New Yorkers who dream of their Knicks winning an NBA title don’t die, they multiply. Bringing Phil Jackson on to run the team has reinvigorated NYC hoops fans, who swear their former player will help lead them back to their glory days—hard as those may be to remember. Though those years predate a lot of today’s basketball fans, the Knicks did have an excellent run in the early ’70s, winning two titles in a four-year span and cementing the Big Apple as one of the basketball capitals of America.

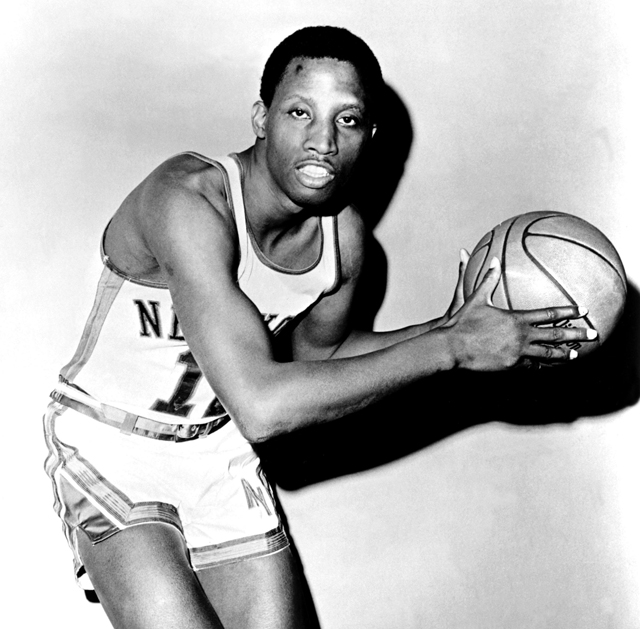

As one of Jackson’s teammates back then, Dick Barnett was a key contributor to those glory days. The No. 4 pick in the 1959 NBA Draft out of Tennessee A&I (now Tennessee State), Barnett was selected by the Syracuse Nationals and then played for the L.A. Lakers and Knicks. He was a deft scorer who made the ’68 All-Star Team and put numbers on the board everywhere he played. Barnett, aka “Fall Back Baby,” who retired with a 14-year career average of 15.8 points per game, sat down with SLAM recently to discuss those Knicks teams, why the Knicks haven’t won a title since and why furthering his education became a lifelong mission.

SLAM: What is your story of getting into basketball?

Dick Barnett: I grew up poor in a segregated Gary, IN. My dad worked in the steel mills and we lived under de facto segregation. Basketball happened by happenstance. I was playing around on the outside courts, the playground and then figured out I was pretty good. I was recruited to play at Roosevelt High School and then started my high school career.

SLAM: How did you end up at Tennessee State for college, and was going there your first time in the South?

DB: Yes. I had to get indoctrinated into the conditions of southern living. Living under segregation, racial animus, the reign of the Ku Klux Klan. We’re talking about George Wallace and all of the things that were going on at the time. That was a part of living in Nashville from 1955 to 1959 when I left.

SLAM: How was it playing for Hall of Fame coach John McClendon?

DB: Playing for Coach McClendon was great. He showed us unconditional love and spent time honing our skills. I felt that I was an accomplished athlete and he let me know that my abilities were as good as anyone else in America. He was an understated, non-demonstrative person, but very emphatic that we nurture our abilities. Passing and pressure defense would really express the greatness of our teams and that’s what we exemplified. He told us to be very careful too, of course. The system we were involved in made our accomplishments more impressive than UCLA’s or anyone else. We were the first team to win three national tournaments in an age when racial backlash was rampant. What we accomplished was very significant.

SLAM: How nerve-racking was traveling through the South?

DB: We all had to be smart. We understood that in the racist system we were involved in, every young and old black man’s life was in jeopardy. We had to be careful.

SLAM: Did your love for education blossom at Tennessee State?

DB: I wasn’t a very good student at Tennessee State and I actually left without a degree. I obviously was a tremendous basketball player and focused on what I needed to do to become a Draft choice in the NBA. At the time, that was the most important thing to me. At the time I didn’t understand that academics and athletics could peacefully and productively co-exist. I really didn’t get it back then. That understanding came later on with maturity.

SLAM: You were drafted by Syracuse and then later played for the Lakers. What were the highlights of playing in L.A.?

DB: Obviously it was a new situation. I got to play with Jerry West and Elgin Baylor, two all-time greats. I had a successful run for three years there, until I was traded to New York. Obviously I had more success with the Knickerbockers than anywhere else.

SLAM: Is it true that while in L.A. you got the nickname “Fall Back Baby” from legendary Laker announcer Chick Hearn?

DB: No, I got that on the playgrounds. When I shot my release, I told everybody to go back on defense because it was going in. Just fall back, baby.

SLAM: What’s the first thing you learned when you got to New York?

DB: Playing against the Knicks you become acclimated to the rivalry and the city, so obviously I knew New York was very serious. It was a very exciting place to be and they had a very knowledgeable fan base about basketball, football, whatever. I felt like my skills would fit in very nicely.

SLAM: That Knicks team had a lot of talent on it. Did you immediately know how you were going to contribute?

DB: Well, when I got there, the Knicks weren’t very good. But they made some major trades—they got Dave DeBusschere from Detroit and kind of established playing Willis [Reed] then and [Walt] Frazier, all those things. It took a few years before we became a juggernaut to be reckoned with.

SLAM: How would you describe those Knicks teams? What words come to mind?

DB: Those teams were very intelligent, very knowledgeable. We knew how to play basketball and we used our intelligence and basketball acumen together over four or five years. We played teams that were more athletic and used our intelligence against them. We were athletic, too, and maybe weren’t the most athletic team, but we were the smartest. We played together and we were a hard team to beat.

SLAM: How was the offense set up?

DB: We had a lot of guys who could play, a lot of guys who could score, so we didn’t really have one guy. Whoever was open would get the ball and we understood the weakness of other teams. It was very comprehensive.

SLAM: Off court, were you close with any of your Knicks teammates?

DB: Not particularly. Each guy went his own way. Guys had their own plans on what they wanted to do. I started getting into education in my free time.

SLAM: What was the social climate of New York like in your playing days? Better than the rest of the country?

DB: There was the black and civil rights movement and that was happening across the States and in New York, too. You had Martin Luther King and he emerged and Malcolm X, too. America was experiencing a political convergence. We were at the apex at the end of the ’60s and beginning of the ’70s when we won our first Championship. New York was experiencing the knowledge of what was going on at the time in the same way as everyone else.

SLAM: How excited were you when the team won that first title?

DB: That was just a basketball thing, so yes I was, but it was different for me. An NBA career is three years old or less and I played 14 years. I played in every state in the union. All over the world and it was all tied to sports. I was already happy, but yes, it was quite exciting. We won two Championships during this era and the Knicks haven’t won any titles since, so people have long memories of those teams.

SLAM: How important was winning a title for you personally?

DB: I’ve often been asked if winning an NBA title was the highlight of my life, and I tell people, it was great. Some guys wanted to get to the NBA, but staying in the NBA was my goal. I went from playing with ping-pong balls as a teenager to traveling to every state in the union. I’ve been to Paris, Rome, Germany, all over Africa and everywhere in the world. All because of basketball. Even though America was and is full of political contradictions, dreams really can come true here if you’re willing to work hard and be willing to sacrifice.

SLAM: What’s your take on why the Knicks haven’t won a title since?

DB: They’ve never had the right people together and you know, a lot of teams have come aboard in the NBA and players don’t play together for long amounts of time anymore.

SLAM: As your career wound down, you started to get more into education. Can you talk about what you’ve accomplished in that realm?

DB: I had an injury in 1967 and the doctor said, “You might not play any more professional basketball.” So I’m lying on the table thinking about this. I determined at that time, whether I can still play or not, that I had better get back in school, and that began my sojourn into education. I have a Master’s in Public Administration from NYU, a Master’s from Cal Poly Pomona and a doctorate from Fordham University. I’ve been a professor teaching Sports Management at St John’s and now I run a center for the study and research of athletes where I speak to kids all the time.

SLAM: When you speak with students, what do you discuss?

DB: I ask them where do they want to go from here; those are the issues that young people want to think about. History as well. Young people sometimes think history started when they began. My organization is called SportScope [learn more about it on DrDickBarnett.com.—Ed.] and I speak to kids every month. My interaction with young people is ongoing, focusing on moving toward having technology in every classroom and encouraging young people in any way.