“There was no moment.”

Jerry Stackhouse sits behind the scorer’s table in a gym in Mississauga, Ontario, reflecting on how he got here. From his seat, he watches CJ Leslie, a forward with the Toronto Raptors D-League affiliate, Raptors 905, shoot jumpers from the left elbow. Practice ended 15 minutes ago and Leslie is one of the last players still out on the court. Now it’s the extra work, the shots that fall outside the scope of the cameras and headlines and social media. Now it’s the grind.

“I just kind of transitioned toward it,” Stackhouse says, shifting forward in his chair. “If you’d asked me in the first 10 years of my career, did I see myself being a coach afterward? I mean, nah. Probably, at the time, I would have had the mindset of a player. I would have thought I was going to play forever.”

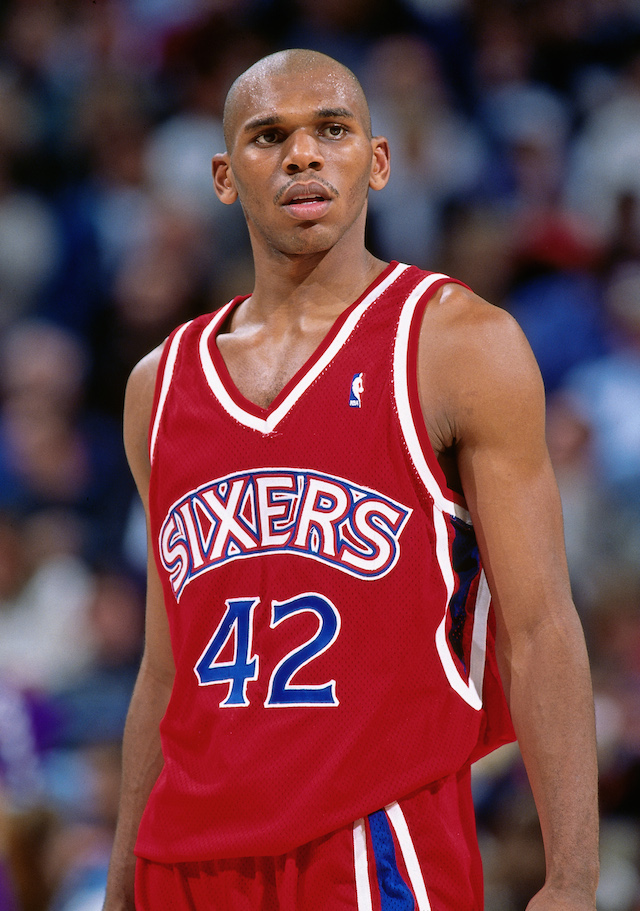

In 1995, in a draft held in Toronto, the Philadelphia 76ers selected Stackhouse third overall out of the University of North Carolina. Expectations swelled. He came from the same school, was the same size, played the same position, as Michael Jordan. He was the next great hope, a high-scoring, high-flying phenom. Stackhouse joined a team that lost its star—Charles Barkley demanded a trade after eight seasons in Philly—and as a rookie, he led the Sixers in scoring, averaging nearly 20 points a game. He scored most of those points in the same way: soaring to the basket like he was trying to get up and out of the gym, above the noise, beyond the hype and expectations and demands that can sink a young player.

In the end, Stackhouse would play for eight teams over 18 seasons. His game, and what was asked of him, evolved at each stop, from aerial assaults to dependable jumpers and veteran leadership. But the hustle was always there, and so was the chip on his shoulder. Stackhouse waited his turn and constantly modified his game, but always played with an edge. It worked. He became a two-time All-Star, reached the Finals and, in 2001, he would have led the League in scoring if it weren’t for the brilliance of Allen Iverson, whom Stackhouse used to wake up for practice during their brief run together in Philadelphia.

Stackhouse saw it all, from being the star and calling the shots, to redefining his game just to get on the court. He became a mentor, drawing from his playing experience and what he learned from a long line of legendary coaches—Dean Smith, Doug Collins, Rick Carlisle. When he played in Dallas for Avery Johnson, who logged 16 seasons in the League, that’s when he began to consider coaching for himself. It wasn’t a sudden realization, there was no prophetic moment, but over time he got there and now that he’s made the leap, he’s sure of it.

“You get a real gratification out of seeing guys get better,” Stack says. “Watching them break down processes and bad habits, and building new, good basketball habits. That’s the beautiful thing about it for me, just seeing them get it. Seeing that light bulb flash on.”

The sound of a ball hitting hardwood fills the gym now, the brief rhythm of a dribble before Leslie launches another shot skyward. Stackhouse’s eyes follow the arc of the ball. It’s been a little more than three years since he last played, but as the leather falls through the mesh, he finishes the thought.

“I feel like this is what I’m supposed to be doing.”

In the winter, it can be difficult to read the banners that billow outside Mississauga’s Hershey Centre, the arena the 905 call home. Some days, snow can cake onto the fabric, rendering everything white, or blizzards can roar and blind, or the wind can reduce anything pliable to an unreadable writhe. But on calm days, the words are clear: The Road To The Six Starts Here.

In the D-League, the goal is impermanence. Players, trainers, coaches, referees. Everyone is trying to move up, trying to move on. The line between the NBA and the D-League is both impossibly thin and endlessly vast. And beyond the requisite talent, it often takes the right timing, opportunity, and a little bit of luck to bridge that gap. Not everyone will reach the next level. Not everyone gets this close, either.

In the basement coaches’ office, there’s a Dean Smith quote painted along the top of the wall of white brick with exposed pipes: “A leader’s job is to develop committed followers.” Just below that are the whiteboards, the gathering space for Stackhouse and his staff, where he stands or sits, in silence or with music blasting, and figures out his next move, like a mathematician working through an equation. This is where he plies his craft now.

The setting isn’t new, but the role has changed. That’s one of Stackhouse’s strengths. Whatever the situation, he’s seen it before. He knows how to relate, the demands of the job, the mental and physical grind. That’s important in the D-League, where nothing is guaranteed and everything happens quickly. Stackhouse is unaffected by the uncertainty. He’s lived through it, found success in it.

At practice, he’s animated, bouncing on his toes, pacing the sidelines, a whiteboard grasped in one hand, a basketball tucked under his other arm. He shouts instructions, demonstrates what he wants to see. Sometimes, during scrimmages, he leans back when a play unfolds and draws in a deep breath that fills his chest, then he holds it until the play is over, like he’s trying to slow down the moment. He’s invested in this, that much is clear.

“Not everyone figures it out early,” he says. “I never figured it out early. There are guys here that have been overlooked, I’ve been there. I know there are guys on NBA teams that are no better than the guys I’ve got on this team, 1 through 15. They would be on somebody’s team right now but for whatever reason, it didn’t happen.”

That could change at any minute. Last season 32 players were called up. There’s no telling when that window will open, or how long it will be until it inevitably closes. That’s why “stay ready” is a message Stackhouse preaches. He brings up Leslie. “For whatever reason, he’s got all the talent, all the tools, he just hasn’t been able to put it together,” Stack says. “Now he’s one of the last guys to leave the gym. What does that translate to production-wise? He’s probably been our best player.”

Stackhouse is a demanding coach, he says, but balanced. He knows not to push too hard without first building relationships, until it’s understood that everyone is in this together. Time helps with that, but so do extracurricular activities. Stackhouse organizes team outings, bowling, cards, movies. In November he hosted Thanksgiving at his house. Over the smoke of the barbecue, he talked basketball, but beyond basketball, too. “I know how important that is,” he says. “We do things to keep the vibe light, but whenever we’re between lines and we need to get better they know I’m serious and they know I demand a lot.”

And if he doesn’t like what he sees, he doesn’t hesitate to get back on the court. Stackhouse—who once soared for a reverse dunk with so much power and grace that on the replay, Dick Vitale frantically bellowed “Look at this, America!” like a historic moment was unfolding—well, he still has some life in those legs.

“It’s still in me man. I hope I never lose that.”

And the trash talk? That’s still there, too.

“I tell ’em, they won’t see nobody in the D-League like me,” he laughs. “They hate that.”

The next day, the 905 play a game at the Air Canada Centre, the Raptors’ home, and one of two games they will play in the NBA arena this season. An hour before tip-off, Stackhouse speaks with reporters in a media scrum in the basement. Behind him, playing on a large TV screen, is a montage of his career. He watches it for a moment and then laughs. “Where’d they find that?” he says. “That microfilm or something?”

He’s loose, but the same can’t be said for his players. It’s early in the morning, just after 10, but it feels like any other primetime game. There are more than 15,000 people in the stands, the largest single-game attendance in D-League history, and when the players come off the court, in that brief moment after warm-ups and before tip off, they snake through the tunnel and the cameras and lights follow them, and in that instant they are as close to the dream as they can be. That’s a nerve-racking thing.

Nerves are temporary, though, and in the second quarter, there’s a play that stands out. Leslie fakes a jumper from outside the elbow, then takes two spring-coiled steps, cradles the ball like a running back and launches himself into the air. On the sideline, Stackhouse watches with his arms pinned to his sides, his chin lifted, eyes wide. For a moment Leslie hangs there and everything seems to stop, but when he flushes the ball through and then swings forward on the rim, his momentum carrying him, everything roars back into focus.

Soon after, Stackhouse calls a timeout. He high-fives his players as they stream into the huddle and then grabs his whiteboard and takes a seat. His team surrounding him, he draws up a play, waving his hands, shouting, trying to overcome the noise. He tells the players where he wants them to be and then, as they lean in closer to hear this next part, he shows them how to get there.

Photos via Getty Images