It was one of the most iconic plays in NBA history, although it only lasted a few seconds.

Michael Jordan, the greatest basketball player in the world—many say of all time—applied his suffocating defensive skills to rookie guard Allen Iverson, a feisty prodigy whose approach to the game couldn’t have been more different. That March night in 1997, the 6-0 Iverson came off a screen with the ball at the top of the key as the 6-6 Jordan guarded his man. Bulls Coach Phil Jackson hollered “Michael, get up on him Michael,” signaling for his superstar guard to switch off of his man and onto Iverson. AI spied Michael through his peripheral vision as he came near, and everyone in the arena stood up in eager anticipation of Jordan clamping down on Iverson with his swarming defense. AI hit Jordan with a feint of a crossover first, just to set him up. He didn’t intend to rehearse his move in front of MJ. He simply didn’t get it right. Despite his initial failure, Jordan bit the bait and fell for Iverson’s faux crossover. “Oh shit,” Iverson said to himself, “I didn’t even do it for real, and he went for it.” It boosted his confidence and fueled his drive to topple the master with his signature move. Iverson then cocked it back and hit him with it. Boom! It was lighting quick and left Jordan’s legs twisted. He thought Iverson was heading one way, but he actually went in the opposite direction toward the basket and drained a jump shot. The crowd erupted in applause.

That Iverson bested Jordan and “broke his ankles” underscores an athletic truism: basketball is a game where youngsters grow up to battle their heroes. “I remember the first time I played against him—he didn’t even look human,” Iverson tells me today. “He looked to me on that court the same way he looked when I was a 10-year-old kid looking at him on television. This is the man I wanted to be like.”

Almost 15 years later, the move inspired hip-hop superstar Drake to drop a couplet that summarized the often ruthless transition between styles and generations: “And that’s around the time that your idols become your rivals/You make friends with Mike but gotta AI him for your survival.”

Iverson lived up to his nickname “The Answer” as he solved the riddle of Jordan’s hardwood omniscience, at least for a play, badgering the basketball deity with a devilish move that left him flummoxed in his sneakers. Iverson had practiced the move at Georgetown in the mid-’90s as a collegiate star before refining it in the League. But at this game, the last of the season, the Chosen One, and through the miracle of the media, the nation at large, too, got a taste of Iverson’s wicked crossover—a term that conjures Iverson’s complicated, even tortured, odyssey to mainstream success as he held fast to the tenets of his hardscrabble youth. The crossover, a move that Iverson didn’t patent but brilliantly reinvented, is far more difficult than it looks. One must master the physics of momentum, the calculus of velocity, the geometry of space and the aesthetics of illusion. The crossover is equal parts magic and science.

Iverson didn’t initially think much of the play. The crowd always went crazy whenever he crossed over any player. It wasn’t until he got home and flicked on the tube that he discovered it was all over the local news and on frantic repeat on national sports television. That’s when it hit him that this was something truly special. In the 24-hour sports media machine, events that happen locally take on national significance when they’re isolated and examined and heavily repeated so that their meaning is either exaggerated or rescued from potential erasure. ESPN’s SportsCenter is a major outlet for such events; they’re the unofficial curators of outsize sports moments. Their iconic segment “Top 10 plays” catalogues great sports achievements across the athletic spectrum. SportsCenter seized on Iverson’s crossover move on Michael Jordan and looped it with archival intensity. SportsCenter’s coverage gave the move gravitas and made it a legendary gesture because it happened against the game’s greatest player.

But if the information-starved, details-hungry 24-hour sports news cycle benefitted Iverson, it also turned on him. He was everything Jordan wasn’t—and everything the NBA was ill-prepared to handle. Jordan and Iverson hailed from two different galaxies. Jordan was a clean-shaven, suit-and-tie wearing, All-American face of the League. If not the logo, as some believe he should have been, Jordan was at least the game’s gold standard.

Iverson, on the other hand, was a tattoo-bearing, cornrow-sporting, Starter-wearing wunderkind who shook the nervous guardians of the League’s image. Jordan’s courtly elegance reflected ’80s “quiet storm” rhythm and blues and smooth jazz. Iverson was unvarnished ’90s hip-hop, and his rat-a-tat pace and staccato rhythm of play mimicked the music, and urban culture, from which they both sprang. Jordan was Kenny G; Iverson was The Notorious B.I.G. Iverson may not have won any titles, but he championed street style and hood smarts while forging a durable link with millions who vicariously lived through him and proclaimed him a ghetto god. Their showdown was epic, not because Jordan and Iverson met in a game where a new victor would be crowned, but because two competing universes of black identity came crashing down on an insignificant encounter and lent it transcendent meaning.

To be sure, Iverson is remembered for his dazzling acrobatics and for his fearless drives to the basket on domineering forces in the paint like Shaq. But those aren’t the only images that remain. Burnt into the nation’s memory of Iverson are the braids, the body ink, the baggy hip-hop gear, the flashy jewelry and the bad boy reputation, one that started with a high school brawl in a bowling alley that unjustly landed him behind bars and almost ended his storied career before it got started. The man who gave Iverson a second chance played a huge role in his life and career and proved the virtue of black belief in redemption.

It must be stated that a lot of what we think we know about Iverson simply isn’t true, is easily misunderstood, or is sometimes deliberately misinterpreted, either because the media was lazy, or he was occasionally his own worst enemy. More often than not, Iverson was viewed through the distorted lens of a culture that had little tolerance for young black men who bolted suddenly from abject poverty to astonishing wealth and fame.

Iverson admits that the fast come-up that he and so many other ballers and rappers experience often leads to a head rush that is at once intoxicating and disorienting. “Just being young, 21, 22 years old, never having nothing, then all of a sudden you’ve got millions of dollars, you’re going to do what you want to do,” he remembers ruefully. “That’s the first thing you think about: getting everything that you always wanted, all the things that you dreamed that you were going to have in your life. And I was no different from anybody else. And then they started destroying me over it.”

“They” also destroyed Iverson for hanging with his boys from the hood, which to him was a just reward for loyal friends who stuck by his side when he was poor and anonymous. Now that he was rich and famous it would be heartless to abandon them and deny his friends the payoff for their faith in him. “You see me with five or six guys from my neighborhood? That’s what you’re supposed to do when you make it. It didn’t sit well with people, and they started killing me over it.”

Iverson became the poster boy for all that was wrong in the NBA, when in truth he reflected his generation and their way of negotiating the world. Iverson’s attire, for instance, wasn’t meant to flash a brazen indifference to the respectability politics of the NBA—though it certainly did—as much as unapologetically embrace the way people his age dressed in the hood. He may have loved the way Earvin Johnson threaded the needle with a pass, but he passed on his idols’ needles and threads. “As much as I wanted to be like Michael Jordan, that wasn’t how I dressed,” Iverson says. “I wanted to shoot like Bird. I wanted to pass like Magic. I wanted to be fast like Isiah. I wanted to jump like Mike, rebound like Rodman. I tried to add all of that edge to my game. But who I am as a person, and my overall style, and the way I dress, and the people that I hang around, it’s nothing like that. That was a part of their life that I didn’t want to emulate. Because I was satisfied with my own.”

Iverson’s self satisfaction got under the skin of some of his elders and the NBA office, but spilled rapidly onto his own flesh with purposeful expression. “And then I got a tattoo…and then I got addicted to them,” Iverson says. “I got another one. Then I got another one.”

Iverson was especially upset when Hoop, an official NBA publication, decided to airbrush his jewelry and tattoos from its January 2000 cover photo of the Philadelphia 76ers superstar. “That’s what hurt me the most. I don’t just have tattoos like a rainbow on my body, [or] designs…[but I have] my mother, my grandmother, my kids, my wife. Those [tattoos] mean something to me.” Iverson’s body was the gateway—more precisely the sacrifice—for the acceptance of tattoos on ball players’ bodies. It is rare today to see basketball players without an inked message on their skin. Iverson blazed the path for them.

Iverson’s hairstyle, too, meant something, even if he kept his locks plaited for far more practical reasons—not because he was a hooligan. “I didn’t get cornrows because of no thug shit,” Iverson protests. “My whole thing with the cornrows was just I would go on the road, and barbers in different cities would mess my hair up. So I figured, shit, if I get my hair cornrowed, I wouldn’t have to worry about that. It’s a long season. Then that turned out [supposedly] to be some thug thing.”

What he couldn’t so easily change, perhaps to this day, is the perception that he hated practice—an impression left by the same media that had lifted him to glory because of his crossover on Jordan. Most people don’t know the story behind the “practice” riff that gives it a far more sensible context, even if it is still admittedly funny after all these years.

Iverson’s comments came after an ’01-02 campaign where he had to contend with the constant drumbeat of trade rumors. The most public round of speculation had been set off with the incendiary words of his head coach, Larry Brown. Iverson adored Larry Brown as a man and admired him as a coach, but he felt that Brown made some ill-advised comments about not being able to coach Allen and about Iverson missing a single practice. That single miss somehow got translated into Iverson ditching practice and dodging his responsibilities as a team leader.

Iverson was a young player when trade rumors flared. The Sixers brass finally sat down with Iverson and assured him that he’d remain with the team for the foreseeable future. Iverson knew he hadn’t been perfect and wanted to right the ship and calm the tumultuous waters by setting a good example for his teammates. Iverson and the Sixers called a press conference to give the world the scoop. But the media was obsessed with all the rumors that led to the speculation that he’d be traded, and dogged by the misperception that AI wasn’t interested in discipline and practice—and not much interested in the news that he wouldn’t get shipped to another team.

“Could you be clear about your practicing habits since we can’t see you practice?” a reporter quizzed. “If Coach tells you that I missed practice, then that’s that,” Iverson stated as matter-of-factly as he could. “I may have missed one practice this year. But if somebody says he missed one practice of all the practices this year, then that’s enough to get a whole lot started.”

“So you and Coach Brown got caught up on Saturday about practice?” yet another follow-up question rang out.

And thus Iverson’s rant on practice began. The sheer repetition of the word itself took on a mantra-like quality. It did appear for a moment that Allen was caught in a trance where he exploited every nuance of the word’s meaning by inflecting his voice and stressing different pronunciations as much for poetic meter as for rhetorical emphasis.

“If I can’t practice, I can’t practice,” he insisted. “It is as simple as that. It ain’t about that at all. It’s easy to sum it up if you’re just talking about practice. We’re sitting here, and I’m supposed to be the franchise player, and we’re talking about practice.”

Iverson felt the surge of repetition coming on and there was nothing he could do about it. He was swept into a stream of consciousness and his mouth was the voice of his bruised soul.

“I mean listen, we’re sitting here talking about practice. Not a game. Not a game. Not a game. But we’re talking about practice. Not the game that I go out there and die for and play every game like it’s my last. But we’re talking about practice man. How silly is that?”

Iverson was clearly exasperated, and once it got started, he seemed incapable of quenching the rush of words that centered on the word the media kept tossing at him.

“Now I know that I’m supposed to lead by example…I know it’s important, I honestly do. But we’re talking about practice. We’re talking about practice man.”

The room burst out in laughter as Iverson repeatedly rolled practice from his tongue with an impish grin on his face, taking refuge in humor to combat the absurdity of the situation.

“We’re talking about practice. We’re talking about practice. We’re not talking about the game. We’re talking about practice. When you come to the arena, and you see me play…You’ve seen me play right? You’ve seen me give everything I’ve got, but we’re talking about practice right now.”

The clip of him talking about practice soon went viral, a casualty of the culture’s athletic obsession, the same one that helped to launch his reputation when he had his encounter with Jordan a few years earlier. The practice incident is really a metaphor for how Iverson was beset by problems of distorted perception, and those of his own making, although, on balance, as King Lear declared, he was more sinned against than sinning.

One of the most egregious sins against him happened on February 14, 1993, when Iverson and several of his Hampton, VA, high school teammates were in a bowling alley blowing off steam and having fun like any red-blooded American youth. A couple of black guys got into an argument with a couple of white guys, and things got ugly as racial slurs and punches were thrown in rapid succession. Iverson was accused of hitting a white woman in the head with a chair. Fortunately someone had videotaped the incident, clearly showing he wasn’t involved in the mayhem. But it wouldn’t do him much good because the legal powers that be didn’t allow the tape in court to prove his innocence.

The prosecutors were so determined to nab Iverson that they waited more than six months to try him as an adult, even though the brawl took place when he was a minor. Iverson was later convicted of the felony charge of “maiming by mob,” a rarely used Virginia statute to combat lynching after the Civil War that was resurrected just for him. They threw the book at Iverson and gave him 15 years in prison, with 10 years suspended, to make sure that he wouldn’t escape responsibility for the crime. Four months into his sentence, Virginia’s first black governor, L. Douglas Wilder, granted him clemency. It wasn’t long before Iverson met Georgetown Coach John Thompson, a figure who would change the course of his life—a giant of a man who had a heart as big as Mother Teresa’s and a mouth as colorful as Richard Pryor’s.

Iverson’s mother Ann went to coach Thompson and persuaded him to give Allen a spot on his roster once he was free and finished with his high school requirements. Iverson established himself at Georgetown as a force to be reckoned with on the hardwood while Thompson, a former Celtics backup center for Bill Russell, became a father figure who protected Iverson and kept drama from coming his way. In a sense they reversed roles: Iverson was the center of his attention and Thompson guarded Allen from harm.

That was no small feat, especially since he’d just spent four months of his life in prison with the threat of losing his career in sports forever. When Iverson was in prison, he received several death threats each day. Once a scarecrow with his jersey was hung on a tree outside the prison with the strong suggestion of lynching. It was a rude awakening for Allen to go from hundreds of recruiting letters to hundreds of daily death threats. The threats and hostility continued at Georgetown, most of which Thompson kept from Iverson. When reporters sidled up to him to ask about his time in prison, and not his performance on court, Coach Thompson shut them down.

Coach Thompson’s willingness to battle for Allen made the latter even more determined to do battle for Thompson and the team, and it’s hard to overstate Big John’s impact on Iverson’s career. He provided perhaps the greatest moment in Iverson’s life as a basketball player. It was an incident that profoundly shaped his self-confidence for the rest of his career. It was like a scene from a Hollywood movie.

In Iverson’s second and final year in the program, the Hoyas were on the road in the middle of a grueling effort to make it back to the top of the Big East. The coaches had informally assembled in a bathroom, thinking they were the only ones there. What they didn’t know is that Jerry Nichols, one of Iverson’s teammates, was posted on the toilet in a stall. As soon as the coaches disbanded, Nichols rushed to tell Allen of the conversation the coaches had in their makeshift training room.

“Man, I was in the bathroom and you wouldn’t believe what happened,” Nichols breathlessly blurted out to Iverson.

“What man?” Iverson impatiently implored.

“The coaches were in there talking about you.”

Iverson thought that it was surely negative. He steeled himself for the criticism, making up his mind to improve his play based on the insight his eavesdropping comrade could offer. But his preemptive worry proved unnecessary.

“Coach Thompson said, ‘That little motherfucker is a baaad motherfucker.’”

There have been far more eloquent assessments of Iverson’s play, his impact on the game, his remarkable skills, and his killer instinct. But in the end, Thompson’s words are as fine and fitting a summary of Iverson’s basketball career as might ever be uttered.

—

Michael Eric Dyson is a University Professor of Sociology at Georgetown University and an award-winning writer whose work has been featured in the Op-Ed Section of the The New York Times, The New Republic and in the best-seller section of your local bookstore—where you’ll find his most recent work, The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America. Follow him on Twitter @MichaelEDyson.

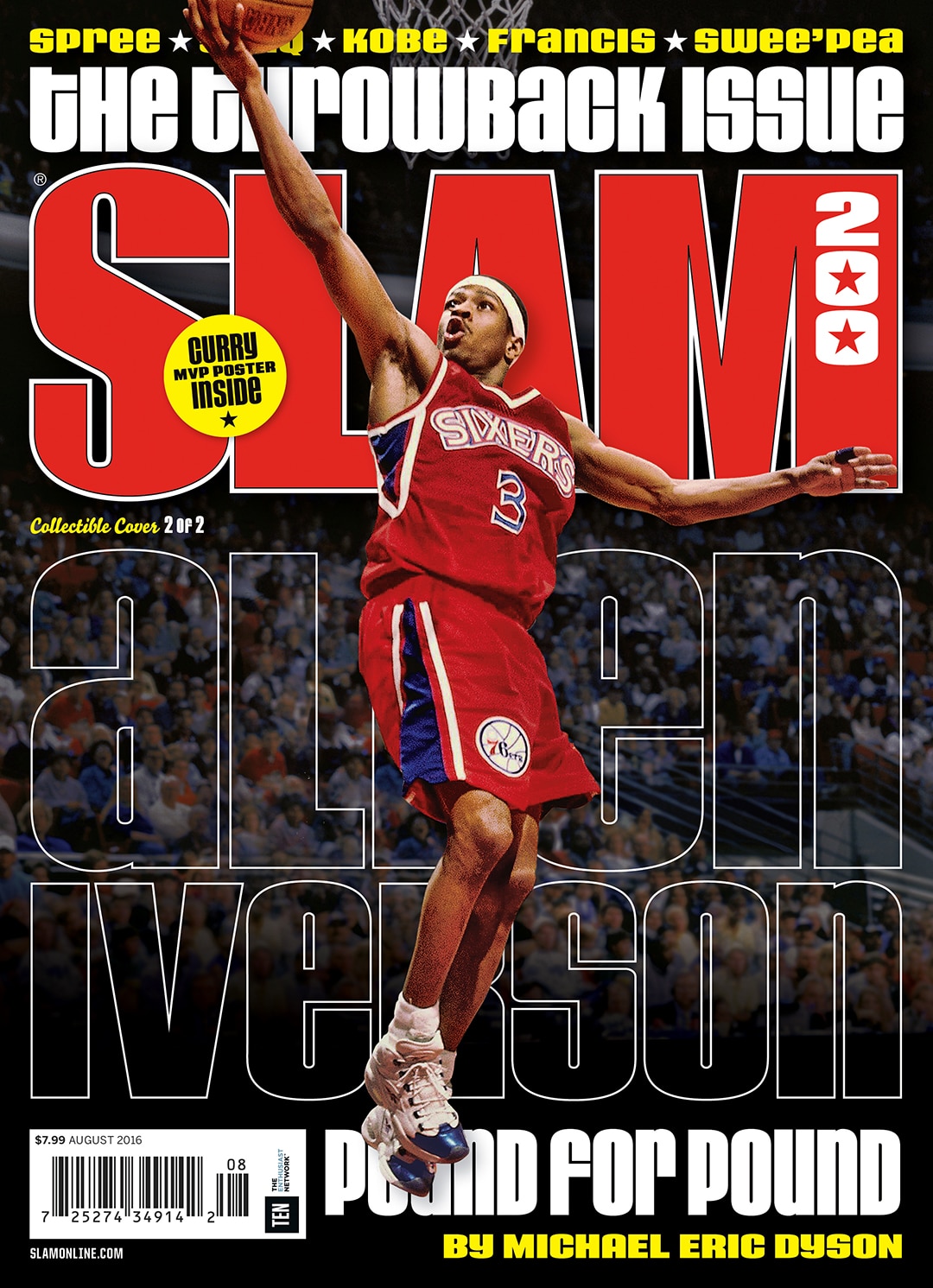

Photos via Getty Images