and Stephon Marbury were the two best young guards in the city,” remembers Naclerio. “His nickname at first was ‘Shorty,’ because he was small. By the time he was 14 he was playing 20 minutes a game there, and that’s when all the ‘Skip to my Lou’ stuff started.”

Ah, yes. The “Skip to my Lou stuff.” The nickname (often shortened to just “Skip”), bequeathed on him by one of Rucker’s ubiquitous announcers after the flashy ballhandler had skipped his way up the court while dribbling, started to travel throughout the five boroughs.

“He picked the ballhandling stuff up so easily,” says Naclerio. “When I was working him out, I kept coming up with new moves and dribbles for him to try. He loved all that and took it 100 levels beyond. He found all that stuff intriguing, and some of it just came natural, but he also practiced it a lot.”

It was a recipe for crowd-pleasing, and by 17 years old, Skip was considered a must-watch sensation. As Bronx product and 16-year NBAer Rod Strickland explained to SLAM back in the day, “One of my partners kept telling me about him, so I went over to Rucker to see him play. And right away I knew he was something special. You know how they play over on 155th, a little clownish at times with all the tricks? But Skip just had incredible instincts. His passing ability, his dribbling ability, and then, he was really playing defense, too.”

Says Alston today, “Playing at Rucker Park was very special. I always felt comfortable on that court, and the crowd always made me feel good.”

While he’d become a sensation in the unsanctioned hoops world, a messy home life and erratic school performance kept his name under the radar in the more organized sector. But poor grades and limited appearances for the Cardozo varsity did not mean Rafer didn’t care about making it to college or beyond. “Not at all,” he professes. “I didn’t do great in school at all, but I did enough to get into JuCo and then DI because I wanted to help my family. I understood that there was life outside of the inner-city. A lot of us that grew up playing basketball in the Chicagos, Detroits, New Yorks…we had it rough. Basketball and school were a way for us to get out of that.

“The era before me, sometimes becoming famous and making money in the streets was enough for guys,” Alston continues. “I mean, they could make more on the streets than they could in the NBA. Some did have shots at the pros but just didn’t develop the skills they needed. Some didn’t even try. But becoming famous on the city playgrounds was never enough for me; I always dreamed of making the NBA. Even if I played what they used to call ‘the city game,’ I was a student of the game, and I always knew how to run a team. A lot of stuff that playground guys struggled with when they got to a college or pro team, I didn’t have those problems. Coaches were always surprised by how well I knew the game.”

Says Naclerio, “There was just something about the kid. For one thing, even though his academic transcript wouldn’t indicate it, Rafer is very smart. He did what he had to do to play in college, and I always wanted to help him as much as I could.”

What Alston “had to do” was earn a GED, stay out of serious legal trouble, move to California and spend one year at Ventura College and two at Fresno City College, where he redshirted one year and then averaged 17.3 points and 8.6 assists per game while also earning his Junior College degree the next. The three-year odyssey in Cali was enough to earn Alston a DI scholarship from Jerry Tarkanian and Fresno State…and enough for SLAM’s primarily New York-bred staff to run by far its craziest cover up until that point (and maybe til today, even with Chamique Holdsclaw and a burning ball in our more recent past).

Ronnie Zeidel, then SLAM’s Advertising and Promotions Director and now the CMO at Prolater, was a Cardozo grad who saw an opportunity for SLAM to make a statement. “I wanted Rafer on the cover and I remember talking about it with Tony [then-Ed. Gervino, who is now running the show at Billboard] who was beyond open minded and gave it real thought,” remembers Zeidel. “We brought it to publisher Dennis Page, but we thought he wouldn’t be into it because he was always very careful with who we had on the cover from a sales perspective. But Dennis was hip to Skip and we all went and saw him at Rucker and followed him closely through JuCo, and eventually we were all into the cover idea. I remember that Naclerio freaked out when he saw it, and Skip was always so appreciative of the cover.”

“I just know the timing was perfect and that I was really entering the spotlight,” says Alston of the cover. “I was already a playground legend, and I was going to play for a legendary coach in Jerry Tarkanian who was really just getting back into coaching with Fresno State. And then the SLAM cover came along. I was asked to sign that cover a lot, and well into my NBA career, like, usually on the road at hotels. And I still have it at my mother’s house. Whenever I look at it I laugh because of how young I was, and how strong—I was really working out that summer [laughs].”

On a Fresno State team with too much talent and not enough basketballs to go around, Alston showed that his handle and passing ability were high-major caliber, but his jumpshot and ability to get along with others (even if it was the others’ fault) were considered question marks. Technically Rafer had a year of eligibility left, but it wasn’t clear that Fresno would let him use it, and the roster was a mess, so at the 11th hour, he declared for the ’98 Draft. “You had to put your name in the Draft by mail, and the letter had to be mailed by midnight on a certain date,” explains Naclerio. “I remember we finally decided he was going in the Draft on the last day, and me mailing the letter from the big post office on 34th Street (in Manhattan) at 11:51 pm.”

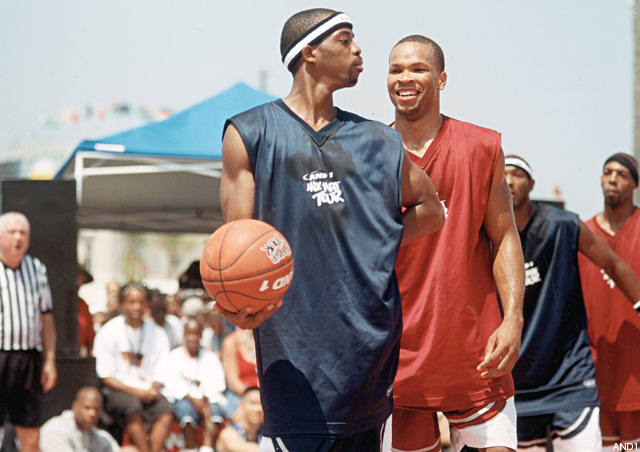

Still a bit of an unknown to the basketball establishment, Alston slipped into the second round, where the Bucks selected him 39th overall. He actually spent the ’98-99 season in the CBA, and then the better part of ’99-02 buried on the Bucks bench. Not exactly a hero’s welcome to the League for a player who was simultaneously becoming a streetball celebrity thanks to the ’99 release of the AND 1 Mixtape, Vol. I, which was effectively a loop of sick moves concocted by a young Skip.

“Not being in the rotation in Milwaukee was discouraging, but I was around players like Sam Cassell, Haywoode Workman, Vinnie Del Negro and coach George Karl. I really learned about the game, and how to be a professional. People probably stereotyped me as a ‘playground player,’ but I always tried to show I could run a team,” Alston says. “And then, the rolling out of those tapes kind of caught me by surprise, but the Tour that came about after was amazing. We were giving performances all over the country that people had never seen. We were rock stars, doing something that had never been done before.

“The fact that fans in the NBA knew me more as ‘Skip to my Lou’ was fun. Only naïve people look down on players who played on the playground. Coaches and GMs, they need that style of play on their team. Where did Isiah Thomas learn to play? The tough streets of Chicago. They can say this, that and the third about playground basketball, but I don’t think fans would even watch as much if not for that style of play.”

Says Naclerio, “What’s great about Rafer is that most guys become ‘legends’ at the end of their careers. Rafer was a legend at 17…and then he made the NBA. It’s like, Superman was Skip to my Lou, who could do anything on the playgrounds. Clark Kent was the Rafer Alston who got the job done in the NBA.”

Sure enough, once Alston got a job, he got it done. A successful 10-day contract with the Raptors in ’03 begat an extension til the end of that season, and then, in ’03-04, a full-season stint with Stan Van Gundy and the Miami Heat. For the first time, the 6-2, 171-pound Alston played 82 games in a season, and he showed he could handle the load, averaging 31.5 minutes, 10.2 points, 4.5 assists and 1.4 steals a game.

The numbers only grew from there, as the Raptors were impressed enough to bring him back to Canada, to the tune of a long-term contract and a starting point guard position. A 14.2/6.4/1.5-per season in TO was followed by another trade, this time to Houston and another Van Gundy.

“We traded for Rafer to be our starting point guard,” remembers current ESPN NBA analyst Jeff Van Gundy. “He had just had a good year in Toronto and my brother Stan had spoken highly of him after their time in Miami. You’re always looking for guys who love the game and have a high basketball IQ, and Rafer had those. We were building around [Tracy] McGrady and Yao [Ming] and we needed a point guard to set the tone on offense and defense. He played with a speed and quickness that we needed.”

Continues the always entertaining JVG, “I wasn’t really into that—What do you call it, the AND 1 Mixtape Tour?—until Mark Jackson’s brother [Escalade, RIP—Ed.] told me about it. Then I became a fan of his and that guy Grayson, ‘The Professor.’ I even went to one of their practices in Houston. But that was after Rafer. So I knew he’d played there, but I never saw him. I just knew I was happy with the job he did for us. And look, after I got fired, he started for Rick Adelman on a team that won 22 games in a row.”

Alston’s successful run in Houston ended with a trade-deadline deal to Orlando in ’09, where he provided essential depth to the Magic. Rafer took over the starting PG spot from injured All-Star Jameer Nelson and teamed up with Dwight Howard and coach Stan Van Gundy to lead the Magic to their second-ever Finals appearance. “That was an electric run we had in Orlando,” Alston says. “Me and Coach Van Gundy were a great match. I was grateful I got to make it to the NBA Finals.”

A couple days after those Finals, however, Alston was dealt to the New Jersey Nets, and by the spring of 2010 he was out of the NBA forever. “People want a storybook ending, but the right time is when the player thinks so,” Alston philosophizes. “That was the right time for me. Once you approach 33, 34 in this League, you’re looked at like you’re a dinosaur unless you’re a Tim Duncan and Manu Ginobili. And they’re the exception because they’re on the Spurs—with the perfect team and the perfect coach.”

There were stints in China and the D-League, but Rafer hasn’t been heard from in the States too much since he left the L. “Now I’m doing a lot of coaching,” he says. “I did some AAU in New York and I’m starting to develop a program in Houston. I bounce to China once in a while for clinics, exhibitions. Sometimes stuff with kids and fans, but sometimes to work with guys who actually play in the CBA.”

Says Jeff Van Gundy: “Rafer has a great passion and enthusiasm for the game. One or two times a year, that can lead to too much volatility, but for the most part it’s a great thing. My brother and I spoke about Rafer positively all the time. My brother even named his dog after him! Skip. I think he had a terrific career, and I think he’ll be back in the NBA as a coach in the next few years.”

Chuckling again about his unlikely appearance on our cover, Rafer says, “I may not have become a college All-American at Fresno State, but I played 11 years in the NBA, so I don’t feel like I let the SLAM cover down.”

Not at all, Skip. Not at all.