‘The Black Fives’ Tells the Monumental History of the Black Pioneers Who Revolutionized the Game

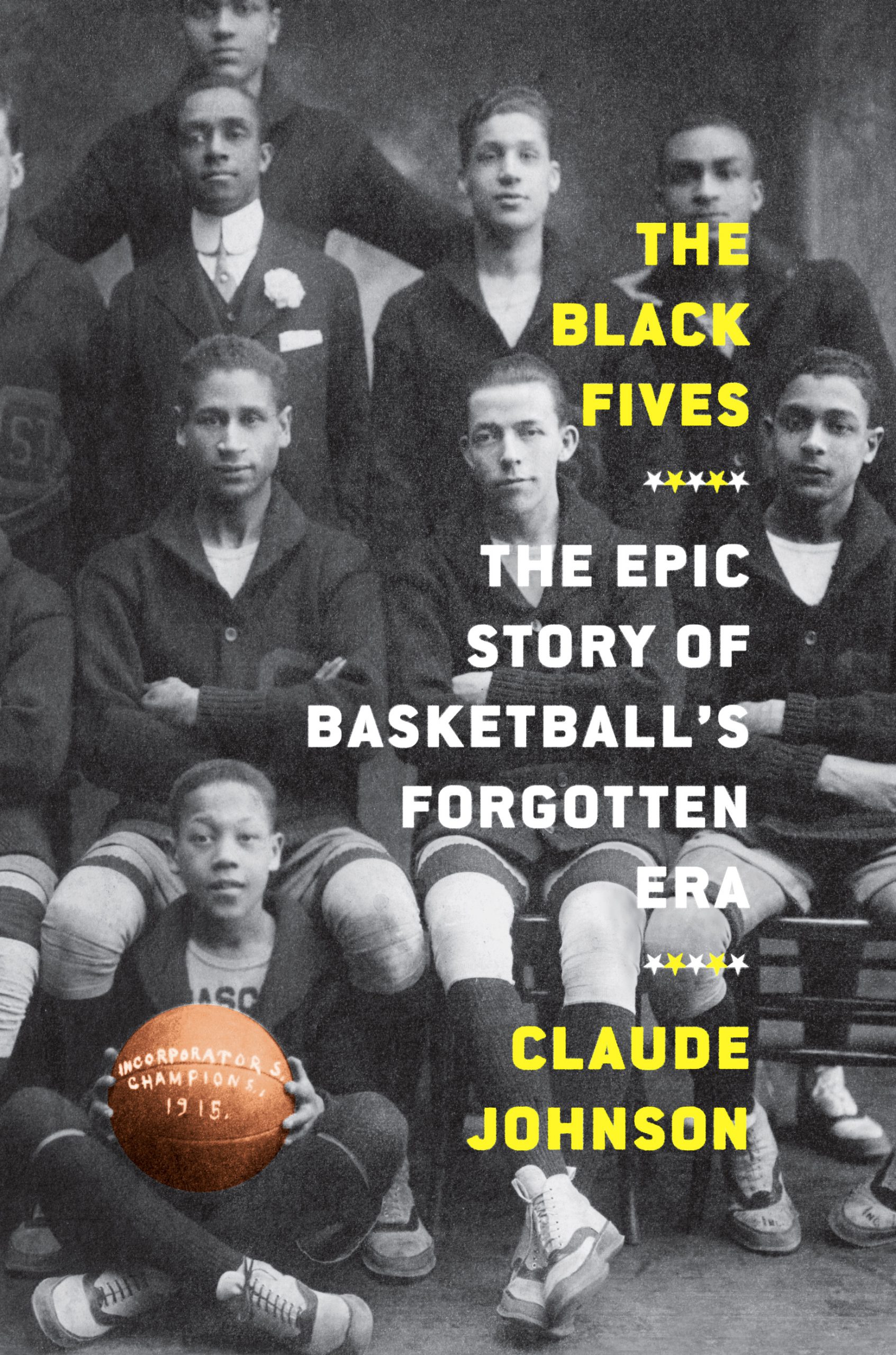

Historian Claude Johnson has spent more than two decades researching and honoring the history of some of the game’s more revolutionary pioneers. Following the racial integration of professional leagues in the 1950s, dozens of African American teams, which were often called “fives,” were founded. In his new book, THE BLACK FIVES: THE EPIC STORY OF BASKETBALL’S FORGOTTEN ERA, Johnson rewrites our own understanding about the true history of the game, while spotlighting those who helped revolutionize basketball as we know it today.

From the visionaries to the managers and all of those who helped blaze a trail while battling discrimination, the Black Fives helped strengthen and uplift their communities during Jim Crow.

Below is an excerpt from Johnson’s new book, which you can purchase here:

CHAPTER 26

“TRUE WORLD CHAMPIONS”

FEBRUARY 19, 1937, was a big night in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. That’s because the Oshkosh All-Stars, a local all-White basketball team, were on the eve of playing in a “World Series of Basketball” that would put the small city and the state of Wisconsin on the national professional hardwood stage.

Their opponents were the all-Black New York Renaissance Big Five. One would think that in the Midwest, during the Great Depression, and during Jim Crow, that the appearance of an African American team in an all-White town would be of concern. But actually, the Rens were universally considered the champions of basketball, and Wisconsin residents were some of the country’s most passionate basketball fans. So they eagerly welcomed the visitors.

Wisconsin was not new to interracial basketball. The Renaissance Five had begun visiting Wisconsin in 1934. That year the Milwaukee Raynors, an all-Black club, barnstormed the state from their home base of Milwaukee. The Milwaukee Colored Panthers were also popular, and the all-Black Chicago Crusaders toured through Wisconsin during the mid-1930s.

Formed in 1931, the Oshkosh All-Stars had played the Rens for the first time in February 1936 in a two-game series. The games drew so many specta tors that local promoter and Oshkosh team manager Lon Darling decided to do it again in 1937. This time the two squads staged a five-game series to be played in Oshkosh, Racine, Green Bay, Ripon, and Madison. Darling declared that the winner of the series, which the papers dubbed the “World Series Of Basketball,” would be considered the world’s champions of basketball.

“It was a money-maker,” recalled former Renaissance Five star and future Basketball Hall of Fame member John Isaacs. Each venue saw huge attendance, and in local newspapers, race as a point of difference was rarely mentioned. It seemed to matter only as a descriptive term. Prejudice was, if not trumped, at least mitigated by love of the game. According to Isaacs, on this trip the Rens were able to stay in hotels and eat at restaurants like everyone else. “We had trouble when we first started with all these white All-Americans, and when we first started playing them, damn near every night we had to knock one or two of them out,” said the Rens travel secretary and road manager, Eric Illidge, many years later. “For two or three years straight, two or three jaws were broken,” he continued. “Every night, every GAME we played, we had a fight, not with the customers but with the players themselves—they couldn’t stand us beating them,” said Illidge, whose only concern was keeping the score down so they would get invited back. “I had two fighters on the team, they broke about four or five different jaws, Pop Gates and Wee Willie Smith” he explained. “And we kept doing it until everybody respected us.” Illidge had no regrets. “My job with the Renaissance was easy and I’ll tell you why, we had the best team at that time in basketball,” he said. “We was the biggest drawing card in basketball.” His duties included making sure players would “leave on time, be at the game on time, check the gate receipts, collect the money, give them their lunch money, in fact, I took care of all the business.” Yet, Illidge was always prepared for inevitable trouble. Often, the cash accumulated so fast that he had to wire it back to Harlem using Western Union, unless it was close to payday. “All this goddamn money in my pocket,” Illidge said. “One time in Louisville some guy came and grabbed me and tried to take my money off of me, but, he was so scared,” Illidge laughed. “I had my pistol in my pocket, and I stuck it in his jaw, and he flew!”

While the Rens faced all kinds of challenges on the road, none were as bad as what happened to the New York Harlemites, an African American barnstorming squad based in St. Louis. While driving toward Chester, Mon tana, on February 6, 1936, for a scheduled game, they encountered a blizzard. Their car broke down and “the entire party was forced to get out and walk to a farm house three miles away,” according to the Fort Benton River Press. “The lowest reading of the thermometer was approximately 42 degrees below zero” that week, the paper reported. They were rushed to nearby Shelby for medical attention treatment of “frozen faces, feet and hands.” They continued playing on schedule into March, when it was reported that the players, whose frostbite injuries had “necessitated their playing with their hands taped, are again able to play without bandages.” About 260 people showed for the game, which the Harlemites won, 44-43, and “the colored artists performed perfectly despite the loss of their classy forward who died at Shelby when gangrene set into his hands after they were frozen near there during the recent blizzards.”1 The twenty-six-year-old professional basketball player, Benson Hall, had lost his life after being sent home “because his mother back in St. Louis refused to let them amputate parts of his body,” according to the daughter of Donnie Goins, one of his teammates.

Getting back to the Rens, just in case, their team bus, a custom-made REO Speed Wagon, had two potbelly stoves on board for heat. These also served to dry their sweat-soaked woolen uniforms when it was too cold to let them air-dry with the windows open. “The bus was your home, when you come to think of it,” said Isaacs in 1986. “The hard part wasn’t the playing, it was the traveling.”3 Still, according to Isaacs, the Rens’ game strategy was always the same. “Get ten points as quickly as you could, because those were the ten points the refs were gonna take away.”

Meanwhile, the Oshkosh All-Stars were trying to build a case to join the National Basketball League, a proposed new circuit of teams from the Midwest representing both large and small companies, from the Akron Firestones and Akron Goodyears to the Indianapolis Kautskys and Richmond King Clothiers. This league was still only just an idea at the time. The All-Stars lost that 1937 series with the Rens, three games to two, but Bob Douglas agreed to a return engagement, a two-game series in March 1937.

Ever the shrewd promoter, Darling declared that those two extra games would extend their previous “World Series” to seven games. In other words, if the All-Stars won both, they would be the new world champions, instead of the Rens. The All-Stars managed to pull it off, and the following season the NBL added Oshkosh as a founding member.

Beyond delighting Wisconsinites, the series between the All-Stars and the Rens served a purpose for basketball fans around the country: It helped to determine which top-notch team was truly the best. For a long time, any team (like Will Madden’s Incorporators) could claim they were “world champions,” and often the public was understandably confused. Behind the scenes, promot

ers took notice. A team’s won-loss record might speak for itself. But no hard stats could prove the greatness of a barnstorming team without a doubt. Which was why Edward W. Cochrane, a Chicago Herald-American sports editor, came up with the idea for a World Championship of Professional Basketball. “At the time there were no less than a score of professional basketball teams, all advertising themselves as world’s champions,” Cochrane remembered in 1941. The annual tournament was born “out of the chaos of these conflict ing claims,” he said. So, they decided to settle the chaos once and for all. The clear-sighted inclusion by the Herald-American of all-Black teams from the outset gave legitimacy to the tournament as well as to pro basketball itself. Twelve teams were invited to the inaugural tournament in 1939, the best pro teams in the country, including the New York Rens, Oshkosh All-Stars, Harlem Globe Trotters, and New York Celtics. It tipped off on March 26, at the 132nd Regiment Armory in Chicago, a cavernous drill hall, where eight thousand fans saw the Rens defeat the New York Yankees 30–21. The follow ing day, the Rens took down the Globe Trotters, 27–23 at Chicago Coliseum, a historic structure that had been the site of six Republican National Conven tions and the home of the Chicago Blackhawks early in their existence. Bob Douglas and his Renaissance Five had made it to the final, which was played on March 29 against their familiar rivals, the Oshkosh All Stars. New York triumphed, 34–25, making headlines across the country. But when champi onship jackets were awarded to the players, star guard John Isaacs famously borrowed a razor blade from a teammate and carefully removed the stitches that attached the word colored off of the back of his, so that it read, simply, world champions.

John William Isaacs, aka “Boy Wonder,” a bruising, powerfully built six-foot, three-inch, 190-pound guard, was a star player from East Harlem. He led his Textile High School squad to the 1934–5 Public School Athletic League championship, with a defeat of New York City powerhouse and defending PSAL champion DeWitt Clinton High School. Following a successful 1935–6 season, Textile lost in the city PSAL playoffs when Isaacs, being twenty years old, was ruled ineligible to play in high school.”4

Being ineligible had its perks. Isaacs played games with the St. Peter Claver Penguins, a Brooklyn-based “colored” team that featured Puggy Bell, a future pro teammate, and in the fall of 1936, he appeared with the New York Collegians, another all-Black squad.5 These brief stints not only proved that Isaacs could play at the next level, they also caught the eye of Bob Douglas.

Excerpt from the new book THE BLACK FIVES: THE EPIC STORY OF BASKETBALL’S FORGOTTEN ERA by Claude Johnson published by Abrams Press

Text copyright © 2022 Claude Johnson