Before bombs leveled the supermarket owned by his parents, before he and his family, like herds of other Serbians, were forced to flee their home in the Croatian town of Požega for the simple reason that they were Serbian and the men raining fire down upon them were not, before a bitter and deadly civil war throughout the final decade of the 20th century tore apart what used to be Yugoslavia, Peja Stojaković would spend a few nights every year watching TV in his family living room, fighting the backs of his eyelids to stay awake.

He was a kid back then, about 12 or 13 years old, in love with basketball and trying to soak up as much of the NBA in whatever way he could. That meant tuning in for whatever odd game trickled out of the U.S. and onto Yugoslavian TV, usually matchups featuring the era’s top teams: Detroit’s Bad Boys, Bird’s Celtics, MJ’s Bulls.

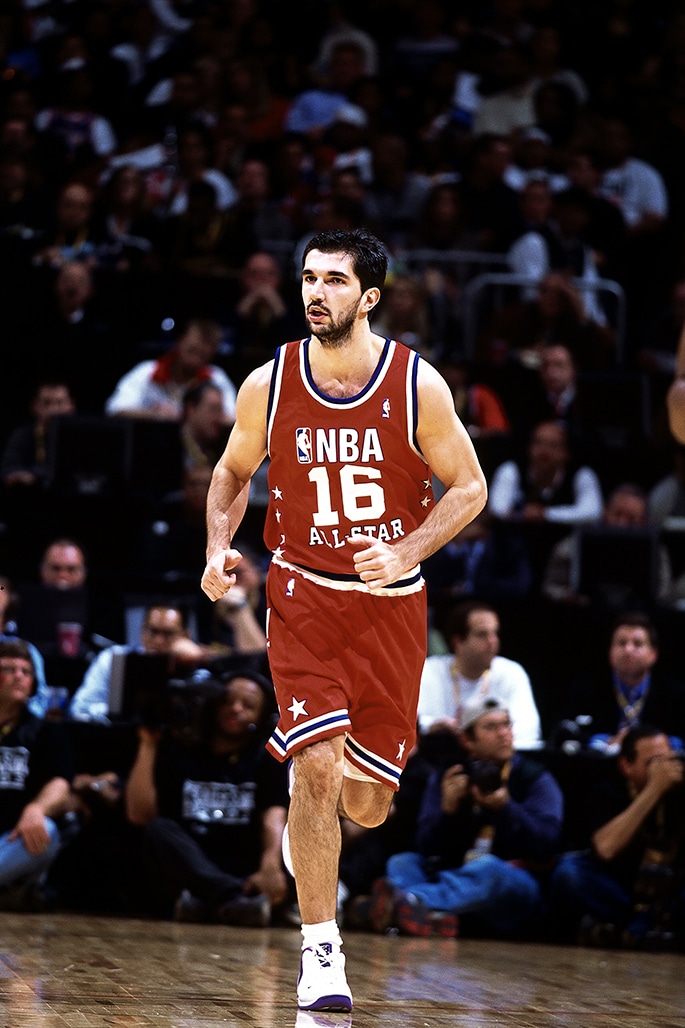

But nothing excited Peja quite like All-Star Games. They offered a chance to see all the League’s best players facing one another on the same floor. The games didn’t tip-off until around 2 a.m. local time and so Peja’s parents would try repeatedly to throw him out of the T.V. room and back to bed.

There were no Europeans in those games. Peja would have to wait until 1993, when he was 15, to witness Germany’s Detlef Schrempf break that barrier. But he was stubborn and persistent and also obsessed with the NBA, which usually meant he got his way. As he sat there and watched Magic majestically push the ball up the court and Chris Mullin stroke jumpers from the outside and Charles Barkley do a little of everything, he couldn’t help but dream of one day wearing an All-Star Game jersey himself and performing on that stage.

He never imagined that his dream would wind up underselling his true impact on the game, that he’d go from refugee to NBA star and help dispel some popular-yet-ignorant stereotypes along the way.

Stojaković has just completed a mundane meeting on a mundane mid-season afternoon when he answers his cell phone. His playing career ended seven years ago. But now, after a stint that a former teammate once referred to as “civil life”—meaning life outside of the NBA bubble, which for Stojaković consisted of some restaurant investments and, somehow, a solar energy project in Greece—he’s returned to the NBA and to one of his former teams, the Sacramento Kings, for whom he holds the fancy sounding official title of Director of Player Personnel and Development. There, even the most boring meetings leave him feeling fulfilled.

“It just felt right,” Stojakovic says. “That other stuff gave me good experience but they didn’t drive me, it didn’t excite me.”

Basketball does, partly because of what the sport has meant and done for him and also what it’s allowed him to do for others.

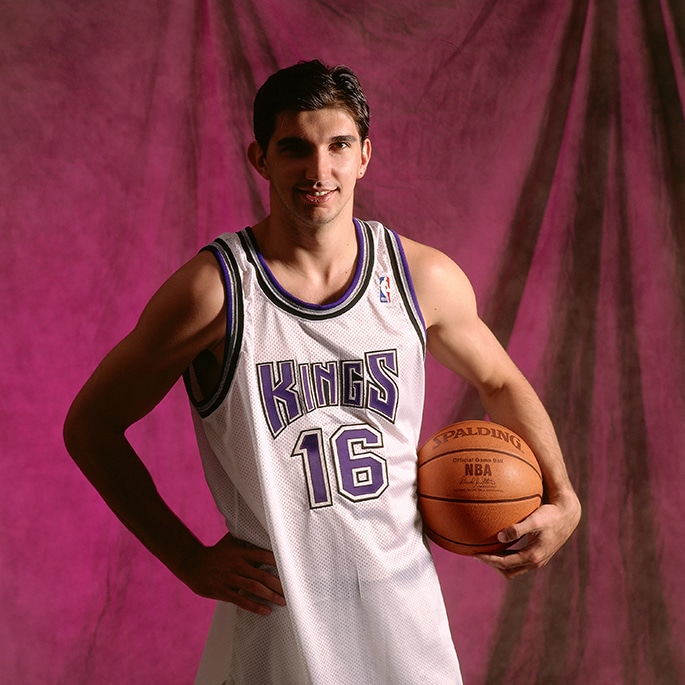

Stojaković’s NBA career technically began in 1996, when the Kings drafted him 19th overall, though it took two years for him to make his NBA debut. When he made that debut during the 1998-99 season, he was a starring player on one of the NBA’s best and most enthralling teams. A team, stylistically, very much ahead of its time. “We played like today’s Warriors, only we didn’t shoot the same volume of 3s,” Stojaković’s former teammate Doug Christie says. They’d pass and cut back door and run and shoot and when it came to shooting, Stojaković was, well, king—even if his form resembled something you’d see on a playground full of novices.

Instead of keeping his right shooting arm in a tight “L” and raising the ball straight up, he’d swing his elbow out past his hip and swipe the ball across his face before slinging it towards the hoop. Instead of keeping his toes pointed forward they’d bend inwards, bringing his knees within inches of touching.

Textbook it was not, and yet something about that crooked jumper was so smooth, so fluid. It’s hard to make ugly look pretty, but Stojaković was able to do exactly that. He could also handle the ball, too, despite being a 6-9 forward, and during the early 2000s he torched nets for a Kings squad that was perpetually competing for titles, but also perpetually coming up just short. (Some shady officiating certainly didn’t help, but that’s a story for another day.)

As time marched on, and that electric Kings team was eventually dissolved, a pair of Stojaković misfires served as representatives for that team’s overall failure, and, to many, as symbols for why many European players couldn’t be trusted when it mattered most.

It was Game 7 of the 2002 Western Conference Finals. Trailing the Lakers—the Kobe-Shaq defending champion Lakers—by 1, at home, with about 13 seconds remaining, Kings forward Hedo Turkoglu drove and dished to a wide open Stojaković standing in the left corner. His shot sailed over the rim by about two feet.

Sacramento wound up tying the game up, only to find itself in a similar situation in overtime. With 10 seconds remaining and trailing by 2, Kings guard Mike Bibby drove and dished to Stojaković, once again wide open but this time on the left wing. He cocked and flung the ball towards the basket. It missed the entire rim and flew off the backboard into the waiting hands of Lakers forward Robert Horry.

“You obviously regret parts of your career and you remember the stuff that didn’t go well more than the stuff that did,” Stojakovic says. “But honestly, it’s not like I’m thinking about those shots every day. You just move on and try to make the best of the next opportunity.”

And anyway, Stojaković was chasing something greater.

“I wasn’t given promises in my career,” he says. “I was always proving myself, every day of every year.”

The call came in about four months prior to that Game 7. It was around 8:30 in the morning and Stojaković was on his way to a local school for an appearance when his phone rang. It was a Kings public relations staffer and he had some news: Stojaković had been named a reserve member of the Western Conference All-Star Team. He’d also be competing in the Three-Point Contest, which, of course, he’d wind up winning, and repeating as champion the following year.

But it was that first All-Star Game honor that has always held the most weight. After all, as a kid it was the game itself, not the contest surrounding it, that led to him fending off his scheduled bedtime calls so that he could watch.

“Being part of that game, it makes you feel like you’re part of something big,” Stojakovic says. “Especially for me, being from Europe.”

Stojaković is wary of labeling himself a trailblazer. He’s more of the deferential type, instead tossing out other names like Dirk Nowitzki, Manu Ginobili and Pau Gasol. Push him, though, and he’ll concede, just a bit, and admit that “I think we”—it has to be “we”; “I” won’t due—“kind of helped open those doors for NBA scouts and management to have more trust in bringing kids over from Europe.”

Those who followed in his footsteps are aware of this as well.

“He was one of the Europeans who kind of paved the way for me and others,” says Kristaps Porzingis, the 22-year-old Knicks star and Latvian native.

It’s not just that Stojaković played and excelled. It goes back to a word, soft, and the way it was so often thrown at the feet of European players during his career. America, despite its welcoming slogans, has always had some not-so-beneath-the-surface issues with foreigners. Fans, players and executives questioning the toughness of European basketball players has always been how that fear has manifested itself in the NBA.

“I don’t even know where that came from, but it was definitely something that was talked about back then,” Christie says.

It didn’t matter that Stojaković grew up a refugee in a war-torn country, or that those two missed shots against Lakers came in a series where he was hobbling around on a blown-up sprained ankle and yet had still played 25 minutes that evening—the opposite of soft, however you choose to define what the word even means.

“I haven’t seen many people fight on NBA floors,” Stojaković jokes when asked whether the barb bothered him. “I never thought about it that much. I always looked at it that you step on the floor and do the best that you can. I don’t think you can label somebody like that. I don’t even know what soft means. At the end of the day it’s a game and either you can play or you cannot play. My coach when I was young used to talk about our ceiling. We all have different ceilings and your goal is to reach it.”

Stojaković eventually reached his. He responded to that loss to the Lakers with three brilliant seasons and even finished fourth in the 2003-04 MVP voting. He played 15 years in total, retired with a scoring average of 17 points per game and eventually did win a title, with Dallas, in the final season of his 15-year career.

But acknowledging that he believes he fulfilled his potential is about as far as he’s willing go when it comes to legacy talk. He’s not interested in any special praise or a slap on the back. The way he sees it, he worked hard, enjoyed some luck, hit some shots, missed some shots and most of all relished every day along the way. And perhaps that’s all true. Perhaps he was just a talented and lucky man who happened to be in the right place at the right time. But that doesn’t diminish what he did for NBA, and, if you believe in such tangential connections between sports and society, the country as a whole.

The interview wraps up and Stojaković hangs up and returns to his job of Kings executive. He’ll no doubt check in with his boss, general manager and Serbian native Vlade Divac, and perhaps they’ll review a directive from Vivek Ranadivé, the team’s Indian-born owner. Or maybe they’ll speak with one of the handful of GMs born outside the United States. Who knows, maybe one of the 113 international players, none of whom are viewed as soft, currently suiting up for NBA teams is on the trade block? Or maybe there’s a kid in some far-off place who needs to be scouted, a kid studying clips of NBA players dreaming of the day he, too, might change the game.

—

Yaron Weitzman is a Senior Writer at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @YaronWeitzman.

Photos via Getty Images