Billy Donovan remembers 20,000 people coming to the Superdome—to watch practice. And he can’t forget how long the jog was from the locker room to the court. It was a long trip, but it had nothing on the journey the Friars had taken from Big East obsolescence to the college mountaintop.

For the first seven years of the league’s existence, Providence finished either last or next to last, a slap to the face of former Friars coach Dave Gavitt, one of the Big East’s founding fathers who at the time served as league commissioner. If it hadn’t been for Seton Hall’s even greater futility at that time, Providence would have been the conference’s biggest charity case.

In 1985, a fast-talking New Yorker who had won 64 percent of his games over five years at Boston University and had spent the previous two as an assistant with the Knicks took over. At his introduction, Rick Pitino told everybody to forget investing in the stock market; Providence basketball tickets would provide a much better return. People laughed at that, and Providence Journal writer Bill Reynolds ripped him. “I told Bill in 1987 that if he bought eight season tickets, he would have gotten rich selling them,” Pitino says, laughing.

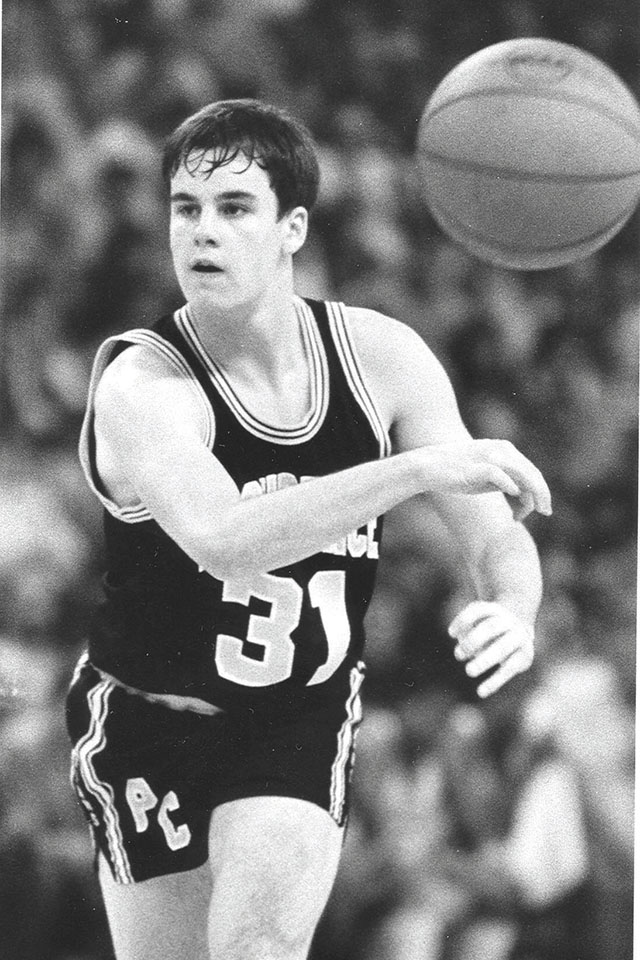

At his first team meeting, two players showed up 30 minutes late, according to Donovan, and Pitino made them run five miles six days in a row at 5 a.m. (30 minutes = 30 miles). He was hardly impressed with his roster, which included 10 guys “who were not any good,” Pitino once said. The 5-11 Donovan, at a robust 191 pounds, was one of them. Donovan wanted out, and Pitino was happy to accommodate him. One problem: Northeastern and Fairfield, Donovan’s two preferred destinations, didn’t want him. So, Pitino told the guard to lose 30 pounds and come back ready to run and press for 40 minutes.

“He told me, ‘If you do everything I ask, you will have the greatest year of your life,’” Donovan says.

The first year was great. Providence finished fifth in the Big East, won 17 games and made it to the NIT quarterfinals. The next season was even better. The Friars reached the Final Four, and their jaws were agape at 20,000 people watching layup lines. “It was a crazy setting,” Donovan says.

Nobody worked harder than the Friars, who practiced three times a day before the NCAA instituted its 20-hour rule limiting activity. Nobody ran like them: playing 94 feet every second of the game. And nobody shot like them: After experimenting with the three-point shot for a few seasons, the NCAA made it universal in ’86, and thanks to Pitino’s experience with the Knicks, he understood its importance and how to exploit it. In a conference known more for bloody noses than rainbow jumpers, Providence’s long-range assault was unheard of.

“We used the three-pointer to our advantage,” says Carlton Screen, a freshman guard on the team. “Our goal was to take more threes than the other team. We also wanted to defend the three-point shot better than anybody. We did both very well.”

* * *

Pitino wanted the Friars to jack up three-pointers in ’86-87, but it wasn’t until Providence took on the Soviet Union in an exhibition before the season that the coach realized even he had underestimated how often the team should launch threes. The Soviets had finished second to the US at the ’86 World Championships and were aficionados of the trey ball.

“We felt like if we took 12-15 threes a game and made five, we would lead the nation,” Pitino says. “That night, I think we took 18, and the Russians took 30. I realized my projections were too low. We changed our estimates to 23 to 25 a game.”

While the Friars were working to increase their output from beyond the arc, the rest of the Big East was approaching the area behind the line as if it were a moat filled with crocodiles. Coaches like Syracuse’s Jim Boeheim, Villanova’s Rollie Massimino and St. John’s Lou Carnesecca regarded the three-pointer as blasphemy. For the season, Providence averaged 19.5 3PA per game, which was more than the Orangemen, Wildcats and Red Storm combined (19.1). And since PC made 42.1 percent of its shots from deep, it was getting tremendous return on its long-distance service.

The approach was pretty basic. Donovan would either launch from beyond the top of the key off a screen when a defender was too lax, or he would penetrate and kick to either Delray Brooks or Ernie “Pop” Lewis on the wing. Donovan and Lewis took more than 220 threes apiece that season, and Brooks put up 157. Each shot above 40 percent behind the arc.

“We were a whole bunch of guys who hadn’t played much before Rick got there, and we were just thrown into the river,” says Jacek Duda, a center on the team. “Rick made everybody believe in themselves, and after that Soviet Union game, we just shot more from behind the arc. It was great.”

Donovan made the transformation from a chubby reserve into “Billy the Kid” and Pitino was quick to outfit him in a cowboy hat and boots for the ’86-87 media guide. Even more impressive was Brooks’ metamorphosis from a beaten-down former prep phenom into a key piece of a Final Four team.

Brooks was such a heralded prep player that Indiana’s Bob Knight invited him to the 1984 Olympic trials. But when the ’84 USA Today POY reached Bloomington, he struggled in Knight’s structured setting and didn’t respond well—as many did not—to Knight’s abuse and constant haranguing. He transferred from IU to Providence halfway through the ’85-86 season, and Pitino set about the business of building his confidence.

“When you play for Bob Knight, you can either be broken down or fall in line,” Pitino says. “He came to me a beaten guy, and I had to get his confidence going. It worked out great.”

When Pitino took over, the Friars were a casual bunch who enjoyed hanging out and weren’t pushed too hard in practice by kindly coach Joe Mullaney. But early on, the Friars learned that while they were good-time buddies, they weren’t all that close. Pitino challenged them to learn more about each other, the better to build a tight link on the court. He supplemented that bonding with a grueling practice schedule that included three workouts a day, along with late-night two-on-two games involving the coach. “During our first meeting, Coach Pitino told us we would be the hardest working team in America,” Screen says.

During Pitino’s two seasons at Providence, he stressed basketball and academics; that was it. Graduate assistant Jeff Van Gundy was in charge of making sure the players attended class. “If you were one minute late, you ran at 5 the next morning,” Screen says. There was individual instruction, walk-throughs, film study and three-hour afternoon workouts. At night, Pitino and Lewis would challenge Donovan and Brooks. “I was in pretty good shape then,” Pitino says. “The games were pretty even.”

Fueled by hours of prep and ready to shoot the three-pointer at all times, the Friars went at the Big East bullies and thrived. Providence finished 10-6 in league play, its best-ever conference mark. When Georgetown visited, the Friars earned a win with late triples by Brooks and Lewis, and Pitino almost got in a fight with Hoyas coach—and PC graduate—John Thompson. Thompson was shouting at Pitino, and Pitino wouldn’t back down. They had to be separated at midcourt.

“I was standing there, looking at his navel, ready to fight him,” Pitino says, laughing at the image. “After the game, he put his arm around me and said, ‘I’m proud of what you’re doing with my alma mater, but when you come to Georgetown, we’re going to kick your ass.’”

Georgetown did rough up the Friars in DC. And the Hoyas handed Providence an 84-66 defeat in the Big East semis. But the Friars were headed to the tourney for the first time in nine years, and that was big. Providence rolled past UAB in the first round, 90-68, behind 35 points and 12 dimes from Donovan. But things weren’t so easy in the second round against Austin Peay. In fact, it took some good fortune for the Friars to survive, but they did, barely, winning 90-87.

Next was a talented Alabama team, but Donovan’s 26 and Brooks’ 23 propelled a 103-82 rout and set up a regional final with…Georgetown. After the Big East tourney loss, Pitino assured the Friars they wouldn’t have to see the Hoyas again. Now, he was saying Thompson’s team was an easy mark.

“I told them they were the luckiest bunch of guys I had seen,” Pitino says. “I said, You don’t realize it, but there is only one team that isn’t afraid of you. They’re going to take you so lightly that it will be a cakewalk to the Final Four.”

And it was. Georgetown pushed its defense out to the three-point line, so the Friars went inside. Providence attempted only nine treys—12 fewer than the Hoyas—and Donovan and Brooks drove and fed the big guys. Donovan scored 20, but so did forward Darryl Wright. Big man Steve Wright had 12, and forward Dave Kipfer added 11 in a surprisingly easy 86-73 win.

“Before the game, [Pitino] told Delray and I that we couldn’t shoot the ball,” says Donovan, who attempted only five shots but was 16-18 from the line. Brooks took two shots. “He said he wanted us to pass the ball.”

If there was one team the Friars didn’t want to see in New Orleans, it was Syracuse. The Orange had three future pros: guard Sherman Douglas, forward Derrick Coleman and center Rony Seikaly. “They had our number,” Pitino says. Cuse gained a 36-26 halftime lead and held Providence to 36 percent shooting (26 percent behind the line) in a 77-63 win. The magic ended.

But the memories remain rich. “We defied a lot of logic,” Donovan says.

Duda still marvels at the turnaround keyed by a coach whom players thought was “completely crazy.” And Screen simply calls it “an unbelievable ride.” Pitino has won two national titles and countless games since, but considers that ’86-87 season perhaps the most important of his career.

“I’m in my 42nd year of coaching, and because of that Cinderella team, I believed for the rest of my coaching career that anything was possible,” he says. “Any comeback is possible, and any team can accomplish great things. Providence kept that alive for me.”

—

Photos courtesy of Providence College Media Relations