New York City is known for being the birthplace of the world’s greatest point guards. So why are there so few of these playmakers in the NBA today? We try to get to the root of the problem.

The second Saturday afternoon of 2015 is a frigid one. The inside of Madison Square Garden can’t even get warm. This is attributed less to the Knickerbockers owning an NBA worst 5-34 record via an offense that’s a snow cone of a triangle and more toward the building being swarmed by January drafts. On court is another story. The visiting team is hot. They’re up 31 points at half. Their point guard is cooking. He has 20 of their 61 points.

He flies past Celebrity Row, pounding the rock. With a screen between he and his defender, he jukes a couple in-and-out dribbles with the right hand and crosses left around the screen for a pull-up. Bucket. A minute later, he drains a three. He rebounds, shakes defenders off his path, reaches the cup at will; the smallest man on the court is all smiles and swag while executing a scoring-by-exquisite-ballhandling clinic. It’s as if he’s balling in West 4th’s “The Cage” instead of earth’s greatest sports arena. Truth is: there’s no better city to floss this style of point guard play than in its home.

The Big Apple has always been a womb, incubator, playground and university for basketball’s elite floor generals. It’s where the Point God was birthed. From Bob Cousy to Lenny Wilkins to Nate Archibald to Rod Strickland to Stephon Marbury, every NBA decade saw the five boroughs represented at the 1. While the streak continues, the new millennium has seen its volume fade. This season, nobody’s Top-5 NBA Point Guard list boasts a New Yorker. In fact, there’s only one NYC point starting in the entire League…and he just served the Knicks 28 points and 5 assists in three quarters. “Wow,” begins Bronx native Kemba Walker after his Charlotte Hornets backhanded NY their 35th loss. “I didn’t even realize I was the only one starting. Damn.”

For other natives, this is not a surprise. “It hurts my heart to see where New York basketball is,” says playground legend and retired 11-year NBA PG Rafer “Skip To My Lou” Alston. “It’s sad. I go home and I’m still looking. Show me a bona fide New York City point guard.”

***

The decline of the NYC point guard began at its peak. In the late ’90s, city hoops was gifted global marketing via “mixtapes”—camera footage of “oh shit”-inspiring park play roughly edited into a VHS spin. Of these compositions, the tiny documentary Soul in the Hole was the proverbial “Purple Tape”—mainly due to its star: Fort Greene Project’s Ed “Booger” Smith, a raw 5-8 wizard with the rock who rarely went near his high school but could always be found on a court. AND 1 seized the moment. The sneaker company launched its first mixtape, introducing the world to Rucker Park’s legendary tournament, the Entertainer’s Basketball Classic, and the franchise’s initial poster boy, the aforementioned Queens-bred Skip To My Lou. Streetball was at a high, with tours, ESPN and Emmys in its future. The city was ready for one of their ankle breakers to shake David Stern’s hand.

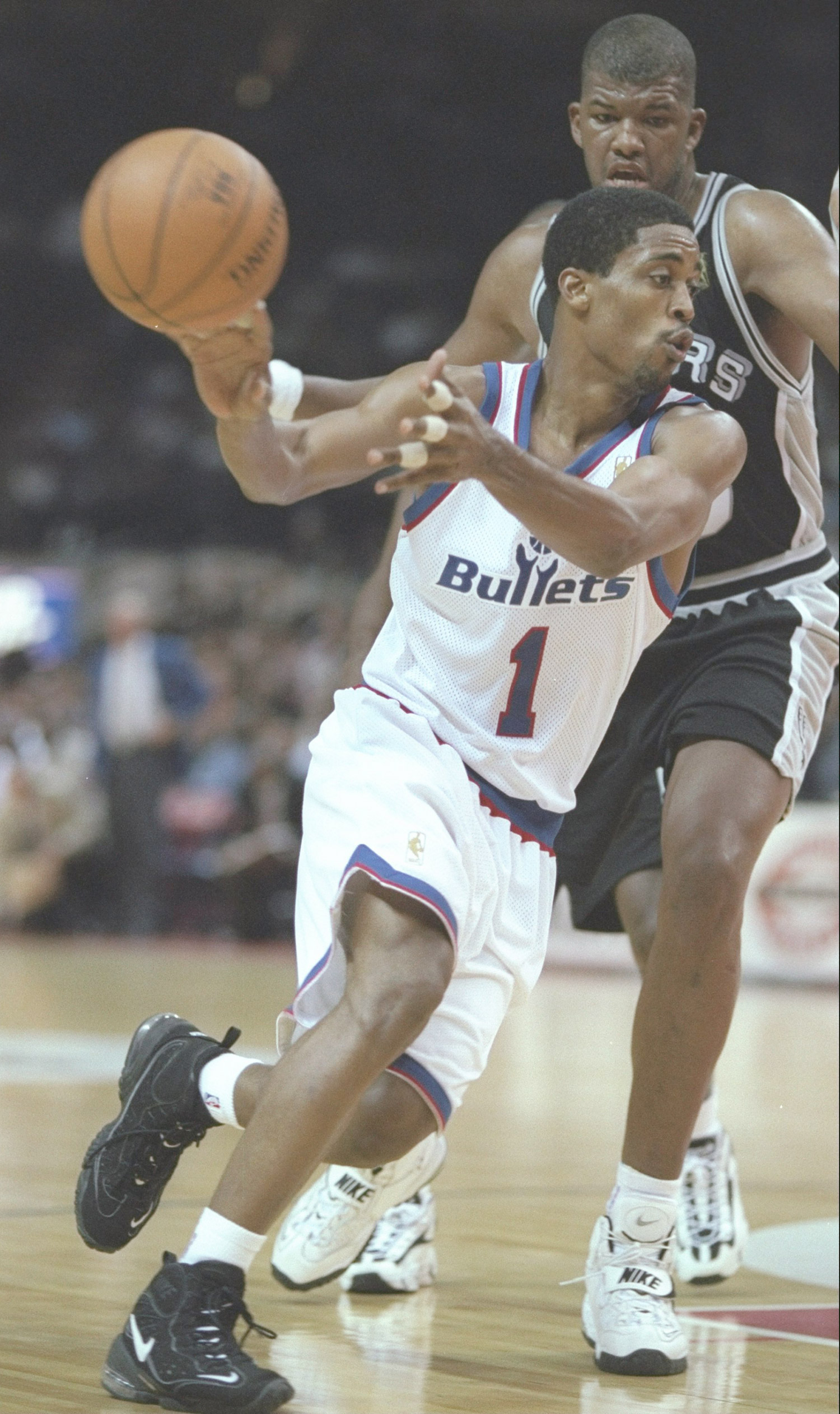

While Starbury’s Draft day inspired much local pride, it was expected since he was polished by the age of 12. The streetball era’s first blacktop legend to make the A was Harlem’s All-American, Providence standout and owner of possibly the lowest crossover ever, God Shammgod. God rocked future pro and NCAA champ Mike Bibby in 1997’s Elite 8 before the Washington Wizards picked him 45th in that year’s Draft. By 1999, Shammgod was in the CBA. A year later, Poland. “I really thought Sham was gonna make it,” says Anton Marchand, an NYC basketball guru. “He had everything: handle, smarts, courage. I was pulling for him.”

The year after God was drafted, Rafer squeaked into the L as the Milwaukee Bucks’ second-round pick and was immediately sent to the CBA. Although eventually called up, he was nailed to the bench by the Bucks’ coach, George Karl. Skip To My Lou was soon put to rest. “Rafer could go anywhere on the court with the basketball,” says Karl. “Sometimes he would go in bad places with that talent and get in trouble with big guys or pick and roll coverage. I’m just not a fan of making an easy basketball play difficult, but maybe that is streetball.”

Once the century turned, NYC PGs were no longer in vogue. In 2000, Brooklyn’s Ed Cota graduated from UNC as the Tar Heels’ all-time assist leader but couldn’t attract a single NBA team. A few St. John’s handlers were drafted—Queens’ Erick Barkley (No. 28 in ’00) and Brooklyn’s Omar Cook (No. 31 in ’01)—but, similar to their jumpers, neither could stick. If the ’90s perception was that white men couldn’t dunk, the aughts offered its own. “People always say New York City guys can’t shoot,” says Walker. “There was a point where I wasn’t consistent, and even now I’m not super consistent, but it’s getting better.”

“The jump shot is one thing that plagues us in NY because we want to play the city game and drive,” says Alston. “A lot of us will get to the NBA but that jump shot is needed to stay.”

God Shammgod views his short NBA stint a little differently. According to him, his Wizard coaches oppressed his natural and unmatched gift for handling the rock. With his biggest strength, penetration, stripped away, his weaknesses became glaring. “When I got in the League, they made you feel bad for dribbling so good,” he says. “Now it’s not over-dribbling. Today, [NBA] coaches are telling point guards they have to have a never-ending dribble.”

After the League spent several years chipping away at physical defense (i.e. contact by defender with elbow), scoring rose and an unlikely Steve Nash won consecutive MVPs. Today’s NBA now runs on the engine of flashy, adept handlers, who can score, dime and entertain in bunches. “When I first came in the League, the point guard was more of a pass-first position,” says Hornets assistant coach and perhaps the finest shooting point guard of all time, Mark Price. “Now it’s wide open. There’s more opportunity because of a lack of post players.”

“I’d rather see my point guard be a little crazy than too conservative and fundamental,” says Karl, former coach of killer PGs like Gary Payton and Sam Cassell. “I want my point guard constantly attacking and making good decisions.

At press time, the top-four teams in each conference start a PG with an NY-inspired game, most notably Dallas’ Rajon Rondo. When Chris Paul is asked who inspired him to play the 1, he names God Shammgod. Says Sham, “Every point guard that came out of New York was a scoring point guard. Every top NBA point guard now is a scoring point guard. Look at Stephon Curry. He looks like he’s on 155th [Street]. Look at Kyrie [Irving]. What he’s doing is what Kenny Anderson was doing in college.”

***

So the question begs: If the basketball style raised by NYC is today’s preferred flavor in the NBA, why are less Big Apple playmakers employed? The answer to that conundrum is a layered one that lives deeper than the pro or collegiate level.

Before players are drafted or recruited or even in high school, they must develop a game in their neighborhood. Today’s five borough kids don’t occupy playgrounds and rec gyms like they once did. “We used to play a lot,” says NY legend and former NBA All-Star Kenny Anderson. “I’m from Queens, but I played in all the borough’s summer leagues. All the best point guards played there: Boo Harvey, Mark Jackson, Kenny Smith, Pearl Washington. We were always in the park.”

“Back in the day, we would eat and sleep basketball,” says Alston. “We’d play in the park, then go to somebody else’s park, come back to our neighborhood at night and play in our park again.”

A spin around the Rotten Apple reveals less packed courts. The city tournament just isn’t the hot ticket it used to be. Now it takes Kevin Durant or JR Smith to visit Harlem’s Dyckman Park for a citywide draw. When asked what snatched the attention of the New York youth, the consensus blames technology. “[New York] kids be in the house for six hours a day on Facebook and Twitter,” says Shammgod.

“They’re more focused on the Internet, the iPod, the video games, Instagram,” echoes Alston. “Working on your craft is no longer a priority.”

Millennials have more distractions than ever. Thanks to the Internet, smart phones and more broadcasting networks than ever, entertainment has tripled its offerings. Dreams have broadened—fashionistas are younger; the US President is darker. In the inner city, being an aspiring basketball player is not as cool as it was 20 years ago. “Rap music is [more popular] and being an entertainer is in,” says Anderson. “It’s just generational.”

Less playing means less repetition. Less repetition leads to less development—like a reliable jumper. “Back in the day, there was a game called Utah where it was you against maybe nine other people,” Marchand remembers. “You had to navigate to get through everybody. That helped guys figure out how to get where they wanted on court. Now everybody just works out with cones. But cones don’t move.”

“Kids are focused less on playing the sport and it hurts everybody,” says Mike Beckles, varsity coach for Brooklyn’s South Shore High. “It impacts players, their skill and the schools.”

A lack of committed student athletes has hurt NYC hoops, because the shoe company dollars go where the talent is. This redistribution of corporate support has empowered AAU recruitment and devalued high school athletic programs. “When I was in school, your high school coach would talk to all the college coaches,” says Anderson. “Now colleges talk to the AAU coaches.”

Alston feels the AAU recruitment eclipse is a pointless topic as the greater tragedy is college’s lack of interest in his city’s homemade. “When I was coming up, when a college coach wanted a point guard he was coming to New York to watch someone like myself on a playground. I’m talking Jim Boeheim, everybody. I don’t even see local college coaches looking in NYC!”

So the mystery of the NBA point guard from NYC can be credited to the erosion of a city’s bball culture. The foundation that is the playground isn’t the place of worship and betterment it once was. The young are preoccupied, thus the schools are enduring a drought. That All-City guard from Jamaica, Queens, is no longer on the level of his peers in Seattle (which currently boasts a handful of active NBA PGs).

There are NY natives like Taj Gibson, Tobias Harris and Lance Stephenson doing their thing in the L, but only that one Knick killer holding a candle for the Original PG Factory. “Of course I’m proud [to be the only starting NY point guard in the NBA],” says Kemba, now dressed and standing in a near empty MSG locker room, wrestling with his thoughts. “I just thought our dominance would’ve continued.”

Bonsu Thompson is a Senior Writer at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @DreamzRreal.