“My guy. My guy!”

Yes, this is how Kenny Anderson answers his phone when I call on behalf of SLAM. “I’m finishing up at Starbucks with my wife. Let’s talk in 20 minutes.”

“You got it, my guy,” I reply in kind.

The hilarious and always positive Kenny Anderson character you can follow on Twitter (@chibbs_1, though he says he’s on hiatus ’til March…more on that in a bit) is that way in real life, too.

Anderson, the 50-year-old former NBA All-Star who spent 14 years in the L and is now the head coach at NAIA Fisk University in Nashville, really just wants to do good.

“Everything is working out for me the way God planned,” Anderson says when we jump back on the phone after his standard morning Starbucks run. “I’m just here to help others. It’s not about Division I or Division II, just helping. That’s why I took this job. I love that we’re building something.”

Even though I know the ins and outs of his career as well as anyone’s, as Kenny himself says, “The young kids don’t know me too well, but their parents do.”

So let’s review real quick.

Kenny Anderson was, literally, one of the finest prep players ever. The late, great scout Tom Konchalski called him “the greatest high school point guard of all time.”

A rail-thin six-footer who grew up in the LeFrak City housing complex in Queens, Anderson was a four-year phenom at Archbishop Molloy in Queens, leading the Stanners to two CHSAA titles and scoring a then-New-York-state-record 2,621 points in his career. As a senior, the ballhandling wizard averaged 35 ppg on 77 (!!) percent shooting from the floor en route to winning consensus National Player of the Year honors. “Mr. Chibbs,” as his family had called him since he was little, could make shots from outside, slither through the lane and score at the rim or dribble and dime as if defenders were cones. And he did it all with a smile.

“Coming up in New York I had coach Jack Curran at Molloy and my mentor, Vincent Smith [older brother to fellow Molloy product and longtime NBA player, Kenny Smith],” Anderson recalls. “And I really followed the path of those four guys that were right ahead of me—Kenny Smith, Rod Strickland, Mark Jackson and, RIP, my guy Pearl Washington.”

As good as all four of those NYC “point gods” and some others of that era were, Anderson was in a class by himself. The top recruit in the country in the high school class of 1989, he headed to Atlanta for college and starred at Georgia Tech from day one.

As a freshman, Anderson teamed with upper classmen Brian Oliver and Dennis Scott to form “Lethal Weapon 3,” a trio that won the Yellow Jackets the ACC Tournament and reached the Final Four, where they lost an epic semifinal game to the legendary UNLV team that would win the national title two nights later.

Oliver and Scott departed after that season and, though his game was surely NBA-ready, Anderson returned to ATL for his sophomore campaign. “Going hardship” after just one season of college basketball was hardly ever done at the time. Anderson labored to carry the weight without his great teammates from the year before, at one point losing hair due to the stress of leading the team and the pending decision about turning pro. Struggles or not, Anderson still averaged 25.9 ppg that season (alongside 5.7 rpg, 5.6 apg and 3 spg) and led Tech to the second round of the tournament. And, sure enough, he did turn pro, quickly getting scooped up by the New Jersey Nets with the second pick.

To this NYC-hoops-obsessed fan, it felt like a fairy tale, seeing Kenny paired with Derrick Coleman and Drazen Petrovic on a super-fresh Nets squad that played just over the river in New Jersey. Between injuries, the untimely death of Draz and endless front-office/ownership squabbles, however, those Nets never quite fulfilled their promise.

Maybe Kenny didn’t fulfill his individual promise all the way either, though in retrospect it’s pretty easy to attribute that to his playing for shaky coaches at shaky franchises, and frankly, a God-given body that was not exactly built for the rigors of an 82-game NBA season. Anderson still earned the start in the ’94 All-Star Game and parlayed his time in the Swamp into a seven-year, $49 million free agent contract with the Portland Trail Blazers in 1996, theoretically setting him up for life. All told, Anderson spent 14 seasons in the NBA (making the playoffs six times), finishing his career with averages of 13 points and six assists in 30 minutes per game. A real-ass career, in other words. He also made approximately $63 million in pre-tax salary.

The money was enough to achieve Anderson’s main life goal—to take care of his single mother, Joan. It also brought on all sorts of off-court drama; fathering seven children with five different women ate away at the funds and led to a bankruptcy declaration in 2005. This, combined with Joan’s passing the same year, made for some hard post-NBA years.

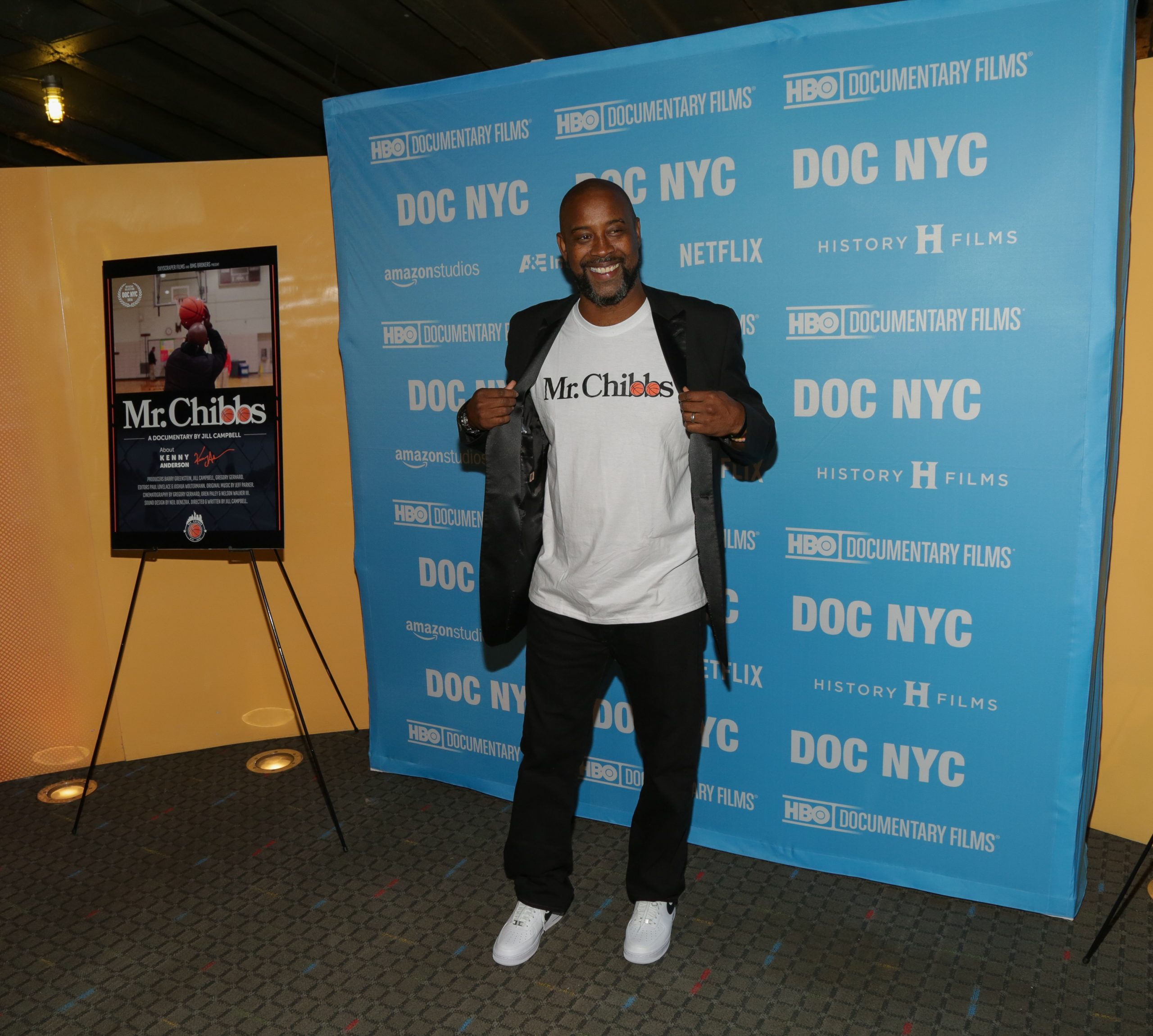

Eventually, Anderson settled in South Florida with his new wife, Natasha, regrouped and got into coaching, first at the AAU and then high school level. He was also the subject of a 2017 documentary, Mr. Chibbs: Basketball is Easy, Life is Hard, that expounds on that tagline, a phrase Kenny utters frequently and knowingly. (Full disclosure: I proudly donated to the Kickstarter to help get that thing made.)

In 2018, then-Fisk President Kevin Rome reached out. “The president of the school went to Morehouse College in Atlanta, so he knew me from my days at Georgia Tech,” Anderson recalls. “He brought me in. I knew the school needed some work in the athletic program. I thought about my high school coach, Jack Curran, and that’s what I wanted to do. Start low, give these young men something to reach for.”

Fisk is a historically Black university (less than 1,000 students) in Nashville that was established in 1866 and is far more known for its academics than its athletics. The list of notable Fisk alums is jaw-dropping, featuring such historical figures as W.E.B. DuBois, John Hope Franklin, Nikki Giovanni and Congressman John Lewis, among many others. No famous hoopers, though. The big program in Nashville is Vanderbilt of the Power 5 SEC, where Anderson’s contemporary, Jerry Stackhouse, is head men’s basketball coach. “We can’t compete with them, of course, but I am hoping we can get a scrimmage with them in the future,” Kenny says.

Anderson succeeded Dr. Larry Glover, who is now Fisk’s Athletic Director, as head coach for the 2018-19 season. Glover was thrilled. “The president brought it to my attention that he had spoken to Kenny about coaching here,” Glover says. “We thought it was a good idea. He didn’t have the college coaching résumé, but the playing experience was enough to compensate for that over the long run. For ex-players who have played for a lot of coaches, it’s kind of innate. And when you play at the level he has played, you know the game inside and out. We thought it was a win for basketball and athletics and the school itself.”

Mentor Vincent Smith, who met Kenny when he was 9 years old and shepherded him through his amateur basketball career, is still the man Anderson turns to for advice. Smith encouraged Anderson to take the Fisk job and thinks he has the makings of a great coach. “Kenny always had a high basketball IQ,” Smith says from his home in California. “He wasn’t the guy who made it because he had a 40-inch vertical leap. He knew how to change speeds, he was the master of the midrange game and he always knew how to run a team and get people involved. Point guards know every position on the floor. The coach and the point guard have to be connected and on the same page. We knew he could be a good coach.”

All that said, a variety of unexpected hurdles make it feel like Anderson’s college coaching career is only starting in earnest this fall. In that first 2018-19 season, coaching players he didn’t recruit, Anderson’s Bulldogs went 8-17 and Chibbs was struggling. “I wasn’t eating right,” he says. “I was stressed out. Guys weren’t taking it serious enough. It was a lot of stress on me, I realized.”

On February 23, 2019, just days after the season ended, Anderson suffered a stroke while at his house in Florida. Only 48 years old at the time, he might have died were it not for his scared dog (the Instagram-famous Caleb) and daughter, Tiana, who realized what was happening. Tiana called Natasha, who got home and got Kenny to the hospital. Doctors saved his life, but months of mental and physical rehabilitation followed.

Anderson recovered pretty miraculously and was ready for the start of the ’19-20 season, albeit without having had a proper offseason of recruiting and preparation. The team struggled again as Anderson continued to recover from the stroke, finishing his second campaign with a record of 10-20.

Shortly after that season, another shockwave hit: COVID-19. Fisk’s entire ’20-21 season was canceled.

So here we are in August, 2021, and Mr. Chibbs is healthy and ready to rock. “I’m [a patient] at Vanderbilt Medical. They’re taking care of me. I have no limitations physically, but my memory isn’t so good,” he says.

One of Fisk’s returning players is Devyn Payne, a junior PG out of Memphis. He raves about playing for Anderson. “Playing for Kenny is a lifetime dream,” Payne says on the phone from campus during the first week of the school year. “He’s a known NBA legend. He was that dude. That dog. He still has it, too. He’ll shoot the ball, toss it around his back. He’s still got the sauce.”

Glover says that Anderson’s presence at the school has meant better recruiting pipelines, more attention from alumni and more media interest. “The alumni from the ’80s and ’90s really know about his career. The players don’t know too much, but their parents do! So that helps,” Glover says. “I think this year, he really made his mark with recruiting. He’s been working some camps. We’re getting a level of player we haven’t had before.”

Fisk has had erratic conference affiliations over the years (and been an independent at times) but this year the Bulldogs are rejoining the Gulf Coast Athletic Conference, which the school had previously belonged to a decade ago (other members include New Orleans-based universities Dillard and Xavier. Word to Scoop Jackson). “It’s the only NAIA league that is all HBCUs, and we’re very proud to be a part of it,” says Fisk Sports Information Director Scott Wallace.

NAIA schools do not offer traditional athletic scholarships, but can give academic scholarships to players who are also great students. Given Fisk’s academic standards, Anderson’s recruits need to clear a particularly high bar. “It’s kinda hard being so big on academics,” concedes Payne, who majors in Business Administration. “The requirements to get in are hard. Making the honor roll here means a lot. Graduating from Fisk means a lot. People know it’s tough over here. It’s good because Fisk is historic and known for academics, but it is hard for recruiting.”

“Basketball is secondary here,” Anderson confirms. “You gotta be real educated. I want to help kids get themselves a real good career.”

Adds Payne, “He is always on us about being in class, getting our schoolwork done. He talks about that a lot. He always preaches about hard work, academics and life. Then basketball. I love playing for him.”

This is absolute music to Vincent Smith’s ears. “Anytime you can help young men get better, you feel great about it. Each one, teach one. People gave a lot to Kenny and now he’s giving back,” he says.

Whatever impact Anderson is having on the young men who play for him is matched by what the experience is doing for him. Unsurprisingly, if you follow the rapid-tweeting legend, Kenny works the addictive platform into his explanation of how the job and his life are playing out.

“I’m going to be off Twitter from August 15-March 1,” says Chibbs, who had already broken his vow as of press time in the form of RTs, though he has avoided typing out any original tweets. “Everybody is going to miss me on there and it’s gonna be tough for me. But I’m gonna read novels. I’ve gotta gravitate to other things. All positive. My mother passed away and she wanted me to change my life. This job has changed me a great deal. That’s what my mother wanted.”

“Kenny’s mother would be running around and jumping up and down,” Smith co-signs with a chuckle. “She’d be so happy with what he’s doing right now.”

Ben Osborne is a former SLAM Ed. and is now Head of Content for Just Women’s Sports.

Photos via Tamara Reynolds and Getty Images.