Led by Guest Editor Carmelo Anthony, SLAM’s new magazine focuses on social justice and activism as seen through the lens of basketball. 100 percent of proceeds will be donated to charities supporting issues impacting the Black community. Grab your copy here.

—

As told to Isis Haywood and Kaela Crowell:

There were some really painful moments over my career, but somebody had to go through it.

I’m not saying I’m the only player that’s been through hard times, but I think the choices I made as a young player were crucial for those that came after me. Now is the time for the truth to be heard.

From the 1800s, slaves were often renamed when they stepped on the plantation. Names meant identity—by changing them, owners were re-scripting identities for hundreds of years.

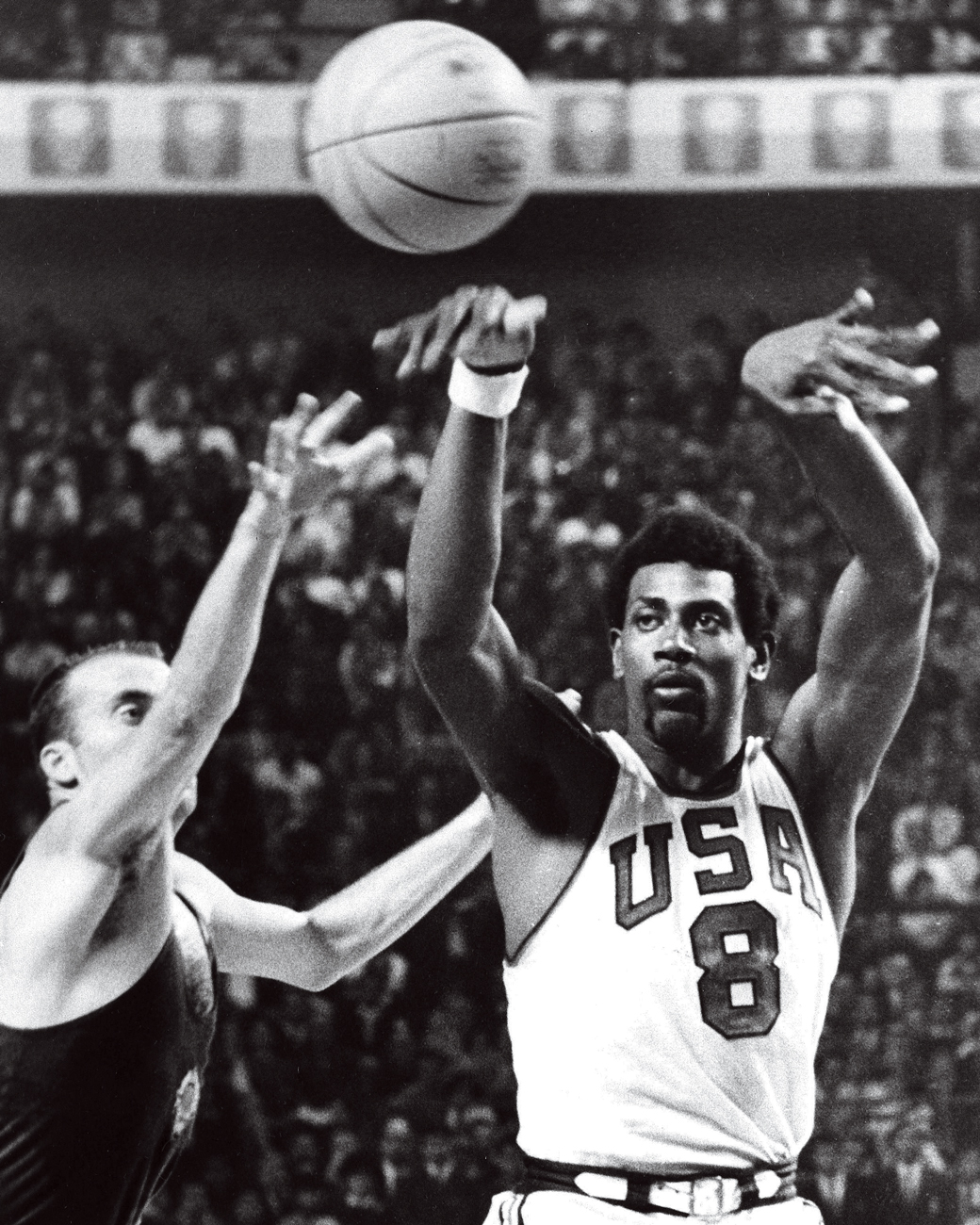

I grew up with the idea in my head that I was going to be the best cotton-picker in the state of Mississippi. That was my goal. Who am I now? Some know me from playing on the US Olympic basketball team. Some know me from my years in the NBA and the ABA. I’d venture a guess that most know me as the 21-year-old who, in his first NBA season, went through a battle in the Supreme Court. Haywood vs NBA overruled an old requirement that a player could only be drafted by an NBA team four years after his high school graduation.

I doubt, however, that many people know my story up to that point.

I am a Black man from the Deep South, born in the heavily sharecropped area of Mississippi. I lived in what was modern-day slavery. In the 1940s, my mother and father weren’t afforded the privilege of choosing a soulmate. To put it simply, they were paired to create a family of tall and strong negroes because cotton is heavy. My father passed away from a heart attack while my mother was carrying me. He was climbing a ladder, in the process of building an additional room for the family. There was little concern for the comfort of the 10 of us on the plantation—our sole purpose was to make the white people rich.

I was born in 1949 by the assistance of a mid-wife because hospitals did not accept Black people at the time. I was child No. 8 in the family line.

I learned how to pick cotton before I took my first steps. My first memory is riding on my mom’s cotton sack and her saying, “Pick the lower bowls of cotton, son, because I don’t want to bend down with my back.” My dad’s name was changed many times through the years. The name “Haywood” was for people who worked in carpentry, so my life was seemingly predetermined. I was to be a carpenter or a cotton-picker. At 13, I became the primary source of income for my family. I picked up to 200 pounds of cotton for $4 a day.

Around the age of 14, I began work as a caddy at the country club to get out of the cotton field. It was there that a joke rooted in racism and hate was designed to ruin my life. A few men welded a quarter onto a nail, so I bent to pick it up. I pulled hard to get it off and then was accused of trying to steal it. The man overseeing the club brutally punched me in the face and I fought back. I was thrown in the Belzoni jail and knew I was destined to be placed in Parchman Prison, where I would be forced to work on a farm for the rest of my life. My mother understood I had to flee from Mississippi. She said to me: “Whatever happens, you got to get out of here because you have something special to give to the world. You’re my baby and I gotta get you out of here. You’re different.” We gathered all of our money and I caught a bus up north.

I went to live with my brother Roy, a student at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. I had all of my belongings in a 10-pound paper bag—one pair of shoes, one pair of pants and one shirt. Most of what I knew up to that point was picking cotton. My brother heard of a basketball showcase in Michigan and decided to put me in an exhibition game. I had played throughout my childhood and was very tall. Because of those exhibitions, my talent was discovered.

I was further motivated to succeed for my family back home. Players would throw away their Converse shoes for adidas ones, and I’d dig up the old pairs and send them to Mississippi.

I dominated at the age of 15. I was schooling the other high school players easily. Will Robinson, a family friend and mentor of mine, decided to put me up against college-level players to see if I would still dominate. And I did. Then Robinson had me compete against the pros from the Detroit Pistons. And I beat them, too. While juggling my new life as an athlete, I battled with finding a new identity away from the cotton field. I struggled with my English. I was also forced to walk with books on my head to correct my posture—I was so used to looking down to show submissiveness to my white owners in Mississippi.

During my first high school season, I was an All-American. By my second year, I was one of the top players in the world. I went to the University of Tennessee, becoming one of the first Black players in the Southeastern Conference. From there, I moved on to Trinidad State Junior College, the same year as the 1968 Olympics.

Because I was at a junior college instead of a major university, I was able to try out and was eventually picked for the Olympic Games. They were held amid the civil rights movement, so brilliant Black athletes not only trained to compete but also strategized protests to stand against racism. I helped bring back the Gold medal for Team USA and Black people greeted me as soon as I stepped off the plane. I scored the most points of any Olympic basketball player until 2012, when Kevin Durant broke my record. One of the coaches in Mississippi decided to hold a parade for me, saying: “He’s one of us.” But what did that truly mean? I wasn’t afforded the privileges of white people, so I did not attend. Returning to Mississippi would’ve reminded me of the injustices I faced since birth.

Still, my success was being celebrated in Mississippi, and for the first time, the name Haywood meant something different. When my mother was on her deathbed, I asked her: “What was the worst thing I did?” She said not coming back for that parade, because our families had struggled for over 200 years to get our name respected. Through me, my mother had hoped to change the meaning of the Haywood name, to be more than a cotton-picker or sharecropper.

I returned from the Olympics with a plan to play at the University of Detroit and get my friend Will Robinson chosen as the first Black coach in the NCAA. I felt a responsibility to the Black community. I just wanted all of us Black people to succeed.

Once I officially signed, the organization drew back on their promise to make Will the coach. I felt betrayed and lost. I wanted to leave school, but I was out of options. I played one season and then had to make a decision. Transferring would mean I’d have to wait a year before playing again. I was invited to join the ABA, a professional league. In my first season (1969-70) for the Denver Rockets, I was named Rookie of the Year and won MVP, averaging 30 points and 19.5 rebounds. My contract was for 1.9 million and I was apparently the “highest-paid player in the basketball universe.” The deal consisted of around $400,000 paid out over four years, and I was told that the $1.5 million was supposed to accrue from a long-term annuity tying me to the organization. None of it was guaranteed. I asked for the contract to be adjusted, considering I signed it underage. I had trusted that it would be written with integrity after everything I did for the ABA. When I walked in with my lawyer, who happened to be Jewish, the owner said to us: “Get your nigger ass out of here and take that Jew-ass lawyer with you.” Word for word. I realized that these guys were like the same white owners I had from birth. It was like I was back in Mississippi.

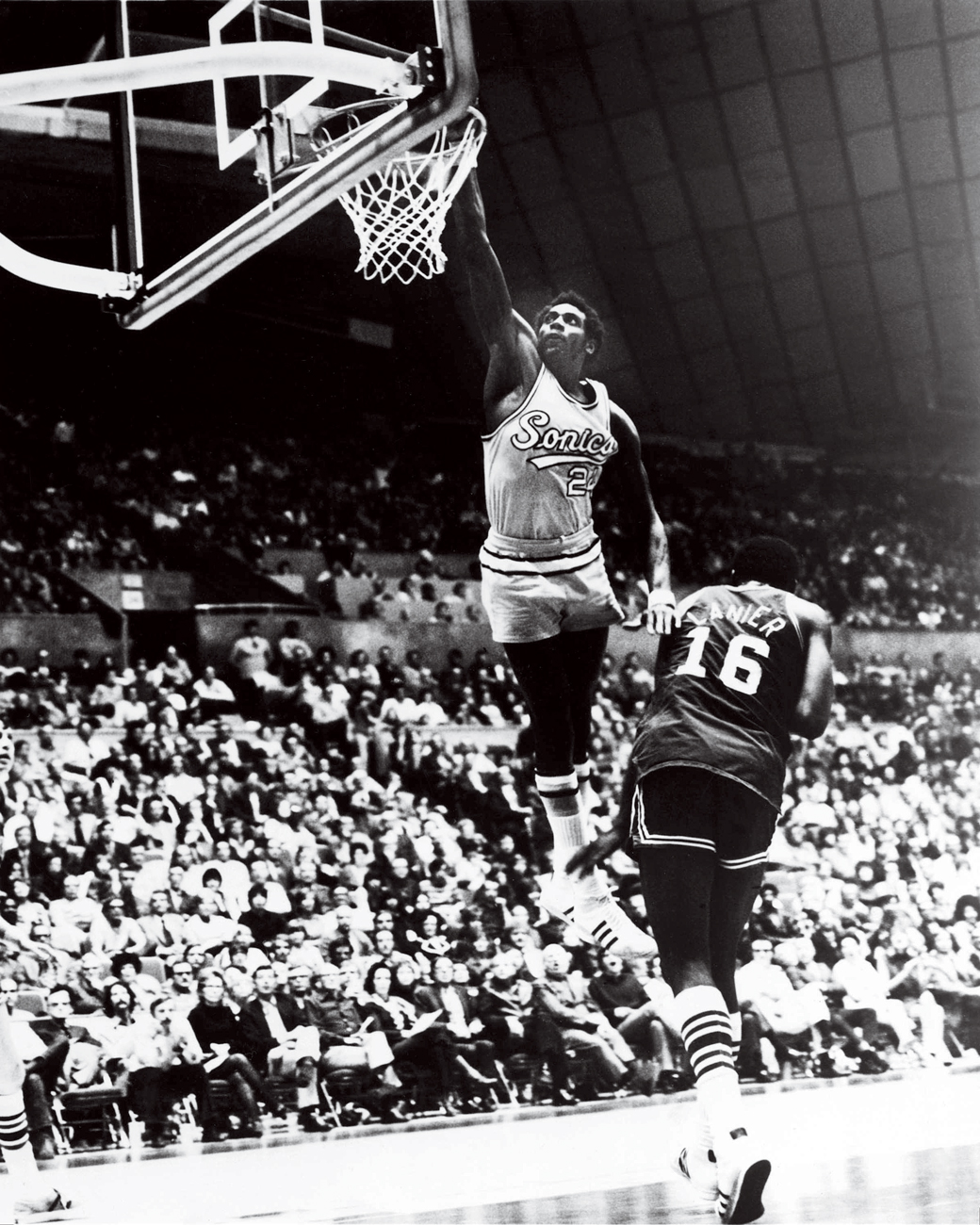

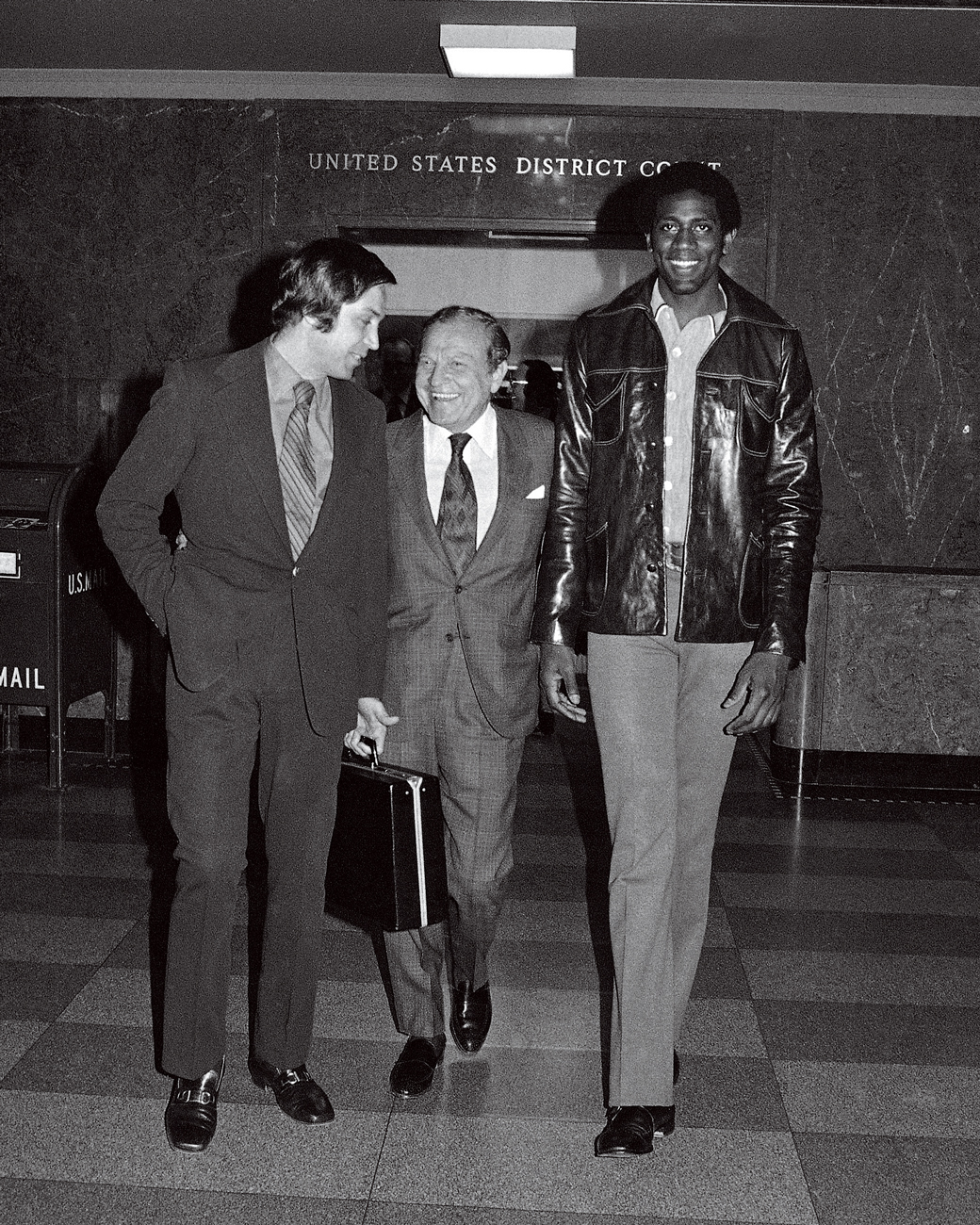

I couldn’t go back to a university, having already completed a year in the pros. And at the time, I wasn’t permitted to enter the NBA until I was four years removed from high school. I met the owner of the Seattle SuperSonics, Sam Schulman, who was willing to sign me and fight against the League on my behalf. We launched an anti-trust suit that would come to be known as Haywood vs NBA. In the meantime, I was playing games for Seattle in the face of adversity and hate. Imagine this: An announcer would come on the loudspeaker in front of thousands and say, “Ladies and gentlemen, we have an illegal player on the floor! No. 24, Spencer Haywood, must be exported out of the arena!” Sometimes they’d do just that—toss me from the building.

Fans would antagonize me with remarks like, “You’re destroying basketball as we know it!” In my mind, I was the perfect candidate for this movement because I had been through this my whole life, starting in the cotton field. I didn’t break. Despite the challenges, we took Haywood vs NBA all the way to the Supreme Court. They ruled 7-2 against the NBA’s old requirement that a player had to be four years out of high school to enter the League. It changed the game forever.

My motivation was considering all the future players. The NBA’s position shifted once they realized that if they had guys coming in early, they could expand the organization from 14 teams. It grew the worth of franchises. My sacrifices have made owners and players rich. I feel as though I carved out a space for Black athletes to be millionaires. I’m not looking for praise, but the part that hurts is that for years I would go up to a player and say to him, “Hey man, I’m Spencer Haywood, just wanted to introduce myself.” And they would turn their backs on me.

The NBA gained billions for my actions but said that I would never be recognized for the work that I did. I was to be an example of what could happen if you challenged them, so they excommunicated me. I was turned away from the Hall of Fame twice, despite all of my accomplishments.

I was finally inducted in 2015, but many players didn’t even stay to watch the screening of my video. They have never fully embraced me for what I’ve done. None of the players who went straight to the NBA out of high school—Kobe, LeBron, KG, T-Mac—would’ve been able to do so without the Spencer Haywood Rule. None of the players who left college early for the NBA—Bird, Magic, Jordan, Zion—would’ve been able to do so without the Spencer Haywood Rule. The truth is, most players come into the NBA under the Spencer Haywood Rule. And I believe it should bear that name, just like the Oscar Robertson Rule or the Larry Bird Rule.

I watched players I dominated on the court make it into the Hall of Fame before me, but because I was not passive about oppression, I did not get the same nod.

The struggle has been ongoing for 400 years. My story tells of the pain that many other African American men have faced. I didn’t have many options in my time, but you do. Protest, march, go into the spaces that celebrate you as Black athletes and people, whether it be attending an HBCU or refusing to play for ownership that doesn’t see the color of your skin. Be intentional about your decisions—taking a stand could be the move to change your career and generations of lives after you.

My name, my voice was silenced for years. What I really want is respect for what I did, from players and from our community. That would mean everything to me.

Black people’s purposes have been attempted to be pre-defined for us since the beginning of time. Giving us specific names like Haywood based on what we were supposed to do to help white people. Or even attempting to dismiss that name, discouraging courageousness and allowing for a continued cycle of systematic oppression. The time has come where Black people’s voices will be heard, and others will have no choice but to listen.

My name is Spencer Haywood. What’s yours?

—

100 percent of proceeds from SLAM’s new issue will be donated to charities supporting issues impacting the Black community. Grab your copy here.

The Spencer Haywood Rule, a book about the life of the Hall of Famer by Marc J. Spears and Gary Washburn, is available for preorder now. Grab your copy here.

Photos via Getty.