For the very first time, Merl Code is finally ready to speak his truth. It’s been three years since he and his co-defendants, Christian Dawkins and Jim Gatto, were found guilty of fraud, conspiracy and bribery back in 2019 after the FBI conducted an investigation into the inner workings of college basketball recruiting two years prior. Code, who will soon serve prison time, says on our hour-long Zoom call in February that he’s ready to share his story with the world. And, in his new memoir, Black Market: An Insider’s Journey Into the High-Stakes World of College Basketball, he holds nothing back.

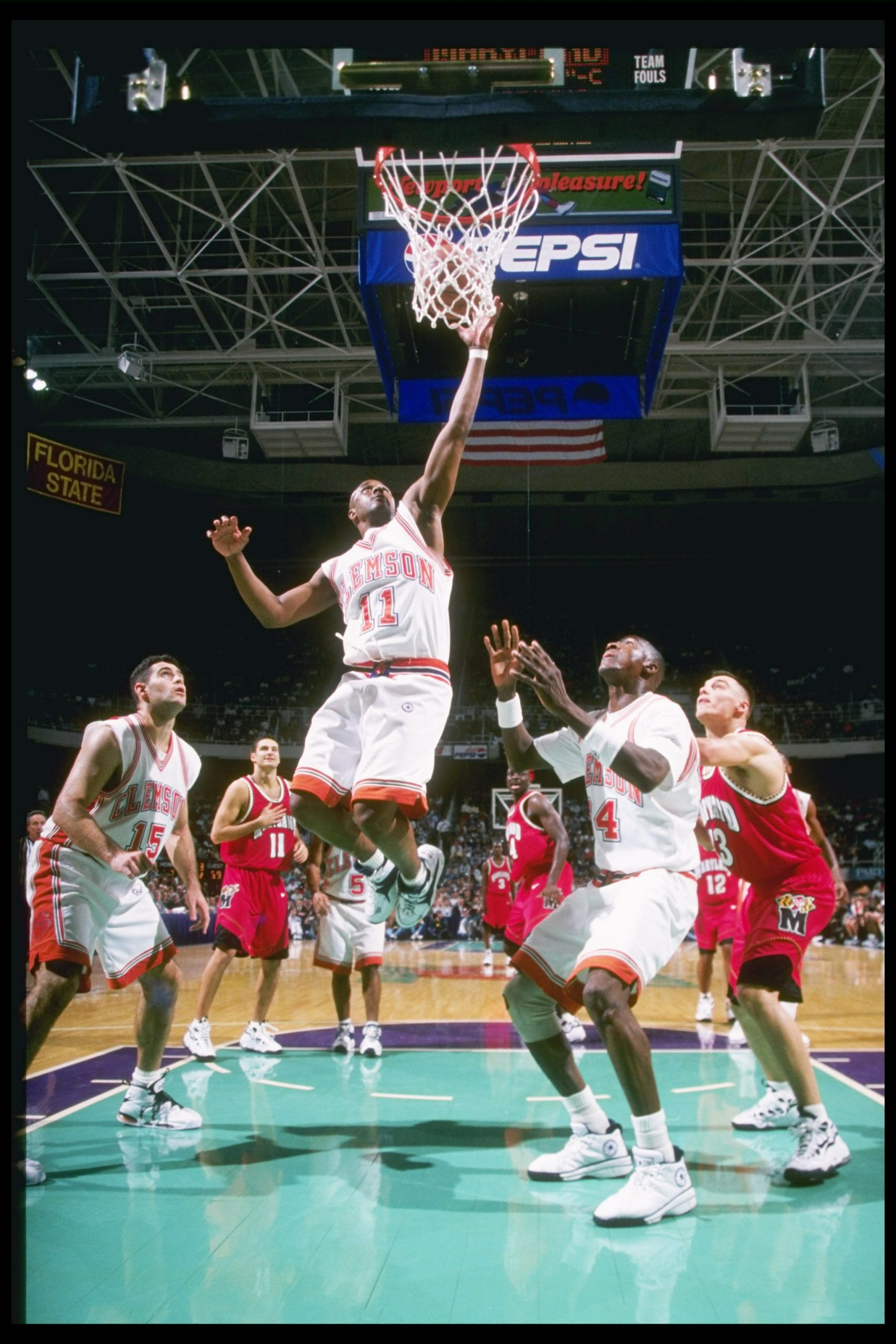

Black Market, out now, masterfully reveals how the business side of college athletics actually operates—all from the perspective of someone who not only was a college athlete himself (Code played four years at Clemson from ’93-97) but later as a director and consultant for some of the biggest sports brands in the world. Code gives eye-opening, first-hand accounts of what exactly went down, from the families and players he formed relationships with to the ways in which he did the job he was “instructed to do.” When tasked with helping evaluate promising NBA talent, Code details how in order to evaluate rookies coming into the League, he needed to be tapped into the high school basketball circuit.

“I had to know what kids in my markets had NBA potential, kids who might spend one or two years on a college campus before being a first-round draft pick,” he explains. “…If a high school kid in my region had pro potential, I started showering him with the flyest sneakers and gear at least once a month.”

This was the case for college athletes, too. “If there was a college kid in my region that had some first-round draft potential, I was calling up his coaches to tell them I was sending him a side package…”

After years of media coverage on the high profile investigation, all stories that featured no quotes from Code himself, Black Market allows him the opportunity to finally own his narrative. And he brings the receipts, too. The book includes an internal email, text messages and even excerpts from the wire-tapped phone calls, including some with college coaches.

“Being able to put some of those transcribed situations into the book that says, wait a minute, these are actual conversations, and this is what actually happened. I wanted to make sure that I could now start creating the true narrative versus what the media has portrayed the past four or five years.”

While he watched coaches, athletic directors, and others directly profit off and “exploit” hoopers, many of whom are Black, Code says he saw players with families in need, whom he believed should get some sort of benefit out of the system. He says necessities included anything from groceries and winter coats to mortgage and rent payments, and he says he doesn’t regret anything he did to help them, either.

“I was mad, [but] I’m not mad anymore. I’m determined to make sure that I do everything I can to touch as many people as I can with my story [and] with the truth. That’s why if you notice at the beginning [of the book], it makes people uncomfortable. I’m not sugarcoating, I’m not doing it anymore,” he says. “So all of the platforms and all the opportunities I have to speak [the] truth, we’re gonna do it. And if that causes people to be uneasy, I don’t care. They made me uneasy for a very long time. So it’s my turn.”

He had a lot more to say, too. In his own words, here are Code’s thoughts on the NIL era, what he hopes people will get out of reading this book and where his relationship with basketball stands today.

SLAM: How did the idea for the memoir come about? That moment, when you just said, You know what, I’m going to speak my truth.

Merl Code: Oddly enough, that was never my idea…A good friend of mine, who was like a brother to me, Eric, he was a former hooper that played at Morgan State…When all the things were happening with me in terms of the arrest and the court case and what have you, he called and was like, Hey, man, we need to talk. And I said, OK, what’s up? He said, You need to write a book. I said, Eric, I don’t know anything about writing a book. I can write, but my writing is typically reserved for emails. So, he convinced me that this was kind of the path I should take. And I said, Well, why? I was being short-sighted in my thought process, and he basically said, Listen, man, you got to take the first step to start telling your story. My initial thought was that it would be done, you know, this way—through interviews, whether it be radio or television. And he said, ‘Listen, all of the things that you have to say, and all the things you have experienced, [it] can’t be captured in a five-minute radio interview, or a 10-minute Zoom call. So, unless somebody [who] knows you and knows your story is willing to say, Here’s a movie deal, we have to start building the layers of your story to really give the public a true sense of who you are as a person and the true narrative that you want to tell.’

SLAM: Did you feel like you were fully ready to tell your story?

MC: No, because I was angry. I had to get past my anger so that it wasn’t a venomous story. I didn’t want it to be a vindictive diatribe, right? I wanted it to be a heartfelt but true account of what happens in this space, my personal experiences [and] my personal thoughts and feelings. If anybody has had the opportunity to read it, I think that comes across in a tenor and tone of voice. And listen, I’m not here to bash anybody. I even leave situations and names out, because what good does it serve? What purpose? Because it’s happened to me, it should happen to you? No, if that was the case, I could have taken a stand and told on any and everybody that I knew in the business. I’m not built that way. Whatever you gonna do to me, I’m gonna deal with, but what I’m not gonna do is put other Black men in harm’s way, because you guys can’t control me. And when white folks can’t control something, they criminalize it…I’m a grown man.

SLAM: Can you walk us through the writing process and what it was like to revisit those moments, including your own experience as a college athlete at Clemson and hearing that some of your teammates were getting paid.

MC: It was cathartic, in a sense. It was an opportunity for me to kind of talk about things that I’ve never spoken about before. I’ve joked about them or been in the conversation with my teammates and we’ve joked about those things in the past. Because it’s a fraternal society. You don’t talk about what happened in the locker room or what happened on the road trip. We got together at a reunion, or met up at a championship game or somebody was in town and we all went to grab dinner, we laugh and joke about what happened on this particular day, at this particular practice.

But to talk about it in a public forum so that others who don’t get the experience of being a college athlete, who don’t understand the time commitment, who don’t understand that it really is a job. It is a full-time job. I think the part that I really wanted to resonate was like, you guys keep talking about all these NCAA rules—well, shit, we were signing documents lying because they were forcing us to, saying that we were only practicing or doing anything basketball related [for] 20 hours a week. That [was] absolute garbage…Everybody’s up in arms about NCAA rules and violations. And it’s a farce. It really is. It’s a farce. But again, you charged me with a federal crime, but there’s no federal legislation. And now those same kids can make money and accept the same things that happened in my situation, but there’s been no legislation to change? So how is it then a federal crime? When you get to a place where you really realize, OK, you were trying to make an example out of me. But it backfired. So I’ll take my punishment, but these young men and women will benefit going forward.

SLAM: How long did it take for the book to come together?

MC: About 16 to 17 months. There were a lot of gaps in there after the proposal—really trying to formulate thoughts and where the book was going to go, and how much are we going to put in because we have so much stuff. I mean, we probably have two more books full of information that just wasn’t conducive to this project. We didn’t want to produce an encyclopedia, so we wanted to keep it streamlined. But, there are other relevant stories that we just didn’t touch in terms of the experiences and things that I’ve dealt with. So that could be another project down the line or be something that turns into a podcast or a television series or movie…That would be great if those things happen, but that wasn’t the purpose for this.

SLAM: Was there a moment during the writing process when you realized the gravity or the magnitude of a certain situation and said to yourself, Wow, that actually did happen!

MC: I mean, sitting in a courtroom and hearing a judge say, You’re not gonna talk about poor Black kids in my courtroom, was kind of like a, ‘What the f***?’ [moment]. Excuse my language.

And then when you realize, wait a minute, he’s protecting the universities because he won’t allow any of the contractual relationships, nor the coaches to testify, nor the athletic directors, nor any of their wiretapped phone calls. Like, you’re not letting any of this information in? So, all the jury gets to hear is the government’s narrative that I am corrupt. Wow.

SLAM: You’ve said there were so many other things you could have included. How did you decide what to include and what to keep out?

MC: It was a collective [decision] in that regard. Certain things, from a legal perspective, could cause us some liability issues. Even though it’s the truth, but you can’t prove it. Well, shit, it was 20 years ago, how could I? There were certain things for me, [saying] a name didn’t really add to the story. And all it would do is damage that particular person and his family, whether he’s dead or alive. That kind of stuff. And so, [I] kind of withdrew and said, Yeah, that doesn’t really make sense to put that man’s name. He’s got children, you know? That’s why I wanted to make sure that the tenor and tone was not one of vindication. It is one of an actual true account of what happens in this space, the things these kids deal with, and if you notice, I even applaud some of the families. Hey, man, you should have gotten more. I know what I did to try to help you. I know what the schools did to try to help you, and I’m OK with it. You should have gotten more, because of the kind of money that you helped generate for that particular coaching staff, that athletic director, because at the end of the day, sports pays for these universities to survive. They can’t survive on sheer tuition. If they don’t have football and basketball, they can’t survive. They pay teacher salaries, they build new English and Science buildings, they do all that stuff off the backs of these young men and women. And when the pandemic hit, it was really brought to the forefront in terms of how important sports was.

SLAM: On that note, what are your thoughts on the passing of the NIL laws?

MC: People don’t understand the concept. [They’re like] Oh, but it’s an NIL deal. Yeah, but I still have to ask you, white folks, Can I use my name? Can I use my image? Can I use my likeness? Can I use my ability to earn money for myself? Again, people keep passing by this like that’s OK. And it’s not. If we really live in a capitalist society, every young man and woman should be able to go out and make as much money as they possibly can with their abilities. Whatever that looks like. You don’t cap the white sports…So let’s really get down to the nuts and bolts of what this is, because these are the revenue-generating sports [that] keep these universities alive. Because if they don’t win, they don’t bring in sponsorship dollars. They don’t get the same kind of TV revenue. The boosters don’t give as much money. It’s all predicated on winning, and you don’t win without these young Black men and Black women. You don’t.

So, until we really get to a place where people are uncomfortable talking about this conversation—because I’m past the point of trying to mince words—and until others get to that same place, it’s not gonna change.

SLAM: Everyone is saying that this book is going to turn the college basketball world upside down. What are your thoughts when you hear that?

MC: I don’t know if it’ll do that. I hope that people will see it on a deeper level. This is about the truth. I didn’t put all of the transcripts in because it wasn’t necessary. Because there’s so much more I could have put in there than I did…I’ve been called everything from corrupt to undesirable. You name it, I’ve been called it. For doing my job. And again, these are people who’ve never experienced a space and don’t understand nor care about these kids and their livelihoods and their circumstances. All they care about is, did their team win?

SLAM: What is your relationship with the game today?

MC: It has been tainted. I still love the game. It’s been such a huge, important and critical part of my life that I’d be remiss to say that I’m done with it. I still love the game and will always love the game. I’ve since removed myself from the business of basketball, for the most part. I mean, I still have love for the people that really know me and the people that really confide and still trust in me. I still brought some opportunities to advise them in certain situations or scenarios. It makes me feel good that I’ve built that kind of rapport with people throughout my journey because, again, all I really did try to do is help, whether it was within their rules or not, all I tried to do was help. This was not a personal benefit or gain. I’m not a rich dude by any stretch of imagination. I’m not worried about my lights being cut off, but I ain’t the one with the beach house as my second or third home.

So, I would like to get to a place—and I think this is part of the process for healing some of that for me—I think once I get to the platforms where I can really kind of continue to dialogue about this and once I have this particular space and time in my life behind me, then I think I’ll be able to kind of start putting those pieces back together to get back into some form of being a part of the business side.

Photos via Merl Code and Getty Images.