“It must be the shoes.”

To people of a certain age—and Spike Lee, who first uttered those words in 1988, falls squarely into that range—that statement attempted to explain the unexplainable, to justify the unjustifiable, to help us make sense of something that made as much sense as JR Smith on the court during an NBA Finals: the perfect storm and violent ascendance of Michael Jordan as demigod.

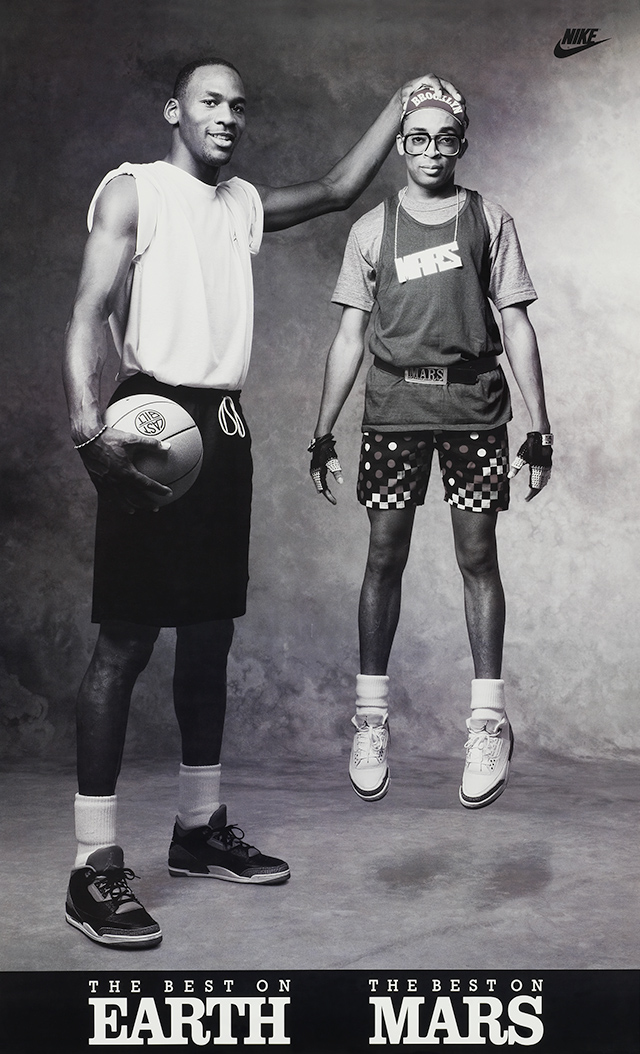

Mike just seemed more fearless and cunning than every other player, a true two-way superstar in an era not known for them. And by the time Spike Lee’s alter ego—Mars Blackmon—showed up on the scene, in an Air Jordan III commercial, control of the NBA was Jordan’s and Jordan’s alone. Nike, which was really just getting its sea legs in basketball, had an idea for a series of absurdist advertisements to help sell Air Jordans, which was as difficult, at the time, as selling crack to crackheads: it must not be the player, it’s his shoes, they offered. And that’s where Lee as Mars Blackmon entered the picture, as both a TV pitchman and an important part of sneaker culture. A Bed-Stuy-dwelling, basketball court hanger-on, Mars shadowed and peppered Michael Jordan with questions in an attempt to uncover the truth. We were never under any illusion that Mars himself had game, but Spike Lee made him cool because, as oversized as Mars’ personality was, he was relatable. Mars was obsessed with Michael Jordan and basketball shoes. “Money, it’s got to be the shoes,” he insisted, and us sneaker obsessives silently nodded and counted our cash.

After a few years, the company finally realized that it could use any two-legged person to sell its kicks, Mars eventually took an extended vacation—once Little Richard popped up as a genie, it was time to ride the pine for a while. Nike then made a regrettably wretched Looney Tunes detour, Steve Martin was featured in an Air Jordan commercial and Harold Miner’s presence soured another.

Luckily, Spike had been busy elsewhere: In ’97, he created Jesus Shuttlesworth, the main character in He Got Game, which was basically The Stephon Marbury Story starring Ray Allen. During filming, Lee, who took an early liking to SLAM, invited me out to Coney Island for an overnight shoot, where Ray Allen play-confronted me about something misguided and insane I had written about him in the magazine. (In those days, that was a somewhat regular occurrence.) Afterward, I had a 3 a.m. dinner with Spike, Ray and the film’s special adviser Earl Monroe and got to watch some NBA players goof around at The Garden, the famed projects court that spawned the Marburys, without the fear of being slain.

That’s when SLAM’s history with Lee became complicated, as we attempted a collabo as ill-fated as the Knicks and the triangle offense. The short version: We’d planned on putting a crucified Shuttlesworth on the magazine’s April ’98 cover and treat the story as if he were a real player. A rather elaborate April Fools’ joke, even though the magazine came out at the beginning of March. Not to sound like a human cave drawing, but that was before the internet spawned countless blogs that would have instantly revealed the truth and ridiculed us. (Back then we pretty much had the market cornered on sports ridicule.) In ’98, we basically only had to dodge USA Today, AOL’s landing page and, to a lesser extent, Stanley Harris, then SLAM’s owner.

Lee’s team agreed that we would have the story first, and we would continue the ruse until after we’d gone on sale. We were looking forward to a great reveal, but were truthfully way more excited about the idea of a guy nailed to a cross on our cover. In retrospect it’s not hard to fathom why none of us ended up at Sports Illustrated. Then someone sent photos of Ray, in character, to USA Today and so, with the element of surprise ruined, we pulled out. Lee called me, flabbergasted that we were not going forward with it and I responded that we had not signed up to do a promotional cover for a soon-to-be released film. He probably felt that I was being foolish and hopelessly naïve to think the news would hold, but, after a few volleys back and forth, we left it on good terms. I was a rube and we were both comfortable with that assessment. Our paths crossed numerous times in the intervening years and Spike was always complimentary of SLAM and KICKS. And he always had fresh gear on.

In October, ’06, Nike introduced the Spiz’ike to commemorate their relationship. It was an Air Jordan 3-4-5-6 combo and the shoe quickly became a staple for Nike, cementing Lee’s place as the third most important person in Air Jordans history after Mike and designer Tinker Hatfield. Incidentally, that also places him in the top 10 of most important non-players in sneaker culture, miles ahead of Lil’ Penny, and a long-overdue member of the KICKS Hall of Fame.

Epilogue: Several weeks ago, a pair of my original Carmine Red Air Jordan VIs lost their brave battle with Father Time, as the heel literally opened up and projectile vomited foam all over my apartment. As I swept up the remnants from my floor, I was reminded of Mars, Mike and Spike, who is also old enough to have worn the originals. Those kicks lasted me 24 years. So Mars was correct all along: It was, in fact, the shoes.

Tony Gervino is a former Editor-in-Chief of SLAM and the current Editor-in-Chief of Billboard. Follow him on Twitter @microtony.

Catch up on the entire KICKS Hall of Fame here.