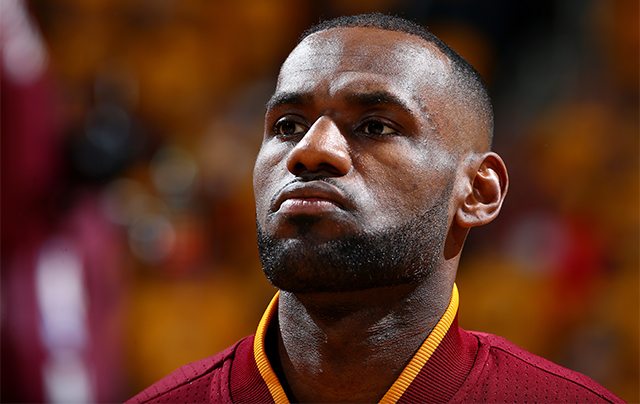

The Cleveland Cavaliers have just eliminated the Toronto Raptors in Game 6 of the 2016 Eastern Conference Finals. Despite the loss, the Toronto fans have stayed on to chant for their beloved team. It’s an inspiring sight, and in the middle of it all is LeBron James, who’s doing his post-game interview with Doris Burke. LeBron is advancing to his sixth consecutive NBA Finals, something that hasn’t been done since Bill Russell played for the Celtics in the 1960s. I’m watching this game with people I barely know but who I understand very deeply. These people come from different parts of the country, are different ages, genders, races, and sexual orientations. Many of us have next to nothing in common, and we all seem to see the world in a different way, but the one thing we do have in common is what brought us all together under the same roof. We all have severe Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). I’m sitting in an OCD treatment center, watching the 2016 NBA playoffs with my fellow patients, thankful that the game has ended before our counselors could walk in to enforce our 11 p.m. curfew.

Watching basketball in an OCD treatment center is a surreal experience. It was one of my few real connections to normalcy in a daily routine that was anything but normal. In the interest of privacy, I’m omitting the name of the facility. Let’s call it the Center. Last spring, I checked myself in to the Center for what would be nine weeks of round-the-clock treatment for my severe Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Treatment began at 8:30 a.m. every morning, ended at 6:30 p.m. every night, and as I said, we had to be in bed by 11 p.m. The treatment consisted of individual meetings with members of my treatment team—a behavioral therapist, a family therapist, and a psychiatrist—group classes with my fellow patients (there were about 30 of us in total), and four hours of exposures every day, which is the most important part of the treatment. There was a no-drinking rule that would get you expelled at the first infraction. There was a no-touching rule to prevent distracting romances budding up between patients (it happened anyway). The bathrooms were locked at all times to prevent compulsive washers from ritualizing unnoticed. Staff members cooked our meals, gave us our meds, and played board games with us at night to keep things upbeat.

This was intense, upsetting, difficult work in an entirely unnatural environment, and I watched as much playoff basketball as I possibly could to keep my spirits up. The Western Conference games often went past curfew, but I made sure to watch LeBron, my favorite player. I’m pretty sure I saw every Cavs game during those playoffs. I would discharge from the Center and return home just before the Finals started, so I watched the most iconic moments of the year—The Block, The Shot, the groin punch—back home in Brooklyn, but in my head, I’ll always associate that Cavs playoff run with my treatment.

Watching that last Raptors game, though, seeing King James rule the East for a sixth straight year, I was struck by how instructive this all was, by how the patients in that room could all take some comfort in what they were watching. Specifically, I kept thinking about an old, now-forgotten interview that LeBron gave with Chris Broussard in 2013, just as the Miami Heat were starting their three-peat campaign that would eventually end in a Finals loss to the Spurs and LeBron’s return to The Land. I think about that interview a lot. Here’s the part that keeps coming back to me:

LeBron: But I think the greatest thing about MJ was that he never was afraid to fail. And I think that’s why he succeeded so much—because he was never afraid of what anybody ever said about him. Never afraid to miss the game-winning shot, never afraid to turn the ball over. Never afraid. And that’s what I love most about him besides, obviously, the flying through the air and the tongue-wagging and the game-winning jumpers and the shoes and the baggy shorts. I think his drive and never being afraid to fail is what made him, and he would be unbelievable still today because of that.

Broussard: Do you ever battle a fear of failure?

LeBron: That’s one of my biggest obstacles. I’m afraid of failure. I want to succeed so bad that I become afraid of failing.

To me, this was a Holy Shit moment, and I was surprised more outlets didn’t run with it. This interview is not a major part of the LeBron narrative. Nobody talks about it. We analyze who LeBron follows and unfollows on Twitter, which teammates he leaves out of Instagram pictures, whether he wears a headband or not, and a host of other trivial matters that have no bearing on what he does on the court. But here was the greatest player of his generation admitting to the world that he feared failure, and that it was a significant obstacle to his success. This is real behind-the-scenes insight. This is the profound, self-reflective stuff star athletes never say in public. And nobody cared. It reminded me of the time Kobe Bryant admitted after his 2010 Finals Game 7 struggles against the Celtics that he “wanted it too much” and was trying too hard. Here, again, the best player in the world admitted that the magnitude of the biggest game of his life had gotten to him and affected his play, forcing him into a 6-24 shooting night. The Lakers won, though, so nobody ran with the story. Nobody cared that the league’s supposed most clutch player had just been humbled by the moment, by the stage, much like LeBron was against Boston in 2010 and against Dallas in 2011. I guess nobody—not even Kobe nor LeBron—is immune from mental lapses, from anxiety.

I’m bringing this up here because LeBron’s fear of failure, his concerted efforts to combat that fear, and his transformation into one of the greatest basketball players of all time crystalize for me the importance of the two most important words I learned at the Center: “It’s possible.” When you read that, you’re probably cringing. You probably think I mean “It’s possible,” as in Kevin Garnett’s “Anything is possible,” as in “Don’t give up on your dreams because anything is possible if you work hard.” That’s not at all what I mean. I hope those things are true too—they’re probably not—but that is not what I mean.

I don’t mean it’s possible that you will achieve everything you want to achieve. I mean it’s possible that you will achieve none of it. It’s possible that you will fail completely, in everything you attempt. It’s possible that you will make an embarrassing mistake at work and lose the respect of your peers, become an office punch line, or worse, get fired. It’s possible that you will never attain financial security. It’s possible that you will never be satisfied in your relationships, that you’re a disappointment sexually, that your crush across the way really doesn’t like you and never will. It’s possible that your partner will cheat on you or that there will be another terrorist attack tomorrow.

If you’re a basketball player, it’s possible that you will lose to the Dallas Mavericks in the NBA Finals and that seemingly the entire country will revel in your shortcomings. It’s possible.

This is the most significant lesson I learned at the Center. It’s the key to overcoming obsessions, to resisting compulsions, and to reengaging in what you value in your life. The most succinct explanation I can offer is this: the crux of OCD is fearing a specific outcome (obsession) and doing whatever you possibly can to avoid or prevent that outcome (compulsion) to the point where your actions are entirely irrational, are accomplishing absolutely nothing, and are disrupting—if not outright debilitating—your daily functioning. The treatment for this is called an exposure—specifically, it’s called ERP (Exposure and Response Prevention)—which we spent four hours doing every day at the Center. Basically, you directly expose yourself to whatever it is that is terrifying you and sit with it for as long as it takes for your anxiety to drop and for your mind to realize that your compulsions are unnecessary.

For example, Patient X—let’s call her Zahra—has an obsession that she will impulsively stab herself with a knife one day. To prevent this, her compulsions are to remove every knife from her apartment, to repeatedly reassure herself that she is not in danger, and to avoid sharp objects at all cost. This cost, unfortunately, is rather significant, as she frequently has panic attacks while being around knives at restaurants and while visiting other friends’ apartments; she’s afraid to be left alone at night because she might find some way to hurt herself; and she is almost constantly tormented by mental images of stabbings, blood, and blades. The treatment for this—her exposure—would likely be to practice holding knives in her hands. Perhaps for only a few minutes at first, but then for longer stretches of time. First small, blunt knives, then large, sharper ones. First with a coach, then alone. This will be traumatic work for Zahra. She will feel as if her life is in danger throughout. But over time, she will habituate to this trigger, and her mind will gradually accept that she does not need to engage in her avoidance compulsions. She’ll move her knives back into her apartment. She’ll use them when appropriate. She’ll stop reassuring herself that she’s safe. But she’ll never know for sure, will she? All it takes is one action, one moment. She’ll always be uncertain.

Living with that uncertainty is the key to overcoming OCD, encapsulated by the phrase “It’s possible.” If you can sit with that doubt, you can live your life and engage in what you value. If you can’t, you’re going to be doing compulsions for multiple hours a day, and you will suffer immensely for it.

The specifics of my own symptoms would require too many words to explain here. OCD affects me in dozens of different ways, and I always hesitate to oversimplify it for fear of shortchanging an important human experience. One of my obsessions that is simple enough to explain, though, one that manifests itself through a variety of different compulsions, is that my loved ones are about to die this minute and that I’ll either be the cause of their death, will fail to prevent it, or will simply be destroyed by it. Just like with Zahra, you might want to reassure me that my friend isn’t dead just because she hasn’t responded to my text for 15 seconds. You would tell me I don’t need to call the police or check in with her colleagues or have a panic attack or spend two hours imagining and mapping out all the explanations for why she hasn’t responded. You would tell me that everything is okay. But at the Center, you learn that reassurance is a four-letter word. It’s instinctual for any halfway compassionate person to tell someone who is irrationally worried about some unlikely outcome that the outcome is unlikely, to point out that things will almost certainly be just fine and that there’s no need to worry. This is what everyone tells their anxious friends, but it’s counter-productive for the OCD mind. It may seem inexcusably cruel at the time, but telling someone with OCD that their obsessions might actually come true is far more helpful for them because it forces them to sit with uncertainty.

“Maybe you will contract a disease from that toilet seat. Maybe your friends are talking about you. Maybe you did just start a fire. It’s possible. Who knows, really?” Sitting with that doubt is the key to everything.

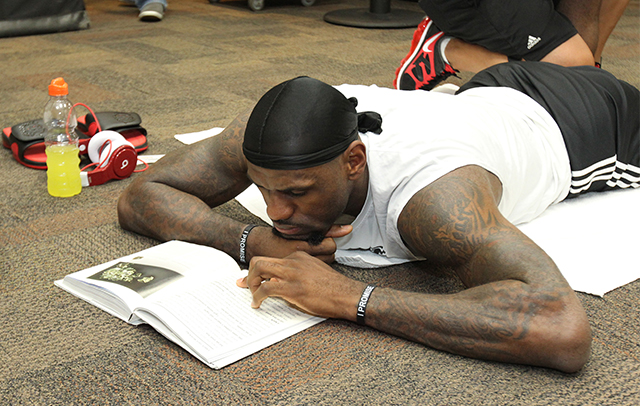

Like anyone who has struggled with anxiety, which is almost everyone, LeBron feared an outcome. He feared failure. By his own admission, the uncertainty of the game’s outcome affected his play. To combat this, he made efforts to be more mindful, to live in the present instead of dreading the future, and he did it publicly. He started meditating on the Miami sidelines before tipoff. He swore off social media during the playoffs. He read books in the locker room before playoff games to quiet his mind. Michael Wilbon reported that a close friend of LeBron’s said, “It went from pleasurable for him to being therapeutic. You can get too wired before a game, and this definitely helps him drain that, helps him avoid the anxiety of the playoffs.” His teammates were stretching and talking to coaches, and there was LeBron, reading The Hunger Games on national television before the Eastern Conference Finals.

These were powerful images for people like me who utilize similar mindfulness skills every day to deal with crippling anxiety. It’s not something you expect to see on such a grand stage, from such a popular athlete. People turn to sports for all kinds of reasons. One of them is that a team’s season or an athlete’s career is one long parable for what normal non-athletes struggle with every day. Watching people work hard, collaborate, recover from injuries, try, fail, try again, fail again, fail better, and maybe eventually succeed edifies us to believe that we can do the same in our own lives, and even if we can’t, it makes us think it’s worth trying. Has any recent superstar athlete embodied this paradigm better than LeBron? He failed against Dallas, as all of us have at one point or another. But he slowly became a more mindful person, he made concrete efforts to stop focusing on the outcome, to stop fearing failure, to enjoy the process, and now he’s likely going down as one of the two greatest basketball players of all time, if not the greatest, alongside the fearless MJ.

This is inspiring stuff for anyone struggling with anything, but for people struggling with mental illness, especially an illness like OCD that is driven by near-paralyzing anxiety, LeBron’s journey to the top is unrivaled in its sports magnitude and its analogous application to our struggles. I have lived with OCD since I was 13 and can remember the roots of it taking hold in my mind far earlier than that, but learning to sit with uncertainty has begun to loosen OCD’s hold over me, ever so slightly. It’s possible that things will all work out well. It’s possible that they will all go to hell. Nobody really knows. And that’s okay. My doctors taught me that every day, and LeBron reinforced it every other night. We may not be able to run or dunk or fly like he can, and maybe we’re dealing with struggles that are far more complicated and serious and significant than a basketball game, but the parable holds weight. The approach can be the same. I guess we can all be Kings, is the larger point.

Long may we reign.

—

Vinay Krishnan is an attorney and a writer living in Brooklyn. Follow him @vinayrkrishnan.

To learn more about OCD, visit iocdf.org.

Images via NBAE/Getty