In a culture of cool, the “It” factor is something that is difficult to explain but intrinsically recognized. “It” cannot be heard, seen, bought or sold, yet it still exists. “It” is the difference between why we love Derek Jeter and never liked A-Rod. “It,” among other variables, has to do with relatability—a factor that is intangible though deeply felt.

Other sneaker brands may have the look, utility, engineering and even a hip caché. But they are missing “It.” This is what PONY has always had, and perhaps nobody has more “It” than them. While “It” is not unique to the brand per se, an almost universal response to the presence of PONY is a knowing tilt of the head and a nod of approval to the one sporting them.

The execs at PONY know well enough the reaction their brand gets and are, as a corporation, focused on their standings rather than their stats. PONY has never been and will never be the No. 1 selling athletic shoe. This is a fact that the makers, marketers and fiscal advisory team proudly do not plan to change. Why? Because not being the best—and far from the biggest—is precisely PONY’s recipe for success. To still be in the game after 44 years is a testament to PONY’s fascinating legacy and uncommon narrative of survival. While the life expectancy of a pony is 40 in the equine world, very few companies are still breathing after nearly five decades in the footwear business.

Back in 1972, Roberto Mueller had an epiphany while working for Levi’s. He wanted to take the personalized connection one has with jeans and apply it to a sneaker. Using the city’s 8 million people and more than 800 languages crammed into 305 square miles as inspiration, PONY (Product of New York) utilized the city zeitgeist by applying it toward the shoes’ innovative engineering, reasonable price points and daring colors. Placing a Chevron on its side and deploying the acronym of its city on the tongue, Mueller’s 1972 sneaker, “The Starter” painted a vulcanized leathery picture of a time and town that was then and is still like no other.

Formed in Mueller’s Madison Ave and 59th Street offices, PONY was and still is the only authentic sports brand ever to come directly out of NYC. Their 1975 Top Stars were made to be consumer friendly and designed with performance athletes in mind. The sneaker achieved its aim and something more: the unintended consequence of being coopted by urban counterculture. Fusing sports and fashion, PONY spoke to kids in a dynamic and forever sort of way. In the early ’70s, adidas and PUMA had a similar urban swagger, and PONY swiftly infused itself in the pavement credibility conversation. As Mueller and his team were soon to find out, the currency of “It” is worth millions.

So enthralling was the PONY brand that it attracted world-class athletes from diverse disciplines such as Muhammad Ali, Reggie Jackson, Franco Harris and Pelé. They even made a sizable presence on the hardwood. From 1977-79, PONYs were seen on the feet of over 50 NBA players: Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, David Thompson, Bob McAdoo, John Havlicek, Paul Silas and Darryl Dawkins were just some of the brand ambassadors infiltrating basketball arenas all over the country. PONY still remained, at its core, a product of New York. The city’s youth leagues in the Lower East Side, Bronx and the Holcombe Rucker Tournament in Harlem gladly received the company’s sponsorship and proudly sported PONY t-shirts.

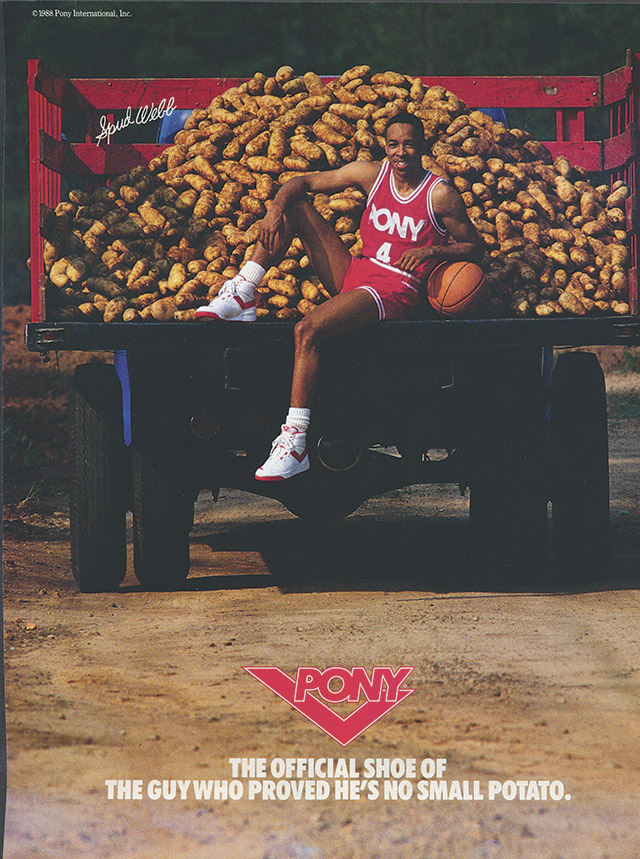

In equine terms, ponies are distinguished mainly by being smaller than horses. Apropos, the height of PONY’s impact came on February 8, 1986 during All-Star Weekend in Dallas. The smallest horse in the pack—Spud Webb, at 5-7—laced up his red and white (with black pinning) low-top PONY City Wings and literally flew past Michael Jordan, Patrick Ewing and Dominique Wilkins to win the Dunk Contest. PONY cashed in on Mr. Webb’s feat while simultaneously putting Nike on blast with their slogan: “Why get air when you can fly?”

Soon after, and after years of an accruing personal debt, company founder Mueller sold his majority share and PONY was essentially put out to pasture. Kids on the corners lost their enthusiasm for the brand and aside from Louis Orr in ’88 and Wilson Chandler in ’09, no one in the NBA—or other pro sports— really wore PONY sneakers. PONY’s revolving and unstable rotation of ownership, questionable designs (at one point losing the chevron), continual headquarter upheaval (from Manhattan to San Diego, L.A. and overseas) created a fissure with its fan base and led to a decade-long deflation.

Despite the dysfunctional corollary of ill-advised changes with chronic production ruptures, the PONY flag was somehow never completely taken down. Though in severe need of mending, PONY has been reclaimed in 2015 and has the correct leadership in place to patch up its frayed relationship with brand loyalists. The first move in PONY’s redemption was bringing the corporation back home. “PONY can only live in New York,” says Alexander Cole, whose company, Iconix, is now the majority owner. As he recently accomplished with his other old-school sportswear acquisition of Starter, Cole insists on honoring PONY’s iconic marketing and licensing legacy with a banner of modernity.

Partner and product development maestro Santino LoConte adds, “We want to revisit what worked and bring it to today’s standards.” LoConte and Cole’s reinterpretation of PONY is based in the lifestyle market. These modern translations of archival shoes use original designs, toolings and silhouettes with an updated contemporary lens. This means fresh leathers, ergonomic insoles, rubber outsoles and new embellishments. The fall monochromatic color palette of the 2015 Product of New York Collection features black, white, grey, crew and oxblood.

Even Spud Webb loves seeing them back at it. “It’s great to see PONY relaunching the brand,” he says. “The brand was with me during the Dunk Contest and throughout my career.”

Team PONY has also taken complete advantage of its local real estate by collaborating with Ronnie Fieg, Reed Space, Mark McNairy and DKNY, all deeply rooted in NYC style and culture. PONY Chevron Classic is Cole and LoConte’s notion of a throwback collection. Understanding trends but mindful of Mueller’s ’70s Madison Avenue blue-collar raison d’être, the PONY Chevron Classic line pulls proportionally from the past. This widely distributed 20-style offering revisits PONY’s readily accessible price points in a renewed package, using high quality materials and components that maintain its handmade craftsmanship. Urban Outfitters and Madewell have been happily shelving these fresh grail finds.

PONY’s New York brass has also been in conversation with athletes to be their next ambassadors. They maintain they want someone from the area. Though, when asked if they reached out to a current Knick, both Cole and LoConte gave a look as if to say, “We are in the business of selling shoes—why would we do that?”

The sneaker industry is no longer the outsider looking up to the runway elite. Sports fashion lifestyle brands are now tastemakers. Yet PONY’s message is essentially the same as when it began 44 years ago. True to its demeanor, heritage and even species, it is delusional to think that PONY 2015 will make a major dent. Fittingly, Cole and LoConte now aspire to ride this PONY toward a slightly alternative horizon. The adage “strength in numbers” has been knocked off the high horse of the sneaker world from the 16th floor showroom in midtown Manhattan, where PONY executives dare to suggest that their strengths lie in their limitations. And what they have going for them in abundance is the city they call home and a history that is cool.

The PONY story is a narrative of a product with little more than “It,” but continues to be so much more to so many.