I first met Cherokee Parks in late January, prior to a Knicks game. That was actually the third time that month I’d seen him. The first was earlier that season, before a Nets game at Barclays Center. The second was in Toronto during the G League Showcase. Parks is the kind of person who stands out in a crowd. Or, rather, he’s the kind of person you notice yourself noticing. He’s 6-foot-11, for one, though in NBA circles that doesn’t exactly make him unique. But he also has tattoos crawling up his neck and down his long, skinny arms with ink that his new business casual outfits can’t cover up. His face, long with a goatee, is the kind of face you don’t forget, especially when it belongs to a ridiculously tall white dude whose mother named him after a Native American tribe.

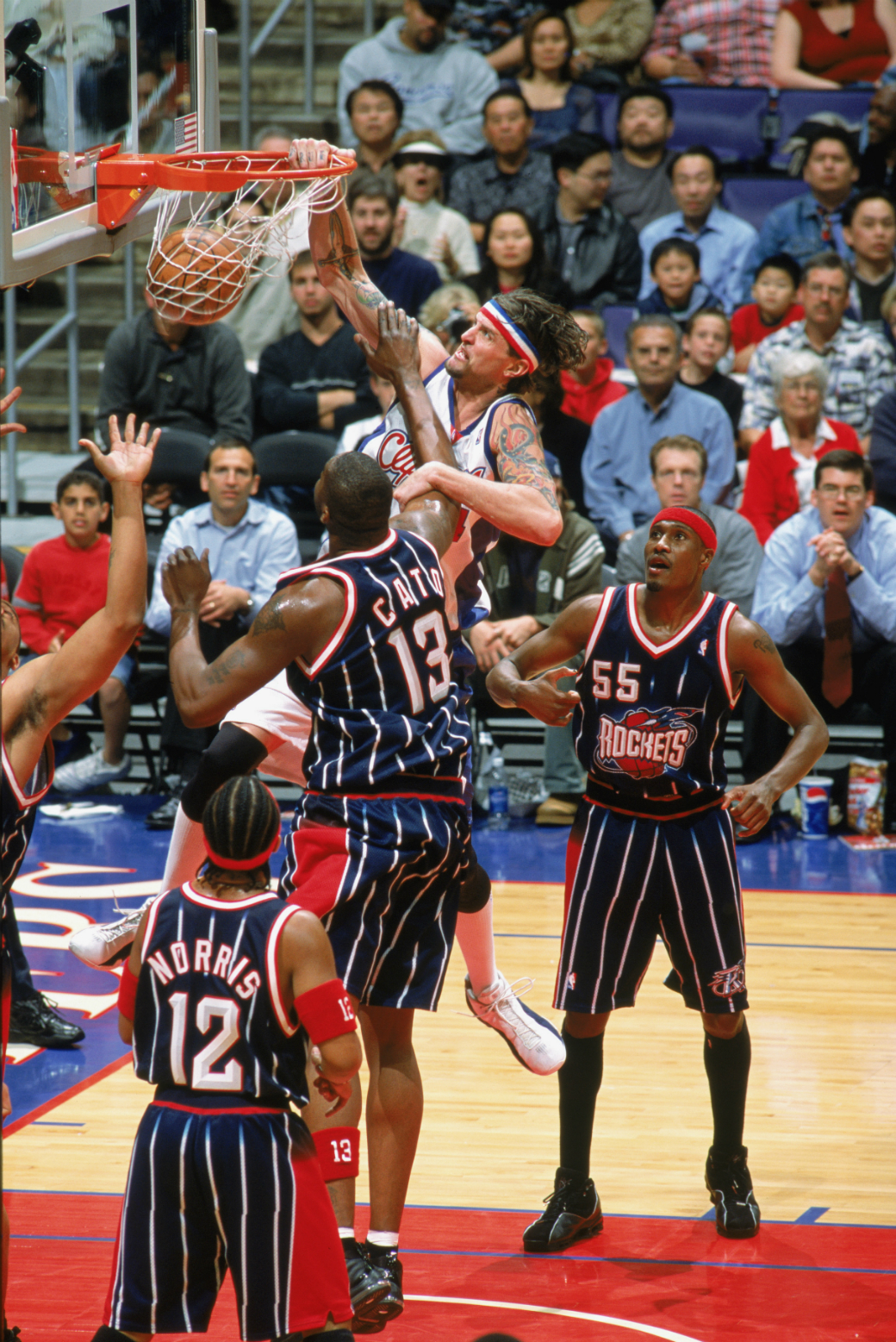

“Is that Cherokee Parks?” a longtime NBA scout asked me that night at MSG. Parks was drafted 12th overall in 1995 by the Dallas Mavericks and bounced around the League until 2004. He played his last NBA game that season, for the Golden State Warriors, and then, contrary to the way most basketball players remain connected to that life even after hanging up their uniform, he just sort of disappeared, cutting himself off from the NBA world.

Both the scout and I were curious where he’d been, and why he was suddenly popping up in random NBA arenas. So I walked over to Parks, introduced myself and asked if he’d be open to sharing his story.

About a month later I met Parks, now 45-years-old, at an East Village Starbucks, around the corner from where he now lives. “This whole area is rad,” he said. Coincidentally, he’d lived in the area—“on the same block, just two buildings down!”—the summer after getting drafted. “It’s wild, I’ve come full circle,” he said.

Parks shared the CliffNotes version of his life story: how, after a remarkably unremarkable nine-year NBA career (he averaged 4.4 points and 3.6 rebounds), he stepped away from the game to open a punk rock music bar; how around 2011 he embarked on a comeback and signed with a team in France; how two years later he underwent open heart surgery; how he’d recently linked up with an NBA internship program, officially, the Basketball Operations Associates Program, where former players like him are brought into the fold and taught the ins and outs of the NBA’s various businesses.

The job is in the NBA’s Fifth Avenue office, which is why Parks was back in New York, and why he’d been frequenting NBA games.

The program was also what Parks wanted to talk about. It introduced him to Oklahoma City Thunder general manager Sam Presti! And Boston Celtics assistant GM Mike Zarren! He’d learned about the NBA’s Collective Bargaining Agreement! He’d recently underwent some IT training! And was taught how to use Excel! And how you don’t set up meetings with colleagues by walking over to their cubicle! He’d even purchased a bunch of slacks and button-down shirts, and also pair of loafers, but he wore those out over the summer. “You don’t realize how much walking you do in New York City until you live here,” he said.

No man has ever sounded so excited about Midtown Manhattan’s stuffy office culture. That such giddiness was oozing out of one of basketball’s more renowned free spirits—remember, this is a tatted-up punk rock fanatic—was confounding.

But then talk turned to Parks’ NBA career, and whether he views it as a failure, and suddenly his excitement over his Microsoft Office conquests began to make more sense.

“Unsatisfied,” Parks said when I asked what he feels looking back. “My head was never in the right place.”

Why do you think that was?

“I was depressed a lot,” he said. “But that’s a whole ‘nother story.” It was one he was initially reluctant to tell. “I want this to be a momentum piece,” he said. Still, after some prying, he was open to sharing some details, and to explaining why the fact that he was now living on the same East Village block left him wondering if there were some sort cosmic forces at play. But also, how it didn’t matter whether that fact was happenstance or fate. This—his new life—was an opportunity Parks wasn’t going to waste.

“I get to come back and do this journey again,” he said. “I get a second chance.”

—

Parks’ childhood was far from typical.

His parents were, well, Hippie-like. His father was a musician. His mother raised her children as vegetarians and fed them mostly vegetables grown in her own garden. As for his name—they named their son Cherokee after learning that his father’s great-grandmother had been a member of the Native American tribe.

Parks’ parents divorced when he was around three years old. He spent the next seven years with his mother and two siblings bouncing between California, Colorado and Nevada, before finally settling in Huntington Beach, Calif., one of the country’s largest and most bustling seaside cities, which, perhaps, is why Parks feels that, “I thrive when there’s a program. I like when there’s an in itinerary, a syllabus.” It’s a line he used multiple times with me.

The point being: he was only craving the thing he never had.

Thanks to his height and athleticism, Parks earned a basketball scholarship to Duke. Over his four years there, while playing alongside stars like Christian Laettner and Grant Hill, he emerged as one of the country’s top basketball prospects.

“He was a super-talented big man who could post up with his back to the basket and shoot the ball from the outside,” said Juwan Howard, a former NBA All-Star and current Miami Heat assistant coach who was in the same high school class as Parks and competed against him in college and the NBA. “He was also really smart.”

Those skills propelled Parks up draft boards and into the NBA, which was great. The problem was that he entered the League during a period of heated labor strife. The 1995 draft had taken place in the midst of a lockout, which lasted from June until September, meaning Parks’ first three months as a professional basketball player were spent alone without the guidance of or instruction from an NBA organization.

This would be a theme throughout Parks’ career. The man who coveted structure never received it. He came into the NBA during a lockout, and had to deal with another one just two years later. He never spent more than two seasons with a single team. Even the team that drafted him, the Mavericks, traded him after just one season.

At one point, Parks believed that many of his NBA failures could be attributed to this chaos.

Only years later did he discover that this bouncing around was more a symptom of a greater problem.

—

He remembers the bus rides. He’d sit there, on the way to the arena, gazing out the window towards the streets of San Antonio or Boston or whatever city he happened to be in that afternoon. He’d watch the men and women walking home from the office and then think about how his work day was only just beginning.

“All I’d want to do was get off the bus and join them,” Parks said. “I wanted to join them and go home.”

These feelings began bubbling to the surface early on in his NBA career, but they were mostly dormant until the 1998-‘99 lockout. That winter, while he was in Minnesota, sadness began to wash over Parks. He doesn’t know exactly why. What he does remember is sitting on his living room couch, nowhere to be, nowhere to go, and coming to a realization.

“That I was thoroughly depressed,” Parks said.

He assumed basketball was the problem, and so he packed a bag, folded his long limbs into his 1997 GMC Yukon and drove west for 22 hours straight back to Huntington Beach. There, Parks said, “My life became complete chaos.” He declined to detail the specifics, saying instead: “The party just never stopped. Whatever you can think of recreationally, I was there, in and around it.”

That lifestyle followed him back into the NBA after the lockout. He began to develop a reputation around the League. The phrase “free spirit” comes up often when talking to his former coaches and teammates. None of them had any issues with Parks. “But we knew he liked to have a good time,” Jerry Sichting, who was an assistant coach in Minnesota while Parks played there, said. “At the core he was a good guy. But I don’t think he was totally committed to basketball.”

Which, Parks concedes, is correct. He’d spend his off days and off hours in bed, sleeping and watching TV. He’d go entire offseasons without picking up a ball, maybe jogging on a treadmill once or twice, but nothing more. He barely saw his family, including a grandmother who died from Alzheimer’s while he was in the League. When, in December 2003, then-Golden State Warriors general manager Chris Mullin called Parks into his office and informed him that he was being released, Parks was relieved, so much so that when another team called a few weeks later with a contract offer, Parks turned it down.

Basketball had been his life and he wasn’t happy with his life. Therefore, he deduced, basketball was the core of his problem.

He kept his demons to himself, talking casually with a few friends, one a Yale-trained psychologist, but never following through. Instead, Parks self-diagnosed. And self-medicated.

“It wasn’t that I was partying, “Parks said. “It was more just about escapism. But I just had no idea what I was trying to escape from.”

—

In May 2006, a little over two years after playing his final NBA game, Parks was sitting in his punk rock bar when he learned that two bands that he’d booked for a big show that evening had cancelled.

He’d worked hard on the show, spending hours promoting the event. Yet, once again, life was letting him down.

Why is this happening to me, he wondered. He was 33 at the time, and his life was crumbling. He began thumbing through a “Fritz the Cat” cartoon, a story created by Robert Crumb about the adventures of a con artist cat. He’d been reading the cartoon for a while, but something about this specific strip, in which Fritz was espousing the virtues of driving on an open road and freeing your mind from thoughts, stood out.

“At that exact moment,” Parks said, “things shifted.”

He asked himself why he couldn’t seem to get anything right, but then flipped the question into something deeper: What, exactly, was he trying to get? He played around with his thoughts for a bit, a process he described to me as a “kind of adductive, inductive, deductive reasoning thing,” all of which led him to a simple, but life-changing conclusion:

“That I,” Parks said, “was the one who didn’t get it, who was viewing things in life the wrong way.”

He still has trouble pinpointing why, exactly, the combination of some bailing bands and a talking cat cartoon triggered this come-to-Jesus moment. The best explanation he can give is that he had to undergo his own Siddhartha journey, a reference to the Hermann Hess novel about a spiritual journey of self-discovery. It’s a book he referenced multiple times in our interviews.

Parks went home that night and put a microscope to every aspect of his life. He took up journaling, and studied the dictionary so that he could better articulate his feelings. “What does irate mean?” he asked “When I say, ‘I’m irate,’ am I using it correctly?” He began underlining his favorite lines in books, which he’d lug with him whenever he moved homes. He spent more time with his family, especially with his the youngest of his three kids, a daughter who was born in 2008 and lives with him now. He’d always considered himself agnostic, but for the first time in his life he began wondering what that actually meant.

“Spiritually, there’s definitely a method to what’s going on in our lives and more to it than we can understand,” Parks said. “Why things happen—that’s not in some mystical realm. It’s available to us, but it takes a lot of dedication and introspection to get that.”

Parks spent the next few years putting his life back together. In that time, he realized that basketball had actually been one of the lone bright spots in his life, not the root of all his problems, and so he decided to attempt a comeback. He signed a contract with a team in France. He loved being back on the court and part of a group. His mind was finally in a place where he could succeed, too. This time, though, it was his body that failed him. His heart raced whenever he ran. He returned to California, where doctors diagnosed him with an aortic aneurysm. Open heart surgery fixed the problem, but his playing days had come to an end.

Still, Parks wasn’t ready to give up on a second career within the game.

“I realized I loved basketball, that I really liked the opportunities it provided and the people it introduced me to,” Parks said. He wrote down a new set of goals. One was to one day have an NBA business card with his name on it. The reason?

“I wanted to leave the game on a good note,” he said. “I didn’t the first time around. But I wanted to have a positive impact.”

—

It’s early afternoon one day in March when Parks walks into a small conference room overlooking St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue. We’re in the NBA’s main office so Parks can show me around where he works, and also share some of those details he’d initially held back.

“I just met with Brooks!” Parks tells an NBA public relations official who’s there with us. I don’t know who Brooks is but he seems to be an important person. “Brooks heads all our basketball academies oversees, he’s rarely here so you have to catch him when you can.” That’s why Parks is so excited. He’s excited about many things this afternoon: That Kiki Vandeweghe, a top NBA executive, has an office right near his; that he can now use corporate jargon like “360 approach”; that he finally got ahold of an NBA employee named Kim. I don’t catch what exactly it is that she does.

Clearly, though, Parks is ecstatic about where’s arrived in his life, and for good reason. He’s worked hard to get here. Harder than most know.

His journey back to the NBA started immediately following his surgery. He did his rehab on campus at Duke and then began reconnecting with old contacts from his playing days. He eventually got in touch with a community relations manager he knew from his days with the Clippers and said he’d be happy to do anything and everything, from appearances to handing out flyers. Through the Clippers he got in touch with Corey Maggette, who told Parks about the NBA’s internship program, where he hustled and networked and LinkedIned his way into everyone’s good will.

My interview with Parks lasts about 40 minutes. This, he says, is the first time he’s spoken this extensively about his past. “I’m getting chills just talking about this,” he adds. “This is new ground to me.” But he’s still hesitant to fully open up.

“A lot of that stuff was not something I’m proud of,” Parks said. “I’m going to make good decisions and bad decisions. But it’s memories of those decisions that I’ll always have to live with. Memories that I have to have.”

I turn off my recorder a few minutes later. Parks breathes a sigh of relief. He shows me to the office he shares with a few colleagues. He has some business cards with the NBA logo lying on his desk. His name is etched onto them.

—

Yaron Weitzman is a writer living in New York. Follow him on Twitter @YaronWeitzman.

Photos via Getty Images.