When Michael Jordan was drafted into the NBA in 1984, he joined a rapidly changing league in a rapidly changing world. Five years earlier, Magic Johnson and Larry Bird had carried their collegiate rivalry over into an NBA that had recently merged with the ABA. Along with star Julius “Dr. J” Erving, the NBA had gotten a big dose of high-flying athleticism as well as the ABA’s three-point shot. The 1981 NBA Finals would be the last shown on late-night tape delay. The ever-expanding fan base was ready for new stars, new champions—and a new shoe.

Nike too was at an interesting crossroads in 1984. They’d recently been passed by Reebok for the No. 1 spot in America, thanks to the Boston-based company’s garment leather aerobic shoes that Nike didn’t have an immediate answer for. Basketball, meanwhile, was something of an untapped market. Nike had made a splash with 1982’s Air Force 1, but the majority of superstars—including Dr. J, Magic and Bird—wore Converse. This was just the way it had been, ever since a salesman named Chuck Taylor got his name on the canvas All-Star back in the ’20s. There were notable exceptions—Puma’s Clyde, adidas’ Jabbars—but signature shoes were just that: exceptions.

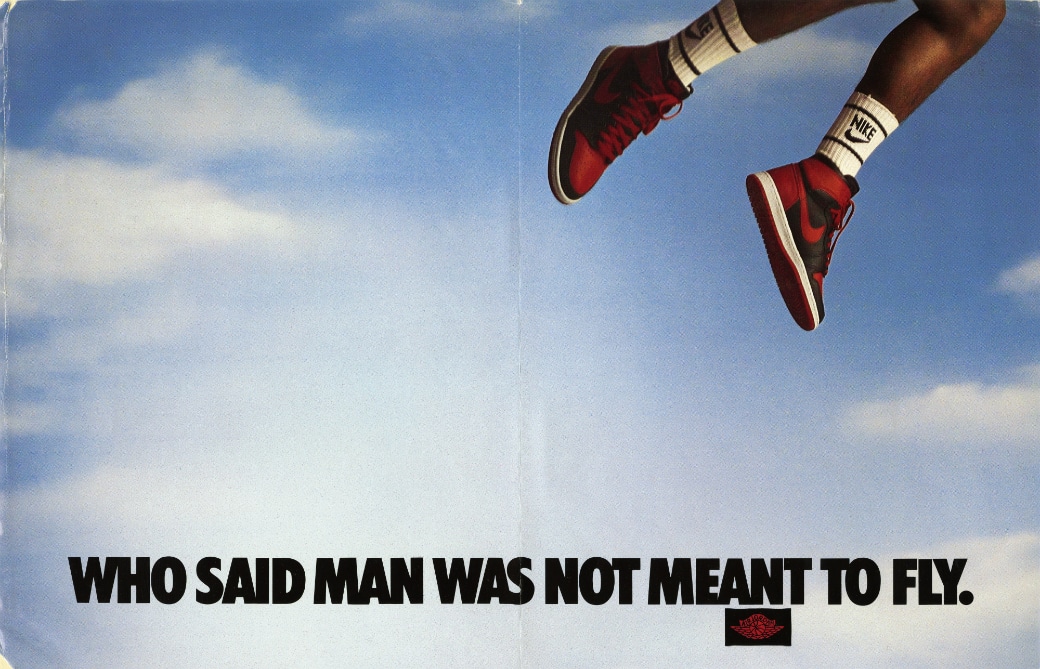

For Nike, Jordan represented a huge opportunity if they could sign him. Jordan himself wanted to wear adidas, the brand he wore in high school. But Nike had a plan where other brands didn’t, to not only give Jordan a (for the time) big contract, but to also take his input and create a shoe just for him. And then, beyond that, to give the new shoe a marketing push unlike any that had ever come before. Jordan himself would debut the shoe early in the NBA season, and it wouldn’t go on sale until April of the following year.

If it’s hard to separate the Air Jordan I from sneaker culture, it’s because most of what we know as “sneaker culture” sprung up around the Air Jordan I itself. Much of what we take for granted today simply didn’t exist until the Air Jordan was created. The TV commercials, the limited production numbers, the cult of personality itself—Jordan spawned all of this.

First of all, think of the world as it was in 1984. So much was new, from personal computers to cable TV to hip-hop. For a kid in 1984, there was so much to discover: Atari 2600s and Commodore 64s, ESPN and MTV, Run-DMC and LL Cool J. All of it sudden, it seemed there was so much MORE of everything. As for the NBA, there was the ongoing rivalry of Magic and Bird, Dr. J was flying high for the Sixers, and the year prior the league had introduced yet another ABA innovation—the Slam Dunk Contest.

For Nike, the time couldn’t have been better to introduce something new. And, given their timeframe, what happened next was perfect—the NBA banned their new shoe. Well, not exactly. What they banned was a custom version of the Air Ship, an inline shoe and Air Force 1 successor that had been made up in the Air Jordan’s black-and-red color scheme. It didn’t fit the uniform code, the NBA said, and it was out. Nike responded by doing two things: They created a version of the shoe that added white panels to the black and red upper, meeting uniform regulations. And they turned the ban into that famous TV commercial.

When the ban came down, the NBA season hadn’t started yet, and the shoe wasn’t set to go on sale for another six months. It was the kind of publicity that you literally can’t buy. Jordan talked up the shoe on TV with David Letterman, then wore the “banned” black-and-red model in the 1985 Slam Dunk Contest, along with a matching nylon tracksuit. He stripped off the tracksuit after the first round, and lost the competition to Dominique Wilkins, yet still caught the ire of other All-Stars. “Michael is a rookie and he still has a lot to learn,” said the Spurs George Gervin, “just like we all did.” Well, not so much.

When the Air Jordan finally released in April of 1985, the hype had built to a fever pitch. Jordan, voted in as an All-Star starter, was well on his way to Rookie of the Year honors. And with jerseys still being something of a specialty-store item, his shoes were the best way for fans to show allegiance. According to the language of Jordan’s initial five-year, $500,000 per year deal with Nike, the last two years would become guaranteed if he sold $4 million worth of shoes in the deal’s third year. Instead, Air Jordan did $100 million worth of business in the first 10 months. Air Jordans were everywhere.

The outrageous success of Air Jordan would change everything when it came to basketball shoes. The year before Jordan was drafted, the biggest sneaker deal was No. 1 pick Ralph Sampson’s deal with Puma. Jordan’s former college teammate James Worthy, the No. 1 pick in 1982, had signed with New Balance for $150,000 a year. Now, with Air Jordan under his belt, agent David Falk could get a huge deal—with adidas—for Knicks center Patrick Ewing, the first overall pick of 1985. They’d go on to sign Run-DMC too, after the group released a song called “My Adidas” in 1986.

But while other brands played catch-up, Nike was off and running. The original Air Jordan I stayed on shelves for over a year before being replaced by the Air Jordan II, a sleek, Italian-made shoe that did away with the Swoosh entirely and left Jordan’s ball-and-wings logo as the only overt branding outside of a block-letter NIKE on the heels. And the Jordan I’s DNA carried forward in the Dunk, a collegiate model done up in all sorts of team colors. The Georgetown Hoyas, Patrick Ewing’s alma mater, even got their own shoe—the Terminator, made up in navy and grey with HOYAS across the heels.

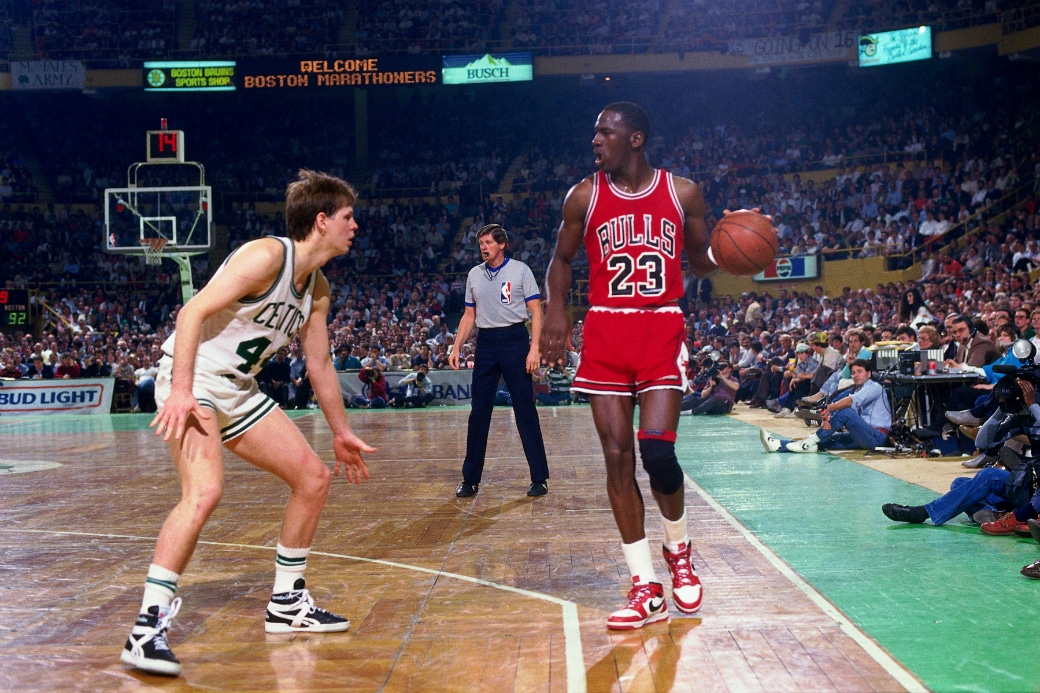

There were missteps of course, both figurative and literal. Following the immense initial success of Air Jordan, Nike produced millions more pairs, many of which wound up selling for far below the suggested $65 retail price. And Jordan himself would break his foot in just the third game of his second season, knocking him out for nearly five months, including the All-Star break. (He’d return in time to play 15 more regular-season games before turning in a legendary playoff performance—63 points at Boston Garden!—against Larry Bird and the Celtics. In Jordan Is, of course.)

Following that Celtics sweep, Jordan himself wouldn’t lace up a pair of Jordan Is for an NBA game for another 12 years. He never planned on wearing them again. But before what he expected to be his final regular-season game at Madison Square Garden in 1998, he’d found an original pair in the back of a closet and thought it would be cool to wear them one last time even though they were a size too small. He scored 42 points, putting one last mark on a world he—and his shoes—had made.

—

GRAB YOUR COPY OF SLAM PRESENTS JORDANS VOL. 4!

Russ Bengtson is a freelance writer. He tweets @RussBengtson.

Photos via Nike and Getty Images.