It’s Labor Day 2017 and the summer is wrapping up following months of political strife, protests and tragedy. The turmoil reached a boiling point during the weekend of August 12 when white supremacists and Nazis descended upon the city of Charlottesville, VA, for a “Unite the Right” rally that resulted in the death of 32-year-old Heather Heyer, who was killed when James Alex Fields Jr intentionally drove his car into a group of protestors.

As the events unfolded, NBA players took to Twitter to echo the feelings of shock, fear and disgust that the majority of the public was experiencing. Donald Trump fueled the fire by refusing to immediately condemn the supremacists, claiming at a press conference that there was violence on “both sides.”

Days later, LeBron James spoke at his foundation’s annual family reunion and used his platform to call Trump the “so-called president of the United States.” James then made a plea for those in attendance to take a look in the mirror and ask, “What can we do better to help change?”

NBA players—and professional athletes in general—have a long history of being involved in social, political and race issues. Over the past few years, more and more marquee players have been using their status to voice their views and help promote change. LeBron, along with friends and fellow superstars Carmelo Anthony, Chris Paul and Dwyane Wade, stood on stage at the 2016 ESPYs—just one week after the deaths of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling at the hands of the police—and called on celebrity athletes to “Speak up. Use our influence. And renounce all violence.”

The acts of those four superstars have had a trickle-down effect, with more and more NBA players getting involved in community efforts, speaking out against racist violence and actively participating in protests, following in the footsteps of activists like Bill Russell, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Isiah Thomas.

“We all have feelings and we just want to talk about [issues] the right way,” says Karl-Anthony Towns, who penned a piece for The Players’ Tribune following the violence in Charlottesville. “I just try to be positive and do it the right way. I don’t want to bash anyone. I want to spread love and respect to everyone. I want to remind people of our situations and do that with love and respect.”

In the NFL, America’s most popular sports league, quarterback Colin Kaepernick remains unsigned as of press time as more and more no-name quarterbacks take the field. Kaepernick has become the center of attention following his decision to protest the National Anthem by sitting during the playing of the song before a 2016 preseason game. Later on, he started taking a knee before games as the Anthem played. “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color,” Kaepernick told NFL media in late August of ’16. “To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

Kaepernick is widely believed to have been blackballed from the NFL because of his protest. Throughout the preseason, players across the NFL showed their support for the quarterback by kneeling for the anthem and saying that Kap should be on a roster if team owners and general managers are serious about winning games. It’s clear that keeping Kaepernick off the field is not going to silence his message or simply make him go away.

With the NBA season looming and players becoming increasingly politically active, it begs the question as to whether we’ll see more activism on the hardwood in the same vein as Kaepernick’s.

“I think there are some players that have enough courage to follow [Kaepernick’s] lead or help him on his journey,” Nuggets forward Wilson Chandler says. “I think if you were doing something to symbolize Kaepernick and what he’s done and what he’s trying to accomplish, a player would have to take a knee or something in that regard during the National Anthem. To be honest, I don’t think any of the players are going to do it. But if it were to happen, it would probably be something similar to that.”

But before we continue to look forward, it’s important to look at how the NBA has handled cases of activism and protest in the recent past.

Before the 1991 Finals against the Lakers, Craig Hodges, a three-point specialist for the Bulls, asked Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson not to take the floor for Game 1 as a way to protest the beating of Rodney King by four white LAPD officers. When the Bulls visited the White House in ’92 to celebrate their second-straight NBA title, Hodges wore a dashiki and handed President George H.W. Bush a letter that urged him to address the problems of poor and minority communities.

The Bulls would later release him and he never played in another NBA game.

‘’I thought we improved ourselves [at Craig’s position],’’ Phil Jackson told The New York Times in 1996. ‘’I had the highest regard for Craig, though. He was a great team player, never caused any problems and I respected his views. I’m a spiritual man, and so is he. But I also found it strange that not a single team called to inquire about him. Usually, I get at least one call about a player we’ve decided not to sign. And yes, he couldn’t play much defense, but a lot of guys in the league can’t, but not many can shoot from his range, either.’’

In 1996, Hodges filed a $40 million lawsuit against the NBA claiming that “the owners and operators of the 29 NBA member franchises have participated as co-conspirators” in “blackballing” him from the League “because of his outspoken political nature as an African-American man.” The case was later dismissed. Hodges bounced around internationally throughout the rest of the ’90s, but did find his way back to the NBA as an assistant with Jackson’s Lakers from 2005-11.

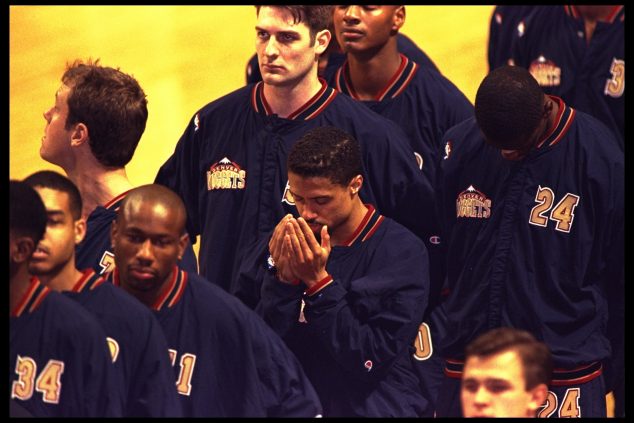

Also in 1996, Denver Nuggets point guard Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf was suspended by the NBA for refusing to stand during the playing of the National Anthem. Abdul-Rauf, a practicing Muslim, had been skipping out on the ceremony throughout the season, opting to stay in the locker room or stretch on the sideline. When asked by a reporter about his actions during the playing of the Anthem, the point guard said that the American flag was a symbol of “oppression, of tyranny.” Abdul-Rauf and the NBA came to a compromise: Mahmoud would stand for the Anthem, but would pray silently to himself with his hands cupped in front of his face.

Unlike Hodges, Abdul-Rauf was a starter—a damn good one at that. He averaged 19.2 points and 6.8 assists for Denver that season. The reaction to his protest divided NBA fans, and the controversy soon spilled out to the public sphere. Abdul-Rauf was met with death threats and had the letters “KKK” spray-painted close to the construction of his home in Gulfport, MS. He never moved into the home and in 2001, the vacant house was burned to the ground.

Abdul-Rauf, who was in his sixth season at the time, was traded to Sacramento and was out of the League by 1998. He returned for a brief stint in Vancouver in 2001, but his career was never the same after what happened in Denver.

“It’s a process of just trying to weed you out,” he told The Undefeated last year. “They begin to try to put you in vulnerable positions. They play with your minutes, trying to mess up your rhythm. Then they sit you more. Then what it looks like is, well, the guy just doesn’t have it anymore, so we trade him.

“It’s kind of like a setup. You know, trying to set you up to fail and so when they get rid of you, they can blame it on that as opposed to, it was really because he took these positions. They don’t want these type of examples to spread, so they’ve got to make an example of individuals like this.”

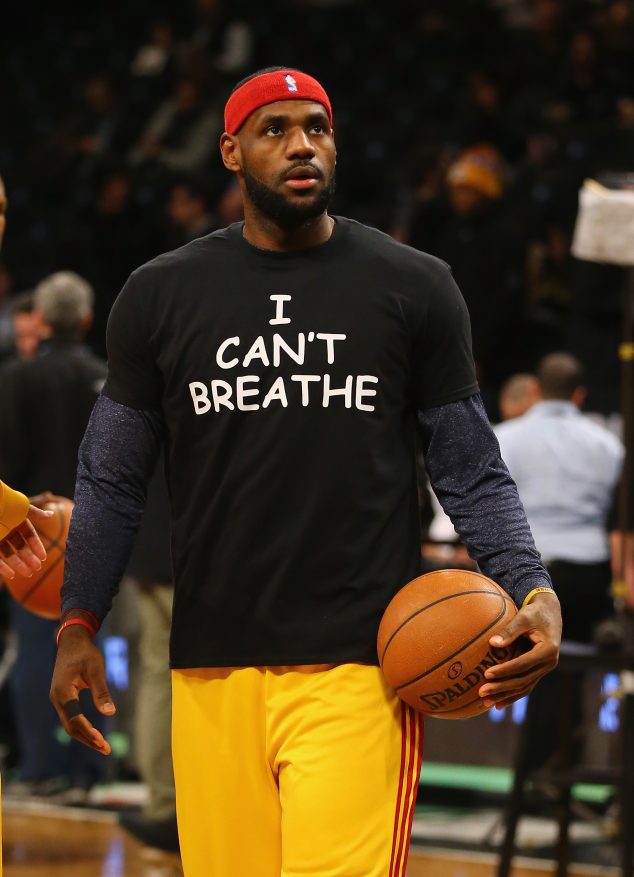

In 2014, players including LeBron, Derrick Rose, Kevin Garnett, Kyrie Irving, Deron Williams, Jarrett Jack and Alan Anderson wore “I Can’t Breathe” shirts during warmups after a grand jury decided that the officer who choked Staten Island, NY, resident Eric Garner to death would not be indicted. None of the players were fined for violating the League’s apparel rules.

Also in 2014, the Los Angeles Clippers staged a silent protest before Game 4 of the first round of the playoffs. The team was showing solidarity after audio of former Clippers owner Donald Sterling making racist comments was leaked to TMZ. The comments sparked outrage throughout the NBA, with LeBron saying at the time that “there is no room for Donald Sterling in our League.”

Sterling was subsequently banned for life by commissioner Adam Silver.

Based on recent history, the NBA has become more progressive and understanding of protest, and Silver and National Basketball Players Association Executive Director Michele Roberts recently sent a letter to the players saying that the “Players Association and the League are always available to help you figure out the most meaningful way to make the difference” when it comes to social issues. But it is impossible to totally look past the treatment of Hodges and Abdul-Rauf. There has been an increase in big-time players using their platform to raise awareness, but there has not been an NBA protest as divisive as Kaepernick’s kneeling during the National Anthem.

“[What happened to Abdul-Rauf] wasn’t that long ago,” Chandler says. “I would like to put my faith in the NBA and owners, it’s a wonderful organization and seeing how they handled the Donald Sterling situation, hopefully if a protest happened now, they wouldn’t blackball a player for exercising his constitutional rights.”

While we would like to believe that the NBA would act much differently than the NFL, we won’t really know until a marquee player takes a dramatic on-court stand.

Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban told The Washington Post, in regards to Kaepernick, that he’s “glad the NBA doesn’t have a politician litmus test for our players. I’d like to think we encourage our players to exercise their constitutional rights.”

With more and more people seemingly in tune with what’s going on in DC thanks to social media and 24/7 news coverage, it seems as if you can’t go anywhere these days without stepping into a conversation about politics. Will that carry into NBA arenas this season?

“I don’t think it will have much of an impact,” Cuban told SLAM via e-mail. “Most people follow political commentary as much as they follow cricket scores. For those of us who pay close attention, it seems like a big deal. For everyone else who goes to or watches games for the love of the team and game, it’s not something they pay attention to.”

NBA players have a chance, now more than ever, to use their platform to raise awareness about issues that hit close to home. As events become politicized and cause friction amongst the general public, we may soon find out if players are given an opportunity to speak up and spread a message of hope—or if they’re subtly discouraged from doing so.

–

Peter Walsh is a Senior Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @peter_m_walsh.

Photos via Getty Images