It was the summer of 2018 and Chris Paul was preparing for his second year with the Houston Rockets. That preparation included a very important meeting with his longtime stylist Courtney Mays.

The main focus of their discussion: How could they take advantage of the growing spotlight placed on Paul’s fashion and sneakers to send a message? And what would that message be?

They eventually settled on a plan to support Black designers and historically Black colleges and universities via school apparel. Though Paul went to Wake Forest, practically everyone else in his family attended an HBCU.

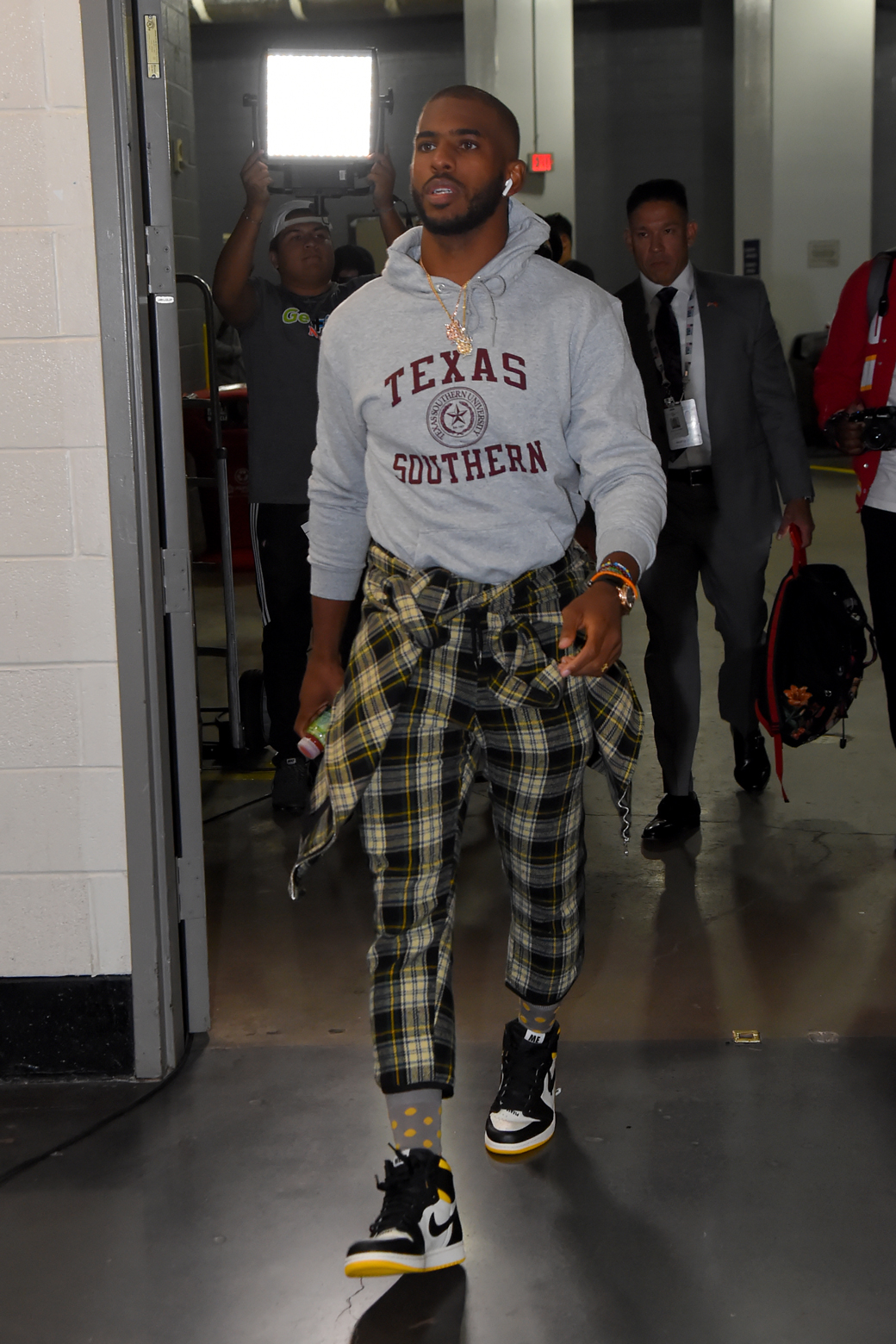

Shortly after, Mays made a visit to Texas Southern, her father’s alma mater. She went to the campus bookstore to purchase a souvenir and noticed a sweatshirt that looked perfect for Paul.

Fast forward to opening night at the Toyota Center. CP3 walked through the tunnel to the locker room wearing that hoodie. Cameras captured the moment; social media accounts shared it; reporters asked about it; blogs wrote about it.

Awareness started spreading. The plan started working.

“I remember wearing the Texas Southern hoodie and all the responses I got from people, like, I went there, I went there,” recalls Paul. “I think a lot of people need to know that some of their favorite people, whoever it may be, they are products of historically Black colleges and universities.”

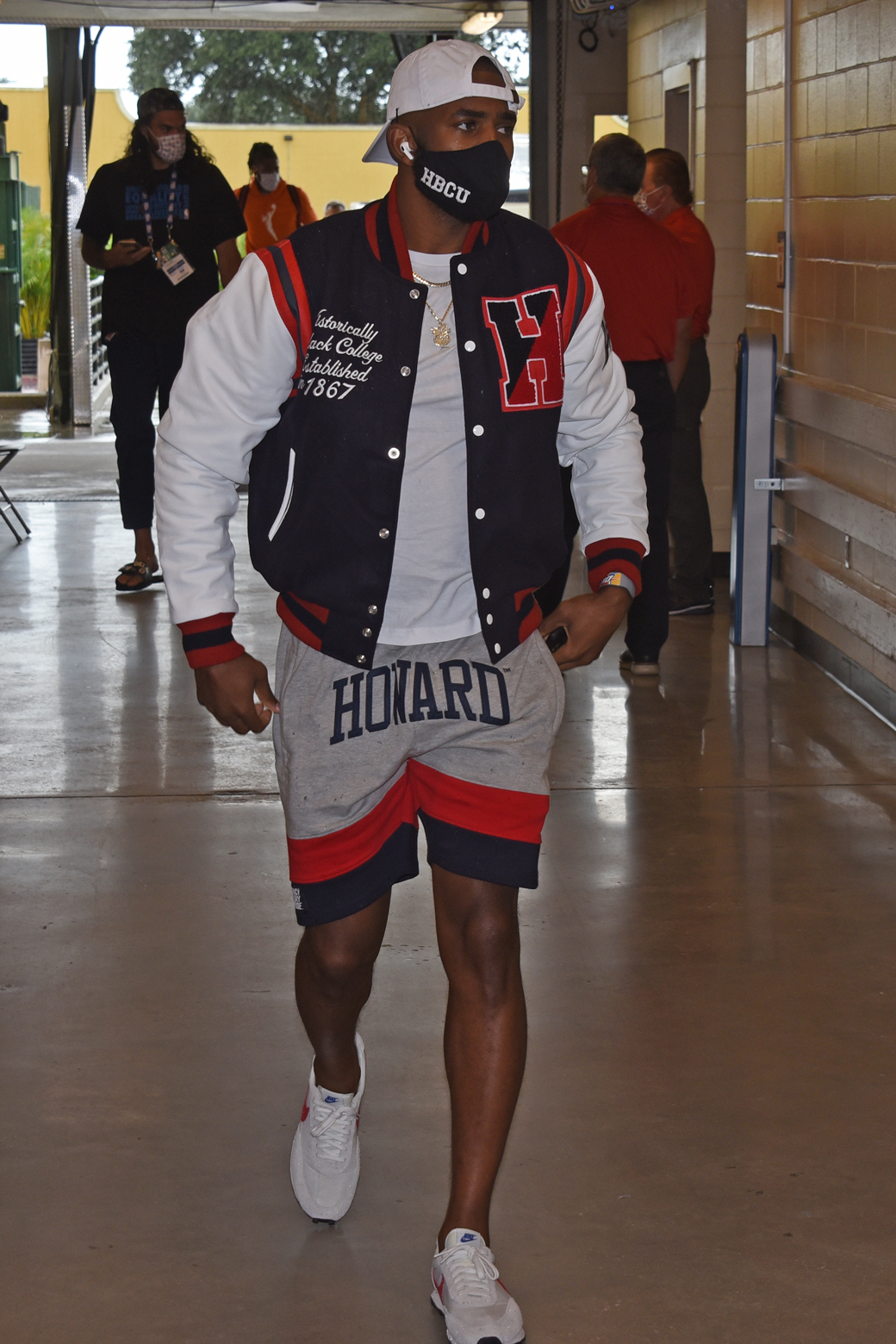

Two years later, with Paul preparing for the NBA’s 2019-20 restart in Orlando, the approach remained the same. He came up with an idea to use his Jordan sneakers as a canvas to celebrate different HBCUs in the Thunder’s eight remaining regular season games. (So far, he’s represented North Carolina A&T, Alabama A&M, Howard, Livingstone and Albany State. More to come.) Each pair has the respective institution’s name, logo and color scheme; and Paul has also written words on the midsoles related to the nationwide fight against racism and police brutality.

Mays worked to put together outfits that either matched the kicks directly or highlighted other notable causes. According to her, 99 percent of what Paul brought to the bubble is either made by a Black designer, promotes an HBCU or contains a social justice message.

With the HBCUs, the objective is to tell a complete story and really try to educate fans. Paul also partnered with Support Black Colleges, a clothing line founded by two Howard students, to assist at that goal. The company creates graphics for Paul’s Instagram to be posted after the games, providing additional information about the HBCU featured that day (location, motto, fun facts and more).

“Seeing how the tunnel walks have become this monumental moment—guys are watching the game but they’re also watching to see on social what the guys are wearing—we thought, Wow, we can use this moment as a storytelling opportunity,” Mays tells SLAM. “I feel like now more than ever I’ve found my voice and my purpose as a stylist with Chris, because we’re able to use fashion and sport to really champion things that are important to us.”

We caught up with Paul to break down that impactful mission.

—

SLAM: When did you realize the power of fashion and sneakers to convey certain messages?

Chris Paul: First, I want to say thank you to Courtney. I think a lot of times obviously people see me, as I’m the one out there playing and performing, but Courtney—she’s everything. We’ve talked about this and [saw] it all come together some years ago. We just talked about our platform. It started out with the opportunity to champion African American designers. It’s been so cool in the process not only to shed light on some of these designers who maybe at times wouldn’t be seen or get that platform, but I think it’s been cool for me to learn and get more educated.

SLAM: How has sneaker culture grown since the beginning of your career, giving players a bigger platform for expression?

CP: I’ve been in the League for a while now so I’ve had an opportunity to see a League when it was all about Nike iD. I’ll never forget how excited I was when the Brand finally put my shoe on Nike iD, because you felt like that was an opportunity and a way that you could tell stories. I designed a couple of shoes with my kids and that was storytelling. I think highlighting Black creatives and celebrating historically Black colleges and universities has been another opportunity to tell stories.

SLAM: Can you walk me through the decision to pay homage to a different HBCU in each game? Why was that important to you?

CP: Yeah, we got a crazy team. Obviously, that’s Courtney; it’s my little cousin AJ Richardson who went to North Carolina A&T; my brother who played his freshman year at Hampton University. We’re from the South. We’re from North Carolina. I grew up down the street from Winston Salem State University. We’ve known about the North Carolina Centrals, the Livingstones, the A&Ts, the Hamptons, the Howards—I could go on and on. So that’s naturally part of my culture. I’m one of the only people in my family that didn’t attend an HBCU. But deep down inside, I feel like I did or I wish I would have.

I think it’s really important to me because I’m one of those people who got a lot more interested in history as I got older. When I was a kid and going through it, I wasn’t really paying attention. It was just like, That’s that and that’s that. Now that I’ve gotten older, I’ve done a lot of research into HBCUs and see that they don’t get the same funding that a lot of these other schools get—different PWIs [predominately white institutions] and different colleges. What I’ve understood in doing the research is that a lot of these HBCUs are the schools that are educating our culture, our people. So why not try to make sure they can get the same recognition? Why can’t we try to make sure that they’re funded properly? I think that’s the thing when you look at the athletic departments. That’s the one thing that a lot of these big schools have on the HBCUs—the facilities. LeVelle Moton, who’s the head coach at North Carolina Central, which is a top tier program year in and year out—we’re trying to figure out how we can get them the same facilities that you see at Kentucky. Or Mo Williams, who is now at Alabama State. I think it comes back to the education of it. I think with everything going on now, it’s awareness. A lot of awareness. You got Kyle O’Quinn in the NBA who went to Norfolk State. I was walking this morning to the bus and talking to Darrell Armstrong, who went to Fayetteville State.

SLAM: What advice would you give to a high school player who’s considering going to an HBCU?

CP: I’m fortunate enough to have an AAU program. Year in and year out we have some of the top kids, so I’ve gotten an opportunity to know not only kids in our program but kids in other programs. I think for me, I don’t ever tell any kid what school to go to. But especially now, just tell them to understand their power and their leverage. It’s a different day in that if you can play and you’re talented, they’re going to come to you. So it doesn’t matter what school you’re at. If you’re at Winston Salem State, if you’re at Coppin State, if you’re at Norfolk State, if you’re at North Carolina Central, if you’re at any of these schools or wherever it may be—they are going to find you.

SLAM: You helped lead a master class at North Carolina A&T last year about sports, media and entertainment. What was the inspiration to do that?

CP: I was fortunate enough some years ago to go to a class at Harvard business school with this amazing professor named Anita Elberse. The class is amazing—you get a chance to do these case studies—and I’ll never forget it. And as I looked into things, I was like, Man, we’re doing these unbelievable case studies on all of these different people—there’s a Dwyane Wade case study, there’s a Jay-Z case study, there’s a LeBron case study, there’s one on Beyonce and many other people—this is a dope class. Why aren’t classes like this at HBCUs? So I reached out to [Elberse] and she didn’t hesitate. She was like, “Chris, just let me know what I need to do.” And so we partnered and we said we wanted to introduce it at North Carolina A&T. I’m telling you, this past summer when we had the introductory class, it was one of the best feelings I think I’ve ever had in life. To see an idea like that come together and to see students just engage in something and to see where it came from.

SLAM: You’ve also been inscribing messages on the midsoles of your sneakers, such as “Can’t Give Up Now” and “Breonna Taylor.” What’s the process of deciding what to write there?

CP: I do it in the locker room before the game. It’s funny, because people see “Can’t Give Up Now” and it’s got so many different meanings. Right now, it means we can’t give up as far as our struggle and fight for equality and social justice. Where it came from is—I listen to gospel music before the games. Most people would be like, What? You listen to gospel music to get you going before a game? One of my favorite songs since I was younger is a song by Mary Mary called “Can’t Give Up Now.” That’s why I write it on my shoes because I always listen to that song. If you listen to the song and it doesn’t touch you, something might be wrong with you. [laughs]

I also write Breonna Taylor’s name on my shoes every game because the cops still haven’t been arrested and we want to keep that pressure on [Kentucky Attorney General] Daniel Cameron and everybody behind him.

SLAM: As head of the NBPA, you were instrumental in getting the League to put social justice messages on the backs of jerseys. Can you talk more broadly about how the entire NBA is using the platform of the season to push for change?

CP: It’s been powerful and I think the coolest part is just to see how guys have come together. Guys have really connected. For some of these guys that you’ve been unbelievable competitors against, you never knew that you had so many things in common with them. Tobias Harris—I played against him, sort of knew him and whatnot. But here [in Orlando], I’ve gotten a chance to know him, Kyle O’Quinn and a few of those guys just from conversations about social injustice. I think it’s dope because at the end of the day, this is about unity and using this platform to amplify often-muted voices to effect change.

SLAM: You said previously that the new jerseys give a voice to the voiceless. Do you view messaging on sneakers the same way?

CP: No question. I say that because after every game, not every player goes up and gets the microphone. After a given game, a guy can score 15, but the guy who scores 32 is usually going to be doing the postgame interview. It’s a way to express yourself. It’s a way for you to say something that’s on your mind. And you may not want to say it physically, but you may want to show support to somebody or something like that. It gives you that opportunity.

SLAM: You recently helped launch the Social Change Fund, which will support pressing issues impacting the Black community. How did you, Carmelo Anthony and Dwyane Wade work together to start it?

CP: We’ve all had an opportunity to do so many different things on our own over the years. This was an opportunity for us to come together. And that rarely happens, especially in sports because everything is always verses, you against them, I can do this better than you. But it was all about igniting conversations around issues like police brutality, educational reform, systemic racism—all these different things. And what we want is other guys who are passionate about those same subjects to join. It’s not something that we put together to be divisive. The Social Change Fund is inclusive. Anybody that wants to be a part of it, they’re welcome.

SLAM: Lastly, just want to give you an opportunity to pass on a message to the next generation or spread any message that you’d like regarding social justice and the fight for equality.

CP: I think the biggest thing is—a lot of times guys wonder, Is it OK to say this? Can I do this? Is it the right time? I think you just have to be comfortable with yourself and know who you are, especially as athletes. And don’t ever look at yourself as being just an athlete. Because at the end of the day, I’m a husband, I’m a brother, I’m a child, I’m a father. All of those things come before being an athlete. So historically, athletes as advocates have been so important in raising awareness to create change. You look at people like Muhammad Ali, Tommie Smith, John Carlos and Colin Kaepernick. We can make a difference.

—

Alex Squadron is an Associate Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @asquad510.

Photos via Getty.