There was a moment in NBA history when the New Jersey Nets were a truly dominant franchise. Six straight trips to the Playoffs. Back-to-back Finals appearances. Seven straight years of at least one Net making the All-Star team. Five straight 42+ win seasons. Five straight seasons of having at least a top-6 defense. Three straight division titles. Three playoff sweeps. And a 20-7 record against the Knicks.

Between July 2001-June 2008, the Nets were a legitimate threat to the rest of the League. And it seems like the franchise and the rest of the world has worked really hard to forget about the time that Kenyon Martin, Richard Jefferson and Vince Carter ruled the skies.

After their incredible run in the 2000s, the Nets finished their time in NJ with disastrous seasons, including a 12-win campaign. They have yet to make up for that struggle. Instead, extreme mediocrity has become the standard for the team’s time in Brooklyn.

Oh, the Brooklyn Nets. What a sight to see.

Sure, New Jersey isn’t a sexy place to play. Continental Airlines Arena, where Jason Kidd used to throw oops to the rafters, was in East Rutherford, smack-dab in the middle of the New Jersey Turnpike. The parking lot was huge and it took a walk-and-a-half to make it from your car door to the arena entrance. It was a world away from civilization. It seemed impossible that New York City could be only 15 miles west.

But at the very least, the few people who did show up were fans. Not the Jay Z, Fat Joe-type of fan. No, New Jersey Nets fans were pretty much always local generations of families. Families that had rooted for guys like Kenny Anderson, Drazen Petrovic (RIP), Derrick Coleman, Stephon Marbury. There was a little bit of tradition inside the CAA.

Which just isn’t the case in Brooklyn, yet. Going to Nets games isn’t about the Nets. People show up to watch the opposing team or they show up because it’s something to do. You’d be lucky to find more than a handful of people who would know who Richard Jefferson is at Barclays Center. You’d be lucky to find 50 people that know where Brook Lopez went to college. And good luck finding anyone who remembers Kerry Kittles.

It’s tough to figure out why a franchise that hasn’t had a star since Carter was traded in 2009 would run away from a history that had thrilling highlights and so many wins. Winning. Winning in a way that made young kids fall in love with the game.

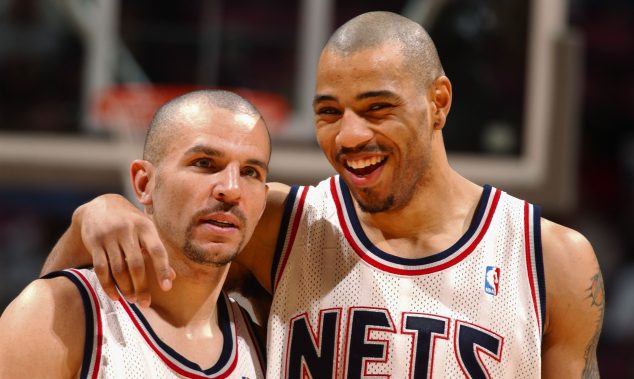

Kidd created a team-first atmosphere, with a focus on defense. He would sprint to pick up teammates that had fallen to the court. He would do little fist pumps and hops when a teammate did something well. He would bust his ass to get rebounds and loose balls. He made people better than they ever should have been. And there were so many dunks. Most importantly, though, the Nets played hard every night.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SzUGpvLfqww

The Brooklyn Nets’ biggest problem has been heart and desire. In the team’s first season in the borough, offensively challenged Gerald Wallace and Reggie Evans had to start just to pump some life into the team. The Boston Celtics trade that has stripped the team of a present and future was necessary just to have Paul Pierce’s and Kevin Garnett’s competitive fire in the locker room. With Deron Williams, Joe Johnson and the last remnant of Jersey, Brook Lopez, the Nets had three guys who were too cool for school.

Kidd’s first right-hand-man in Jersey was Kenyon Martin. He was the No. 1 pick in the 2000 Draft, coming out of Cincinnati, but he always played like the underdog. He always played with something to prove.

At 6-9, 230 pounds, Martin zoomed around the court, running and jumping from end-to-end for 48 minutes. There was never any question about how badly he wanted to win. He gobbled up rebounds, pinned opponents’ shots against the glass and punched dunks in the face of defenses. He was pure, raw emotion, howling to the moon after each and every play. He used to pull his jersey off his chest and pound his heart, or hold up a finger to his ear, begging the New Jersey crowd to show him and his teammates some love. It always worked. Martin was the heart and soul of the teams that went to the Finals.

Watching him play was infectious. There was no way to not be a fan. He played so hard. Combined with the high-flying Jefferson, the Nets were getting steals and fast breaks seemingly every other time down the floor. While they lived on daily highlight reels, they were also racking up Ws.

Then, after K-Mart left for Denver, the Toronto Raptors traded Carter to the Nets on a December night in 2004. Things changed, but things were the same. Kidd was still leading the Nets to the Playoffs and playing at an All-Star level. Jefferson had matured into a valid third option, able to shoot and pass off the dribble. Instead of running teams into the ground with Kidd/Martin pick-and-rolls, the Nets transitioned to open the floor for Carter to create, both off the dribble and the catch. Jefferson relieved the pressure off his All-Star teammates well enough for the Nets to continue their run of the East.

As Kidd’s second right-hand-man, Carter was incredible. His on-court imagination somehow topped Martin’s on-court aggression. He would try ridiculous corkscrew layups and contested fadeaways. He had no fear, and no ceiling for his in-game dunks. Carter scored in every way possible. He continued the aerial assaults that made him famous in Toronto and added a three-point shot with seemingly limitless range. Between 2004-2009, Carter made 343 shots from 25+ feet away. He also consistently hit clutch shots and game-winners.

Kidd and the Nets found a way to become more entertaining after Martin left. Instead of the power of Martin, the Nets used the magic of Carter, leaving fans feeling inspired, like anything was possible on the court. With Carter and Jefferson on either side of him, Kidd’s passing and patience improved. There were just as many dunks as before, and even though there weren’t as many wins as with Martin, Carter made the Nets more dynamic on offense. For all of Martin’s intangibles, he couldn’t shoot from further than 18 feet, and he wasn’t an elite passer. Carter proved to be an overwhelmingly unselfish passer, often going out of his way to find Jefferson in the corner or streaking to the tin.

With Kidd as the ever-constant stone face, unflappable in big moments, Carter filled in for Martin as the heart and soul of the team. He was tough as nails. After big dunks and shots, Carter would let out a primal roar, accompanied by a lethal stank face.

The Nets had a pair of basketball geniuses in Kidd and Carter, and an acrobatic artist in Jefferson. They made the game fun. There were no restrictions.

For six straight years, the Nets could beat any team in the L. Kidd was the best point guard in the world, Carter and Martin were certified assassins. Jefferson was a walking SportsCenter clip. Throw in the cameos from Jason Collins, Dikembe Mutumbo, Alonzo Mourning, Cliff Robinson, Lucious Harris, Keith Van Horn, Brian Scalabrine, Nenad Krstic, Bostjan Nachbar, Zoran Planinic, Antoine Wright, Marcus Williams, and of course, Kerry Kittles—those guys rounded out teams that were professional, that played the right way, that didn’t quit.

Why would the Brooklyn Nets franchise want to ignore all of that? That was the height of their organization to date. Is it because Brooklyn’s cooler than New Jersey? Because the Brooklyn version sells more shirts and hats? Because black is more sleek than navy blue?

Mikhail Prokhorov has been preaching championship since the day he bought the Nets. He hasn’t even sniffed one yet. Instead, he and Nets management have decided to forget about the times that Kidd had them within a few games of going down in the history books. He should be celebrating them.

The New Jersey Nets are now just a memory from what feels like a lifetime ago. Continental Airlines Arena is closed now. Lopez is the last Net standing from the swamp. Kidd isn’t with the organization anymore. Carter and Jefferson are in the twilights of their careers. Martin has already hung up his sneakers.

The New Jersey Nets are gone, and mostly forgotten. Nobody seems to care.

—

images via Getty