When I was a 24-year-old pastor, I was booted from leading an East Tennessee congregation in 1983 because I committed an act of blasphemy: I sought to ordain three women as deacons in a male-dominated Baptist church. More than 30 years later, I can’t seem to shake the charge of blasphemy as I defy the roundball gods and their mortal mouthpieces and argue that Kobe Bean Bryant is the greatest basketball player this globe has seen. For many hardcourt acolytes, such a declaration surely calls for me to repent of my sin and get baptized in the River Jordan. Even Larry “The Hick From French Lick” Bird, after his Celtics barely weathered the relentless downpour of 63 points by His Airness in a 1986 double-overtime Playoff game, declared that, “It’s just God disguised as Michael Jordan.” Jerry West’s silhouette may form the NBA’s official logo, but Jordan’s body of work is where many believe that hoops greatness paused most memorably to lace up its sneakers.

It’s impossible, and unnecessary, to deny Jordan’s God-like status. Jordan has no peer as the greatest commercial and cultural force the game has seen. But saying that Jordan is the greatest basketball player ever—ball dribbled on floor, ball in hoop, footwork, shot selection, discipline, work ethic and the like—well, that’s a different argument altogether. Despite the golden consensus that hugs Jordan’s head like a halo, the insistence that he’s the GOAT has always been an article of faith, an exercise in groupthink, grading on a curve, or an act of rebellious deconstruction in shaping the facts to fit one’s interpretation. Think about it: Bill Russell damn near doubled Jordan’s ring count, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar scored the most points ever, won more regular season MVPs and collected just as many titles. Why aren’t they universally proclaimed the greatest? The stubborn orthodoxy of Jordan’s singular greatness appears ripe for a paradigm shift. As the idea’s originator, Thomas Kuhn, argued, a paradigm is a theory about how the world operates, and when disconfirming evidence steals our confidence in that theory, we’ve got a crisis on our hands, which leads us, if we’re open and honest, to shift paradigms and adopt a more compelling explanation about what’s true. Here’s the truth: In most of the categories that matter, Kobe is equally as good as Jordan, and in some cases, even better.

“You’ve never seen anyone with the footwork [Kobe] has, the athleticism, the shooting ability,” Kevin Durant tells me. “Being able to shoot the three off the dribble, off the catch and shoot, off the post. You’ve never seen that many skills in one person, outside of Michael Jordan. Of course, he doesn’t have six finals MVPs, or six titles, but skill for skill he’s unmatched.”

It’s that six-six-six spell of perfection that bedevils those who would dispute Jordan’s supremacy: six trips to the Finals, six rings, six Finals MVPs, a lyrical and morally neat rounding out of the terms of unrivaled greatness. But what seems at the time as a necessary proclamation of superiority may later be exposed as arbitrary, or at the very least, an assertion colored by preferences that are neither logical nor objective. There is, for instance, Russell’s ethical arc of 11 Championships when he was a controversial center of attention—an outspoken black man leading one of the whitest teams in all of sport to the throne of grace by first forcing it to hear the groans of race. Russell’s Celtics more than doubled Jordan’s three-peat by winning eight straight Championship trophies and 11 chips in 13 years. Russell also equaled Jordan’s five regular season MVPs. From the beginning there’s been a nod to a mystical, je ne sais quoi quality when asserting Jordan’s unchallengeable greatness; there is the appeal to something intangible, something that transcends statistics. Let’s call it analytics in service of a broader, more satisfying sense of athletic completeness, an omni-competence that reflects a level of mastery that is not only physical but spiritual and emotional as well. Beyond shooting percentages, Championship hardware and MVPs there is basketball intelligence, killer instinct, herculean work ethic, a nimble intuitiveness about the game’s improvised elegance, all of which Jordan had, and Kobe, too, though, arguably, in greater abundance.

Of course we must battle the hackneyed notion that Kobe could never be as great as Jordan because Mike first embodied the kind of greatness they together share, and therefore, Kobe was a carbon copy of the original. Depends on what you mean by original: Jordan was a chip off of some blocks that came before him.

“I never held true to that argument,” says former All-Star, Warriors coach and current ESPN on ABC analyst Mark Jackson. “And the fact of the matter is that there was Dr. J before Jordan. Jordan will tell you that. We don’t say there was no way Jordan could be better than Dr. J. because he emulated him. It makes no sense. At the end of the day, Kobe has put himself in the discussion because of his greatness, how hard he’s worked. You have to be that good. Larry Holmes isn’t Ali, not because he didn’t work his tail off. He’s just not Ali because he wasn’t as great as him. Let’s give Kobe his credit.”

Lakers’ fan and rapper/actor/director Ice Cube does just that. “Dr. J got something to say about Jordan’s game, too—Elgin Baylor, and the Ice Man [George Gervin] and all those great dudes who showed style, grace and creativity on the court. And power and strength.”

While it may be a tribute to Jordan’s sheer genius and originality that he eclipses those who came before him, we may cut a better and simpler explanation with Ockham’s razor: just as John F. Kennedy maximized his advantages over Richard Nixon on television in their pioneering debates—the medium was relatively new and Kennedy’s telegenic appeal made him seem a more natural fit with the American public than the twitchy, self-conscious Nixon—so Jordan made the most of a birth order he couldn’t bribe, but which he could certainly exploit: the players most like him in the past largely peaked before the NBA became a powerhouse league full of stars with household names. The NBA was then plagued by low ratings, tape delays for Championship games and a turbulent transition of the Association from a white man’s fantasy league to a black man’s dreamscape. All of these factors—plus the fact that the players Jordan cribbed from were past their primes when they got some shine on TV—conspired against Jordan’s predecessors and thrust him into the spotlight while obscuring just how much of his game was borrowed from the greats who came before him. Kobe cribbed from Jordan the way Jordan cribbed from Dr. J and David Thompson. It takes nothing away from Bryant that his work resembles the master who came before him.

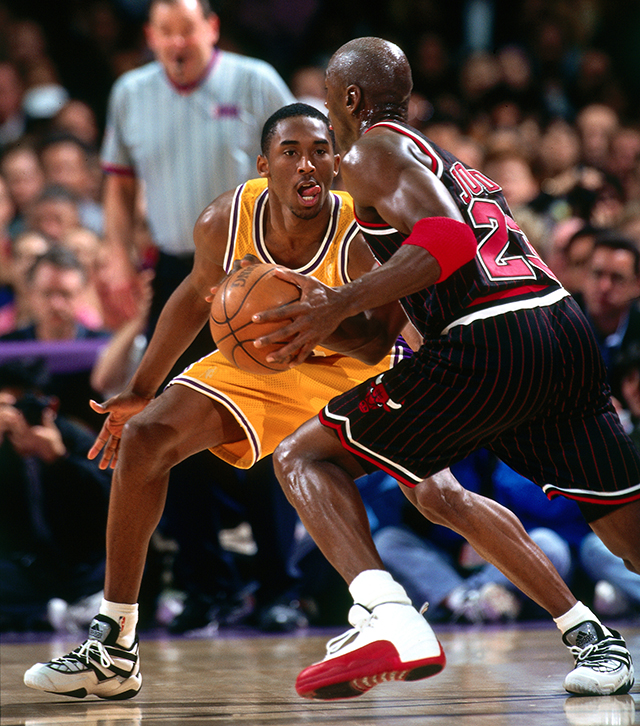

Jordan, for his part, nods to Kobe’s brilliance, and by strong inference his own, when he says he could beat everyone in today’s game in one-on-one matchups except Kobe, “because he steals all my moves.”

“I agree with him,” Kobe tells me with a laugh. “I’m a big historian, and I understand a lot of Michael’s game is built off of how Jerry West played: pull-up shots, the stop-and-gos and things of that sort. So it’s interesting—if you follow the lineage of players it’s easy to see who they watched and who they learned from. Because those games are really the same, tactically. The only thing that changes is the person that’s executing them.”

Brian Shaw, who first faced Kobe on a court in Italy when Bryant was a pre-teen, and who later played with, and then helped to coach, Kobe, argues that Kobe and Jordan are nearly dead even and that MJ gets the slightest of nods for what is essentially a forensic matter: Jordan has six rings, Kobe five. Still, interestingly, complicatedly, almost contradictorily, he argues that because Kobe benefitted from seeing Jordan play, he may actually be a better player. “I think that Kobe may have exceeded Michael in terms of just development of overall game,” Shaw says. That’s getting closer to my argument: Kobe’s level of skill is simply unmatched in the history of the game, even by Jordan. Kobe took even more time than Jordan to develop his game; he was monastic and monomaniacal about mastering the game.

“Jordan was obsessed, but Jordan did other things,” Jackson says. “Jordan played golf. Jordan played cards. Jordan went out. He played baseball. With Kobe Bryant, it’s been strictly basketball 24/7. His crazed work ethic is historic. We’ve seen nothing like it: how hard he’s worked and how he has chased perfection throughout his life.”

Kobe’s former Laker teammate and now Hall of Famer Shaquille O’Neal can attest to that. “He has a tremendous willpower and tremendous focus,” O’Neal tells me. “Much more than I ever did. Put it this way: I probably had 30 parties a year. Kobe never went to any of them. He’s like, ‘Naw, man, I’m cool.’ We come back at 2, 3 [a.m.], we see Kobe and his trainer coming up, and we say, ‘Damn. This dude working out at 3 in the morning?’ So he had a crazy, crazy, crazy work ethic.”

When I ask Kobe about his magnificent obsession, he’s downright abstract and cerebral. “I think it’s a constant curiosity,” he says. “It’s constantly trying to figure out why things happen, why things work. Having the strength to honestly assess things and honestly assess yourself, see what you did wrong and what you could do better. And what you did great. And just being really honest with yourself. And then from that point you can then move forward to try to be better.”

Jordan has been rightly given credit for getting better year after year and working on his game, adding weapons to his arsenal, including a killer fade-away jumper that he could shoot over taller defenders. Kobe did the same thing. At the dawn of his career, Jordan was a determined yet relatively limited scorer, relying heavily on his dunk, a solid low-post game, a reasonable mid-range game, though he didn’t have much of a three-point game. Kobe’s arsenal from the start was far more complete and well rounded. Shaw argues that Bryant really had no weakness. Shaw played against Jordan but says he never saw anyone have the ability to quickly absorb new information and alter his game to compensate for even a perceived deficiency as Kobe had. Shaw recalls Kobe being told by a reporter from Seattle that his daughter thought Bryant was the game’s greatest player, but that he didn’t have a three-point game. She thought that was his only weakness. Shaw remembers the day clearly. “And he said to the reporter: ‘Oh, is that right?’ So after the reporters left he stayed in the gym and he just shot three after three after three after three. And the next night when we played the SuperSonics, he set the three-point record. He hit 12 threes.”

As good as Jordan’s footwork was, Kobe’s is even better, the product of a boyhood spent in Italy where soccer was dominant and where Kobe honed his skills. His yen for perfection started early. Listen: “Once I started playing soccer, I watched it every day. I watched basketball, too. Then I started making the connection between the two of them. So certain things that I may see [Diego] Maradona do, I’d come out on the court and try to do a basketball version of it. So it was conscious on my part, trying to migrate [one sport to the other], to bring together both of those disciplines.”

Like Jordan, Kobe’s incredible discipline and work ethic led him to practice like he played. For Kobe, practice was the game; he was shooting an endless string of jumpers long before anyone deigned to come to the gym to work on their craft. Kobe always came earlier and stayed later than anyone else, busying himself in honing his skills. He not only tried everything he tried in a game in practice first, but he tried it at the actual speed of the game.

“As a coach you try to teach young players, and even your kids when they play, that it doesn’t do you any good to practice something at a lesser speed than what you’re going to be faced with doing it in a game,” Shaw says. “And, over and over again, not only with the ball but, more importantly, without a ball, Kobe would practice his footwork and practice his moves at game speed.”

If Kobe had an even greater desire than Jordan to master the game in itself, some have argued that the game Kobe mastered was a kinder and gentler—read: softer—version than Jordan faced because of the change in defensive rules. The infamous Jordan Rules that allowed the superstar to be knocked about—and which prodded him to bulk up in his offseasons—are said to reflect a rougher time in the NBA, a time when Kobe might not have fared as well because he couldn’t handle the hand check or the tougher measure of play. But it’s a safe bet that Kobe could handle the pressure just fine, thank you. “With guys like Michael Jordan and Kobe Bryant, the rules don’t matter,” says Mark Jackson. “So I wouldn’t dumb down their greatness and give any credit to rules.”

What’s not often spoken of is how, during Jordan’s era, a team couldn’t play zone the way it can now—keeping a player on the other side of the floor, basically playing two defenders on an opponent—thus encouraging duels and shootouts between gifted players in a one-on-one matchup. If one player was on the left side, say, everyone else had to be on the right side. With such one-on-one coverage, highly gifted shooters enjoyed a field day—in fact, they enjoyed many such days. In today’s game, two or three people can flock to the ball and force a player to pass it. Or a player can go to the other side, double-team an opponent, sit in the paint for two-and-a-half seconds and clear out on the same side of a player’s isolation. In Jordan’s era, if a player even looked like he was coming on the other side of the court, he was was nabbed with a defensive violation. Thus one-on-one was king, playing to the strengths of a gunslinger like Jordan—and for those who were even more gifted scorers, like Kobe, that would likely have yielded quite a scorer’s payday.

“If you gave any one of us guys that can score at a high level [such] one-on-one coverage, it’s to our advantage every time,” Durant says to me. “We don’t talk about that [in comparing Kobe and Jordan]. We only talk about hand checking and physicality. So imagine if the best scorers in our game today—Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, Steph Curry, Russell Westbrook, guys like that—played all one-on-one, all the time. Imagine the points they would score. Imagine the averages we would see.”

It must be said, too, that Jordan never faced the athletic competition that Kobe had to face. “Once he was in his prime they started to breed the 6-8 super-athletic shooting guard, and he was out there holding his own against everybody,” Durant says. Jordan was a bit more muscular than Bryant, and MJ’s direct competition at his position wasn’t as tall, talented or athletic. “I look at the type of athlete that Kobe faced,” Ice Cube tells me. “All of them were Jordan-like in some ways as far as athleticism [goes] in the League; [the competition for Kobe] was on a whole ’nother level. So Jordan was [one of] the most athletic of his time, and the most dominating. I don’t know if Kobe was, but he still got the [same] results.”

The more athletic competition forced Kobe to make far more complicated shots than Jordan, a difference that even Phil Jackson admits. Kobe has routinely made circus shots with hands in his face, bodies strewn in his path, forcing him to launch inconceivably difficult shots that swished the net many more times than it seemed possible. “So I’ve had to figure out how to shoot over double teams and shoot pull ups,” Kobe says. “And defenses were able to disguise their traps and their schemes a lot better. So I think out of necessity I’ve had to figure out how to hit those tough shots over those defenses.” The ballyhooed defensive rules that supposedly made Jordan the tougher player didn’t force him to make the tougher shots.

And Kobe was every bit the killer as Jordan, using similar willpower to impose his desire and design on the game. “It didn’t matter whether you were his teammate, whether you were his opponent, whether you were his coach,” Shaw says. “If he sensed any weakness in you at all, he’s going to try to rip your throat out.”

Cleveland Cavaliers star guard Kyrie Irving recognized that killer instinct in Kobe when he mercilessly swatted away one of his idol’s shots in the year he retired. “Even [Kobe’s] block on Jordan in Jordan’s final year—everybody criticized him for it, but that’s what makes Kobe Kobe,” Irving says to me. “Jordan would’ve done the same thing if he was playing against Julius Erving. It’s just that competitive drive that we all try to emulate.”

That willpower of course led Jordan to some highly iconic moments, none more dramatic than his famous flu game in the 1997 Finals against the Utah Jazz when Jordan proved his physical courage and valiance by playing a Championship game while his body was wracked and depleted. It was indeed a remarkable sight seeing his comrade Scottie Pippen walk him from the court, exhausted and spent, everything left on the floor in a critical victory. Still, less sexy, but far more remarkable, is how Kobe played the balance of a season with a broken finger. For Kobe, it was everyday necessity, not heroism, valor or physical courage. “I basically played with a soft cast for the rest of the [’09-10] season. And we had to face the Celtics in the Finals, which is a physical team, and they went after that finger every chance they got. So I just had to figure it out. I always looked at it as if, ‘History is not going to remember the fact that I had a broken finger as to why we didn’t win a Championship.’ So there’s no sense in complaining and whining about it. I just need to figure out how to do it.” Figure it out he did. He moved the ball more to the center of his palm and started using the middle finger and the ring finger, instead of the index finger, to follow through on his release.

“Well, he had the highest pain threshold of anybody I’ve been around,” Shaw says. “I’ve seen him come down where he would roll his ankle all the way to the floor, and he’d be writhing in pain. But he’d just sit on the floor for a minute and then he would tell himself eventually that it didn’t hurt and he was OK. And he might take a play off and go over to the bench and kind of work his ankle around. And then he’d get back up and come in the game.” Most remarkable is how Kobe ruptured his Achilles while being fouled and then shot his two free throws before walking under his own power off the court. “I can remember coaching the game where he tore his Achilles,” Mark Jackson says. “And I’m sitting there and telling my team, ‘Don’t go for the okey-doke. You know, he’s fine, he’s going to try to take over this game,’ not aware of the fact that he was seriously hurt. Because I watched him time and time again in those situations tell his body: not now.”

Beyond the finger and Achilles, however, Kobe was tested in a far more trying psychological fashion when he faced sexual assault charges in Colorado that damaged his reputation for a time. Bryant is reflective about that period and philosophical about how he played through the turmoil and pain.

“Basketball has always been an escape,” Kobe says. “It’s always been a sanctuary. It’s taking all those emotions that I’ve had within me and using basketball as the outlet for them. It’s always been there for me since I was a kid. It’s always been the place where I can release these emotions, these pent-up frustrations. So to me it wasn’t a matter of having a strong focus and being tough minded, and all sort of stuff. It was more therapeutic.”

It is nearly inconceivable that Bryant, while facing the possibility of losing his freedom for the rest of his life, would often travel by private plane from court appearances earlier in the day to play in a game that night. Less than 11 hours after he pled not guilty to sexual assault charges in Colorado, Bryant flew to Los Angeles to appear in a Playoff game against the San Antonio Spurs where he scored 42 points. “Do you know the mindset that it takes to allow that to wear on you physically and mentally and still go out and do your job?” Jackson asks. In response to Kobe’s “sanctuary” argument, Jackson says, “It’s fine to say that’s where you express yourself. And there are guys that would feel the same way, but nobody would’ve done it like he did. I mean, he went out and still performed at an all-time great level in the process of going through it. And I would bet my last dollar that only two guys in the history of the game could’ve done it, and that’s Michael and Kobe. And one had the platform to do it, so we know he did it.”

What he also did was win titles with, comparatively speaking, less help than Jordan, a point that veteran guard Brandon Jennings made in 2014 on social media when he proclaimed that Kobe is “the greatest ever” and tweeted that “Kobe had Shaq. MJ had Pippen, Dennis [Rodman], Ron Harper, Horace Grant, Steve Kerr, Toni Kukoc, John Paxson, BJ Armstrong.”

Players like Rick Fox, Glen Rice, Derek Fisher, Robert Horry and Brian Shaw himself might quibble with Jennings in suggesting that Kobe was exclusively dependent on Shaq, but his point about the pedigree of help Jordan had stands—and, we might add, the consistency of Jordan’s “supporting cast” and his coach, while Kobe had more coaches and players to contend with as he contended for his chips. Many folk contend that, unlike Kobe, Jordan never had a dominant center like Shaq to depend on, to go inside-out, to rely on to pound and patrol the paint. That’s true, but Jordan also never had to defer to another ego as strong as his, to another player as dominant as he was. Jennings also tweeted that “MJ never won without Pippen. Kobe won 2 rings without another great on his team. Kobe is the Goat.”

The social medium on which Jennings expressed his views about Kobe’s greatness is one that Kobe has carefully migrated to, expressing his opinions, and unlike Jordan, even speaking a bit about social issues.

“Well, I think it’s about speaking your mind,” Kobe says. “A big misunderstanding is that when an athlete speaks his mind the perception is, ‘Oh, the athlete’s right,’ or ‘The athlete’s wrong.’ I think that’s not good. The important thing about having a stage, or having a platform from which to speak, is [that] you create conversation. And hopefully the conversation that’s created is a healthy one that advances the particular topic forward versus the silliness of, ‘Ah, I don’t agree, he’s an idiot.’ ‘No, you’re an idiot; he’s right.’ That’s really sandbox, immature dialogue. So for us as athletes, and any of us who have a voice, when we speak up about a particular issue, or a particular cause, there are people out there who disagree that an intelligent conversation can be had [despite there being] a disagreement. But we must have the idea of advancing the cause forward, versus winning an argument.”

When I ask Bryant about the toxic political environment in which the country is embroiled with figures like presidential nominee Donald Trump all the rage, he is considered and thoughtful, discrete even, but not neutral in his assessment of the fallout from our political folly.

“I think you have, obviously, different opinions,” he says. “This is the beauty of living in such a democratic culture. Everybody’s entitled to their own opinion. Everybody has a platform to have their voice heard. Especially with social media and all of these outlets you have. And I think it sparks conversation. Now the question to ask is, does it spark a healthy conversation, or does it create friction to the point of negativity? I believe our leader should be a person that creates healthy dialogue versus creating a negative friction.”

Bryant is also fond of entertainers like Kendrick Lamar and Beyoncé finding a social register in their artistry, risking controversy to make important political interventions. As for Lamar’s racially charged Grammy appearance this year, Bryant had nothing but praise. “I love what Kendrick Lamar’s doing. I thought his performance was outstanding. I think he has an idea of how his music can be greater and live longer than simply being music. I think he’s communicating that voice in a grand way.” Bryant is equally supportive of Knowles, who caused quite a stir with her Super Bowl halftime performance of her song “Formation” that pleads for a cease in police killings of unarmed blacks and revels in the undervalued luxuries of black self-love. “Beyoncé’s sparking intelligent conversation. And it’s our job as artists to create those conversations. And now us, as a culture, it’s our responsibility to take these conversations and move them forward. What she did was great. I thought it was beautiful.”

Also beautiful, though little known or remarked on, is how Kobe, behind the scenes of his withering focus and killer competitive urge, is also a deeply caring man. As Shaw argues, figures like Magic and Jordan are more loved by the public, while Kobe “has been more demonized than them. But there’s a side of him that’s very, very generous that people don’t know.” I witnessed Bryant’s generosity up close: a woman from another country contacted me on Twitter because she knew Bryant followed me, and because her brother had battled a serious illness and she wanted nothing more than to have his favorite player wish her brother a happy birthday. When I relayed her wishes to Bryant, he not only obliged, but he did so in spectacular fashion: instead of complying with her wish to have a simple video made on a cell phone, Bryant sent a professionally produced video to the young man wishing him continued recovery and a bright future. It was a moving, compassionate gesture. When I ask Kobe how he’d like to be remembered, he replied, “As a person that left no stone unturned and did everything possible to try to reach his full potential. And years from now, hopefully, what I’ve done [will] inspire others to be able to approach their craft and their lives much the same way.”

Amen. Speaking of which, the Christian church, my Christian church, still has backwards ways when it comes to gender, but we’ve also made significant strides in addressing justice for women and other minorities. So what was once deemed blasphemous and worthy of expulsion may now be considered prophetic. Maybe my words on Kobe as the globe’s greatest basketball player ever will one day soon enjoy a similar fate.

—

Michael Eric Dyson is a University Professor of Sociology at Georgetown University and an award-winning writer whose work has been featured in the Op-Ed Section of the The New York Times, The New Republic and in the best-seller section of your local bookstore—where you’ll find his most recent work, The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America. Follow him on Twitter @MichaelEDyson.

Photos via Getty Images

—

RELATED: SLAM Presents KOBE is Coming Soon!