Savage Mode — SLAM 213 Cover Story on Devin Booker

The Beautiful Struggle — SLAM 213 Cover Story on CJ McCollum

—

December 12, 2012. The Golden State Warriors were visiting downtown Miami for a showdown with the Heat. LeBron James was fresh off winning his first NBA championship and, at the age of 27, unquestionably the greatest player in the world. This is back when the Warriors were an insignificant foe. They were quietly a fun team to watch for basketball diehards, but they had three rookies in their rotation and were about to face basketball royalty.

This would be a daunting task for the Warriors, but one rookie sent a message to James, one that would become an omen that the Warriors were game for the challenge. The underdog Dubs were up 65-61 midway through the third quarter when Draymond Green checked back in. This time, his assignment was LeBron.

The first possession, Green goaded James into settling for a 19-footer that he missed. About a minute later, Green came up with a steal off a James pass. With the Warriors’ lead up to 5 late in the third quarter, James went to the post. It was time to get serious, finish the quarter strong and put the Warriors away. He drew a foul on Green.

As James walked to the free-throw line, Green, the 6-7 second-round pick out of Michigan State, the tweener off the bench whose NBA career started six weeks earlier, was jawing at the best player in the game.

“I’m not gonna back down,” Green recalls, seated on the side of a court at the Warriors practice facility in downtown Oakland during a late October afternoon. “I had a couple of successful possessions and I started talking junk. He took me to the post next play. LeBron hits a layup and goes, ‘You’re too little!’ And I’m like, ‘Too little? You know who you’re talking to?’ That was always my mindset.”

Green and James continued to exchange barbs as the game came down to the wire. With 11.4 seconds remaining and the score tied at 95, the Warriors called a timeout and drew up a play designed to get the ball into the hands of either Stephen Curry or Klay Thompson. The Heat knew it, judging by the way they overplayed the Splash Bros. Green was waiting to set a screen so Thompson could emerge on the left wing for a look. Ray Allen followed Thompson around the screen and Shane Battier, defending Green, cheated up the lane to cut off the passing lane to Thompson. Green, displaying his basketball IQ, slipped the screen while Allen and Battier were diverted and cut to the rim, waving his arms to show point guard Jarett Jack he was open. Green jumped to catch Jack’s pass and put it in before landing. Ballgame.

“I told myself I’m about to walk off with so much swag and I just start running with my arms up like a little kid, like I just won a championship,” Green says. “Having that type of moment against LeBron as a rookie, a guy I watched for years growing up, to have that moment was huge for me in my career.”

For Green, it was evidence that he could hang with the NBA elite, an idea that was once far-fetched to the rest of the League.

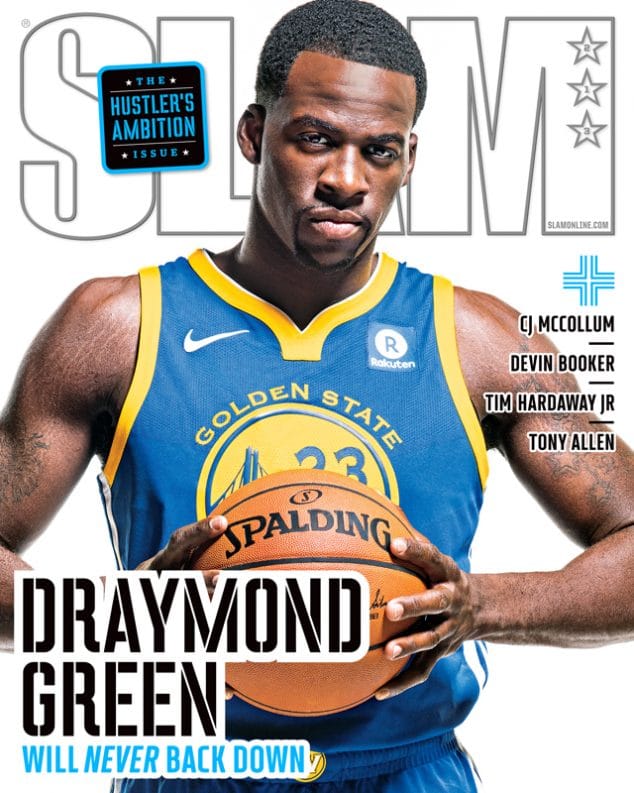

That you are reading this, a SLAM Magazine cover story on Green, illustrates his drive to shatter the narrative about him. Green doesn’t just want to win—he wants his due respect. He wants his victory topped with high regard. He wants a legacy.

It’s a consuming drive, one that shuns reality and morphs perspectives. It gnaws at a man’s soul. Few can understand. Which is why before the Warriors won their first title, Green reached out to one of the few who did: Kobe Bryant.

Bryant, renowned for his ambition, connected with Green’s desire. A mentorship was born.

“He was curious, just like I was when I came into the league,” Bryant told SLAM via email. “So he called me up and asked me questions about the game, about leadership, about winning. And it was very similar to how I approached the game coming into the League. So because of that, I feel a connection to him.”

That’s why Green making it to this level is quite the story. It’s not the typical proved-everybody-wrong tale that so many athletes have. Green didn’t simply discredit a prediction from a whole bunch of basketball analysts; he forced them to change the way they think. He proved he could do what they said he couldn’t, but he also did what they didn’t think was possible. Green has become an unconventional NBA superstar, a household name who hasn’t sniffed a 20 ppg average. And he did it by talking about it before being about it, by calling his shot before drilling it.

Scouting reports said he was too small. He couldn’t shoot. He didn’t have a true position.

Taking down James, knocking off the Heat, this was Green giving the middle finger to all the scouts who doubted his potential. This was the beginning of him vindicating himself against all the general managers who passed on him, causing him to fall to the second round of the 2012 Draft despite winning NABC National Player of the Year in his senior season at Michigan State.

Green maintains this chip on his shoulder because at every level he’s been doubted. He says when he was in middle school, he was written off for not being the best prospect in his hometown of Saginaw, MI. He got to high school, started every varsity game as a sophomore and all he heard about was how he could be a low Division I player. Instead, he landed at powerhouse Michigan State.

“It pissed me off,” Green says, smashing his fist on top of the table in front of him. “National Player of the Year in college and I go in the second round? That doesn’t even add up. It was one of those things where I was like, OK, I’ll prove them wrong again. But then it’s also like a slap in the face. How much more do I need to prove?”

Even after his rookie year, there was doubt about how long he would last in the League.

Green remembers a list that was released at the end of that season naming a number of players and what they needed to do in order to remain on an NBA squad. His name was right at the top.

On a color-coated shot chart to indicate the player’s efficiency from certain areas on the court, Green was considered “cold” from every spot. The consensus was that he was decent on defense, but if he didn’t improve his offense, his days in the NBA were numbered.

“It was mind-boggling to me because I came into the NBA as more of an offensive player,” Green says. “I didn’t really defend in college—I played great help-side defense, but that was about it. I can make a shot, but I’m not a shooter. I just had to figure out ways to incorporate myself more within the offense and do more to create more value. But there was always that doubt of what I couldn’t do as opposed to what I could do.”

The adversity frustrated Green, but it was no foreign concept. Green had dealt with doubters from the first time he laced up his Nikes and roamed the streets of Saginaw in search of pick-up games.

Green constantly went up against players who were older than him. As a first-grader, he played on the third and fourth grade team at Longstreet Elementary School. When he got a little older, he’d hit up the Civitan Recreation Center right across the street from his house and bug the older guys to let him play with them. The rec center featured a court that sat on top of a 10-foot high stage, usually reserved for the adults. Green, still a kid at the time, refused to get off the court.

“One of the guys pushed me off the stage. Another guy would hit me in the head with a basketball. That’s just how it was in our neighborhood.”

Running home and telling his mom what happened was not an option. Mary Babers-Green didn’t raise no chump.

In her eyes, the grown men picking on the younger Green were just toughening him up.

It was up to Draymond to handle his own business. Green would keep pushing back until they eventually let him get in on the action. It was those games at The Civ where Green developed his physicality. And the art of verbal warfare. Before Green could ever imagine talking trash to the likes of LeBron, he learned it at The Civ.

“That’s where all the trash talking comes from,” he says. “You pick that up as a kid and that’s part of the player that I am today. It’s getting inside someone’s head. A lot of people can’t handle it.”

When Green was not battling it out with grown men at The Civ, he was playing for The Family, an AAU team in Detroit. He developed a strong friendship with fellow teammate Jordan Dumars, son of two-time NBA champ Joe Dumars.

Joe was President and General Manager of the Detroit Pistons at the time, and Green’s relationship with Jordan afforded him the opportunity to attend Pistons games and hang out in the locker room at the Palace of Auburn Hills. Green even frequented the homes of Pistons stars such as Rasheed Wallace and Rip Hamilton. But there was one Pistons player in particular Green really gravitated toward: Ben Wallace.

“I still got this family picture we took and I got on a huge afro,” Green says. “I remember days wearing that afro thinking I was Ben Wallace. He was locking the entire NBA up. Even Shaq.”

Wallace took Green under his wing, showing him the ropes and serving as a mentor as he continued to advance in his basketball career. It makes sense that out of all the Pistons, Wallace was the one to build the strongest bond with Green. After all, the two have some eerily similar paths to greatness.

Like Green, Wallace was considered undersized for his position. Scouts felt there was no way a 6-9 center could hang with the big dogs in the NBA, so he went undrafted out of Virginia Union before signing with the Washington Bullets in 1996.

“We both got it out the mud,” Green says. “Nobody gave us a shot in hell.”

It took a few years, but after signing with the Pistons in 2000, Wallace went on a brilliant six-year run that saw him rack up four Defensive Player of the Year awards and serve as a key piece in bringing Detroit an NBA title in 2004.

Wallace blazed his own path, showing that height would not deter him from shutting down the game’s elite skyscraping centers. It’s a path Green has followed and is looking to extend.

Green made it no secret that one of his goals was to follow in Wallace’s footsteps and win Defensive Player of the Year. After narrowly losing out to Kawhi Leonard for a couple of years, Green finally got over the hump and captured the award last season.

Green received the DPOY trophy before a preseason game on September 30. But instead of a regular Warriors staffer presenting it, Green was surprised by Wallace, whom the Warriors flew out from Michigan.

“I see huge similarities between the two of us,” Wallace says over the phone from his home in Michigan. “From a kid at 10 years old, he would ask me, ‘What do I need to do to improve my game?’ He’s one of those guys that never stops studying the game. He’s always looking for knowledge. A true student of the game.”

Draymond also has that “cerebral assassin” DNA that made Kobe so great. He wants more rings. He wants more Defensive Player of the Year awards. He’s willing to do whatever it takes to go down as a legend.

“Whatever you need, he’ll plug in and provide,” Bryant says. “If you need rebounding, he’ll do that, if you need scoring, he’ll do that. If you need defending, he’ll do that. He has a tremendous amount of versatility. You can put him anywhere on the court and he’ll provide for you.”

Against all odds, Green has not only made it in the NBA—he is flourishing.

“Now the goal that I can never reach until I’m done playing, and it’ll push me until the end of my career, is I want to make it to the Hall of Fame,” he says.

Two-time NBA champ. Two-time All-Star. Olympic Gold medalist. Defensive Player of the Year. In his prime at 27, Green’s Hall of Fame résumé is steadily growing as he looks to secure his legacy. Green would never admit to actually enjoying the doubt, but it’s providing the fuel for one hell of a career.

Related

Savage Mode — SLAM 213 Cover Story on Devin Booker

The Beautiful Struggle — SLAM 213 Cover Story on CJ McCollum

—

Martin Gallegos is a writer based in the Bay Area. Follow him on Twitter @MartinJGallegos.

Portraits by Atiba Jefferson

—

SLAM 213 is on sale next week! Pick it up at newsstands and bookstores nationwide.