You Don’t Know Jack: Here’s a Look Back on Jackie Robinson’s Basketball Career at UCLA

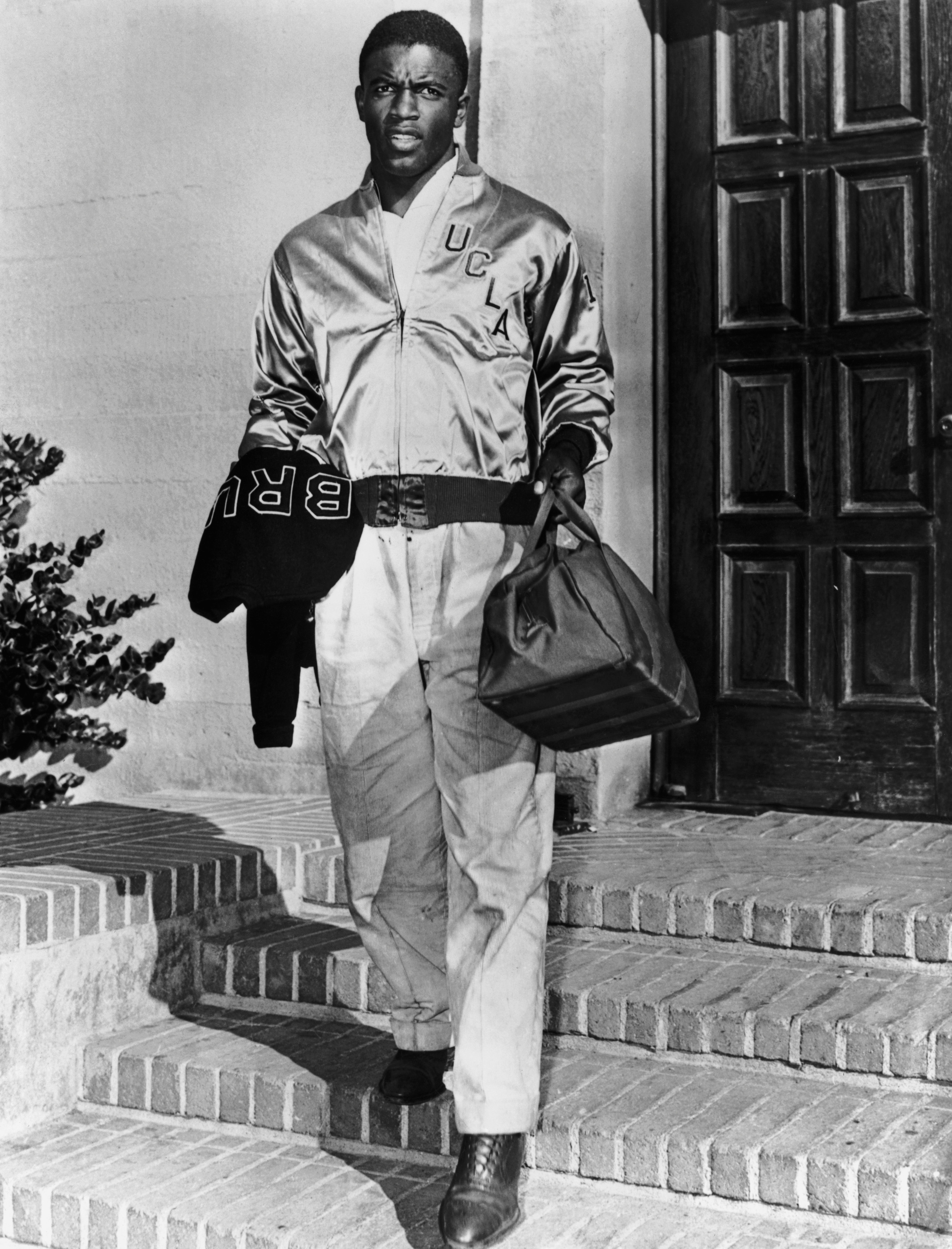

On grass, dirt or on hardwood, there was only one Jackie Robinson. And well before he stepped on to Ebbets Field as a Brooklyn Dodger and broke the color line in Major League Baseball on April 15, 1947, Robinson had made some multi-sport—including basketball—history in college.

In 1941, Robinson, who lettered in track, baseball, basketball and football at UCLA (the only Bruin to ever letter in four varsity sports), played in the annual NFL-College All-Star game. Dick Plasman of the Chicago Bears called Jackie the fastest man he’d ever seen in a uniform after he ran roughshod over the NFL champions. “He’s the fastest thing I’ve ever seen,” said Wilbur Johns, Jackie’s basketball coach at UCLA.

What’s wild is that Johns insisted that if Jackie hadn’t played football, or, well, baseball, he would have been the greatest basketball player ever.

“His timing was perfect. His rhythm was unmatched. He had the valuable faculty of being able to relax at the proper time,” said Johns in the 1950 biographical film, The Jackie Robinson Story.

Johns, who moved from head coach to Athletic Director at UCLA and helped bring John Wooden on board to replace him, did not exactly have Wooden-like success as a coach before Robinson’s arrival. UCLA hadn’t won a Pacific Coast Conference game in more than two years when Jackie arrived on the team in 1939. The hype was real, but he was a one-man show, a great player on a bad team. With Robinson, the Bruins went 5-19 in the PCC, but that was a big improvement. And it didn’t matter, anyway; people came to see Jackie.

Grainy newsreel footage memorialized Jackie’s Red Grange meets Barry Sanders football exploits on film, but his basketball exploits are largely folklore. California coach Nibs Price

once called Robinson the best in the country. The Pittsburgh Courier lauded Jackie’s handle, calling it glue-fingered. One story went that he faked three guys out to elude a triple-team and score. Armed with a deadly outside shot and quick hands, Jackie could dominate all facets of the game. His strength allowed him to play forward despite standing just 5-11, and his sheer athleticism and unicorn speed left all who saw him spellbound. He also had that inimitable Jackie Robinson fire, its embers stoked no matter the type of ball in his gifted hands.

It’s often rendered a mere footnote in the epic saga of Jackie Robinson. Weeks after he led the Montreal Royals, the Brooklyn Dodgers International League farm club, to victory in the 1946 Little World Series, Jackie Robinson bested the NBA’s first superstar. For real. Here’s what the the basketball portion of arguably the greatest athletic career of the 20th century looked like, in three brief chapters.

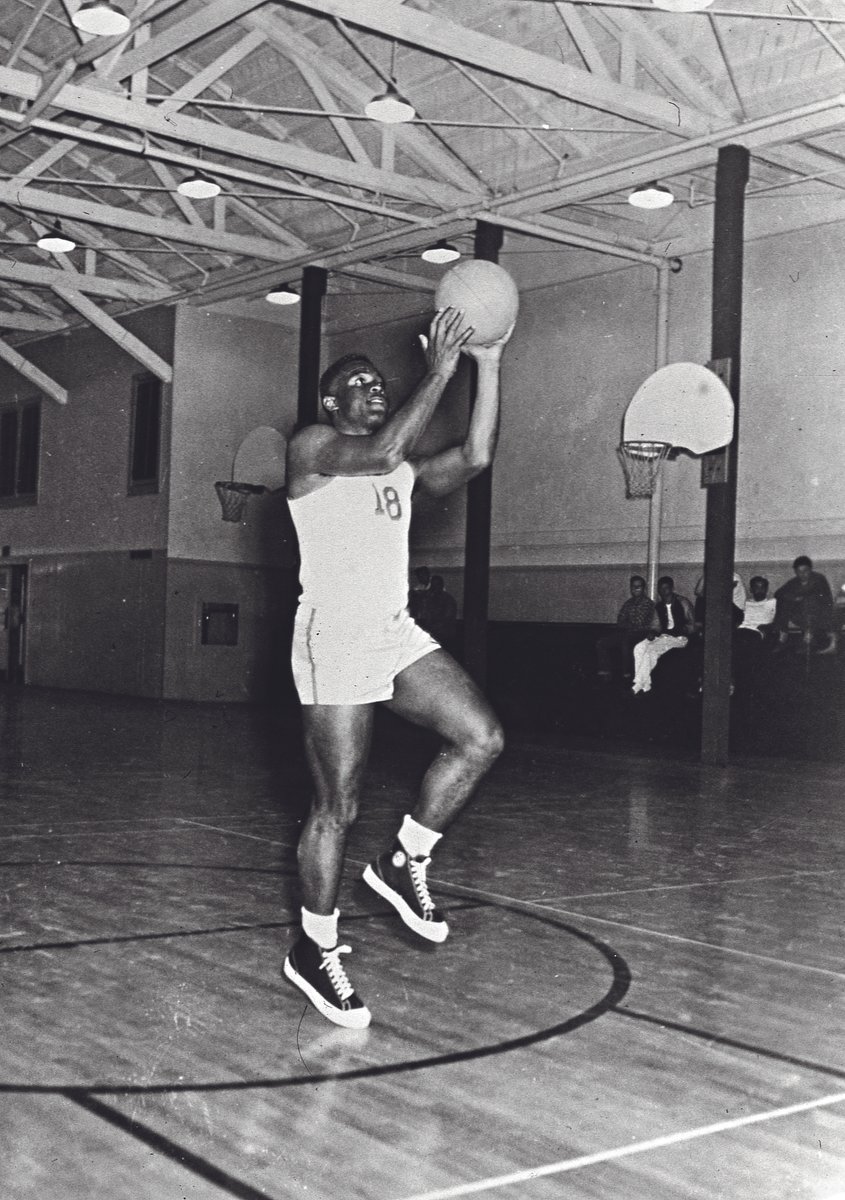

THE UCLA DAYS

Cal and UCLA are tied with the clock winding down. UCLA’s best player has the ball in his hands and eyes the rim. With the grace of a dancer, he pivots off his left foot and lets a vaunted skyhook go from the free-throw line. Pandemonium turns to silence at Berkeley—the deflating silence only a basketball assassin can elicit. It reads like a play from the Lew Alcindor era, but it’s all Jackie Robinson. Just like that, UCLA’s 30-game conference losing streak was over.

“Jackie could uncannily rise to the occasion,” Wilbur Johns told Arthur Mann, author of The Jackie Robinson Story. “His [handle] was breathtaking. His speed, passing, and deception sent fans wild with joy.”

UCLA seldom won, but eyes were perpetually transfixed on Robinson, who played on the team as a junior (’39-40) and senior (’40-41) after starring in the same four sports during his two years

at Pasadena Junior College. When Jackie scored a career-high 23 at Stanford in his first conference game, the opposing crowd showered him with cheers.

When Robinson fouled out in his Palo Alto finale the next season, Stanford captain Don Williams met him at the visiting bench with a handshake. A packed house gifted him a more rousing ovation than in his debut.

Stanford guard Ken Davidson called Jackie the best player in the conference. Robinson edged USC All-American Ralph Vaughn, feted as basketball’s golden boy on the cover of Life magazine, for the first of his back-to-back PCC Southern Division scoring titles.

Johns said Jackie Robinson taught everybody the true meaning of team but was still the quintessential alpha dog who came through in big moments. He dropped 18 and hit the go-ahead basket to again beat Cal at home. When his floater with 15 seconds left seemed to win another game against Stanford, a ballistic Westwood fell silent when Williams tied the game. Robinson drew attention and set up the winning hoop in overtime.

Jackie saved his best antics for USF, the legendary Bill Russell’s future alma mater, as a senior in 1941. When Los Angeles battled San Francisco, nobody cared that it was a non-conference game. UCLA was down 4 with less than a minute remaining when Robinson followed up a Bruins bucket with an interception of USF’s inbounds pass and then banged in a runner to force overtime. UCLA fell behind in OT, but Robinson’s Bruins fought back. The game was deadlocked at 53. No video exists. For an approximate reenactment, Google “Kawhi beats Sixers.” It was Jackie’s rock with the game on the line. He darted up the court as time fettered away. Just as the final gun sounded, a high-arcing one-hander left Jackie’s fingertips. The crowd watched in collective awe as the ball caromed off the back of the rim and bounded straight into the air. For just a moment, time stood still. It seemed like all of Westwood rushed the court to mob Robinson just as the ball sunk back through the iron and tickled the bottom of the twine.

All in all, Jackie averaged 12.4 ppg and 11.1 ppg, respectively, in his two seasons at UCLA, earning All-PCC Southern Division in 1940. Robinson scored about 40 percent of UCLA’s points, which is akin to what Wilt Chamberlain did for the Philadelphia Warriors in his record-setting ’61-62 season.

The PROFESSIONAL HOOPER DAYS

After leaving UCLA and briefly working for the National Youth Administration, Robinson was drafted into the US Army in 1942. He never saw combat for a variety of reasons, including alleged racism he encountered, but Robinson was in the Army until November of 1944. The war, along with the racism that kept professional sports effectively closed to African-Americans, paused his career in all sports.

But by 1946, with baseball and football still on the table, the Atlanta Daily World said that Robinson was destined for basketball greatness. When the Los Angeles Red Devils, an independent basketball team not affiliated with any leagues, called, Jackie answered. Owner and coach Jack Duddy had ambitions to join the National Basketball League and bring professional basketball to the West Coast. As ever, the pro game was driven by superstars. In 1946, there were few bigger names than Pasadena’s own Jackie Robinson, even if he hadn’t played competitively in five years.

The Red Devils started like gangbusters with four wins, the first two over the Sheboygan Red Skins. Jackie scored 10 points in his pro debut. In the second of a back-to-back, Robinson hit for a season-high 18 points. When 6-7 center Ed Danker sent the 5-11 Robinson tumbling to the floor, everyone in Olympic Auditorium leapt to their feet as Robinson somehow sunk a 15-footer while sprawled prone on his back. The California Eagle proclaimed a glimpse of Jackie Robinson in action was worth the price of admission:

“Speed is a wonderful thing, and Jackie is a streak of greased lightning. He’s great in baseball and equally great on the [court].”

The legendary New York Renaissance flew cross-country to play the Red Devils, foreshadowing how the jet age changed sports in post-war America. The Rens had won the 1939 World Professional Basketball Championship and helped lay the foundations of pro basketball. Legendary center Nat “Sweetwater” Clifton, who integrated the Knicks, didn’t even crack their top five. And yet…Jackie’s Red Devils beat them twice at Olympic Auditorium.

The showdown: GEORGE MIKAN VS. JACKIE ROBINSON

They don’t slap the name Mr. Basketball on you for nothing. The Red Devils’ biggest test was George Mikan’s Chicago Gears of the NBL. When Mikan arrived at Madison Square Garden, the marquee didn’t mention his team, simply “Geo Mikan vs. New York Knicks.” Mikan and Jackie were the two biggest stars playing pro basketball in 1946, even if one was just passing through.

It looked like Jackie was finally showing signs of fatigue when he scored just 4 points in the Red Devils’ only loss to NBL competition. His first son was born earlier that week. The next night, Jackie exacted swift revenge. When jostling got out of hand, he had to be restrained from fighting 6-3 Bob Calihan. Mikan’s 22 outshined Robinson’s team-high 13 points, but Jackie’s squad avenged the 59-56 loss with a 47-46 win over the Gears, who later beat the Rochester Royals in the NBL Finals.

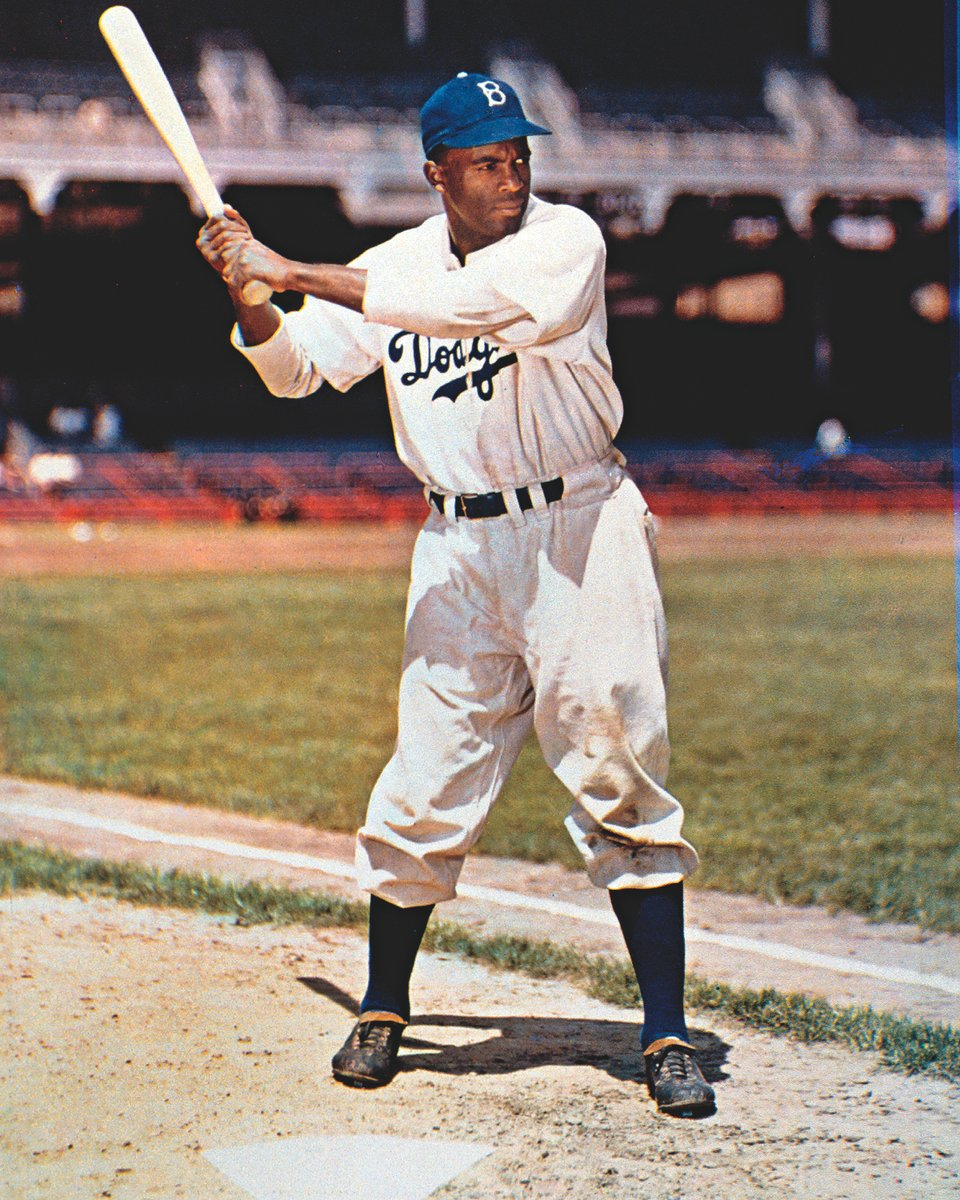

Headlines about Robinson’s future with Brooklyn often dwarfed fleeting references to Jackie throwing down with the best ballers in the world. The biggest question on America’s mind for the year 1947, according to the Associated Press, was Jackie’s future with the Dodgers. Beating Mikan head-to-head was relegated to a line item.

Jackie’s brief dalliance with pro basketball foreshadowed the impact of his arrival in Brooklyn. His swan song in hoops was against a Del Webb-sponsored pro team in Tempe, AZ, at Union High School when Arizona schools were still segregated. It was likely Arizona’s first integrated sporting event. The Red Devils, who had multiple Black and white players, went 13-3 during Robinson’s season (the only one the franchise played).

What if…

Could Jackie have really been an elite NBA player? Consider that his stint as a pro was sandwiched in between the year he proved ready for Major League Baseball and his actual Rookie of the Year campaign. Jackie still averaged 10 ppg, which is extra impressive considering there was no shot clock, no three-pointers, goaltending was legal and teams rarely scored more than 45 points.

Sounds like he could have made history on the hardwood if he didn’t get busy changing the world as a Dodger. We’ll never know what could have been.

Photos via Getty Images.