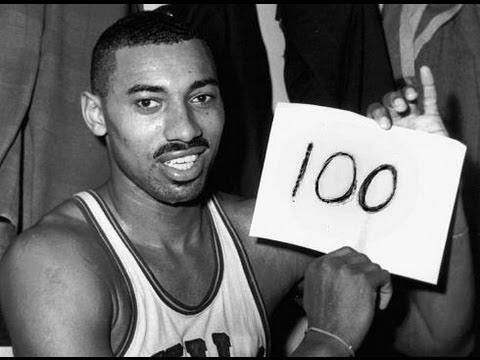

Exactly 50 years ago today, Wilt Chamblerlain completed perhaps the greatest single-game NBA feat of all time. Facing off against the New York Knicks in Hershey Sports Arena, Chamberlain—then a member of the Philadelphia Warriors—scored 100 points, a record that will continue to stand for a very long time, if not ever. (Kobe’s 81-point outburst in 2006 sits in second.) Back when SLAM hit its own century mark in ’06, Gary M. Pomerantz—who literally wrote the book on the subject—examined the incredible performance in the feature below. Enjoy.—Ed.

by Gary M. Pomerantz

It happened in a distant era, just 10 days after John Glenn orbited the earth and returned home to say, “I don’t know what you can say about a day in which you have seen four beautiful sunsets.”

The 100-point game looms as the signature moment of Chamberlain’s signature season, in which he averaged 50.4 points per game.

Among sports records, it is Everest.

It is so big that it comes with its own mountain of misinformation. Multitudes claim they were in the Hershey Sports Arena to see the Dipper hit 100. (Truth: about 4,000 people and 4,000 empty seats.) Many insist Wilt’s Philadelphia Warriors lost that night to the Knicks (Philly won, 169-147). Lord only knows how many sneer, “Yeah, Wilt scored 100 points, but he did it with 50 slam dunks.” (He used put-backs, fallaway banks, a jumper from near the top of the circle, layups off dynamic fast breaks, and you bet, some Dipper Dunks.) Some would have you believe the Knicks didn’t play hard or even care that Chamberlain scored 100 points.

Where do people get their facts?

Historian David McCullough has said, “At their core, the lessons of history are largely lessons in appreciation.” Because the game was not televised, and because no New York sportswriters bothered to attend with the Knicks’ season already lost (they would finish the year at 29-51, last in the Eastern Division), Chamberlain’s performance quickly disappeared from conversation and then from sight. Over the decades it became like a sunken galleon resting on the ocean floor, the riches in its hold waiting to be recovered.

It’s long past time to truly appreciate the Dipper’s own four beautiful sunsets that night in Hershey.

I went to see Darrall Imhoff. A Knicks golden boy in ’61-62, the 6-10 Imhoff would become known as the hapless foil of Chamberlain’s theatrics. Not fair. Imhoff fouled out that night in the middle of the fourth quarter, after playing just 20 minutes. Go easy on him.

“Show me how you played Wilt that night,” I asked, and Imhoff demonstrated. At the US Basketball Academy near Eugene, OR, where he serves as a marketing executive, Imhoff moved down low, to the left block, the Dipper’s favorite spot. I portrayed Wilt—at 5-10, a pathetic stand in—with my back to Imhoff. With his feet, he blocked me in, positioning his left foot outside of mine to keep me from turning toward the hoop. He thrust his knee into the back of my left thigh, buckling my leg.

That night, Chamberlain, ball in hand, leaned back into Imhoff with his upper torso. Fearing a giant tree about to fall on him, Imhoff recoiled. “So I did this,” Imhoff said. He jabbed his elbow into my back, a bull’s eye between the shoulder blades. It hurt.

In that fourth quarter in Hershey, the Knicks threw eight players at Chamberlain. Guards Richie Guerin, Donnie Butcher and Al Butler flashed in front. Forwards Willie Naulls, Jumpin’ Johnny Green and Imhoff crept in, stepping on the big fella. The lane was just 12 feet wide then (it was changed a few years later to the current 15, in part to limit the Dipper) and so Knick reserves Cleveland Buckner and Dave Budd moved low to the left side, Wilt’s offensive ground zero, and puffed themselves up. Not that it made any difference. That night, the Dipper bent an entire sport to his will.

As Chamberlain’s point total rose into the 80s and 90s, Guerin’s face became a red mask. The ex-Marine was furious that the Warriors were rubbing it in. Guerin thought the game had devolved into a travesty, but if so, it happened under the massive force of the Dipper’s talent. To keep the ball from Chamberlain in the game’s final minutes, the Knick guards dribbled upcourt slowly, in a Z-pattern, draining the clock. They also fouled the Warriors guards; in return, the Warriors began fouling the Knicks, a chess match played by pawns. The Knicks’ sense of dread intensified. So did the Warriors’ curiosity: they wondered how high Chamberlain’s point total might go.

In the final six minutes, the Warriors had one purpose: Get the ball to the Dipper. Forward Tom Meschery would recall it as the only time in his 10-year NBA career that he passed the ball and…watched. No cutting or moving. He simply watched the 25-year-old Dipper challenge an entire team, and take 21 shots in the fourth quarter to score the 31 points necessary to reach 100.

It was comic book superhero stuff. Until Kobe Bryant scored 81 earlier this season, the next highest total in NBA history was 73 points by Denver’s David Thompson. Michael Jordan once reached 69 points and needed overtime to get that.

When I contacted Richie Guerin more than 40 years later, he told me he didn’t want to talk about Wilt’s 100-point game.

Is Richie Guerin mad still? Let’s get this much straight, then: The Knicks played hard that night. They cared.

—

Again, David McCullough: “Indifference to history isn’t just ignorant, it’s rude. It’s a form of ingratitude.”

Here’s another lie: Chamberlain’s 100-point game didn’t mean anything. Talk about ingratitude!

Chamberlain’s 100-point performance carried rich symbolism: It was a hyperbolic announcement of the ascendancy of the black superstar in the NBA, proof that the League would be a white man’s enclave no more. It signaled loudly the pro game had changed both in the way it would be played and the men who would play it. It would be a game performed at a greater speed, from in close and above the rim. Along with Bill Russell, Elgin Baylor, Oscar Robertson and others, the Dipper changed the geometry of his sport, taking a horizontal game vertical. You had to watch him; athletically, he was that compelling. Even Red Auerbach, upon seeing the Dipper for the first time in high school, had felt compelled to stare as Chamberlain walked by. Incredible, Auerbach thought.

In 1962, the Dipper didn’t have his own shoe deal (the Warriors wore Converse high-tops) or his own posse, though he’d bought into a celebrated Harlem nightclub, the suitably renamed Big Wilt’s Smalls Paradise, and as the likes of Redd Foxx, Etta James and Cannonball Adderly performed, he moved famously through his club as if he owned all of Harlem, perhaps all of New York.

Years later, Oscar Robertson would say of the Dipper, “Almost by himself, he made the League a curiosity, made it interesting… People heard about Wilt scoring a hundred, averaging 50 a night, and they wanted to see the guy do it. I believe Wilt Chamberlain single-handedly saved the League.”

Chamberlain was fast becoming the most striking symbol of basketball’s new age of self-expression and egotism—a development slightly ahead of the overall popular culture—and his 100-point game gave him an imprimatur to continue being, boldly and unashamedly, the Dipper. (Never call him “Wilt the Stilt.” He said it reminded him of a crane standing in water. He preferred Big Dipper.)

And let us not forget the quota. In the 1950s, NBA owners abided by a quota limiting the number of African-American players to one or two per team, and in the early ’60s three or four per team. This quota was a tacit understanding that was systemic in American culture. The joke among NBA writers then: “You can start only one black player at home, two on the road, and three if you need to win.”

Chamberlain was never a civil rights activist. “I’m not crusading for anyone. I’m no Jackie Robinson,” he said in 1960. “Some persons are meant to be that way…others aren’t.” But his public passivity about race stood in contrast to the way he crushed any race-based impediments to his self-definition. He dated white women, discreetly; drove his Cadillac convertible at high speeds; and made more money than anyone else in the League ($75,000 that year). By averaging 50 points per game in ’61-62, he proved his physical superiority and made a mockery of the League, its racial quotas, and the notion that his white opponents were the best players in the world.

Then, in Hershey, he took the quota and symbolically blew it to smithereens.

Chamberlain’s scoring breakdown in Hershey: 23 points in the first quarter, 18 in the second, 28 in the third and 31 in the fourth. He made 36 of 63 field goal attempts and 28 of 32 free throws. He was a wretched free throw shooter, making barely half of nearly 12,000 free throws during his 14-year NBA career.

That was the real miracle of Hershey—Chamberlain made 88 percent of his free throws. He shot them underhanded, bending low with knees flared wide, like an adult sitting in a kindergartner’s chair, his least athletic-looking move on the court. The Knicks complained that the rims in Hershey were flimsy and, at least about this point, they were right. The circus visited Hershey each year and, as part of the act, clowns used red-varnished springboards. A few Hershey boys snuck into the arena during off-hours, bringing a basketball with them. Borrowing the clowns’ springboards, these scamps flew like mini-Dippers and slam-dunked the ball through the baskets. The boys clung to the rims—bending them—before dropping cat-like to the floor.

The Dipper surpassed 50 points in a game 45 times that season. Once he scored 73 points against the Chicago Packers’ rookie sensation, Walt Bellamy, and in a triple overtime game against the Lakers, he scored 78. In 10 games that season against the Celtics’ Bill Russell, the greatest defensive center in NBA history, the Dipper averaged nearly 40 points per game.

Chamberlain was a physical marvel, not yet muscled up from weight lifting, his body in perfect proportion: 7-1, 260. Running the floor, he covered nearly nine feet with each stride. On the break, there he was out on the right side, with guard Al Attles on the left, and the ball-handling wizard Guy Rodgers in the middle. NBA players of that era remember the way the young Dipper ran the floor and speak of it with a hushed awe and reverence. Among those precious few signature images that qualify among the defining best in NBA history—Russell’s shot block, Cousy’s dribbling, Jabbar’s sky hook, Erving’s swooping dunk, Magic’s no-look pass, Jordan’s midair majesty—is the Dipper at 25, out on the right, filling the lane.

—

Chamberlain used to say that half the planet told him they saw the game in Hershey that night. The announced crowd of 4,124 was inflated. The PA announcer, Dave Zinkoff, a genuine original, gave fans free cigars and salamis at halftime. At the moment the Dipper reached 100 points, the teammate who passed him the ball, little-used reserve center Joe Ruklick, didn’t rush to congratulate Chamberlain. Instead, he ran straight to the scorer’s table to make certain that he got credit for the famous assist. (He did.)

Don’t confuse today’s NBA with the NBA of ’61-62. Two-thirds of the players were white then, and a few set-shooters were still around, relics whose shooting form dated to Naismith’s peach baskets of the 1890s. Most big-city sports columnists then considered the NBA a stepchild to the more established college game. Stanley Woodward, sports editor of The New York Herald Tribune, once said, “I have strong reservations about the masculinity of any man who plays the game in short pants.” The NBA wasn’t truly national then, either, since it had just nine teams, and only one west of St. Louis (the Los Angeles Lakers). Crowds were so small that, as the joke went, PA announcers at NBA games first introduced the players, and then they introduced the fans.

That’s why this famous game was played in Milton Hershey’s little chocolate town in Pennsylvania Dutch country. Each NBA team played several games that season outside of the big cities in hopes of creating new fans. The sons of chocolate factory workers, pressed close to the court, swept onto it the moment Chamberlain hit 100 on a Dipper Dunk. The first to reach him, 14-year-old Kerry Ryman, shook Wilt’s hand. Then, as Chamberlain nonchalantly bounced the ball, Ryman did an impulsive, Huck Finn thing—he stole the ball and ran. He zigzagged across the court, lunged up the arena’s cement steps, burst out of the building into the cold night as his heavy breath rose like smoke. Ryman ran through the amusement park, past the bumper cars and the Ferris Wheel, over a nearby hill and on to his house on West Chocolate Avenue.

—

Nearly seven years ago, Wilt Chamberlain died of a heart attack at the age of 63, alone in bed at his Bel Air mansion known as Ursa Major. Here was a frightening prospect, for if the mighty Dipper had died, it made every NBA player of that generation vulnerable. Remarkably, among the League’s greatest 50 players from the NBA’s first half-century, Chamberlain was only the second to die; the first, dead of heart failure at 40 while playing a pickup game in 1988, was “Pistol” Pete Maravich.

The Dipper’s dominance in ’61-62 can be seen comparatively: No other NBA player ever has averaged as many as 40 points per game in a full season. The second best—Jordan’s 37.1-point average in ’86-87—would need to be pumped up by 36 percent to equal Wilt’s 50.4-point average. By comparison, to rise 36 percent above Ted Williams’s revered .406 batting average in 1941, a batter would need to hit .552 for an entire season.

On the macadam back alleys of Hershey, Kerry Ryman played for years with the basketball he stole at the game, a ball he took not for its memorabilia value (there was no sports memorabilia market in 1962) but to play with. Then he put it away, in his bedroom closet, and went on with his life. Soon after the Dipper died, though, Ryman, a crane operator still living near Hershey, put the ball up for auction in New York. It sold for over $550,000, the third-largest sale in sports memorabilia history; some in Hershey cynically said the sale of Ryman’s basketball proved that crime paid.

But almost at once, a controversy broke out. Two former Warriors officials insisted that when the Dipper scored the 100-point basket, referee Willie Smith took the ball out of play, to save for posterity; they insisted Ryman must’ve taken a replacement ball. Ryman was aghast as the auction sale was suspended. The auction house researched the matter over the next six months and then put the ball on the block again, saying in its catalogue that it still believed Ryman’s ball was the true 100-point ball. This time, the ball sold for considerably less, $67,791. Ryman’s dad told him he should’ve just burned that ball, anyway.

The players from that famous night went their different ways: Philly’s Paul Arizin went to work at IBM; Willie Naulls became a businessman, and is now a minister; Attles and Guerin became NBA coaches, Meschery a high school teacher and poet, Ruklick a writer who, for a time, served as the only white reporter on the staff of the historic black newspaper, The Chicago Defender. With great humor, Darrall Imhoff says that each year on March 1, thinking of Hershey, he breaks out in a rash.

Not until near the end of his life did the Dipper embrace his 100-point game. For decades, he had insisted that he was more proud of his record 55 rebounds in a 1960 game against Bill Russell. But in 1993, Chamberlain admitted, “People who know nothing about basketball or nothing about sports will see me and they will point to their little kid and say, ‘See that guy right there? He scored one hundred in a game.’ I know that it has been my tag. I am definitely proud of it.”

His words had the feeling of a father professing devotion to his long-lost son.

But he was still the Dipper, after all, and so he also said that if the Knicks hadn’t concentrated entirely on stopping him, he might’ve scored 150.

—

Gary M. Pomerantz is the author of WILT, 1962: The Night of 100 Points & the Dawn of a New Era, out in paperback on Three Rivers Press.