Ademola Okulaja was born in Nigeria, but moved to Germany with his family as a toddler. He earned a basketball scholarship to the University of North Carolina, where he started alongside Antawn Jamison and Vince Carter on Tar Heel teams led by legendary coach Dean Smith. Nicknamed “The Warrior” at Carolina, Okulaja played 13 years for the German national team and is a cancer survivor. These days, he works as a sports agent in Berlin.

A few years ago at a tournament in Hagen, Germany, Okulaja was finally introduced to a young player he’d be keeping an eye on for a while: a 17-year-old named Dennis Schröder.

“Dennis does not play like a typical German, and that’s what stood out. He was a 1-on-1 guy who could beat his man,” recalls Okulaja. “Give him the ball, space out and let him beat his man, either to finish or for the assist. He’s an incredible passer who sees the complete court. But he was criticized for passing too much. People said he was too flamboyant, that he’s trying to do Magic Johnson passes between the legs to 10 people. But it was just his style.

“He had a swag to him, but most people looked at that as a negative. I saw that as a positive. In basketball, you have to have self-confidence, but most guys saw it as arrogance. I liked it. I liked his swagger.”

The pair stayed in regular contact, and Okulaja made several trips to Schröder’s hometown of Braunschweig before eventually signing him as a client.

Fast forward to the present and Schröder, now 22, is sitting in the visitors’ locker room at the Verizon Center in DC. He’s getting set for a late-March matchup with the Wizards, with the pair of all-gold Air Max 1s he wore to the arena tucked underneath his chair and teammate Tim Hardaway Jr. blasting something vicious through his headphones at the locker to his right. On this night, Schröder will come off the bench to lead the Hawks to a 122-101 blowout win over Washington, his 23 points and 8 assists both team-highs in just 20 minutes of action. His irritating defense helps hold All-Star PG John Wall to just 2 second-half points. Late in the fourth quarter, an overserved Wizards fan in the lower bowl attempts to get his attention, bellowing, “17, you suck!”

Schröder’s back is turned to the fan, but it’s hard to imagine him not smiling if he heard it, since he’s familiar with the experience of killing the competition before they can even put a face to his name on the roster.

“Him being black in Germany and being a point guard, people look at him different,” explains Okulaja. “Schröder is a very typical German name. If you hear his name and you don’t know anything about basketball and then all of a sudden Dennis walks through the door, people are like, ‘Hold up. I thought Schröder’—they’re expecting a little whiteboy, just from the name.”

Schröder laughs about it now, remembering the confusion on opponents’ faces as he carved up defenses as a kid. But he admits that navigating the hoops culture back home was no joke.

“I didn’t have it easy. All the German people, like, white people, they didn’t say my name. They just came every time with, like, ‘He’s black,’” says Schröder. “It was terrible for me, but I knew, like OK, I just got to work.”

The son of a Gambian mother and German father, Schröder’s first passion was skateboarding, not basketball. The middle child of five, he didn’t play organized hoops until the head coach of the local club team’s youth program, Liviu Calin, recruited him straight off the skatepark as an adolescent. Schröder was fast, he was fearless and he took to the game with ease. But he says he didn’t really take basketball seriously until his father died suddenly of a heart attack.

“When my dad passed when I was 16, it became my goal to go to the NBA,” Schröder says. “Before that, I never could have imagined that I’d play in the NBA. But after 16 I knew, that was my goal. I need to make it, I promised him that.”

With a more disciplined approach, Schröder improved rapidly. He’d train all day, then stay up until 2 or 3 a.m. to watch live NBA games, paying special attention to his favorite players, Rajon Rondo and Chris Paul. By age 17, he was playing for both Braunschweig’s youth team and its pro team, simultaneously. He was a burgeoning star, but it was chaotic. Often, he’d miss practice with pro team when he thought he was supposed to be running with the youth team, or vice versa, and get unfairly blamed for the organization’s shortcomings in communication. Still, in a pro system where young players rarely get much playing time, Schröder showed scouts enough to get invited to the 2013 Nike Hoop Summit in Portland. He knew playing in the Hoop Summit was his only shot at getting the NBA to notice him for real, even if disappearing mid-season meant pissing off his club team.

The risk paid off. Dennis showed out, and two months later the Hawks made him the 17th pick in the 2013 NBA Draft. (“For Dennis, everything went from 0 to 100 after the Hoop Summit,” says Okulaja.)

Schröder showed up in Atlanta a fish out of water. To ease the transition, his sister and niece, and later his older brother, came over from Germany to live with him. After practice, his sister would cook for him, or they’d go to the Cheesecake Factory or Benihana or Potbelly. Hawks fans were intrigued by the foreign import with the blonde patch in his hair (a fashion compromise between Dennis and his mother, who suggested he go full blonde) who’d shown flashes in Summer League, but he barely played during his rookie season, and even spent a couple weeks in the D-League.

Rather than sulk, Schröder put in more work. When the team plane landed on the road, he’d ask an assistant coach to come with him to the gym, to work out before he’d even dropped off his bags at the hotel. After home games, he’d make one of his boys (members of #SchrodersSwagTeam aka the #FlexGang—the hashtags he says he started on Instagram just as a way to have easy access to all their pics from summer trips to Berlin or wherever else) rebound for him late into the night, often with an early morning practice only hours away. Those close to Schröder characterize his work ethic as relentless. Almost ruthless.

Schröder is so obsessed with honing his craft in fact that even when he’s lobbed a lighthearted question about his musical taste, he begins and ends his answer with, “I just try to focus on basketball.” (For the record, he listens to a lot of Migos and, on off days, he will occasionally kick it with young artists from ATL who have become friends, like Solo Lucci and K Camp.)

In his sophomore season, Schröder worked his way into a role as a key reserve, pushing starting point guard Jeff Teague for minutes as the Hawks reached the conference finals, and in 2015-16 he’s become as scary a weapon as there is coming off the bench in the East, averaging career-highs in points (11.1), assists (4.4) and minutes (20.3) per game. And his growth in the NBA coincides with an international career that’s even more impressive. Schröder made his German senior national team debut in 2014, and last summer he led the team in scoring at Eurobasket with 21 ppg (Dirk Nowitzki was second, at 13.8 ppg). He is, without question, the future of German basketball. Just ask the dude who had to check him in practice every day.

“He’s got so many ways now to score the ball. You never know what’s coming next,” says Karsten Tadda, a backup PG on the national team who first met a teenaged Schröder after he shred Tadda’s German pro league squad. “Normally the goal is only to stay in front of him. You don’t have any chance of stealing the ball with his long arms protecting the ball.

“When he’s going to the basket, it doesn’t matter who’s trying to block him at the rim. Nobody’s got a chance to block him,” Tadda continues. “I haven’t seen anyone block his shot on the national team or in our games. When he’s going to the basket, I’m like, Damn, it looks so easy.”

In Atlanta, Hawks coach Mike Budenholzer has noticed the same thing. “Dennis, I think at times he’s just determined to get to the paint, get to the rim,” says Bud.

Yeah, like the time last season against the Spurs when he got a step on Kawhi Leonard and pounded home a dunk over Tim Duncan.

“He just opens up the floor so much for all of us,” adds Hawks All-Star center Al Horford. “His speed, when he attacks the basket, he’s either going to get a layup or one of us is going to get an open look. There’s not a lot of guys that can blow by you like that.”

For the Hawks to get past the Celtics and take serious aim at dethroning the Cavaliers in the second round, they’ll need Schröder to have more nights like the one in DC. Or like Game 3 against Boston, when Schröder erupted for a career playoff-high 20 points off the bench and wasn’t afraid to mix it up with C’s All-Star Isaiah Thomas. The Hawks lost the game, though, and the series now shifts back to Atlanta tied at 2-2.

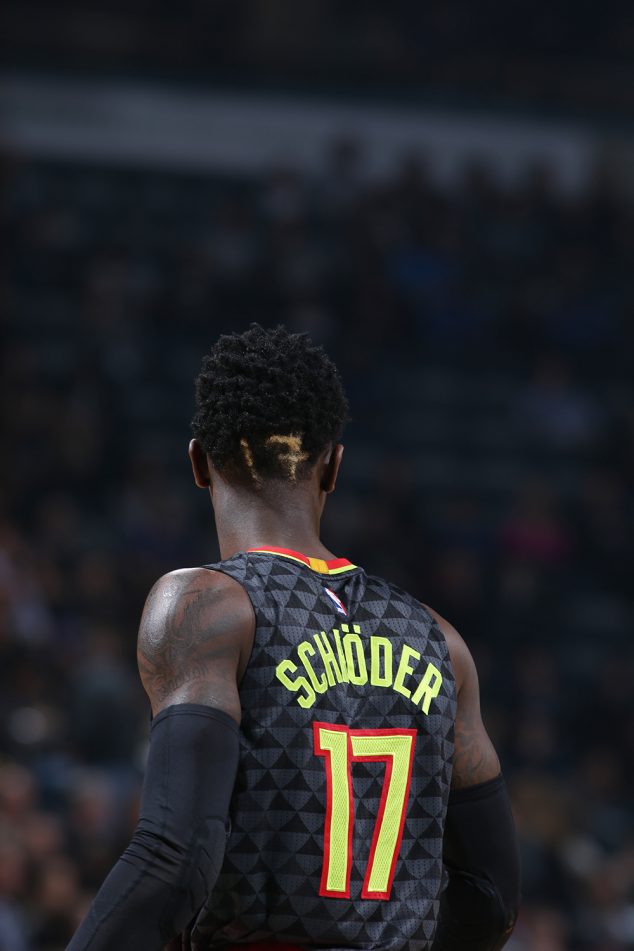

Schröder already has a strong following in the US because he’s tough (when he got a tooth knocked out during a game this season, he put it in his sock and kept playing), and because he’s cool (he dyed his jersey number into the back of his hair, as you can see above), and because he can flat-out play. Being “different,” as Horford describes him, is what sets him apart.

In Germany, basketball is far from the national sport, lagging behind soccer and more traditional Olympic sports. Even when it comes to hoops, he’s hardly Dirk-level yet, but his star is rising. He landed a spread in GQ and the cover of NBA 2K16 in Germany, and Tadda says he had to pick Schröder in the first round of the fantasy basketball league he plays in with his German league teammates, just to make sure to get him.

“They said he would never be a good point guard, he would never be able to play for the national team, he would never lead a team—those were all comments that he had to face early in his career,” says Okulaja. “I think he is very happy now that all those people who criticized him and said he would never amount to anything, all of those guys are very quiet now.”

—

Abe Schwadron is an Associate Editor at SLAM. Follow him on Twitter @abe_squad. Photos via Getty Images