Antoine Walker is 72 years old now, fully half a lifetime removed from his 2012 retirement from basketball and a half-century beyond his selection as the sixth overall pick of the 1996 NBA Draft. But as he picks up the NBA game ball, spinning it in his hands, and toes the four-point line in Boston’s Red Auerbach Garden, you can still see the athlete beneath the veneer of years. He eyes up the basket 28 feet away and lets fly.

Walker is part of this story because the story doesn’t exist without him. Well, maybe it does, but he’s an integral part of it nevertheless. Back in the early 2000s, during one of his three All-Star media appearances, Walker was asked why he shot so many threes. “Because there are no fours,” he famously responded. At the time, Walker was attempting somewhere around seven or eight threes a night, and Hall of Famer Steph Curry hadn’t even started high school yet. His words would become prophecy.

Four-pointers are normal enough now, all an entire generation knows. They started as a BIG3 (remember the BIG3?) gimmick shot in 2017—kind of like how the three-pointer originated in the ABA before debuting in the NBA—and then became a league-recognized shot over a decade later in 2028. Curry, then in his final season at age 40, already the all-time three-point leader, found his familiar launching spot now worth an additional point. He not only surpassed Jamal Crawford’s four-point record (Crawford having retired five years earlier at 43), he passed LeBron James to become the NBA’s all-time leading scorer and won the inaugural Four-Point Shootout at All-Star Weekend, narrowly edging Trae Young and LeBron James Jr.

Twenty years later, the four is commonplace. It’s important to remember that, while the introduction of the three-point line in 1979 changed the game so dramatically that it took nearly 40 years for a full-on revolution to happen, the four-point line was embraced quickly. In the first year of the NBA three-point line, Clippers guard Brian Taylor led the league in threes, hitting 90 in 78 games. That paltry number would stand as the single-season record for three seasons, until Darrell Griffith broke it with 91 in 1984. It would be nine years before anyone hit 100 in a season. That was Danny Ainge, who hit 148 in 1988. By 2018, a full 12 players hit 200 threes in a season, led by MVP James Harden’s 265. Two seasons earlier, Curry had set an NBA record with 402, taking more than 11 attempts a game.

By that time the floor had spread so much, the players become so long and athletic, that the next logical step was to spread the floor itself. But the matter of history and records (and expensive courtside seating) made such a change difficult. There had to be a better reason. So in the process of adding the four-point line, the NBA expanded the court for the first time ever—from 94×50 to 104×55—allowing for not only a full 23’9” three-point arc, but 25-foot corner fours. Keeping the 24-second and eight-second clocks meant things sped up anyway.

The four-point line was instituted in college that year as well—at the 23’9” distance of the NBA three-point line—but seeing that the college game was already primarily a three-or-dunk proposition, it didn’t affect the gameplay as much as it did the scoring. Records, like Troy State’s 258-point game and Pistol Pete Maravich’s 44.2 ppg average, seemed primed to fall.

But a funny thing happened on the way to four-point Nirvana. Spreading the floor that much further and teams regularly launching from 25 feet out led to something else—a big man renaissance. With more room to operate and plenty of rebounds to corral, other records fell instead. Amir Cousins pulled down 50 rebounds in a 2030 game for the Kentucky Wildcats, shattering the post-’73 record of 37. And seven-footer Shaquille Lewis averaged 45 ppg in his lone season at LSU before being drafted first overall by the Golden State Warriors in 2031.

In the NBA, there was more room for bigs to operate too, but the four-point shot mostly opened things up for the shooters. After all, they’d been waiting for this opportunity for a long time. Stephen Curry and his Golden State Warriors 25-footered their way to six titles through the teens and early ’20s, and the Philadelphia 76ers even went so far as to put a four-point line down on their practice court’s floor in 2018, a full decade before the line became a reality for the rest of the NBA.

When it did, all of a sudden those coaches who complained that their young charges were just launching deep threes trying to be like Steph decided that this wasn’t such a bad thing after all. The Rockets and the Warriors led the way while some teams—like the mid-range centric Knicks, led by their 25th coach of the millennium—more or less pretended the four-point line wasn’t there at all. It also put a premium on shooters. Word was that the Spurs actually called up 52-year-old Hall of Famer Ray Allen before the start of the ’28-29 season to see whether he’d give it one more shot. Allen, well on his way to qualifying for the senior PGA tour, passed.

Zaire Wade, then 26, quickly adapted to the deeper shot, finishing second in fours to Curry and averaging a career-high 34.6 ppg, besting Hall of Fame father Dwyane’s best single season average of 30.2. The elder Wade was proud, yes, but also prideful: “When we played we didn’t have fours,” Dwyane said. “If we did, you bet your ass I would have averaged 35.” Wade the younger, knowing his pops averaged under 30 percent from 23’9” for his career, wisely kept his mouth shut.

That first year had its moments. A four-point lead could now be erased by a single shot, and early on coaches failed to realize this—or fouled when they didn’t need to. Then there was the matter of Donte DiVincenzo, the No. 17 pick out of Villanova in 2018 who had bounced around the league before landing in Minnesota. With the help of assistant coach Jamal Crawford, he became the league’s first five-point specialist, able to draw contact and still hit from (very) deep. Double-digit deficits could be made up in two trips down the floor. What was once just a saying became absolute truth: No lead was safe.

Bigs got theirs a little later, as teams got used to looking for deeper looks. Offenses spread, and vets like Shareef O’Neal and Bol Bol got busy. Teams with shooters looked to team them with agile bigs like Bol and O’Neal who could chase down long rebounds and either reset the offense or finish strong. O’Neal, a free agent pickup for Lakers GM Kobe Bryant on a mid-level deal of six years, $300 million, nearly doubled his scoring and rebounding averages to 35 points and 18 boards per between 2028 and 2030. He turned out to be a bargain.

Bol Bol manned the middle for the Golden State Warriors—a team that had previously employed his 7-7 dad as the league’s most unorthodox three-point specialist. They’d previously established a dynasty thanks to the three, one that just would have been that much more dominant had Curry’s deep threes counted as fours. They replicated their success in the ’20s with a balanced attack, fours from LaMelo Ball—who they’d signed away from the rival Lakers after hiring father LaVar as a special assistant to GM Bob Myers—and Bol’s flawless inside game.

But just as teams adapted to the Warriors run-and-gun (and gun) style of the ’10s, teams adapted to their four-and-the-floor style of the ’20s. Celtics coach Antoine Walker encouraged his team to launch everything—damn the shot clock—while the Miami Heat, led by LeBron James Jr and Zaire Wade, used a more planned-out style of attack backed with an in-your-shorts defense. The Chicago Bulls, meanwhile, were still rebuilding. And the Knicks—nobody knew what the Knicks were doing.

Which more or less brings us to the current day. No one has eclipsed Curry’s record of 402 threes in a season, and it’s likely no one ever will. Not now. Perhaps, though, someone will one day top it with combined threes and fours, as players edge ever closer to the mark. The Houston Rockets backcourt of Zion Wade and Chris Paul II came close, as did Timberwolves guard DJ Rose. At 36, Rose will get another shot at it. And of course there will be new challengers to the throne, like rookies-to-be Trey Iverson and Smoothie Antetokounmpo.

Has the four-point shot been good for basketball? Is that even a valid question to ask? As long as there has been basketball, there have been those who’ve bemoaned each and every innovation, from the jump shot to the slam dunk to the three-pointer. And no amount of 3D GIF highlights beamed through those haters’ iHomes will change that. Which, quite honestly, is their problem. The game changes, but the game lives on.

There are fans today who don’t remember a game without a four-point line, and that’s fine. There are others—not many, but some—who still remember the game before threes. Michael Jordan, 85 years old now, still thinks he was better than anyone who ever played, four-point line or no. Seven-time champion and six-time MVP LeBron James feels the same way at 63.

Then there’s someone like Walker, who lord knows would have jacked up fours by the dozen had they existed when he played. But that was a long time ago, and today Walker’s range isn’t what it used to be. His shot is more of a heave, and his first attempt clangs off the front of the rim. He beckons to a ballboy, who feeds him another. He rotates the ball, centering commissioner Joel Embiid’s signature under his fingers, and lets fly again.

*Swish*

Walker looks over and ruefully shakes his head. He doesn’t say anything. Which is fine. The meaning is clear just the same.

—

This is a fictional story written from a fictional future. Please keep that in mind.

—

Russ Bengtson is a freelance writer. He tweets @RussBengtson.

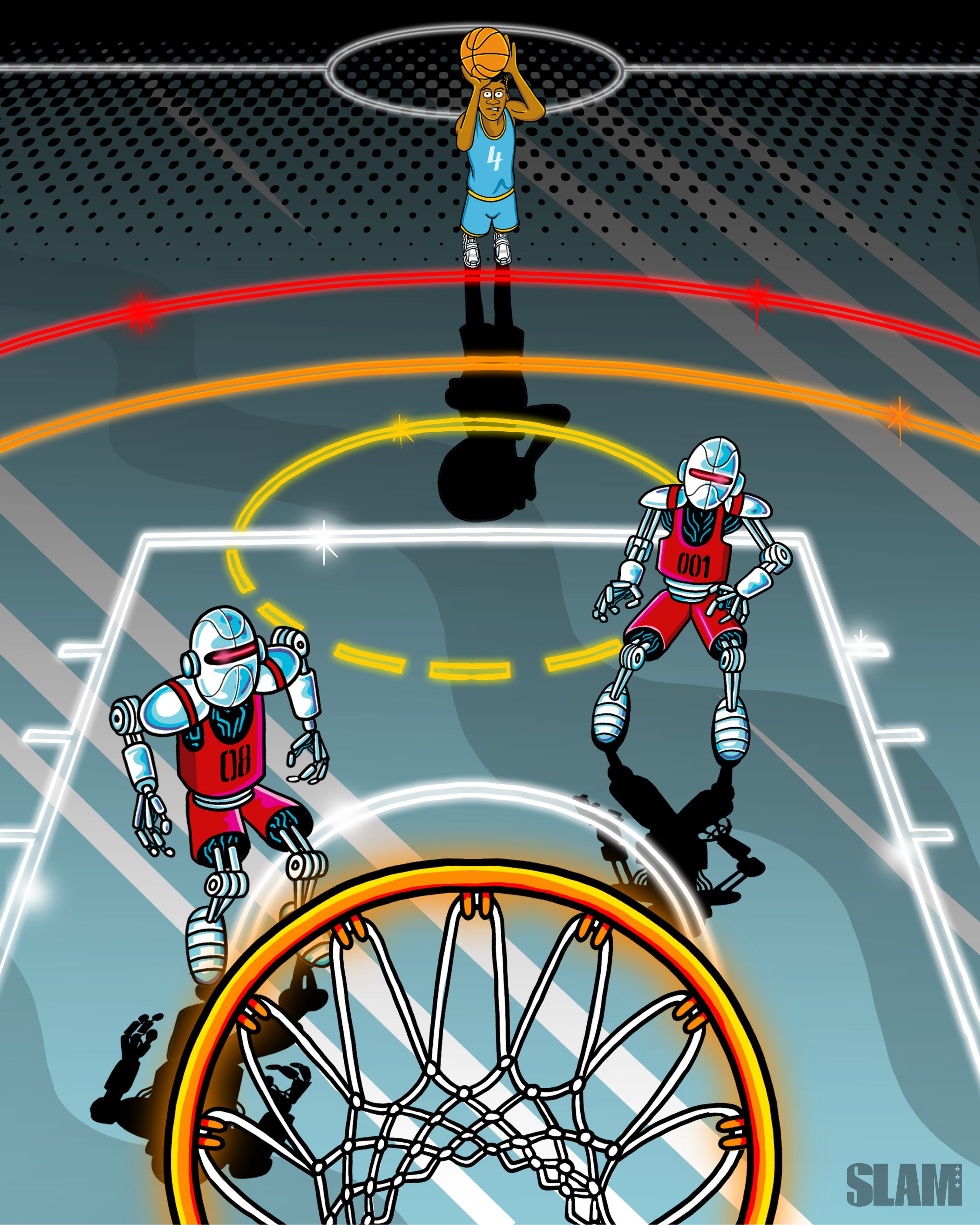

Illustration by Mark Ward.