Former President Barack Obama awarded Bill Russell with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011, describing the NBA legend as “someone who stood up for the rights and dignity of all men.”

Beyond the 11 championship rings, the 12 All-Star appearances and the five MVP trophies, Russell is a groundbreaking force, a source of unending strength and courage. And his fearlessness has extended way past the hardwood.

Russell grew up in West Monroe, LA, during the middle of the Great Depression. He became used to rampant racism, watching his parents deal with it on a daily basis. After living amongst hate for too long, Bill’s father, Charles, moved the family to Oakland, CA in 1944. Bill’s mother, Katie, passed away in 1946.

“My father was my hero,” Russell said in an interview for NBA TV. “Because when my mother got sick, and she knew she was dying, she asked him to promise her that he would send her boys to college.

“We buried her in Louisiana. She had five sisters. They were deciding who was going to take me and who was going to take my brother. And my father said ‘I’m going to take them both back to California with me.’ They said that men can’t raise kids. He said, ‘I promised their mother I would try.’ …He sacrificed so he could be home every night to be a good parent. I was never afraid because I knew that he loved me and he never let me down.”

The strength that Bill witnessed in his parents carried him throughout the rest of his life, because the racism didn’t stop even when he became one of the best ballplayers of all time.

Despite winning two NCAA championships and racking up national collegiate honors including All-America selections and NCAA tournament MOP, there was a possibility Russell was going to stop playing basketball.

“St. Louis was overwhelmingly racist,” Russell said on NBA TV. “If I had gotten drafted by St. Louis, I wouldn’t have went into the NBA.”

The Hawks were based in St. Louis in 1956 when they selected Russell with the second overall pick. The city, as Russell said, had a serious problem. So when coach Red Auerbach and the Celtics swooped in to trade for Russell, he was glad.

The Celtics were the first NBA team to ever start five African-American players. They were the first franchise to ever draft an African-American, forever etching Chuck Cooper’s name in history. Auerbach didn’t see color, he just saw winning.

But Boston didn’t think like that. During Russell’s playing career, the city repeatedly treated Russell with vitriol and hate.

“I didn’t become aware of Russ’ problems until later,” his former teammate Bob Cousy told ESPN. “Within the unit, I think Russ felt we had his back. But when he walked outside the unit, he’d sit in the lobby and be reading his paper and some white guy would come over and make his speech—’Mr. Russell, I’m your biggest fan, you are the greatest’—and Russ would never look up from his paper. So, Russ felt very strongly, and I don’t blame him, about the issue [of race]. My God, they broke into his home, they defecated on his bed. He went through so much.”

Cousy referenced the time that Russell’s home in Boston was invaded. His bed was defiled with feces and there were racist messages written on his walls.

He delivered winning to the city of Boston (11 championships in 13 years) and they showed him their true colors.

“Bill Russell got tagged with being antiwhite and rude and everything else,” former teammate Tommy Heinsohn said to Boston Magazine. “But all he really wanted to do was be recognized as an individual. He had been slighted several times, and he was smart enough to recognize it.”

Russell’s prime on the court synced up with the civil rights movements of the 1960s. And he used his platform as one of the country’s premier athletes to shine light on the injustices that he saw his peers suffering through.

“It is the first time in four centuries that the American Negro can create his own history,” Russell penned in the 60s. “To be part of this is one of the most significant things that can happen.”

When a restaurant in Lexington, Kentucky refused to seat Russell and his black teammates in 1961, they boycotted the ensuing game. Russell walked in the 1963 March on Washington for civil rights and frequently called out ways in which he perceived the NBA to be limiting its population of African-American players. He used to reference Jackie Robinson and a desire to continue the work that he started in the 1940s.

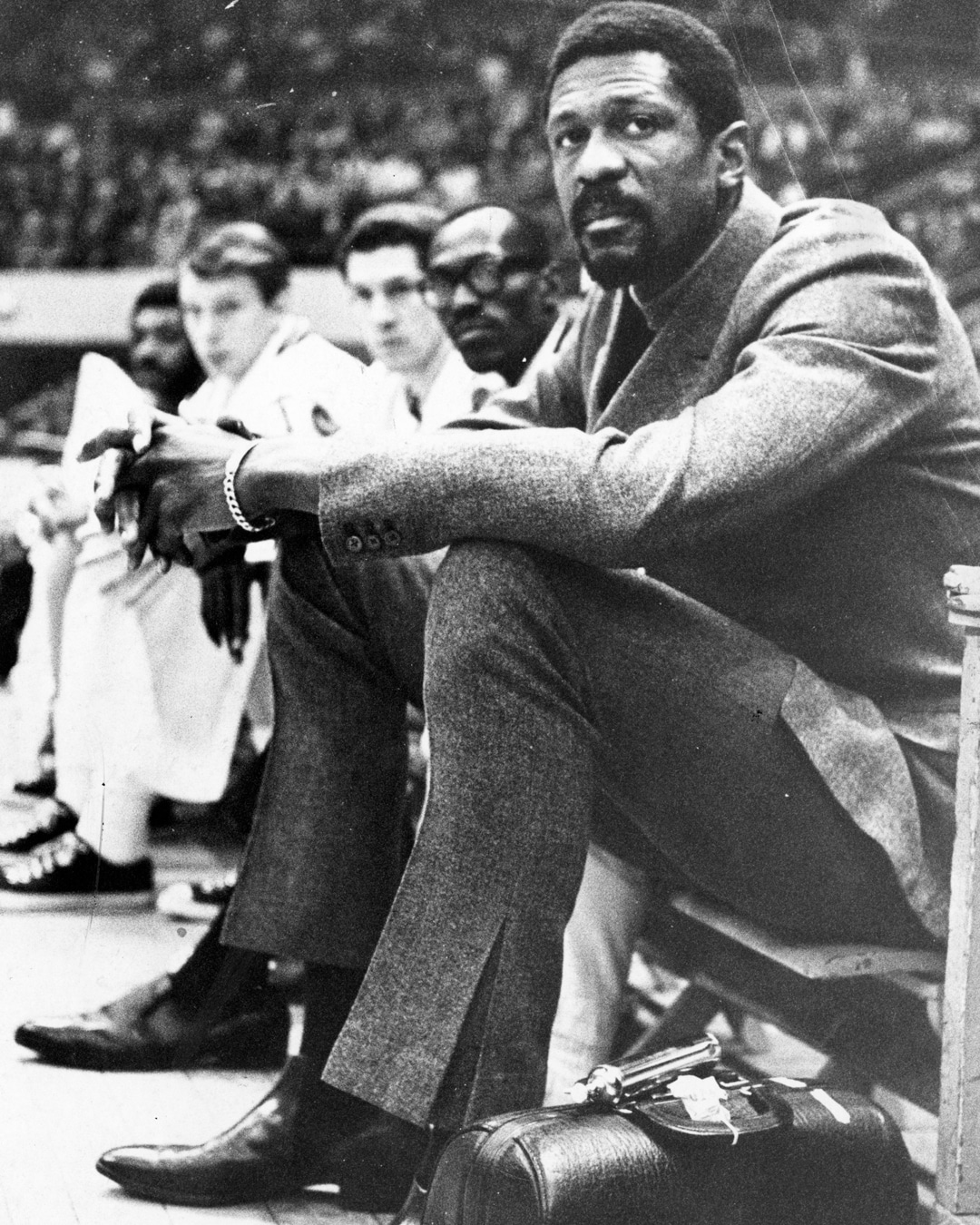

In the same way that Robinson was a pioneer for baseball, Russell eventually became a pioneer for basketball. The Celtics named him head coach in 1966, as he became the first African-American head coach in NBA history. And the best part was that he was still playing. And then the icing on the cake was that Russell led his team to two titles as a player-coach. But the haters couldn’t get out of their feelings.

“I remember at the press conference,” Russell told The New York Times, “probably the second or third question one of the Boston reporters asked me, ‘Can you coach the white guys without being prejudiced?’ Now, I didn’t recall anybody asking a white coach if he could coach the black guys without being prejudiced. All I said was, ‘Yeah.’ ”

The city of Boston finally paid their respects to Russell in 2013, 44 years after he capped off one of the greatest and most ingenious careers the NBA ever saw. They gave him a statue at Boston City Hall Plaza, praising a daring, innovative and unapologetic hero.

—

Max Resetar is an Associate Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

Photos via Getty.